Brian de Palma | 1hr 38min

Adolescence is a painfully awkward time for the best of us, magnifying every embarrassing blunder under the scrutiny of unforgiving teenagers looking to distract from their own insecurities. We can barely understand the physiological changes taking place in our bodies, let alone our minds, rapidly transforming us into stronger, more complex versions of ourselves. As such, it is a lethal combination of hormones, repression, and psychological torment which bubbles up inside high school student Carrie White, who can barely catch a break between her bullies and fanatically religious mother. Coming of age is quite literally a horror show, so when those caught in the thick of it are belittled and terrorised, not everyone is going to make it out alive.

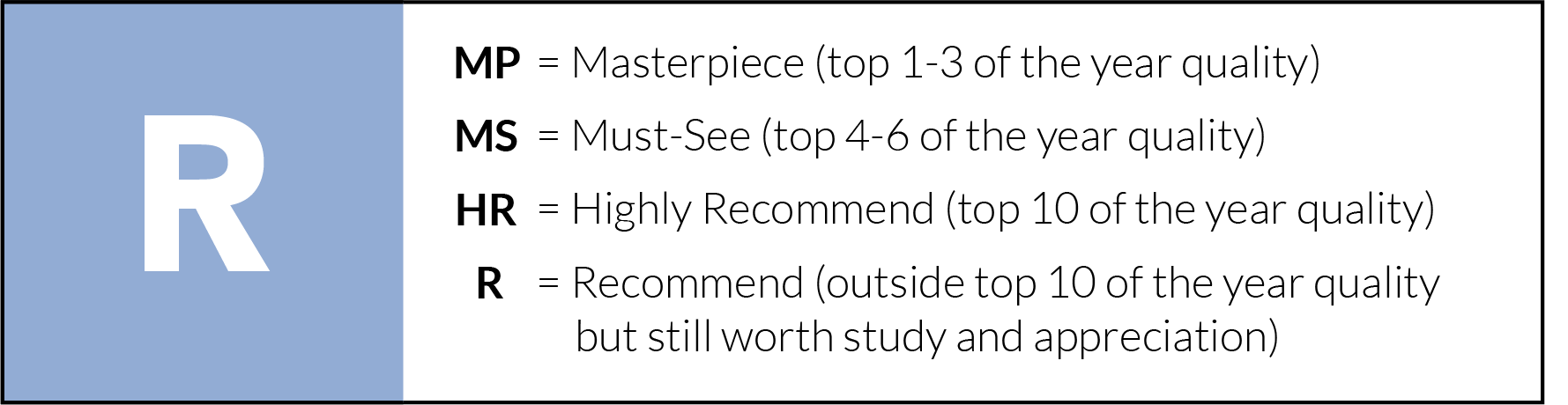

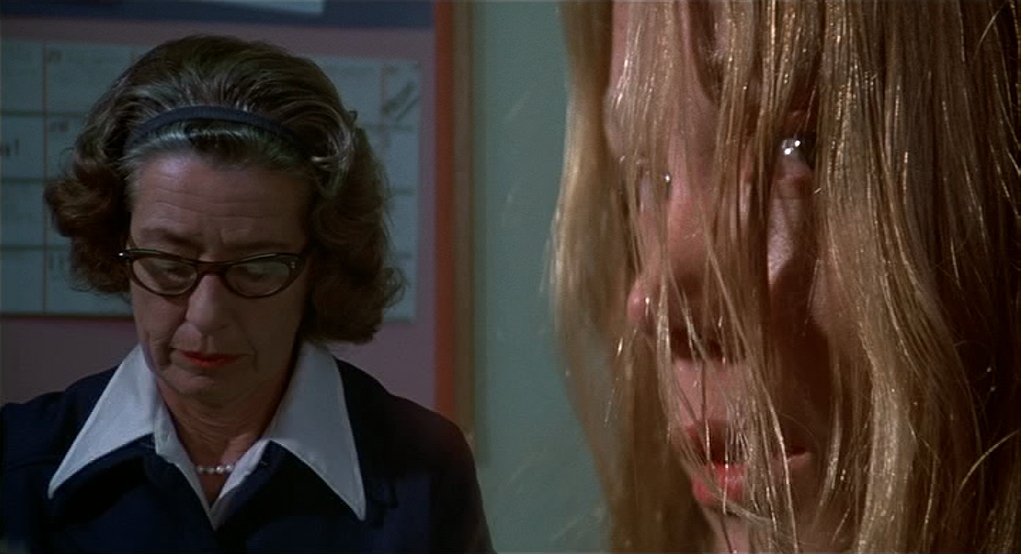

Our protagonist’s burgeoning supernatural powers are but a mere footnote in Carrie’s opening scene, though Brian de Palma does not treat the traumatic fallout around her first period with any less terror for it. Pino Donaggio’s piano, strings, and flute wring out a mournful melody as the camera floats in slow-motion through the fogged-up locker room where she showers, and close-ups linger on her bare skin as blood begins to cascade down her legs. “Plug it up!” the other girls viciously taunt as they throw tampons and towels at her, amused by her panic. Suddenly, a light bursts overhead, and Donaggio’s score recalls the stabbing strings from Psycho for the first of many times. De Palma may famously be characterised as the Hitchcock imitator, but clearly this influence extends to his pick of creative collaborators as well.

