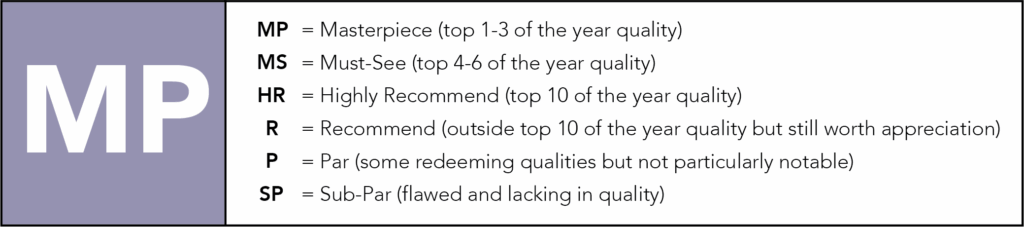

Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 48min

The cycles of life in Yasujirō Ozu’s domestic dramas are as natural as seasonal changes, and just as inevitable. Parents grow old, children move out of home, and their youthful innocence matures into a worldly wisdom which guides them into new experiences. This is the transitory period that he represents in the title Late Spring, where the youth of 27-year-old Noriko comes to an end, though Chishū Ryū’s gently spoken widower Shukichi is not the obstacle to his daughter’s inevitable departure. As Noriko holds tight to her ageing father, it is rather her reservations about marriage which create friction in their household, pensively reflecting the evolving responsibilities of mid-century Japanese women in their families and society at large.

