Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 31min

Within the first ten minutes of Wild Strawberries, a surreal nightmare unfolds in the mind of Professor Isak Borg, prompting a sudden shift in his travel plans. The empty city streets he anxiously wanders are blown out in high-contrast monochrome, blinding us with the glare of white pavement and dissolving shadows into inky voids. A clock without hands marks the timelessness of this dream space, but also warns of Isak’s own impending death. Time is running out. A man with a seemingly painted-on, scrunched-up face melts into a dark liquid, and a driverless carriage led by charcoal-coloured horses topples over, tossing a coffin out onto the road. Inside, Isak finds himself. He wakes with terror, and a mysterious new resolution – he will not take a plane to the ceremony where he will be receiving the honorary degree of Doctor Jubilaris that evening. Instead he will drive, and with his daughter-in-law Marianne in tow, he sets out on a physical and spiritual journey of self-reckoning.

This existential search for life’s answers makes for a fascinating companion piece to the other Ingmar Bergman film that came out in 1957, The Seventh Seal, with both marking a new trajectory in his career towards more philosophically minded films. Their combined success also venerated him internationally as a filmmaker not to be underestimated, and there may even be a passing of the torch here from one acclaimed Swedish director to another in his casting of Victor Sjöström. Though Bergman had previously used him in To Joy as a supporting character, he is front and centre here as the elderly physician facing up to his troubled past and unsettling future, reflecting on them with sorrowful dissatisfaction. Despite his professional achievements, Isak is a man who has steadily distanced himself from those he once held dearest, and over the course of this road trip each arrive back into his life in the most unexpected ways.

