Abel Ferrara | 1hr 49min

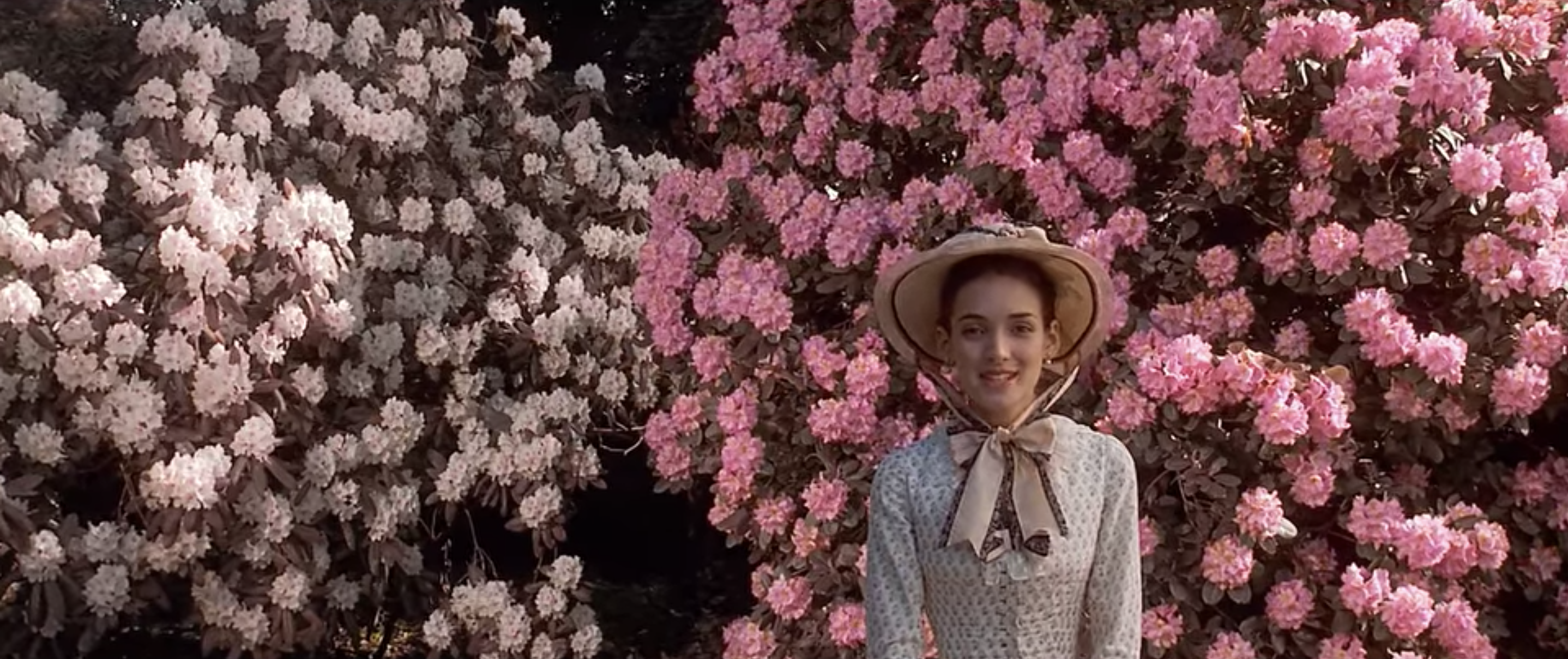

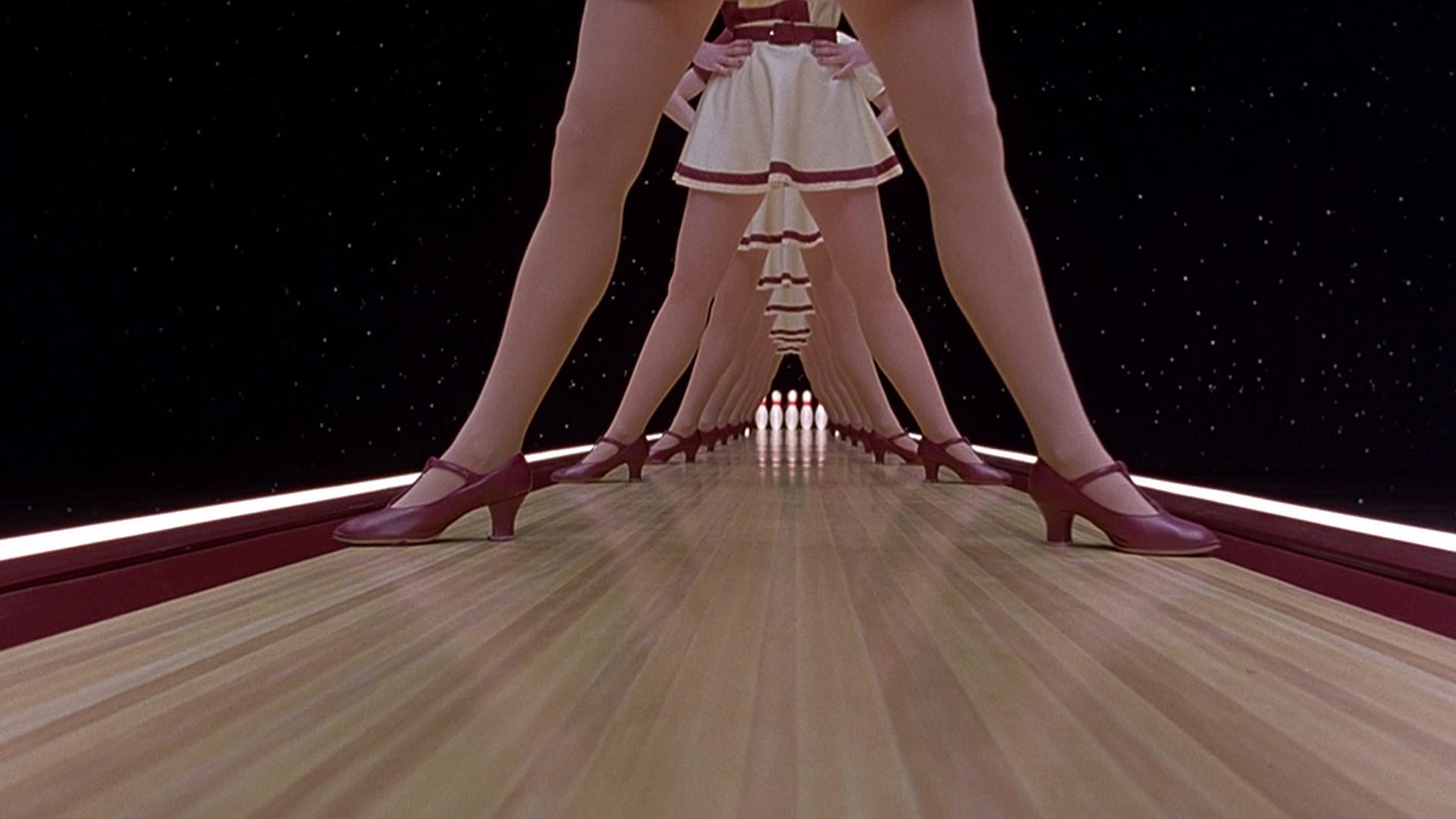

It is hard to tell at first how genuine drug lord Frank White is in his desire to “fix” New York, but we can at least gage that he is resolute in his ambitions. In his transition from prison back into society, a luxurious limousine is his ferry, and coinciding with this return is his second-hand assassination of past associates, evoking the climactic murders of The Godfather. Frank is our Michael Corleone figure here, though he evidently has far more years of experience in the criminal underworld behind him, commanding an aura of intimidation and respect in his imposing presence. As Christopher Walken stares out the window of the limousine with a stoic gaze, the radiance of passing street lamps fade up and down upon his face, and immediately Abel Ferrara brings us into King of New York with a deep, fearful reverence for this man.

There is also something so solemn and poignant about Walken’s eyes that speaks volumes about Frank’s love of the city. As he admires its beautiful lights and architecture from afar, we begin to believe that his motivations might go beyond mere selfishness. Perhaps it was those years he spent behind bars that has made him reconsider his own place in the world, as he searches for ways that he can contribute something positive, eventually latching onto a struggling children’s hospital in desperate need of private assistance. Still, it is difficult to remove the man from his ego, as it is in these aspirations that he also misguidedly sets his sights on becoming the Mayor of New York, viewing the office as his chance at some vague sort of redemption.

“If I can have a year or two, I’ll make something good. I’ll do something.”

The gritty realism of Ferrara’s location shooting in real New York streets and hotels is a perfect fit for this character study of urban grit and power plays, with The French Connection especially coming to mind in the use of this imposing city as a set for the thrilling cops-and-criminals battle at its centre. The authenticity of Ferrara’s style especially takes hold in his dim lighting, gorgeously diffused through the smog and mist of dark exteriors, and in one pivotal club shootout, drenching the room with a dark blue neon glow. A diegetic hip-hop track underscores the slow-motion deaths of criminals and police officers here, until eventually it spills out into the streets in a high-speed car chase.

