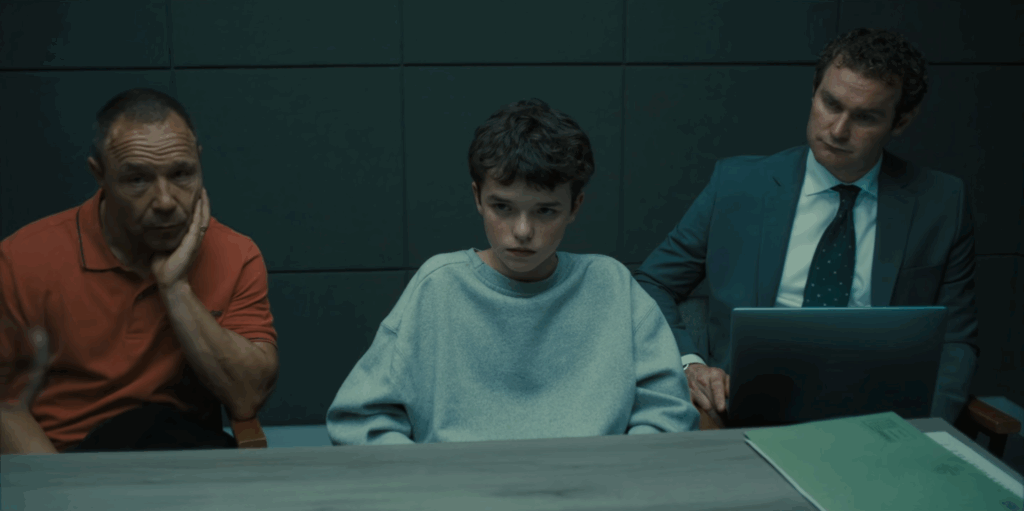

Ossessione (1943)

Luchino Visconti masterfully merges neorealism with the dark, fatalistic tension of film noir in Ossessione, unravelling a deadly affair between a pair of down-on-their-luck strangers, and revealing the inescapable consequences of passion, resentment, and poverty.