Denis Villeneuve | 2hr 46min

“Power over Spice is power over all,” chants an unseen Sardauker priest in the opening prologue of Dune: Part Two, though what exactly that signifies varies drastically depending on who wields it. For the native Fremen, Spice is a key component of everyday products, while its value as the rarest commodity in the universe guarantees wealth and status to whichever Great House rules Arrakis. As for Paul Atreides, its implications are far more mystical. It is through Spice that he is granted the prescience to see himself leading a Holy War as a Messiah destined to lead the Fremen towards liberation, as well as the means through which he may control an even greater resource – the zealous faith of millions.

As tremendous as Denis Villeneuve’s epic achievement was in the first instalment of Dune, it is clear with the context of Part Two just how much of that was simply setting up Paul’s subverted monomyth, where we witness his evolution into one of cinema’s great antiheroes. Lawrence of Arabia is the clearest comparison to draw given its challenging of a ‘white saviour’ who leads foreign civilisations through unforgiving deserts and into battle, though The Lord of the Rings trilogy seems more fitting. When entering production, both Peter Jackson and Villeneuve were respectively met with the obstacle of adapting ‘unfilmable’ material, but with sharpened instincts for strong visual storytelling and a recognition that such expansive narratives cannot be confined to a single movie, both also defied the scepticism of critics.

To draw the similarities closer, the foundations of these grand narratives are rooted even deeper than Frank Herbert or J.R.R. Tolkien’s writing. These are stories of theological significance, interrogating notions of spirituality through symbols of prophecies, resurrections, and salvation, especially with Dune framing Paul as a saviour descended from the skies of Arrakis to cleanse the world – or the universe – of evil.

