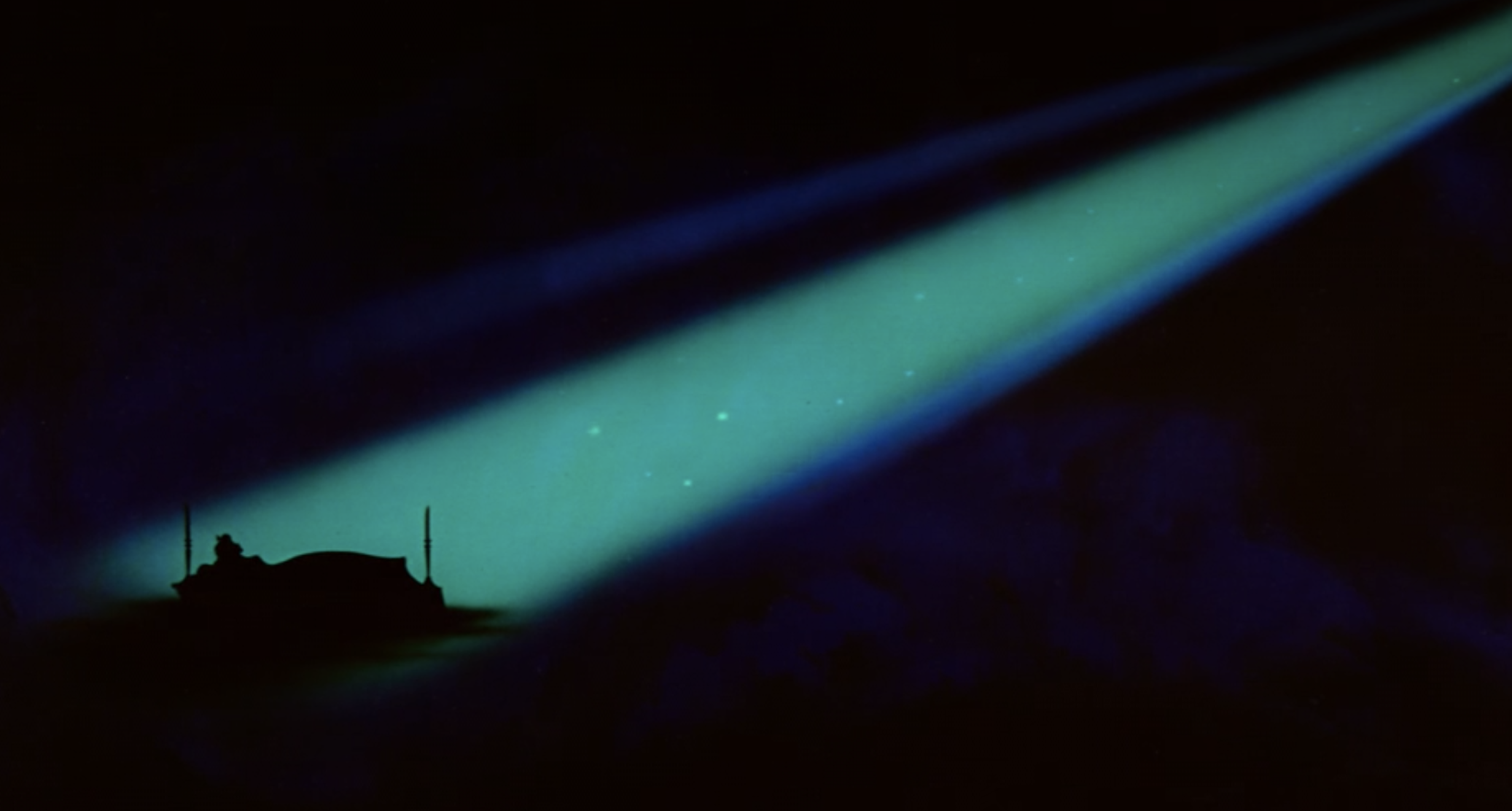

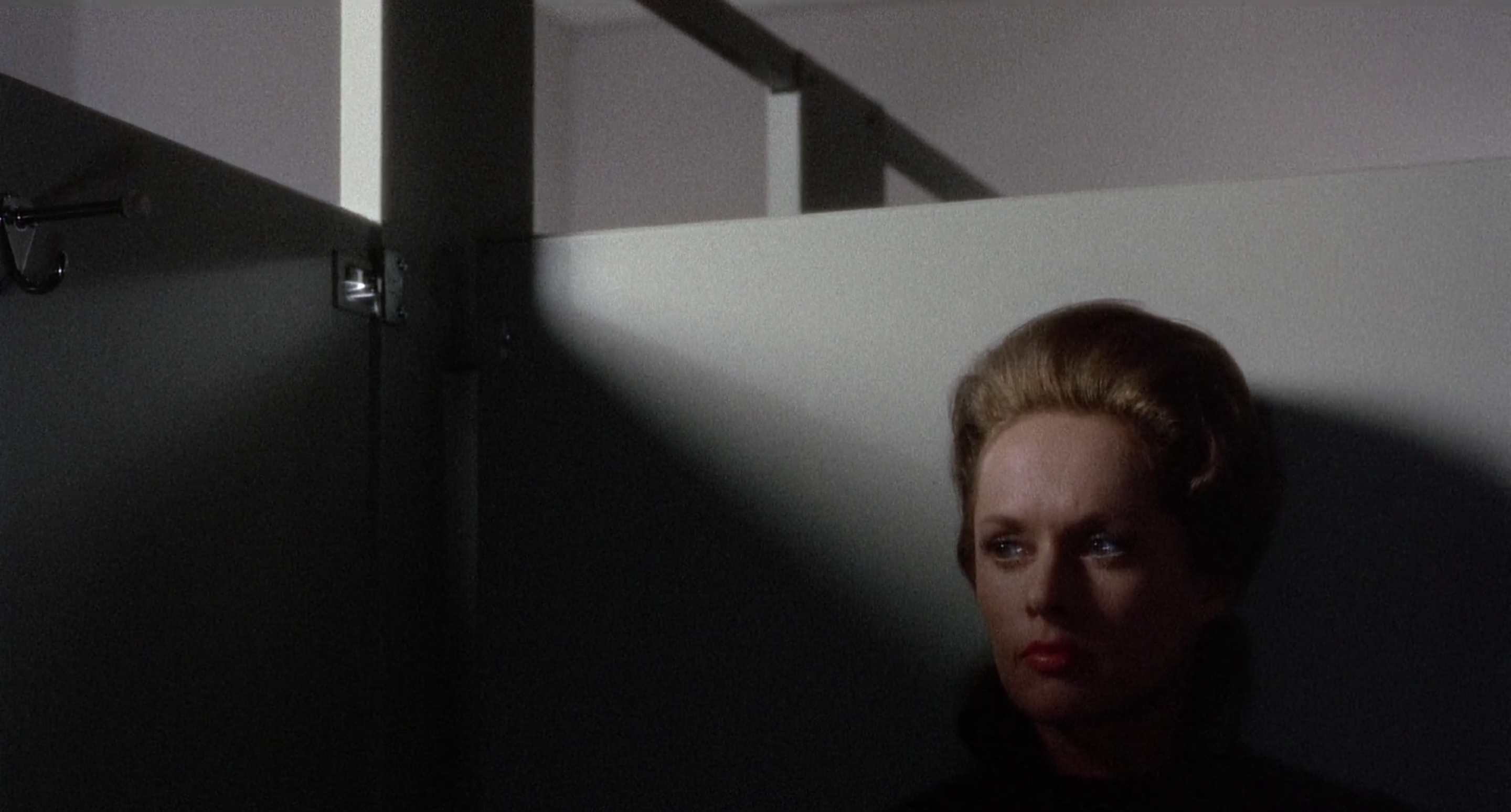

Sleeping Beauty (1959)

In using the full scope of its widescreen format, Sleeping Beauty creates the layered look of Renaissance tapestries hand-drawn on canvas, effectively infusing the whimsical style of its narrative into its dreamy imagery and delicate orchestrations.