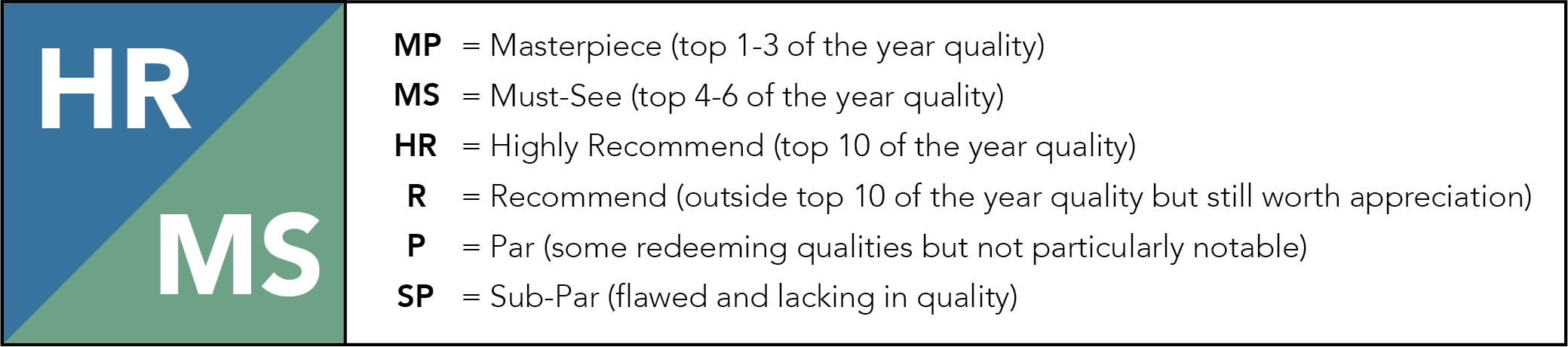

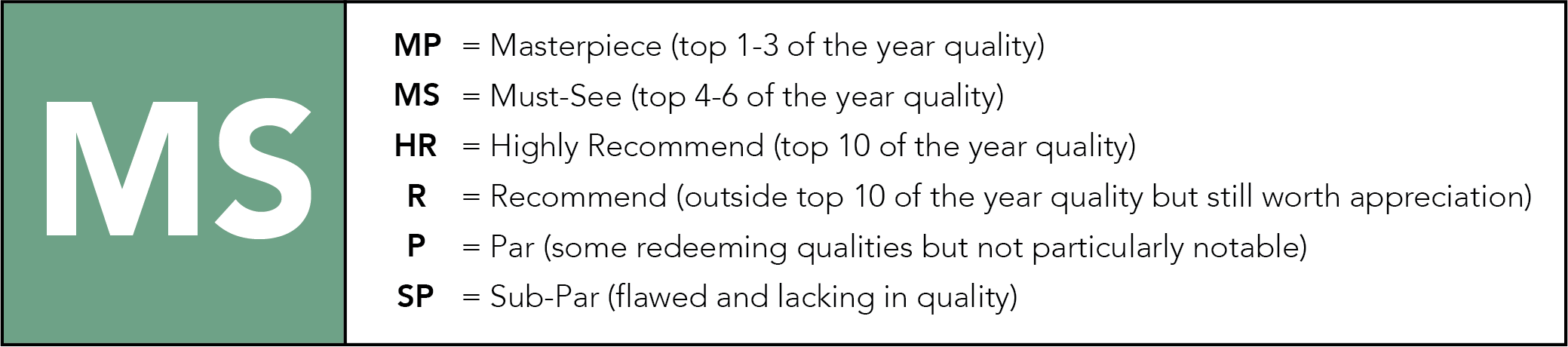

Carrie evidently finds no solace at home either. It was sin that brought on Carrie’s period, her mother chastises, refusing to educate her any further. To atone, she must be locked in the “prayer closet”, a claustrophobic space lit by a single candle and adorned with a grotesque, white-eyed icon of Saint Sebastian. Of course though, abuse does little to quell the dissent growing inside. Rather the opposite in fact, as her repressed anger continues to feed uncontrollable, telekinetic outbursts, vibrating an ash tray in the principal’s office and throwing a kid off his bike for calling her names.