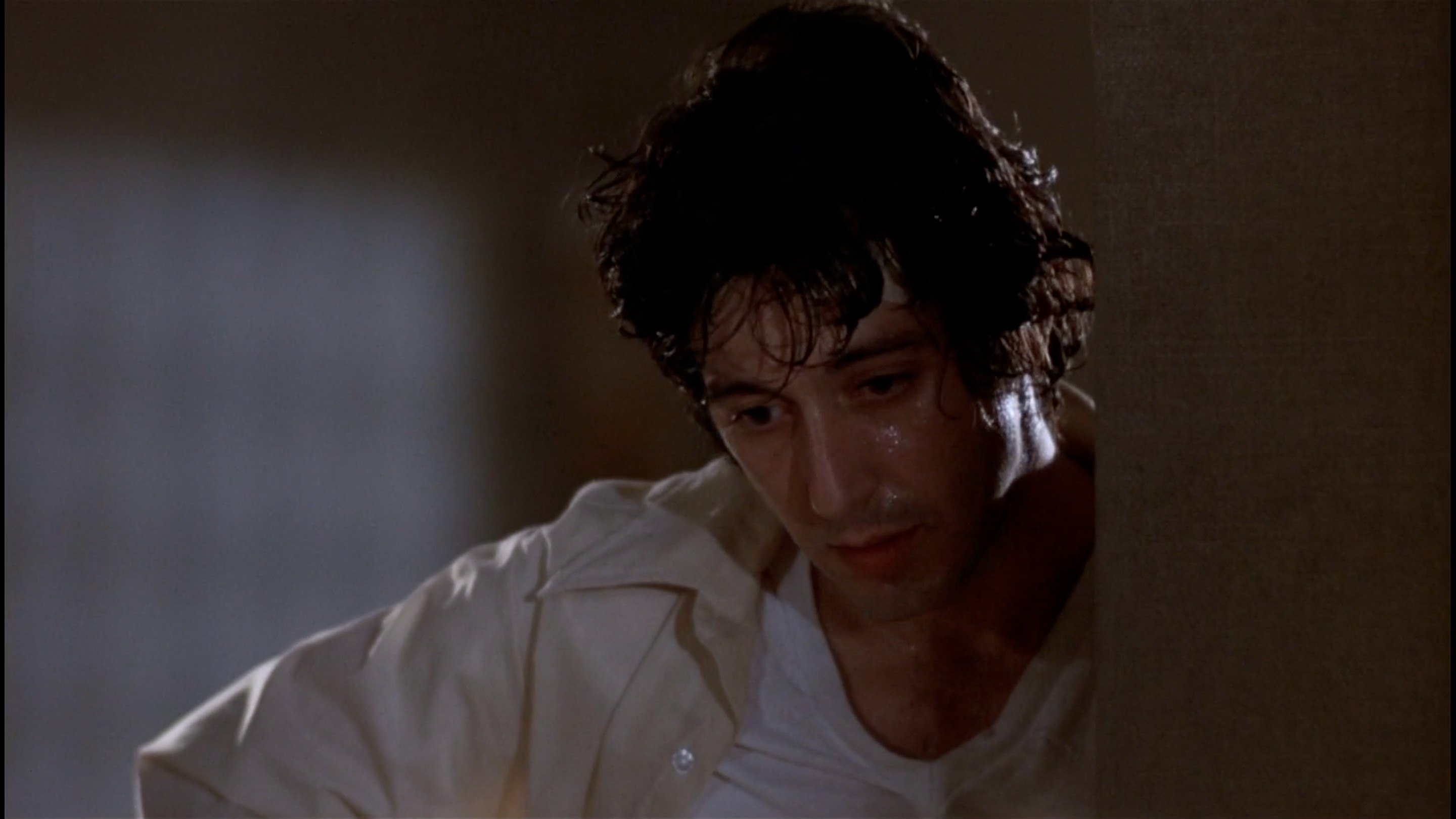

Timothee Chalamet’s return in this role only continues to prove why he is one of the most promising actors of his generation as well, mirroring Anakin Skywalker’s descent into darkness, though with a far firmer grip on his character than Hayden Christensen. Beautifully fragmented dreams of the war and starvation he will wreak haunt him in ethereal slow-motion, cautioning against his journeying south, and yet the pull of fate eventually proves to be too strong. By the time he is standing upon platforms and delivering rousing speeches to followers and enemies, his voice has shifted down to a deeper, gravelly register not unlike the Baron’s, and he exudes a megalomania that leads us to mourn the humbler Paul we met in Part One.

Villeneuve’s build to this apotheosis is carefully paced in Part Two, confronting Paul with a series of challenges he must complete to meet his destiny. The iconic sandworm ride arrives about an hour into the film as his first major milestone, and Villeneuve doesn’t waste its potential as a defining moment of his directing career, anxiously building anticipation as currents of sand ripple through the desert like waves before it is kicked up into a furious, dusty tempest. The lack of detail in Herbert’s book around how one rides these sandworms gives Villeneuve the freedom to creatively imagine the act with hooks and ropes, bringing a tactility to the scene that is magnified by the camera’s immersion in the thick of the action, while only occasionally cutting back to the Fremen who distantly watch in reverent awe. The guerilla warfare Paul wages with them against invading Harkonnen forces similarly gives shape to their customs and practices, as even with limited resources, their stealthy manipulation of the natural terrain allows them to easily overpower their armoured enemies.