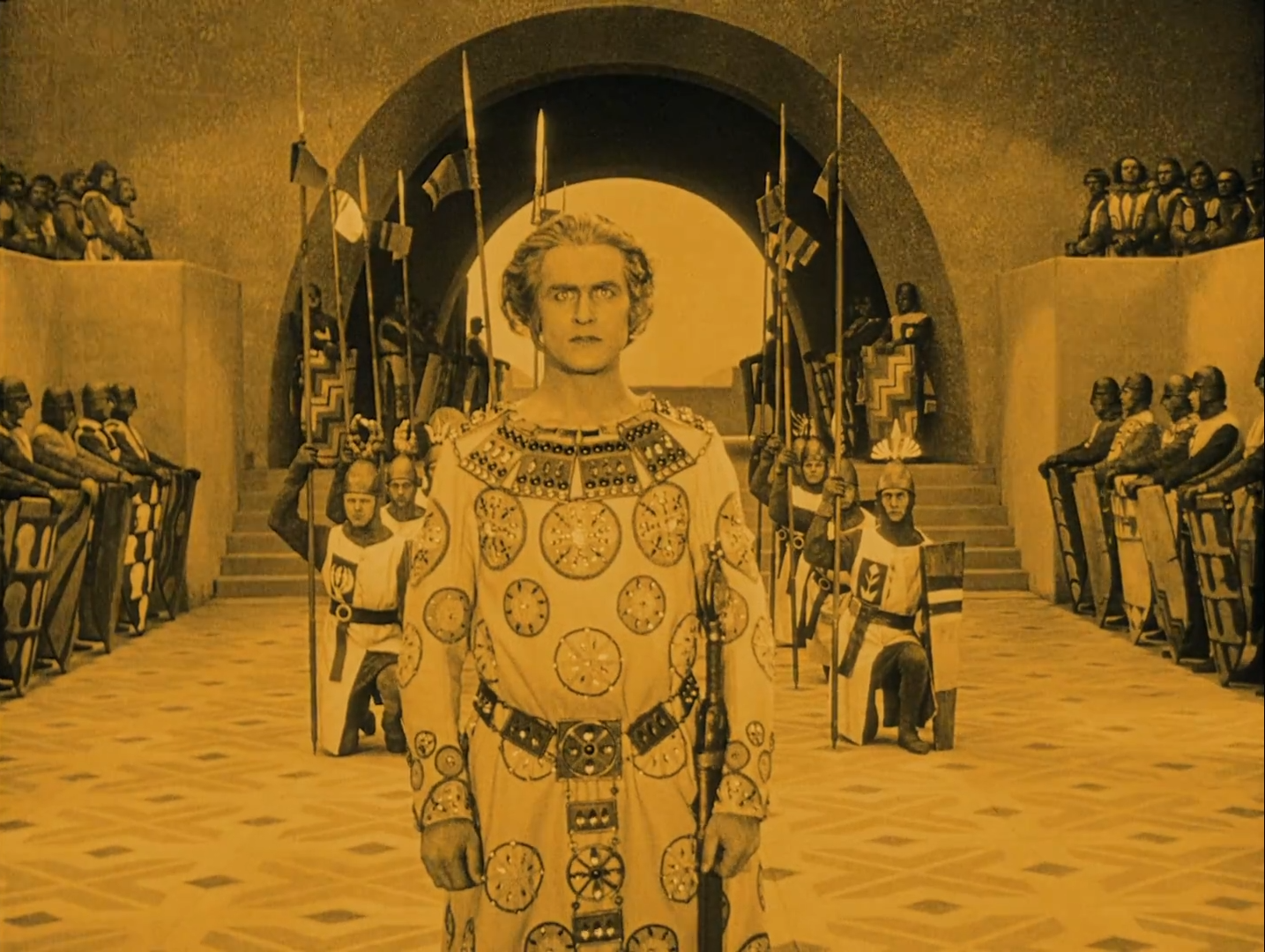

Setsuko Hara is radiant here in her first of many fruitful collaborations with Ozu, becoming the emotional centre around which his mise-en-scène and narrative layers delicately form. Her perpetual, beaming smile draws our focus in wide and mid-shots alike, and even continues through her savage digs at the remarriage of her father’s friend Onodera, somewhat amusingly labelling the act “filthy” and “indecent” without so much as a scowl crossing her face.

From Noriko’s perspective, building a new life outside of her current home would be a selfish act, with even the mere thought threatening to undermine the security she finds in caring for her father. As far as she is concerned, “Marriage is life’s graveyard” – or at least, those are the words her divorced friend Aya puts in her mouth. The moment that Aunt Masa starts pushing her strongly in this direction by suggesting that her father is planning to remarry their widowed neighbour Mrs. Miwa, Hara’s magnetic smile is wiped from her face, and it is quite some time before we see it return.