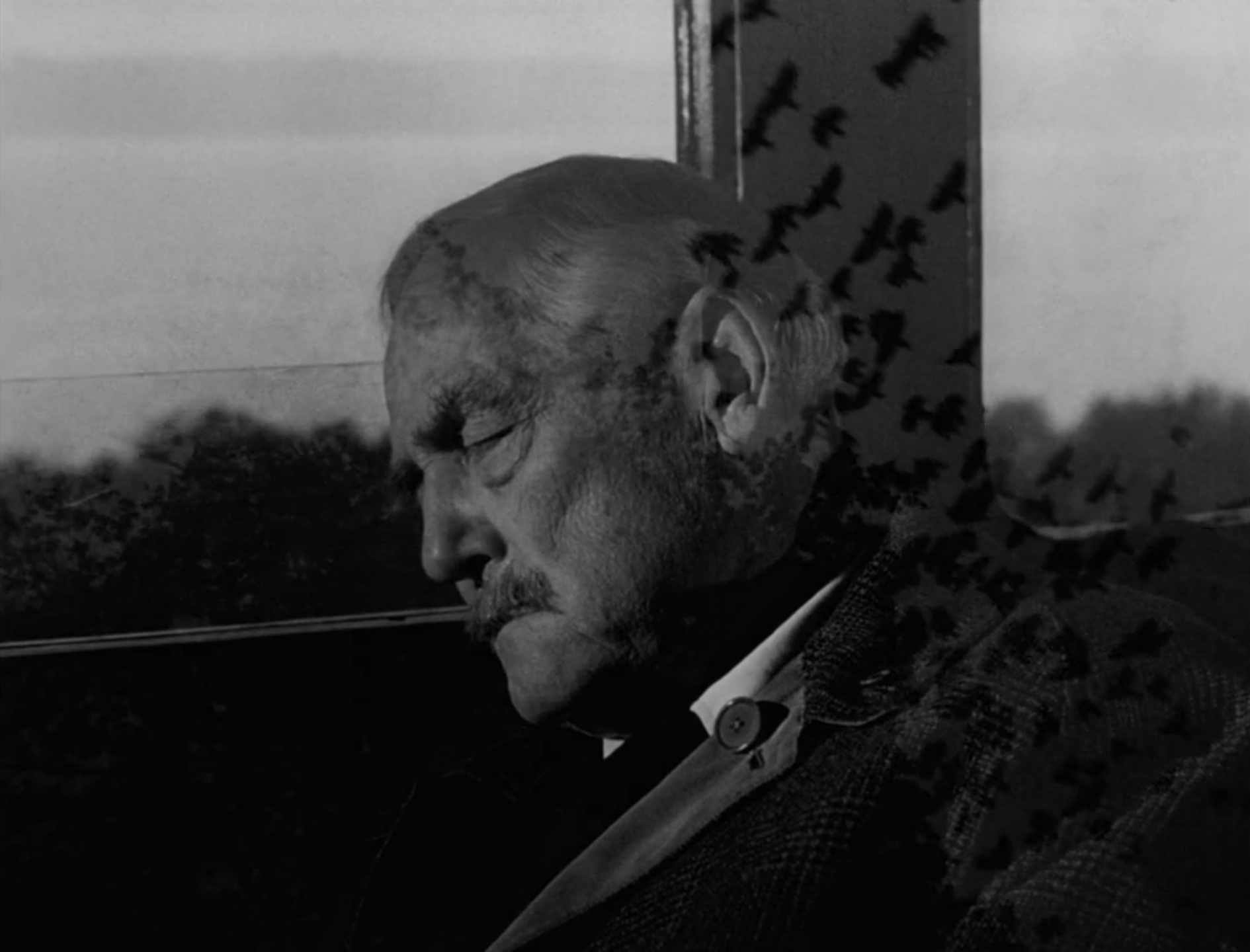

This predominantly takes place through the bleeding together of dreams, memories, and symbols, drifting by on the powerful current of Bergman’s poetic screenplay. “The day’s clear reality dissolved into the even clearer images of memory that appeared before my eyes with the strength of a true stream of events,” Isak eloquently contemplates, as Bergman quite literally dissolves the barriers between his material and psychological worlds via his graceful scene transitions. When the professor rests against the car window and considers “something overpowering in these dreams that bored relentlessly into my mind,” his voiceover is visualised with a slow fade into the past, sending a murder of crows flying across his sleeping head.