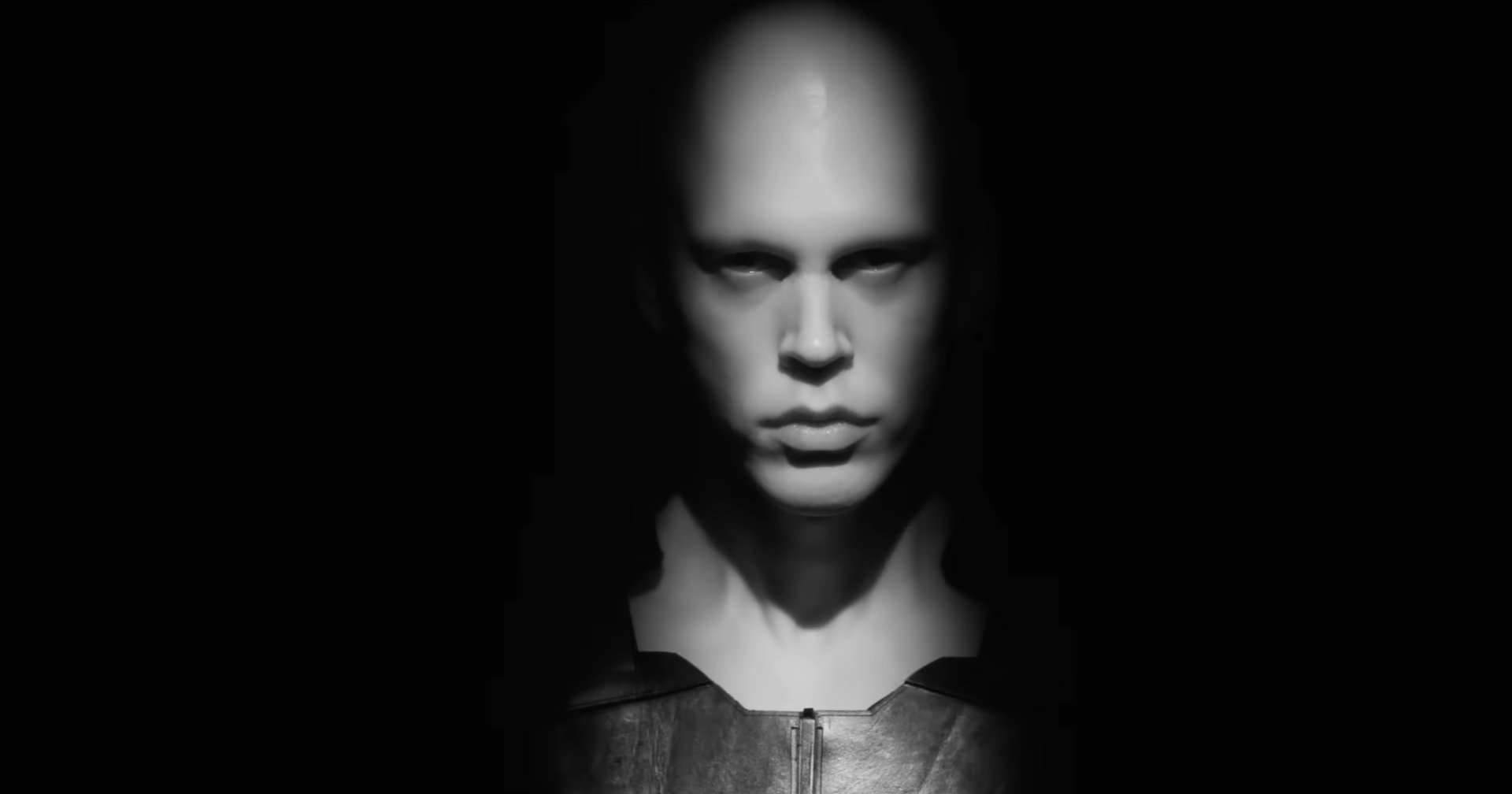

Freed from Part One’s pressure of setting up this epic narrative, it is clear in instances like these that Villeneuve feels more comfortable experimenting with a greater sense of visual wonder and terror. Silhouettes set against blinding white landscapes and close-ups of Spice glistening upon the sand are carried over here from the first film, while the burnt orange magic hour lighting calls back to the radiation polluted Los Angeles of Blade Runer 2049, yet Dune: Part Two especially excels when it begins exploring more far-flung lands. The fundamentalists who live in the south of Arrakis are acutely distinguished from their northern counterparts, not only by their barren plains of dark rock, but Villeneuve also captures their culture of devout worship in a dazzling overhead shot that loses their Paul in a sea of pale headdresses.