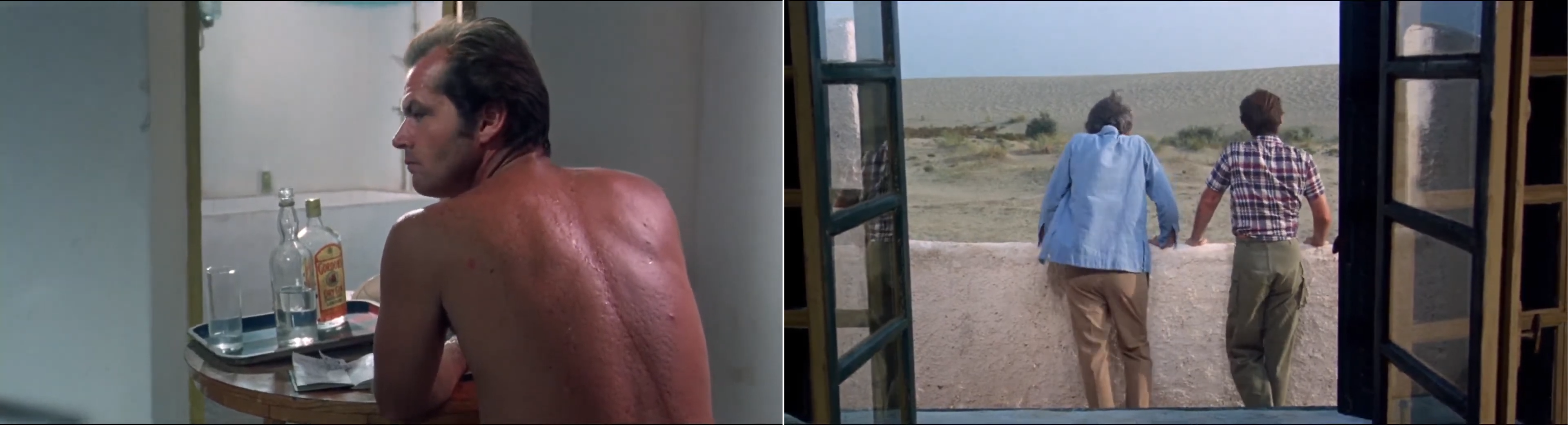

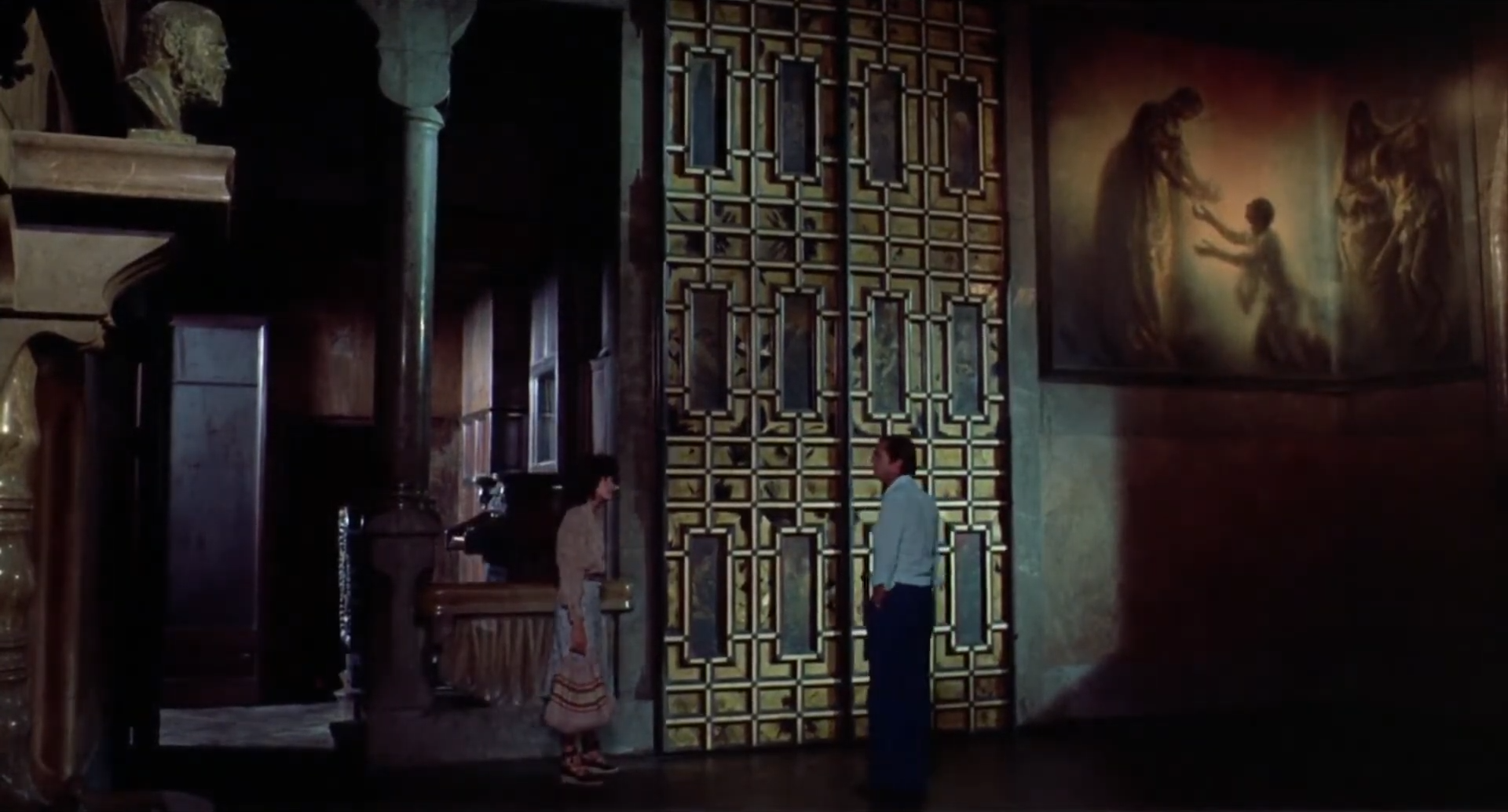

Indeed, Ozu’s thoughtful blocking of Noriko in his open doorways, corridors, and shoji screens essentially constructs a protective shell around her, connecting the young woman to the monotonous minutia of her family home. He designs his compositions through parallel and transversal lines, geometrically splitting the frame into segments that give structure to the organic, and beauty to the mundane. Here, he develops a formally rigorous aesthetic which would extend to the end of his career, representing every book, chair, and hanging garment as an extension of his characters.