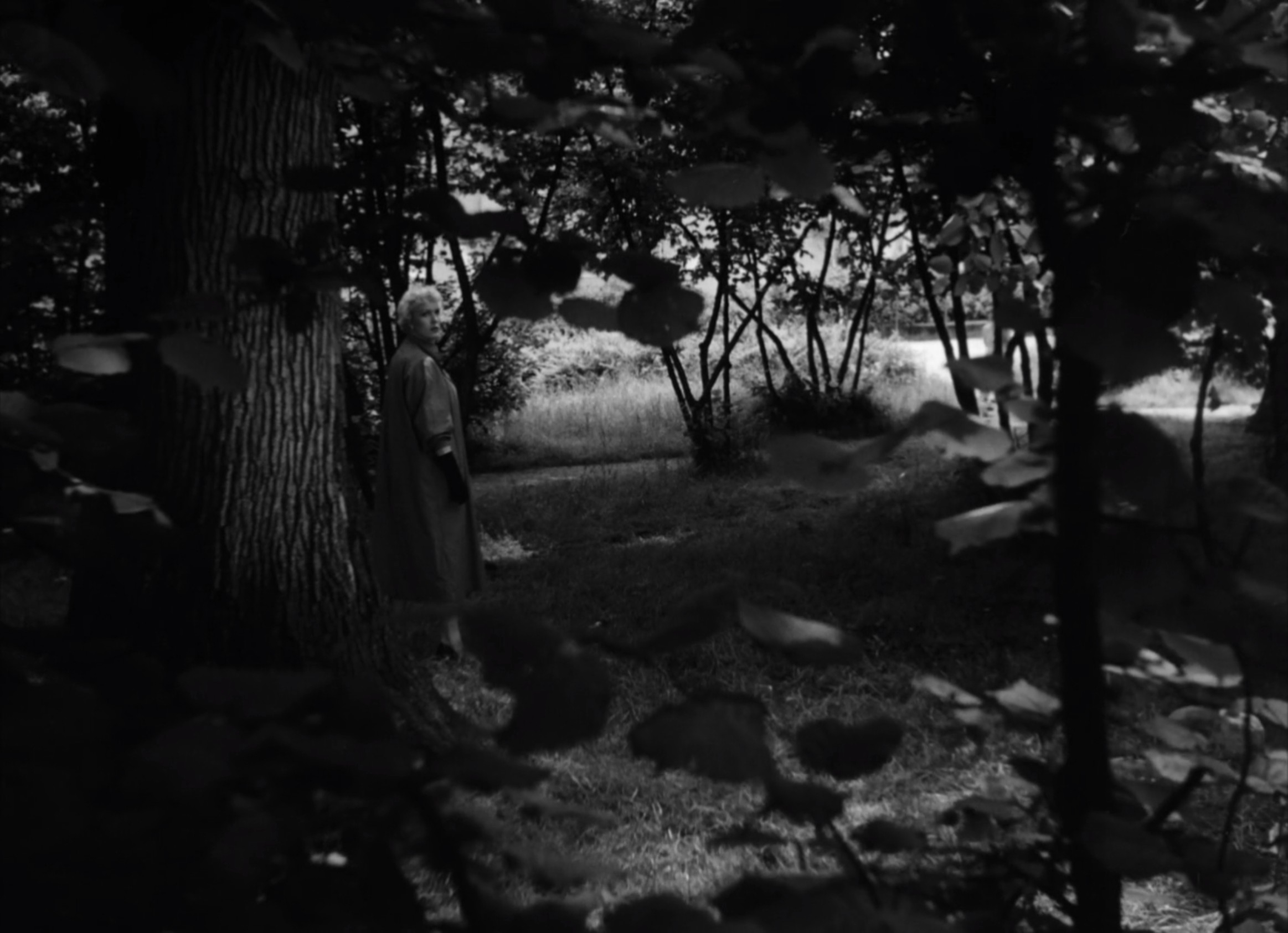

It is especially his visit to the summer house he visited throughout the first twenty years of his life that opens the floodgates of nostalgia, playing out his romance with the beautiful Sara who would eventually marry his brother, Sigfrid. While everyone else around Isak in these flashbacks is young, Sjöström continues to play Isak as his older self, fully inhabiting his own memories. As his white-clad peers gather and pray around a table in preparation for dinner, Bergman’s camera tracks forward into the room through a dark doorframe, and Sjöström lingers shamefully on the shadowy edges in his black attire, clearly set apart from these days of romantic idealism. In the present, Isak can’t help but draw comparisons between his old sweetheart and a hitchhiker similarly named Sara – and apparently neither can we, given that both iterations are flanked by rivalling suitors and played by frequent Bergman collaborator Bibi Andersson.

She isn’t the only modern surrogate calling back to Isak’s past either. When he picks up Sten and Berit, a married couple with a broken-down car, their mutual resentment reminds him of his own relationship with his late wife. It is a miracle that Bergman’s early scenes of Isak and Marianne alone in the front seat are so visually engaging with their piercing deep focus, but it is when he fills the car to the brim that the genius of his blocking is truly revealed, forming layered representations of Isak’s past and present. Right in the back we find Sara and her two men, calling back to his adolescence. In the middle seats, Sten and Berit’s bickering continues to fill him with raw regret over his marriage, and leaves everyone else to sit in awkward silence. And there in the front driver’s seat right by his side is Marianne, his sole connection to his estranged son, Evald.

Gunnar Björnstrand makes minimal appearances in this role, but there are definitive resemblances between his and Sjöström’s performances, both being cynical, irritable men who care little for their wives. Clearly the sins of the father have been passed onto the son and perhaps even amplified, as Evald is quick to cut down Marianne’s desire to bear children. “Yours is a hellish desire to live and to create life,” he heartlessly proclaims in her flashback, sitting in the exact same car seat that Isak is in now. “I was an unwanted child in a hellish marriage.” To look back at this family history from the other direction, it is clear that Isak may have inherited the same prickly attitude from his own parents too – specifically his mother, who Marianne describes as “cold as ice, more forbidding than death.” During his short visit to her along the road trip, she hands him the gold watch that his father used to own, which in a disturbing turn of events is revealed to not have any hands much like those of his dream.