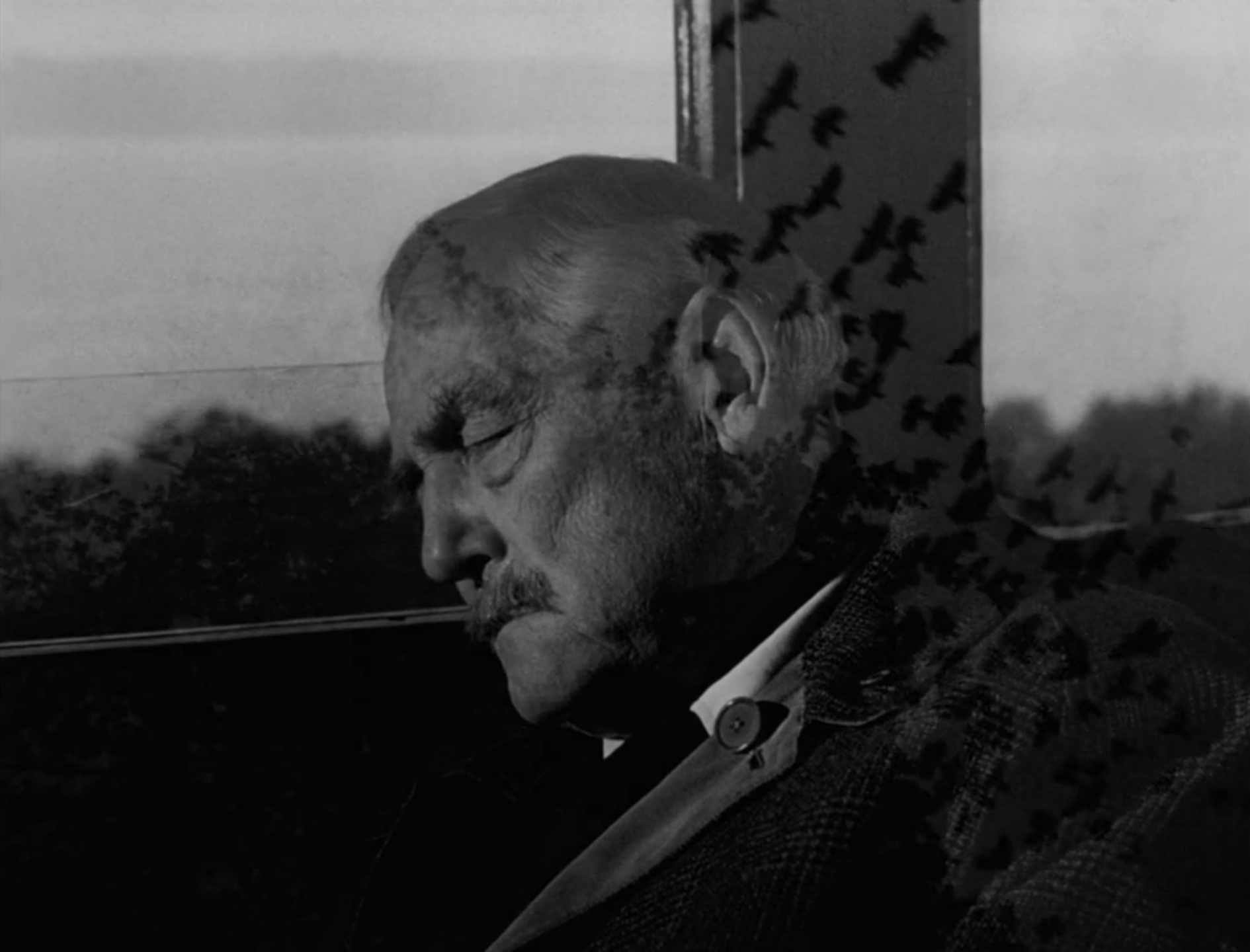

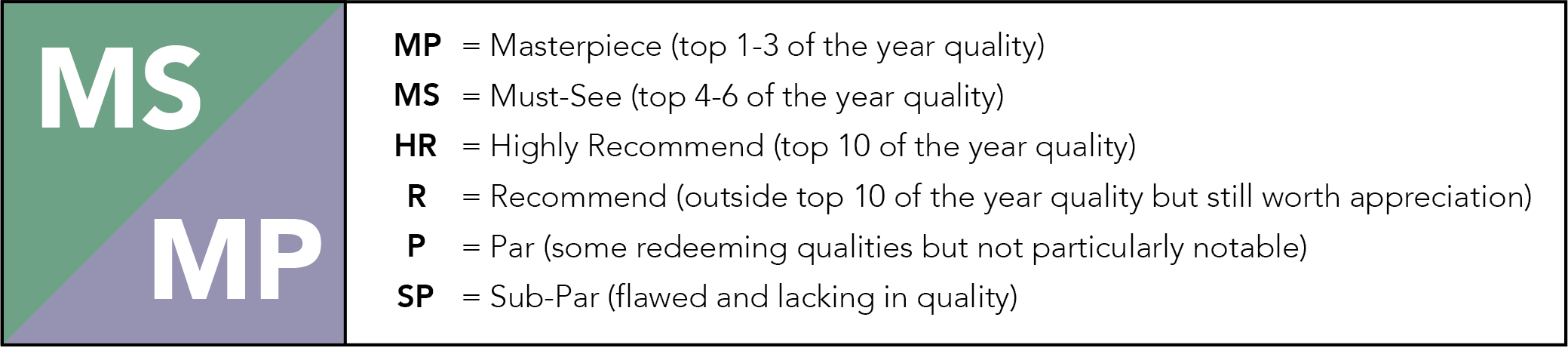

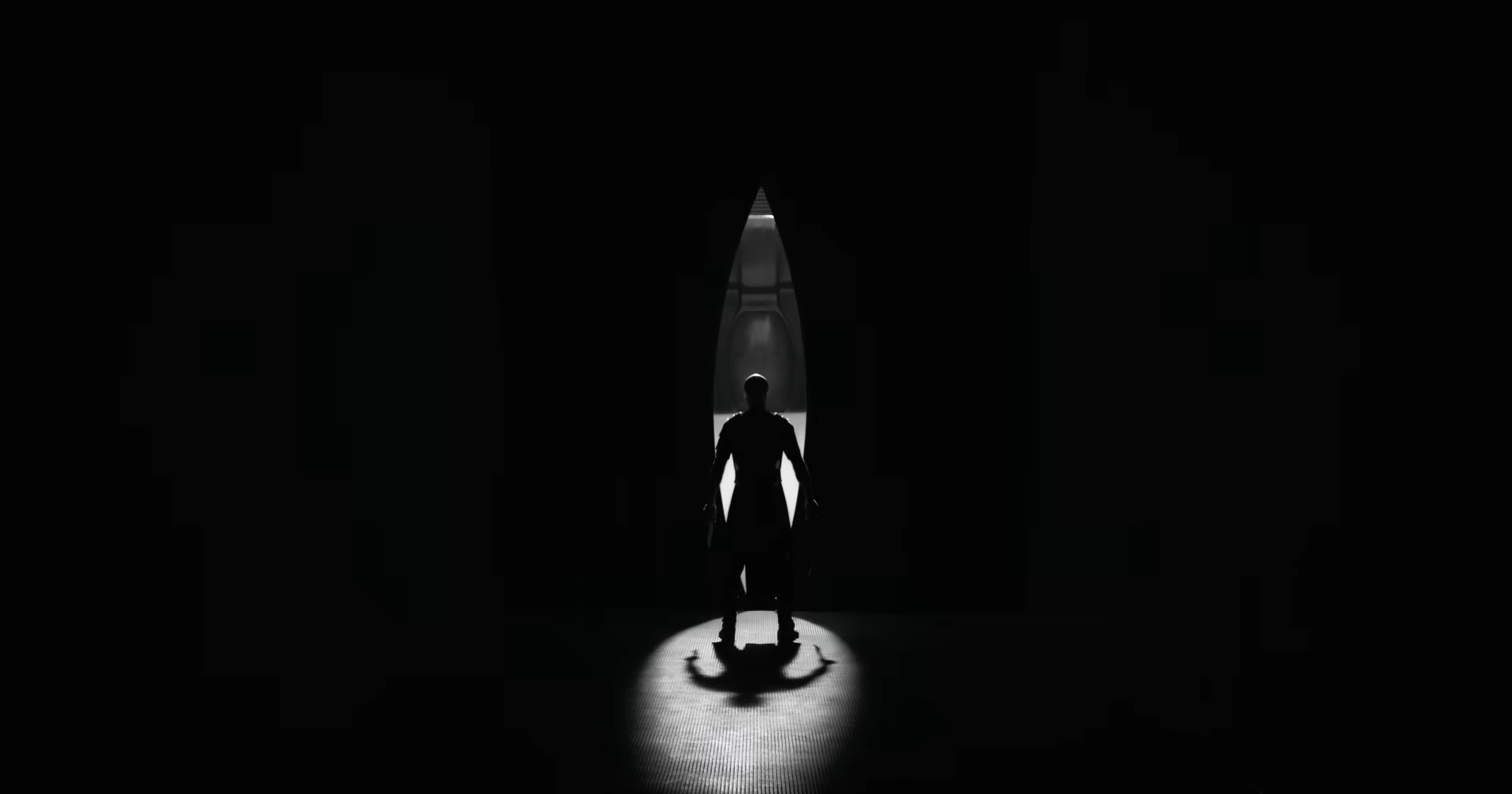

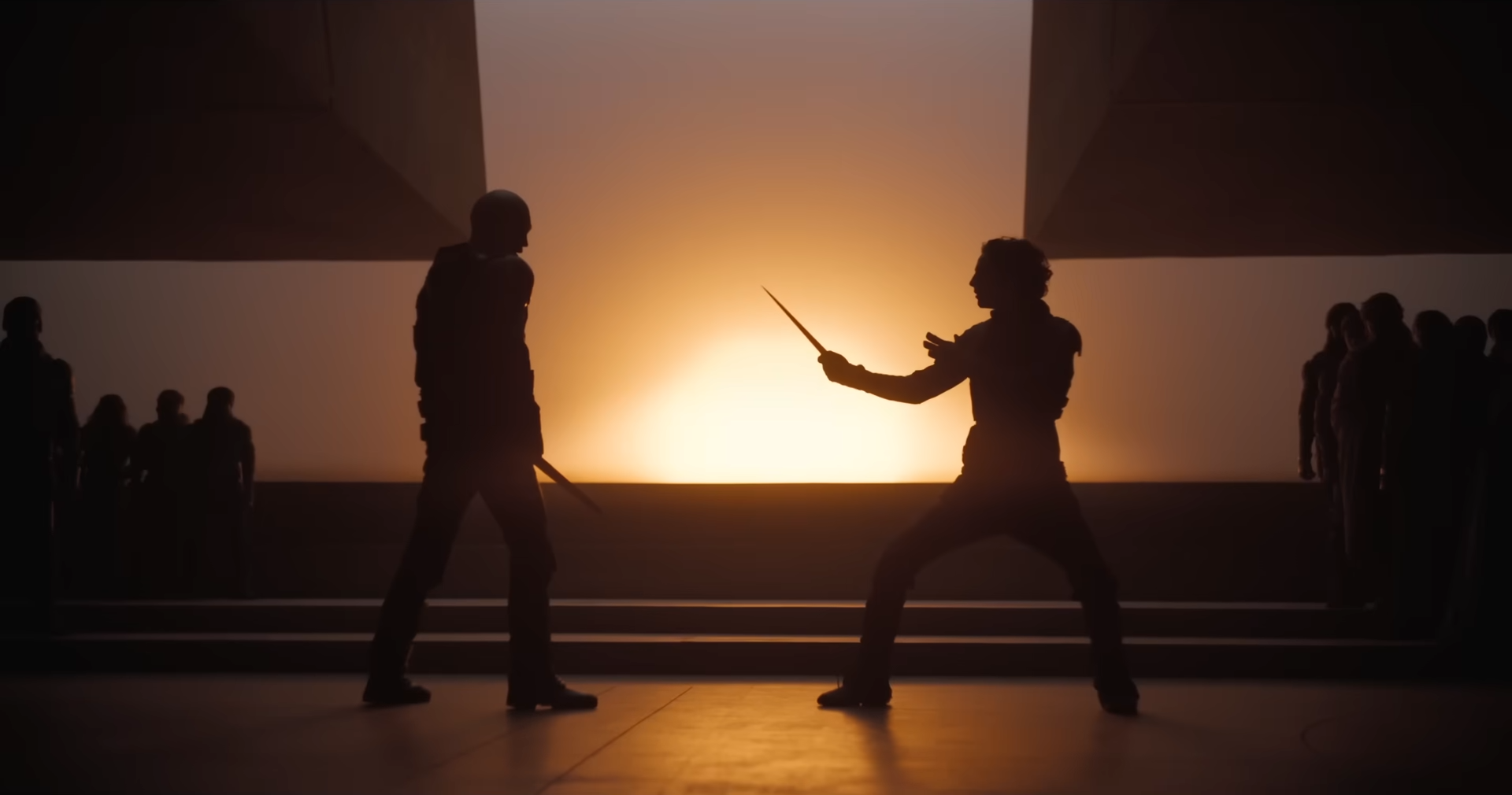

Even more astonishing though is our extended stay on Giedi Prime, home of House Harkonnen, whose desaturated exteriors are as splendidly severe as their brutalist interior architecture. Where Arrakis’ skies are distinguished by their double-eclipsed, crescent sun, here the land is cast under a black sun, absorbing any colour that falls beneath its rays. Cinematographer Greig Fraser’s decision to shoot these scenes with a black-and-white infrared camera accomplishes an eerie monochrome aesthetic, and stylistically sets the austere tone for the psychopathic, reptilian Feyd-Rautha, youngest nephew of the Baron. Within the gladiator arena filled with