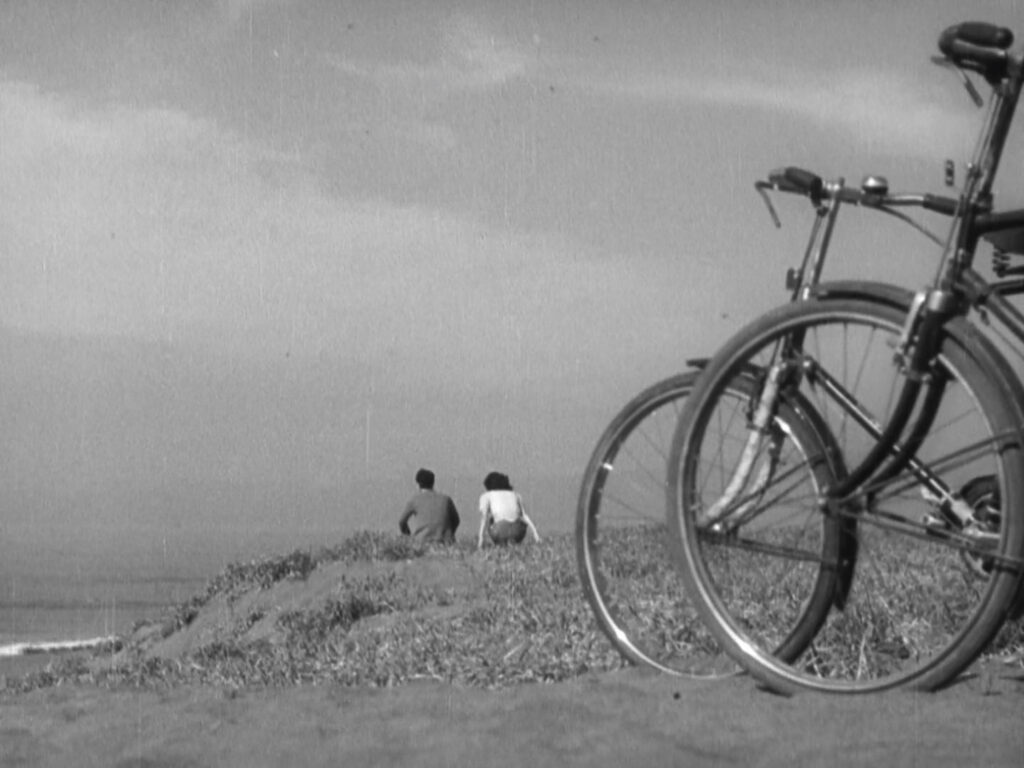

Through Ozu’s consistently low angles too, there is also an extraordinary humility baked into this perspective. The seconds before an actor enters a room and after they exit are spent in quiet reflection, finding traces of life that exist beyond drama, and embodying their gentle presence by what remains behind – a pair of sitting cushions, a coat hanging on a rack, and a hat resting on a briefcase for instance, collectively break up the living room’s harsh angles with hints of humanity. When Noriko cycles with her engaged friend Hattori, this pattern continues in his framing of their parallel bikes, parked in the foreground while mirroring their tender pairing in the distance. There may not be any romance shared between them, yet this does not devalue their connection in Ozu’s eyes, earning the greatest honour he could bestow upon any relationship – a beautiful, elegant composition.