It is within this extended sequence of moving the violence from one location to the next that King of New York reaches its stylistic apex. As Ferrara’s heavy rain beats down upon cars speeding down wet roads and their headlights beam through the deluge, the combination of his lighting and weather elements effectively heighten the dramatic stakes of this spectacular set piece. Eventually this loud, bombastic showdown turns into a cat-and-mouse contest of stealth and reflexes, with the few straggling survivors from both sides seeking refuge from the rain in a fenced-off construction site beneath a bridge. As it continues to pour down buckets in the background, Ferrara brings a visual texture to the muddiness of this confrontation, pulling both sides of the law into a dark, drab underworld of corruption and bloodshed.

Though we spend more time with Frank and his associates than the police officers, it is hard not to feel some sympathy for both. The antagonism they hold towards each other is devastating, obliterating each other’s dreams in a feud of mutual destruction. It is this hopelessness which settles in Frank’s minds in his last moments as he is faced with two options, both of which he realises will ultimately lead to the same result. Bleeding out in the back of a taxi with swarms of cops closing in, he could choose in this moment to go out fighting. But with his hopes of bringing something positive to the world dashed, perhaps it is his love for New York that holds him back from wreaking further destruction, recognising that a quiet exit might be the best thing he could really do for it. Really, Frank was never going to be the one to reform this city. It is rather in Ferrara’s skilful twisting of a traditional redemption arc that we see the true tragedy of this man bound by choices he made long ago, and who only is only willing to accept his true purpose when it is his turn to join the list of people killed in his name.

King of New York is not currently available to stream in Australia.