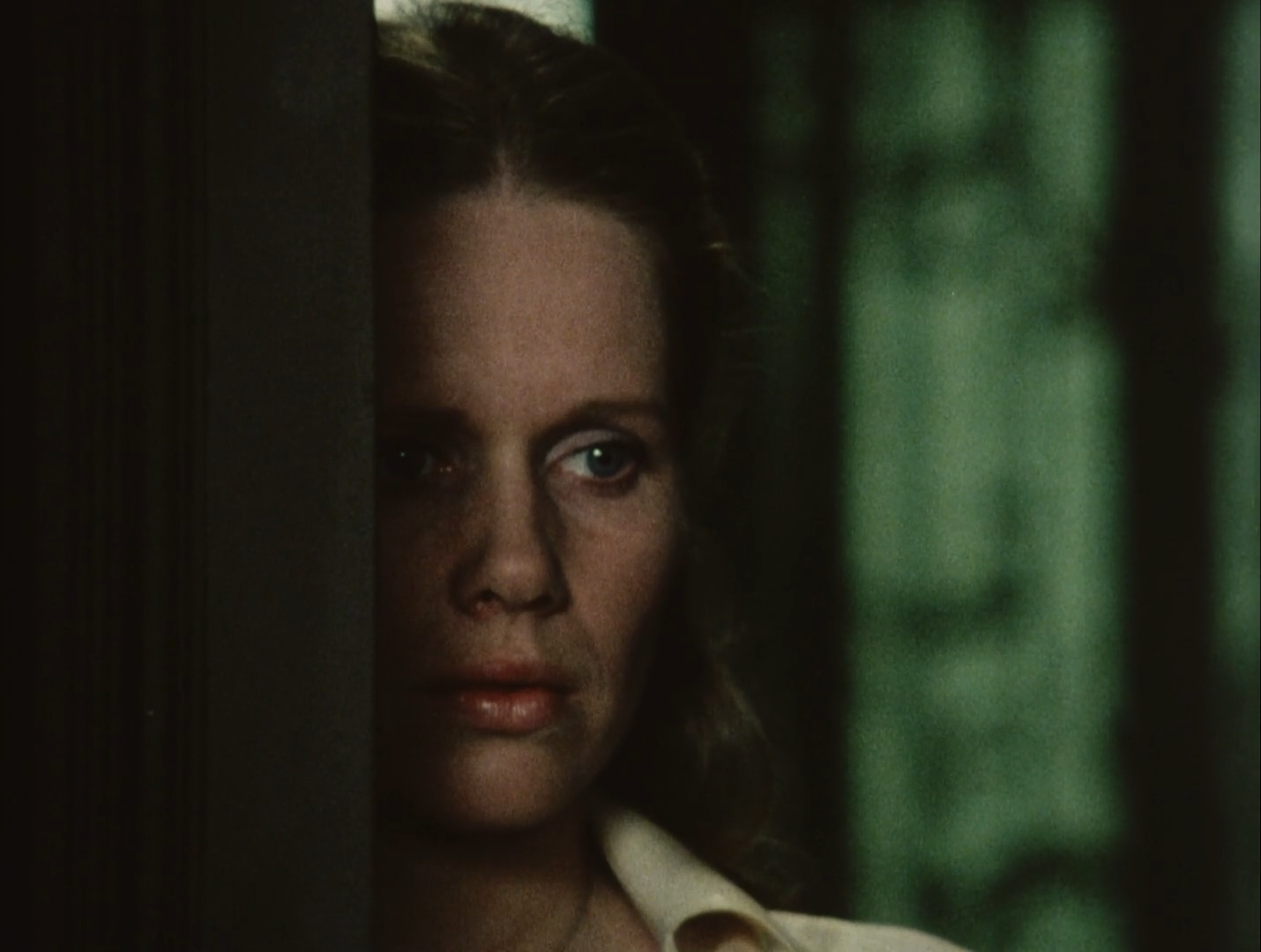

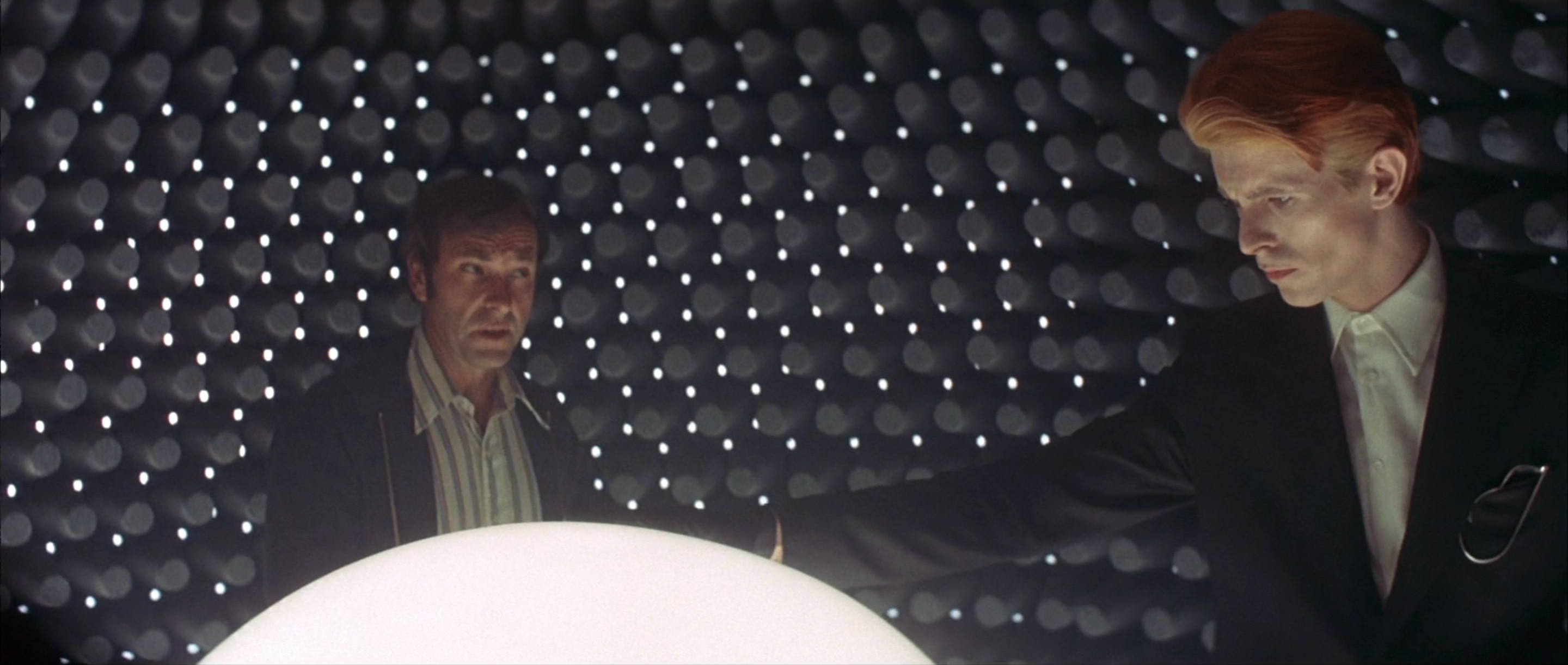

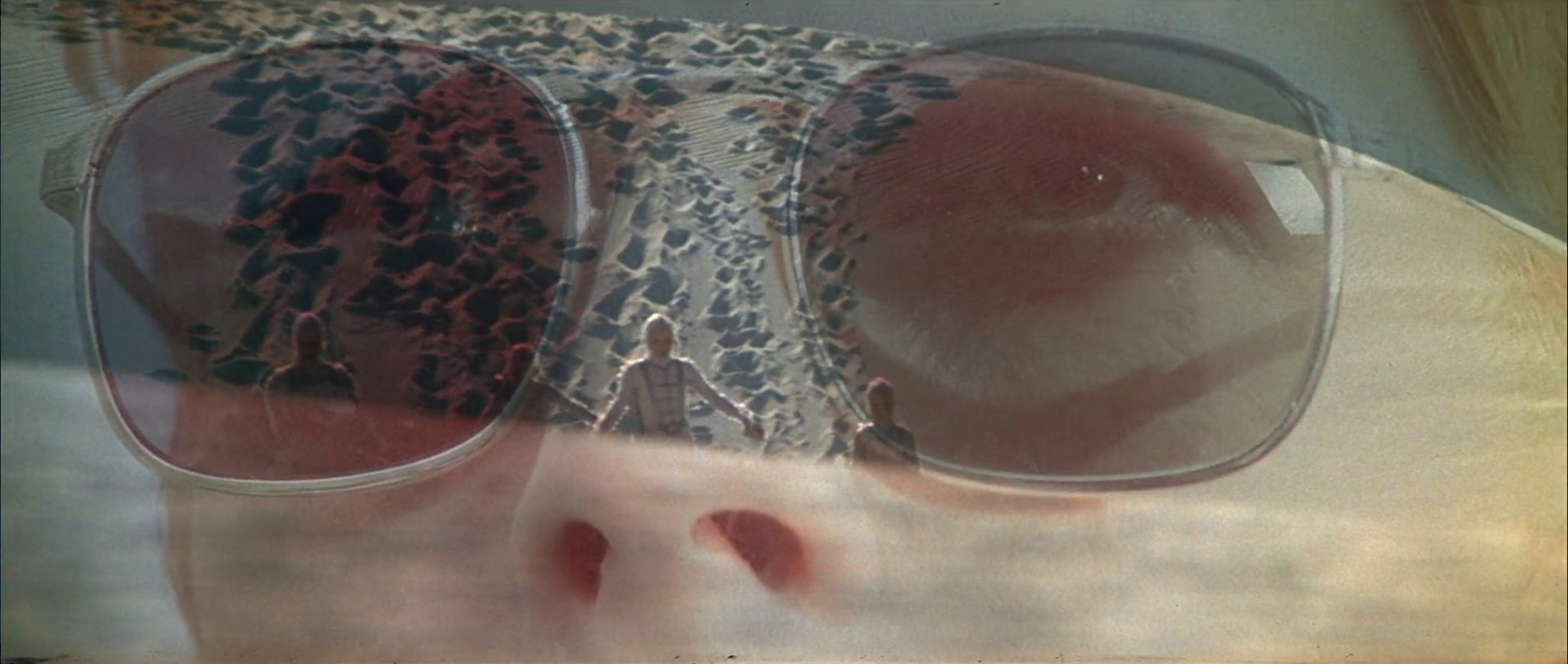

Even in these heated moments though, Sissy Spacek maintains a wounded vulnerability in her performance, revealing the shame and distress from which this teenager’s dark impulses emerge. She is isolated in de Palma’s blocking, yet through the deep focus of his split diopter lenses, intricate relationships are developed with the few characters who have some sympathy for her. Perhaps most prominent among these is fellow classmate Tommy, whose poem in English class draws mockery from everyone but her. “It’s beautiful,” she mutters under her breath, her face turned down in the background while his is pressed close to the lens in humiliation. With some encouragement from his girlfriend Sue as well, Tommy resolves to ask Carrie to the prom – and for a fleeting moment in her tragic life, her future starts to look bright.