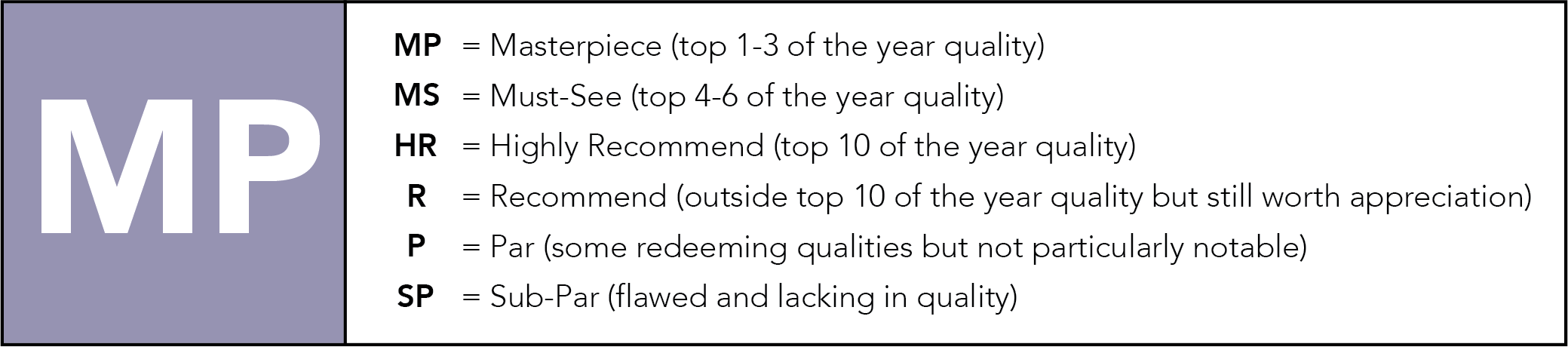

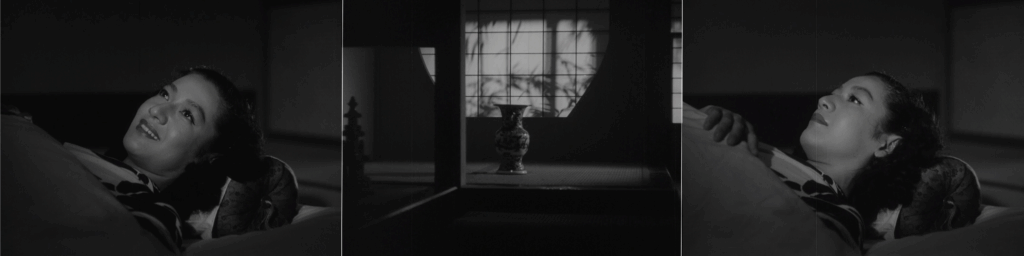

At its most enigmatic, Ozu’s dedication to still life artistry stirs something deep and inexplicable in our souls too, mystifying generations of film scholars who would pick apart the meaning of a simple vase. This shot in question is specifically a cutaway during Noriko and her father’s overnight stay in an inn, wedged between two close-ups of the young woman’s face as she silently comes to terms with their inevitable separation. Given that Noriko’s eyeline is aimed towards the ceiling, it is notably not a point-of-view shot, so we are left to surmise that the perspective we are being given is solely Ozu’s. In this context, perhaps what the vase symbolises is less important than its formal function, acting like a comma halfway through a sentence. As such, the cutaway emphasises the crucial difference between the pair of close-ups it separates – that bright, radiant smile, completely disappeared when we return a few seconds later.