bloodthirsty spectators, he viciously slaughters a trio of survivors from House Atreides for his birthday celebration, and from there is effectively set up by the Bene Gesserit sisterhood as a foil for Paul in contest over the sovereignty of Arrakis.

After playing Elvis Presley in Baz Luhrmann’s biopic, Austin Butler couldn’t have chosen a more different character to follow that up with than Feyd-Rautha, stripping away his natural charisma and replacing it with pure derangement. He stands among the strongest of the supporting cast, right next to Rebecca Ferguson whose dark journey as Lady Jessica in Part Two mirrors Paul’s Messianic ascension, and Javier Bardem whose comic beats as Stilgar miraculously do not hamper the weight of Villeneuve’s drama. Zendaya meanwhile leaves slightly less of an impression as Chani, though it is Christopher Walken who delivers the weakest performance of the lot, lacking the presence needed to play the Emperor.

Still, each of these parts play an integral role in Villeneuve’s strategic manoeuvring of his pieces towards a roaring climax, supplemented by a score from Hans Zimmer that intrepidly builds on the war cries and blaring electronic orchestrations from Part One. As the Emperor’s enormous ship drifts over Arrakis, Villeneuve’s low angle anxiously gazes up at its metallic underside distorting reflections of the mountains below like an ominous warning of colonial subjugation, and leads into an explosive battle which has us questioning Dune’s hazy divide between good and evil. So brilliant is Villeneuve’s direction here though that the smaller-scale duel which follows can’t help but feel like a step down in stakes, and perhaps would have been better positioned earlier as part of the rising tension.

If the Dune series is to end here with a gutting fulfilment of Paul’s hero’s journey, then it would at least be a complete story unto itself, though Villeneuve’s teasing of Dune Messiah certainly remains a tantalising prospect. His ability to build on existing science-fiction material was already evident in Blade Runner 2049, and now his work committing Herbert’s unfathomably vast imagination to film additionally demonstrates his own, pushing the limits of big-budget spectacle to extraordinary lengths. When it comes to fully realising its elemental iconography and grand narrative on a cinema screen, Dune’s insurmountable parable of fanatical hubris deserves nothing less.

Dune: Part Two is currently playing in cinemas.