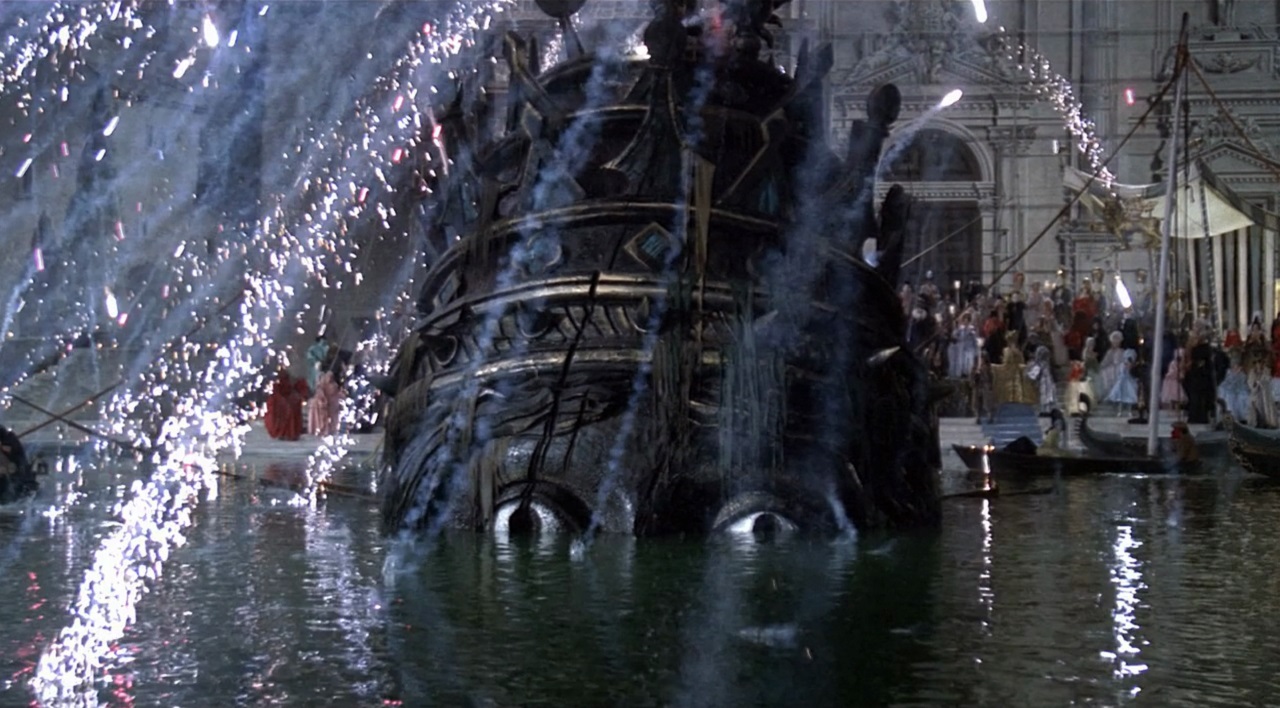

Not that her mother would ever understand the emotional and social needs of a lonely teenage girl. A thunderstorm rages outside as the two sit down to eat dinner on prom night, gloomily mirroring The Last Supper mural which looms behind them and foreshadows their own impending fates. Finally recognising her own power, she disregards her mother’s orders for the first time, pinning her to the bed and departing for what she is certain will be the happiest night of her life.