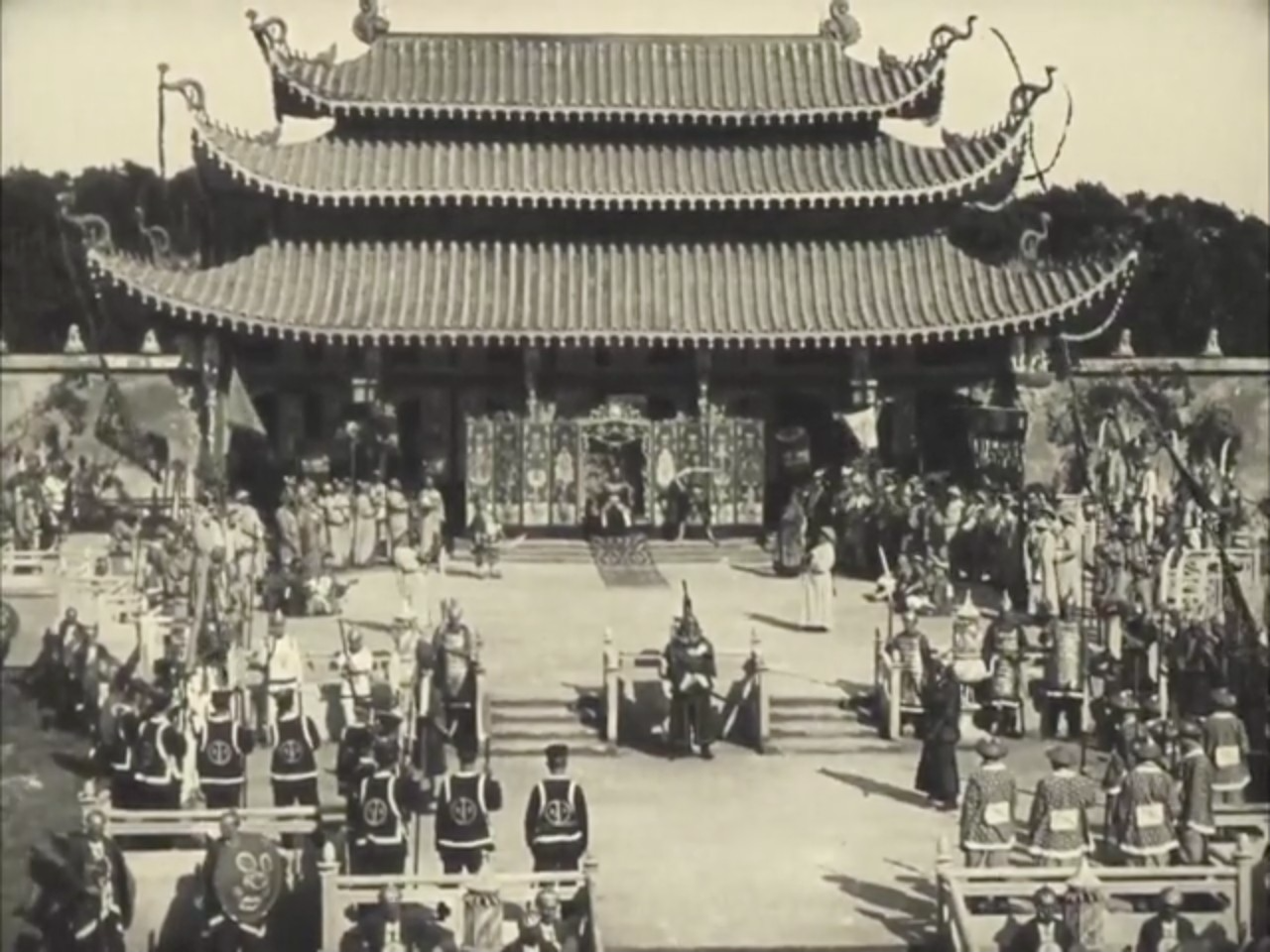

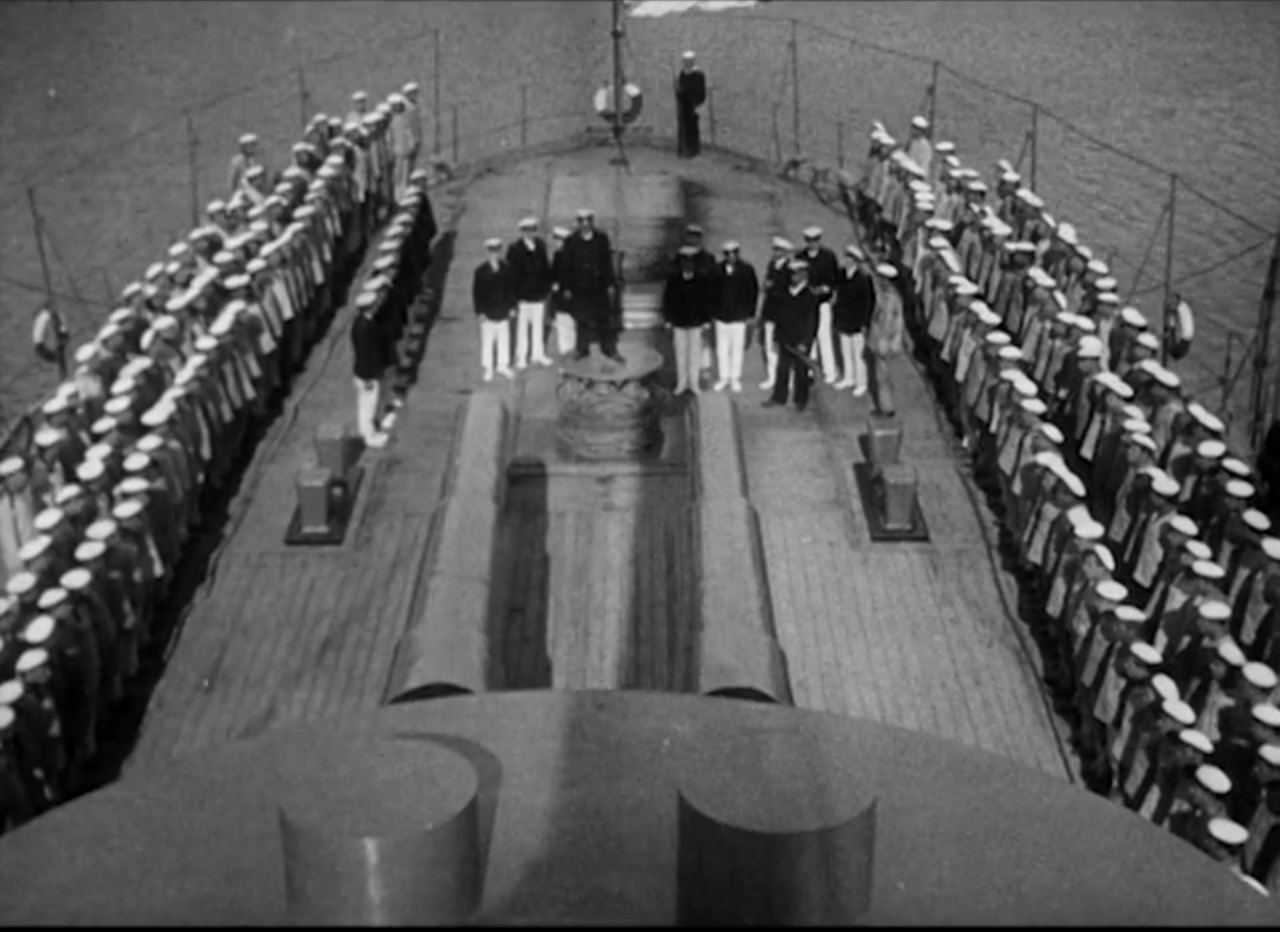

No words are needed to express the insecurity that Noriko feels around the prospect of her father remarrying, especially with Ozu using the backdrop of a Noh performance to underscore their exchanged glances across the audience with Mrs. Miwa. His editing is in tune with her distracted mind, following her father’s lead with a friendly nod and smile to their neighbour, before her expression drops into sullen sorrow. “The iris hedge planted next to our old home, only the colour remains as it was back then,” the Noh singers drone in long, slow verses, wistfully reflecting on that ephemeral past which slips from Noriko’s grasp and is replaced by a newfound wisdom. “All the earth will be enlightened, even the flowers and the trees,” they conclude as Ozu cuts to a low angle of tree branches spreading out across the sky, connecting her spiritual journey to the very earth itself.

Nevertheless, Ozu’s Japan remains a land of quiet conflict between nature and civilisation. As we watch his transient pillow shots unfold, we often question if these ancient pagodas, commercial train lines, and modern interiors stand alone as observances of an evolving post-war society, or whether they are functional establishing shots announcing the location of the next scene. We are effectively led to consider both with equal significance, sensitising us to the intricacies of Noriko’s world that boldly strives for the future, yet which paradoxically holds onto its nostalgic heritage. It is consequently easy to empathise with both sides of Late Spring’s core conflict, though as Noriko finds herself falling for the man she has been set up with, Ozu’s visual harmonies develop a strange, distinctive melancholy.

The pillow shots step up in frequency here, floating along lyrical meditations of the fate that has befallen this engaged woman, and the lonely father who now mourns the void left in his home – not that he would ever let that show. The notion that he would be remarrying was merely a lie he constructed to nudge her along without feelings of guilt, and now as her bittersweet departure arrives, he gifts her his own words of wisdom.

“Happiness isn’t something you wait around for. It’s something you create yourself. Getting married isn’t happiness. Happiness lies in the forging of a new life shared together. It may take a year or two, maybe even five or ten. Happiness comes only through effort. Only then can you claim to be man and wife.”

Sitting alone in his darkened home, he slowly peels an apple, recognising that Noriko’s happiness is no longer his to hold onto. Chishu Ryū doesn’t need words to express such incredible sorrow either as he bows his head in resignation, gracefully submitting to those cycles of nature which Ozu manifests in one last cutaway to rolling waves upon a beach. With such thoughtful editing and curated imagery guiding Late Spring’s lyrical rhythms forward, there is both profound joy and sadness to be found in this father-daughter love – dominant for the years of one’s youth, though poignantly lacking the longevity of romantic, lifelong matrimony.

Late Spring is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.