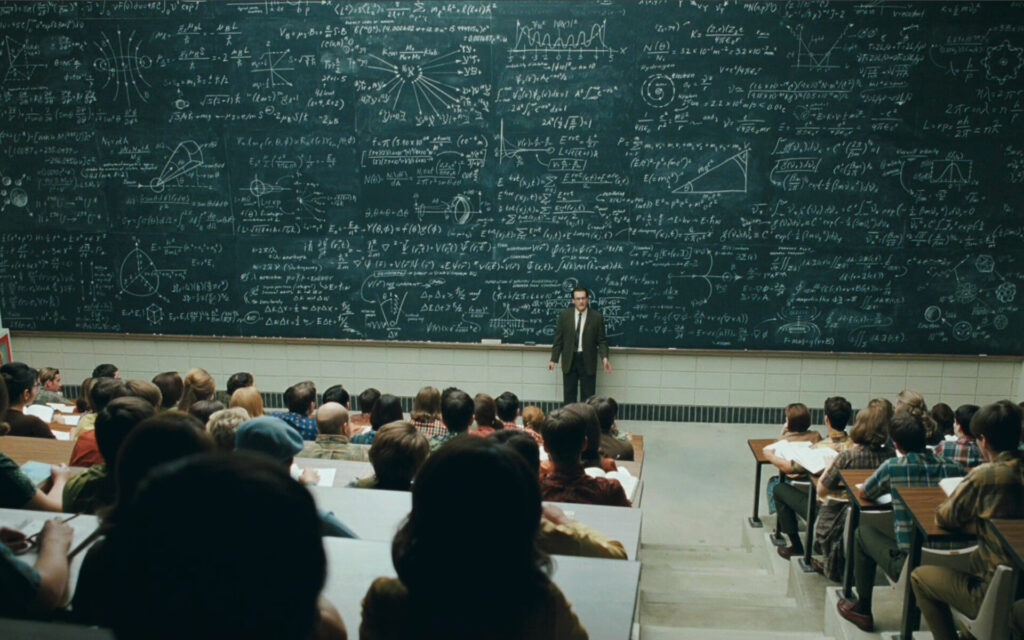

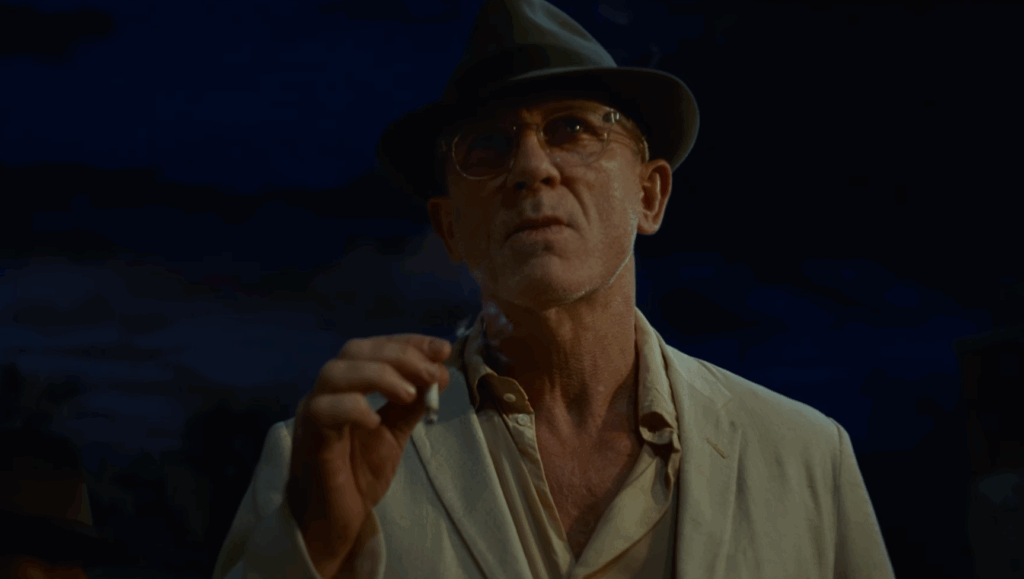

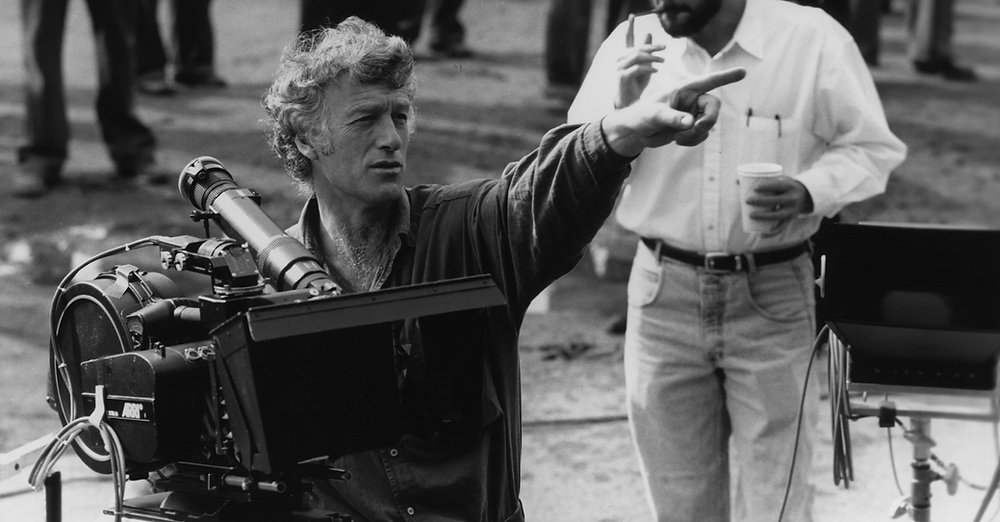

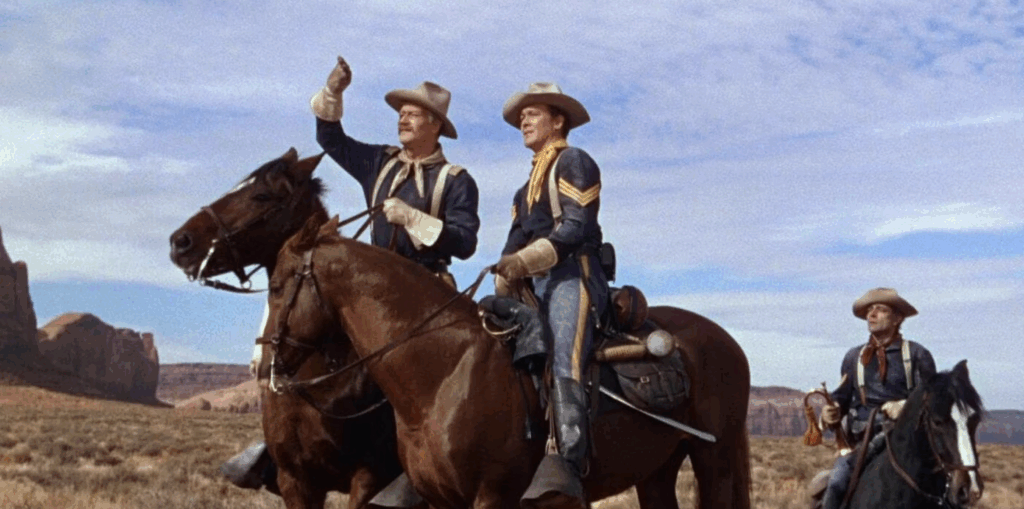

Zero for Conduct (1933)

The rule of law is little more than an arbitrary imposition of authority in Zero for Conduct, and it is up to the roguish schoolboys of one French boarding school to restore the natural order, as Jean Vigo playfully mounts a rising disenchantment towards anarchic revolution.