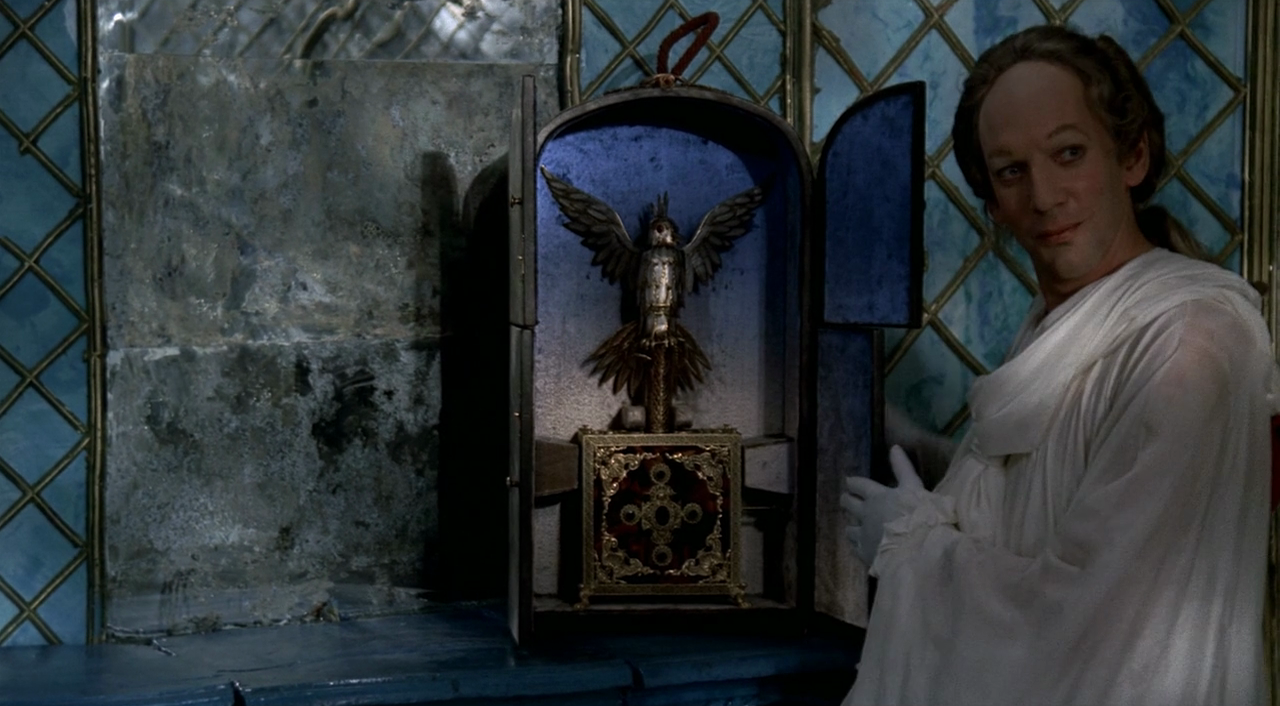

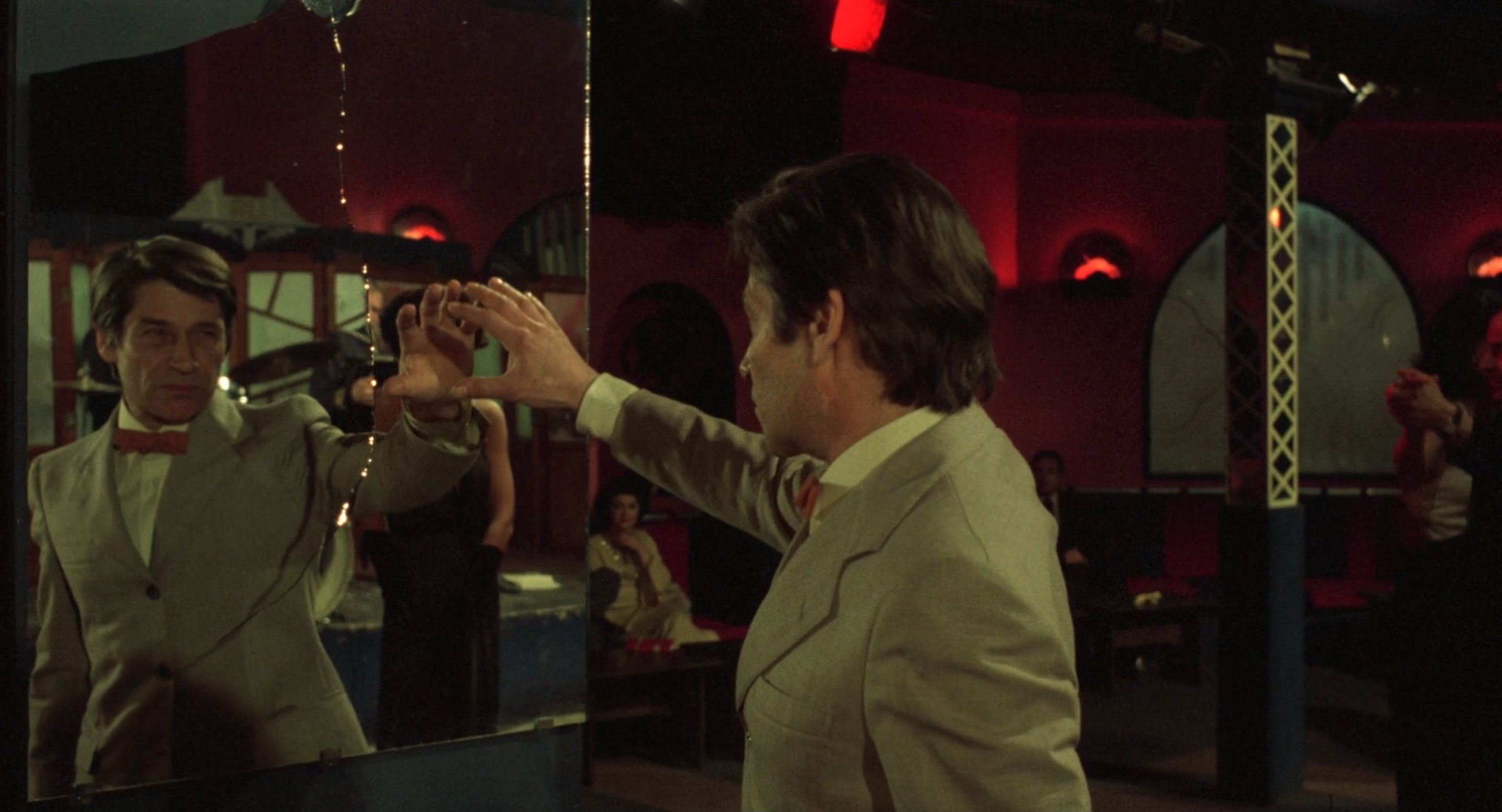

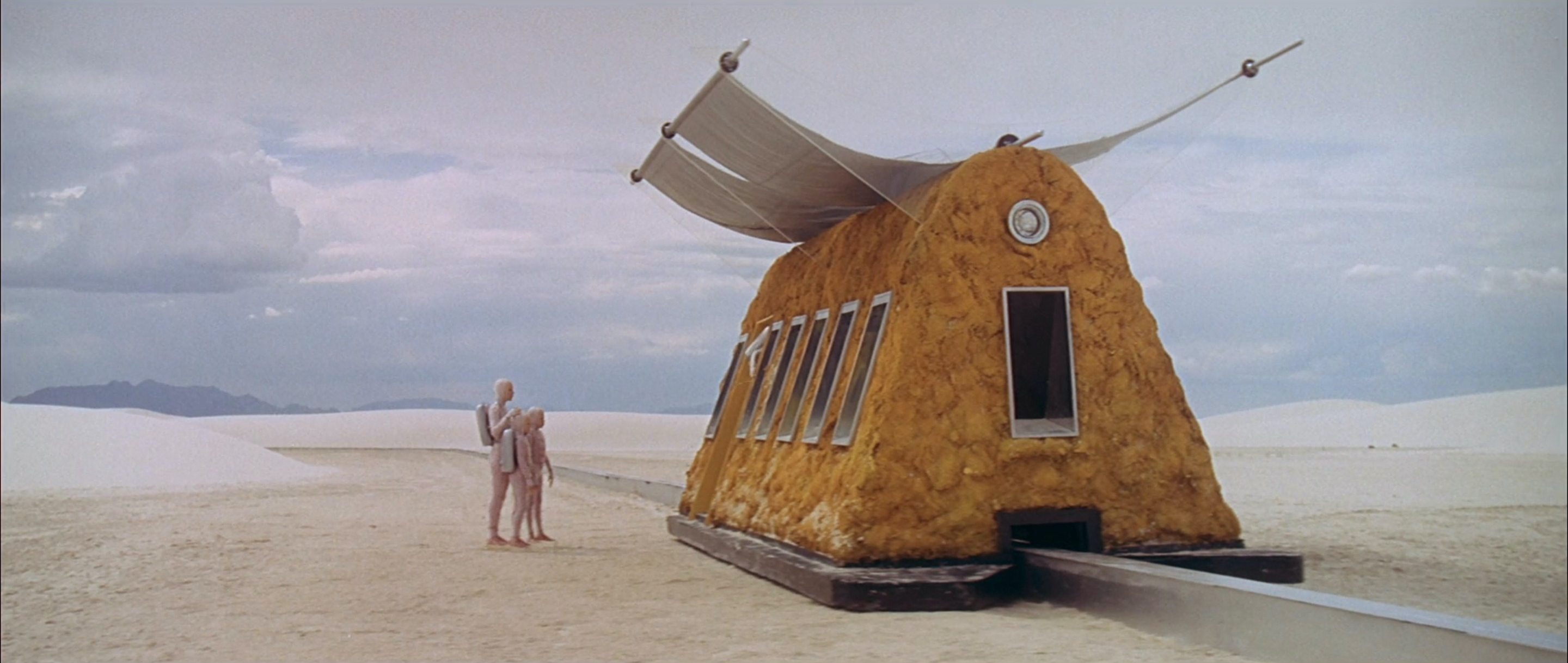

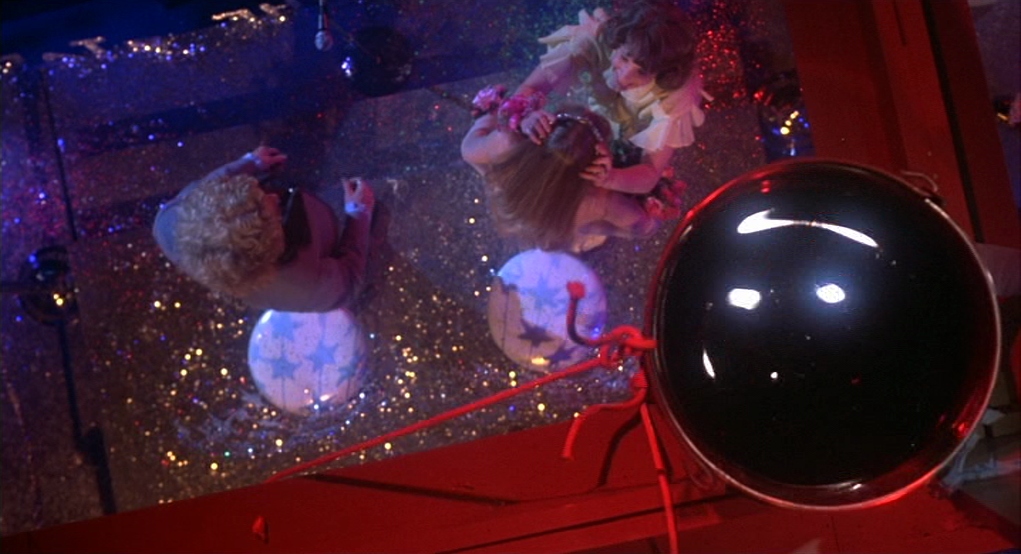

Right from the moment we enter the gymnasium of red and blue lights, de Palma wields spectacular control over every cinematic element at his disposal, mounting suspense in long, delicately choreographed takes. Drifting above the crowd in a crane shot, the camera finds its way to a naïvely optimistic Carrie, and dreamily circles her and Tommy from a low angle as they begin to dance. While she is contained in her own blissful bubble though, believing they have both been nominated for Prom King and Queen, we also trace her bullies putting their plan to humiliate her into action. A tracking shot follows Norma swapping out real ballots for fake ones, before catching a glimpse of Chris and Billy hiding beneath the stage. With the dramatic irony laid on thick, we finally follow streamers to an overhead shot from the rafters, where a bucket of pig’s blood fatefully awaits its victim.

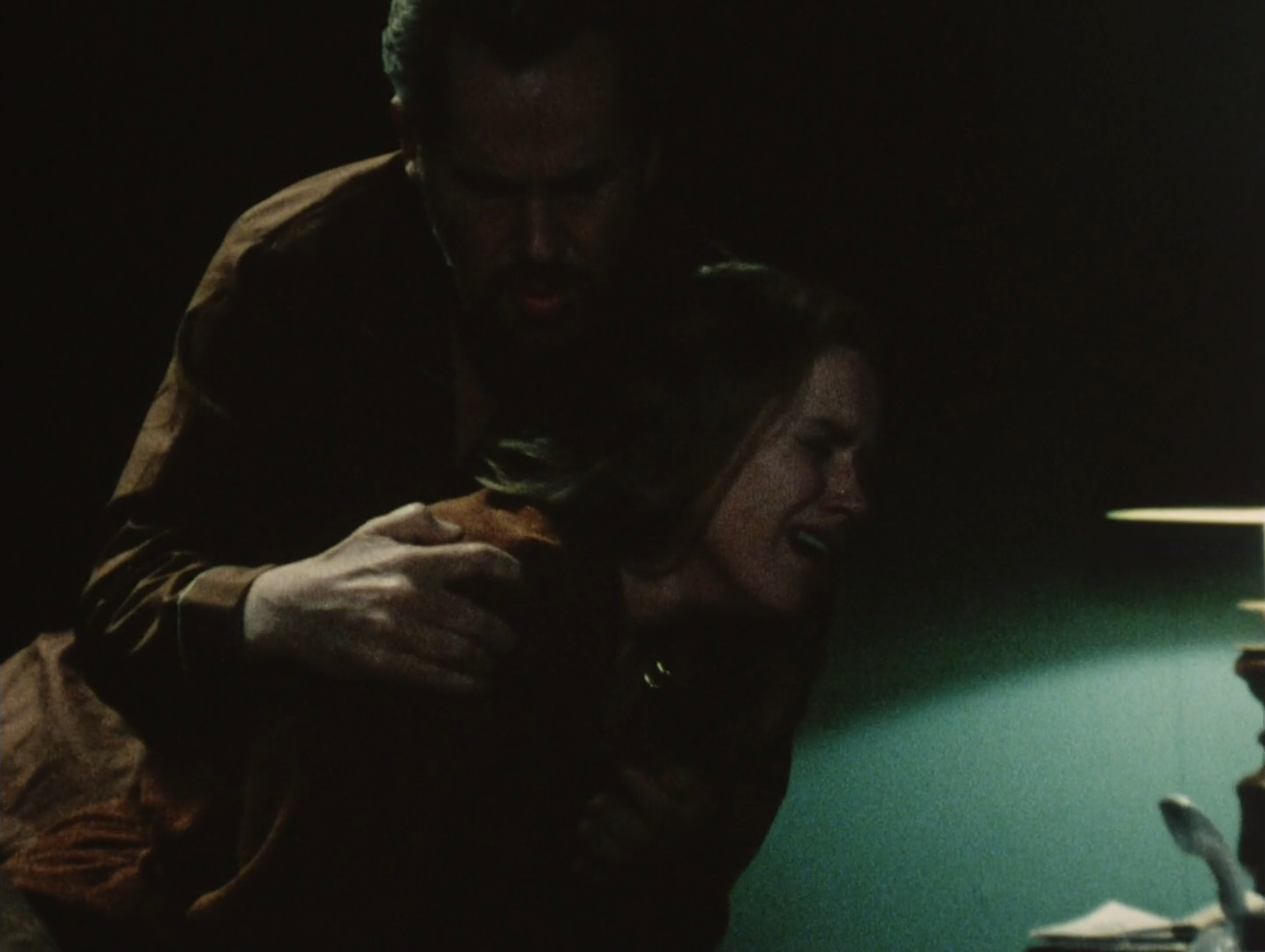

Hearing her name read out as Prom Queen seems almost too good to be true for Carrie, though who is she to question this unbelievable stroke of fortune? Heavenly strings and a dazzling white light accompany her as she approaches the stage, beaming a wide smile that feels almost foreign on her face, yet de Palma’s editing only ramps up the tension with its incredible slow-motion. The tone of Donaggio’s score continues to shift as we alternate between her ecstatic ignorance and the dread-stricken people around her realising that something is very wrong – not that any are quick enough to prevent the inevitable toppling of the bucket and her short-lived euphoria.

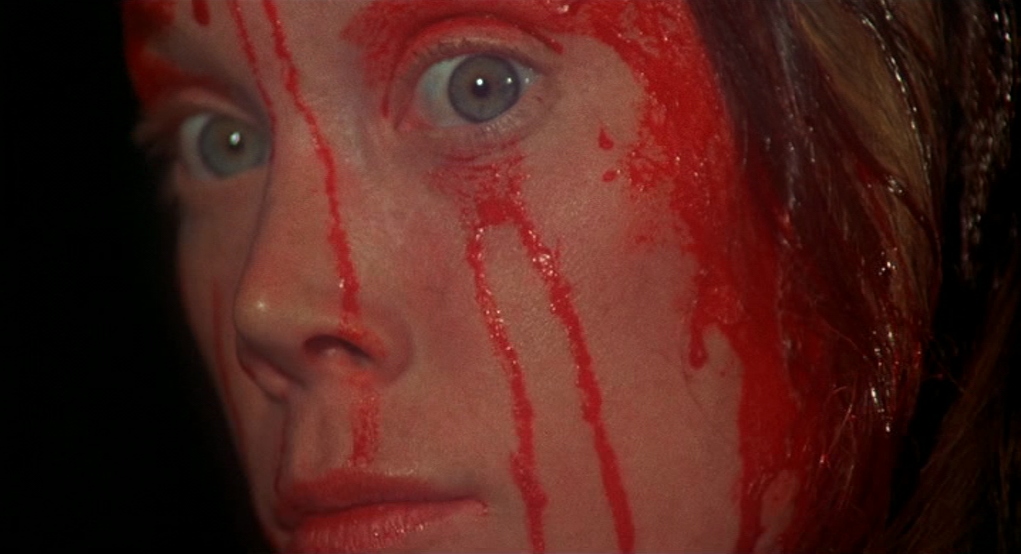

Just as blood ushered in the beginning of Carrie’s metamorphosis, it now completely douses her as she reaches her final, terrifying form. Whether menstrual or pig’s, it is a symbol of both evolution and suffering, inextricably bound together here as something inside her snaps. While many in the school gymnasium can only stare in silent pity, through her point-of-view we see them laughing as distorted hallucinations, and Spacek’s eyes widen in cold, merciless fury. The timid young girl is gone, and in her place stands a monster, refusing to distinguish between ally and foe. Everyone has their inner darkness, but while Carrie’s abusers have freely shown theirs to the world, an unimaginably crueller abomination within her has been raised, repressed, and finally released.

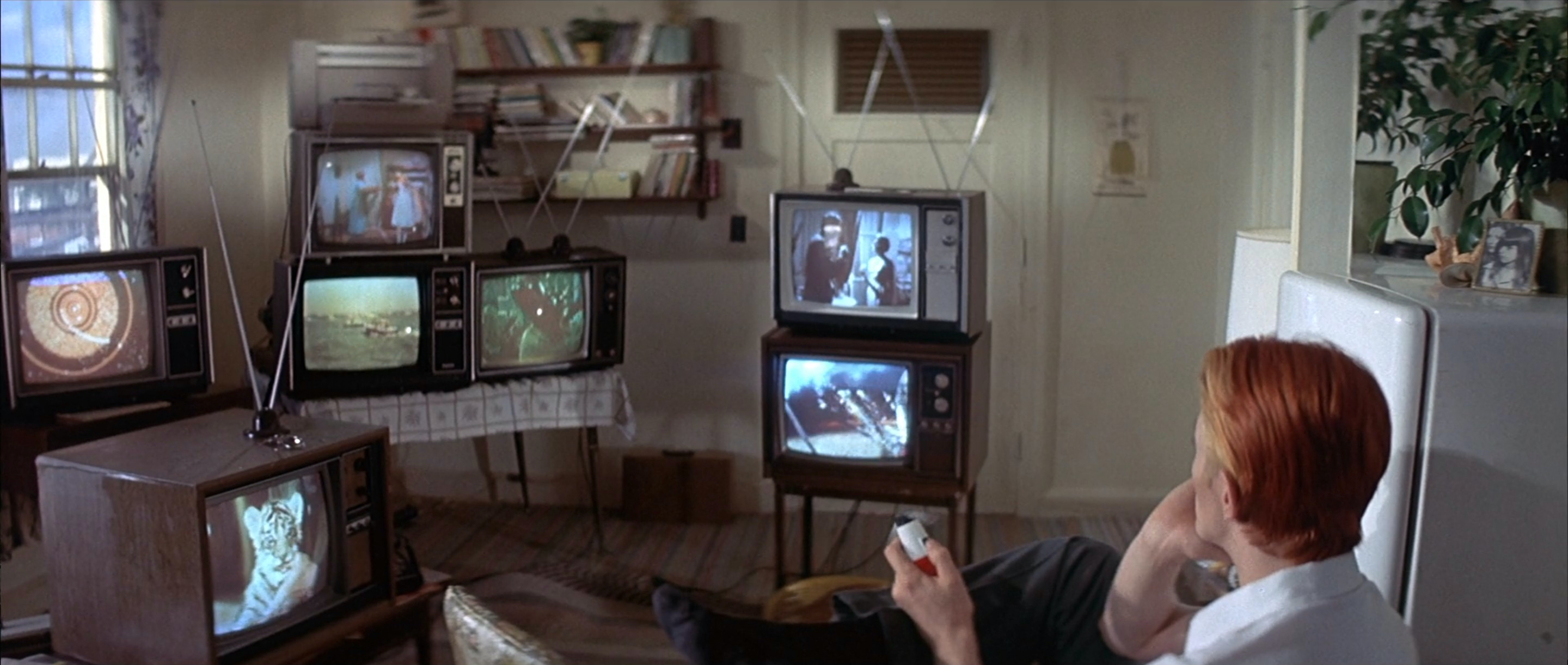

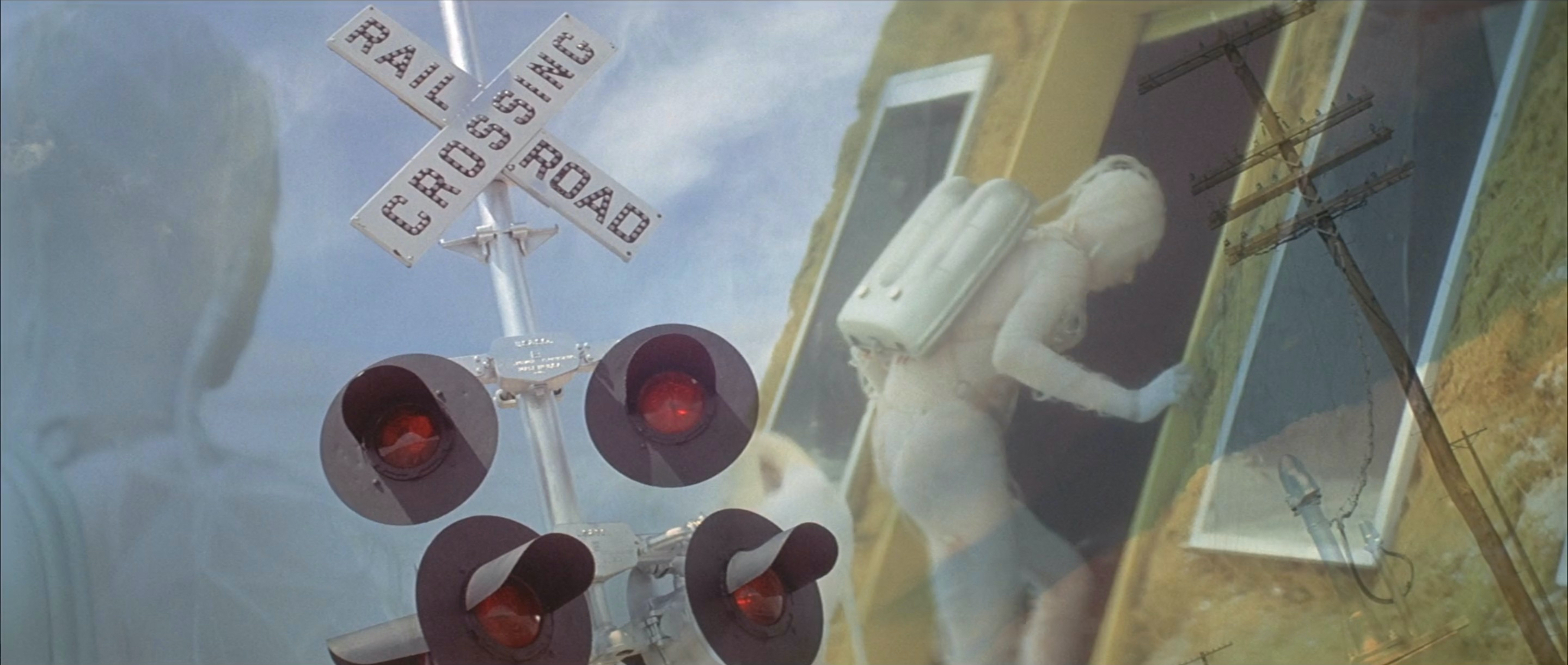

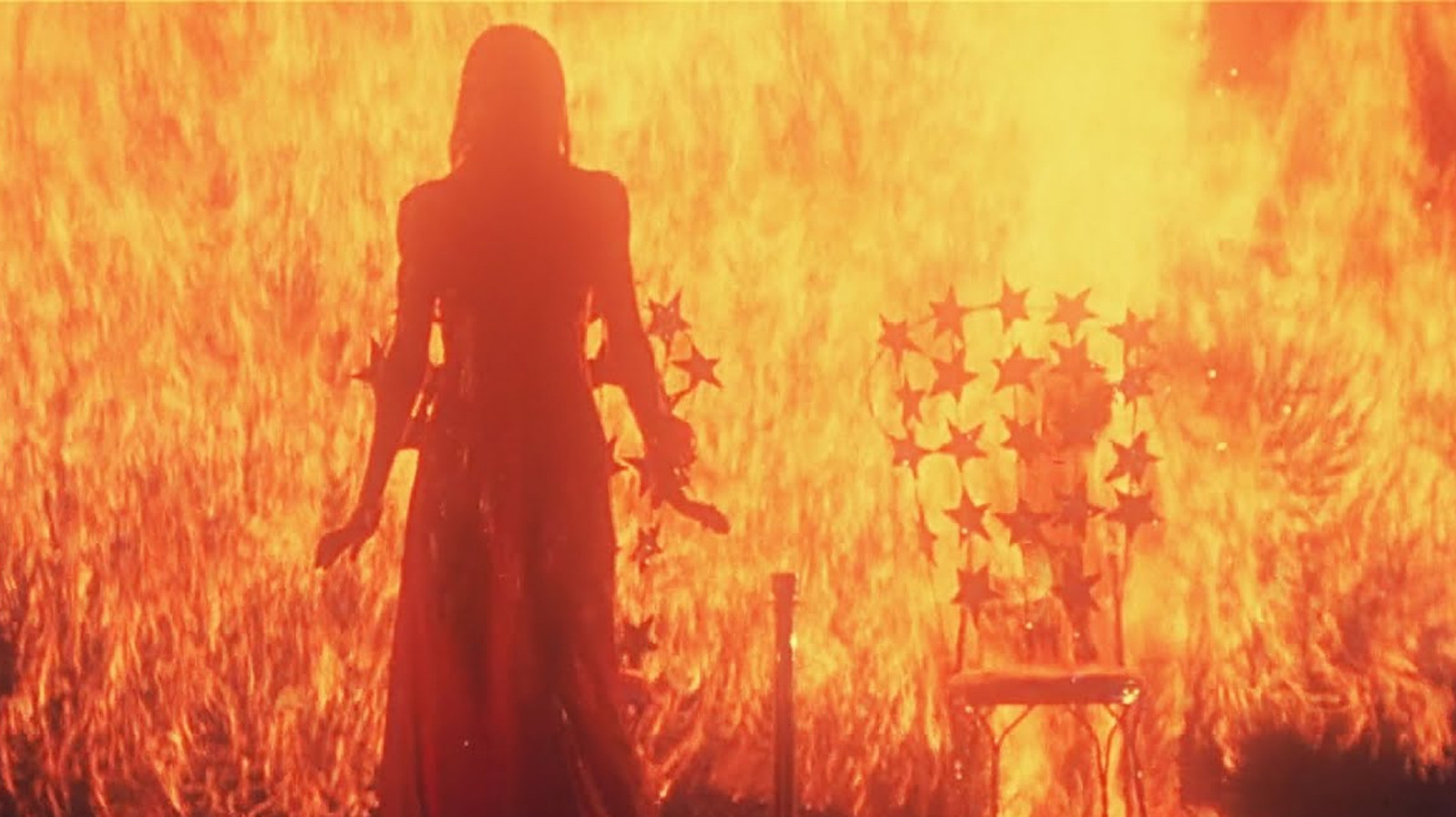

Split screens sharply divide the frame in two as she telekinetically slams the doors shut, piercing the audience’s defences with her unforgiving gaze on one side, and the other revealing her frightened victims. With a flick of her head, the stage lights bathe her in a hellish red wash, and the massacre begins. No longer do her powers lash out on impulse – now she wields them with perfect command, purposefully seeking to inflict as much harm as possible by turning the firehose on students, electrocuting the school principal, and crushing the only teacher who ever tried to help her beneath the basketball backboard. Silhouetted against a blazing fire, she strikes the image of a demonic queen in her blood-stained gown, and begins to walk in slow, stiff motions off the stage.

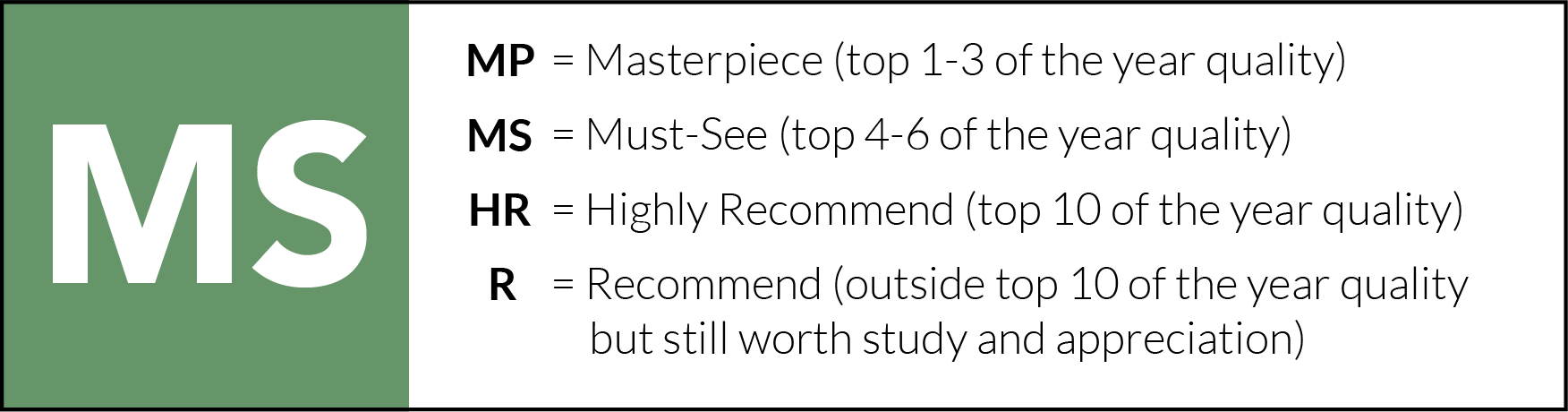

Although Carrie returns home, the nightmare is not yet over. As if preparing a ritual exorcism, her mother has lit the house with candles, though her entire demeanour seems drastically different. No longer the priggish disciplinarian, she confesses to the abuse she suffered at the hands of her late husband, the guilt she felt for her perverse pleasure, and the drunken rape which led to Carrie’s conception. Her daughter is the product of sin, she reasons, and though her logic is harsh, it is somewhat adjacent to the truth. More accurately, Carrie is the product of abuse, raised in a loveless home and carelessly twisted into violent killer.

That Carrie’s mother should perish in a pose that mimics the unsettling Saint Sebastian figurine is a perfectly ironic end for this supposed martyr. Pierced with knives, she hangs in an open doorway, suffering the consequences of her neglectful parenting. Still burdened by a self-loathing conscience, Carrie is close to follow her into the darkness as well, collapsing the entire house and ending her rampage with herself as the final victim. The jump scare that de Palma sneaks into the final scene not only haunts the prom night’s sole survivor, but also points to the skewed legacy left in her wake. Carrie is not to be remembered in this town as a victim of immense tragedy, or a teenager struggling to comprehend strange physiological changes. She is a ghost who lives on in nightmares, whispered between neighbours as a local legend, and exacting the trauma she once suffered back on the world a thousandfold and more.

Carrie is currently streaming on Stan and Amazon Prime Video, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.