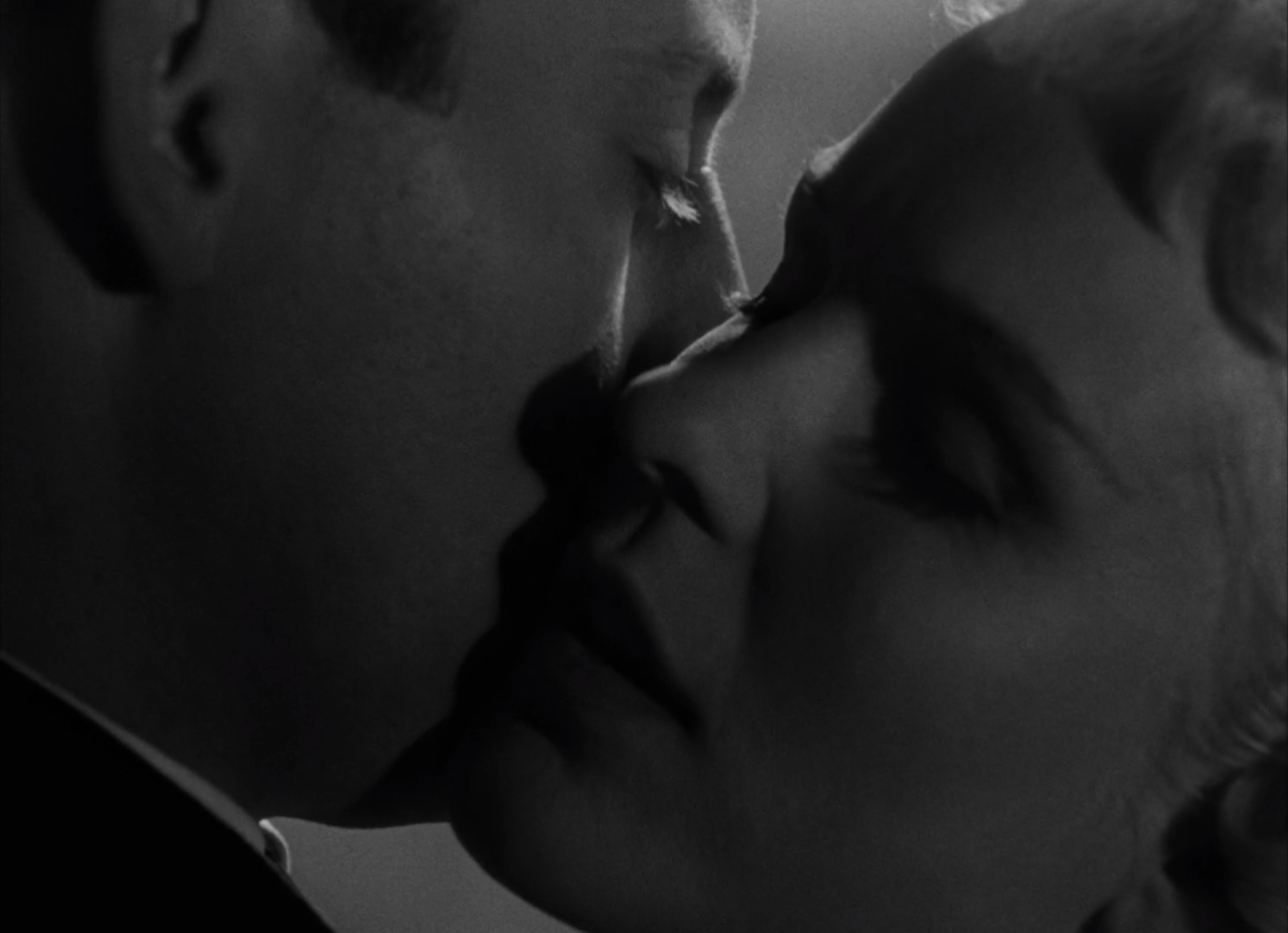

Bergman had certainly dabbled in magical realism before, but surrealism as concentrated as this is new for him in 1957, penetrating the depths of his protagonist’s mind in such ways that can only be felt via absurd, impressionistic imagery. In a law court preside over by the quarrelling husband Sten, Isak is forced to read nonsense on a blackboard that he is informed translates to “A doctor’s first duty is to ask for forgiveness.” He stands charged of being incompetent, as well as many minor offences including “callousness, selfishness, ruthlessness,” each brought against him by his wife who is deceased in the reality, yet lives on in his mind. A rippling reflection in a dark pond bridges one dream world to the next, where he finds a memory of his wife carrying out an affair in the forest, and contemplating his impassive reaction back home when she eventually tells him of her infidelity. Soon, she and her consort disappear without a trace, and Sten becomes a dark reflection of Isak’s subconscious, considering the doctor’s meticulous method of emotional detachment.

“Gone. All are gone. Removed by an operation, Professor. A surgical masterpiece. No pain. Nothing that bleeds or trembles. How silent it is. A perfect achievement in its way, Professor.”

Perhaps he would have found more satisfaction in the university’s ostentatious ceremony the previous day, but now as he accepts his certificate and listens to speeches, there is a strange emptiness to the routine proceedings. Is this the legacy he has made for himself?

With his manifestations of old memories in his current reality though also comes second chances for all those still alive. “I can’t live without her,” Evald confesses to his father, resolutely deciding to stay by Marianne’s side through the birth of their child. Through his newfound appreciation of his daughter-in-law, he also uncovers the dormant love for his own wife that he never showed during her life. Such are the power of dreams in Wild Strawberries, mulling through decades of nostalgic and shameful memories to reveal greater truths about oneself. By turning Isak’s car into the vessel through which he navigates such fantasies too, Bergman grounds them all in a robust visual metaphor. As the elderly professor now drifts off to sleep though, his face is not tormented by dark musings, but lightened by a gentle peace. “If I have been worried or sad during the day, it often calms me to recall childhood memories,” his mind echoes, before finally slipping away into worlds untouched by bitterness and regret.

Wild Strawberries is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes.