The Fabelmans (2022)

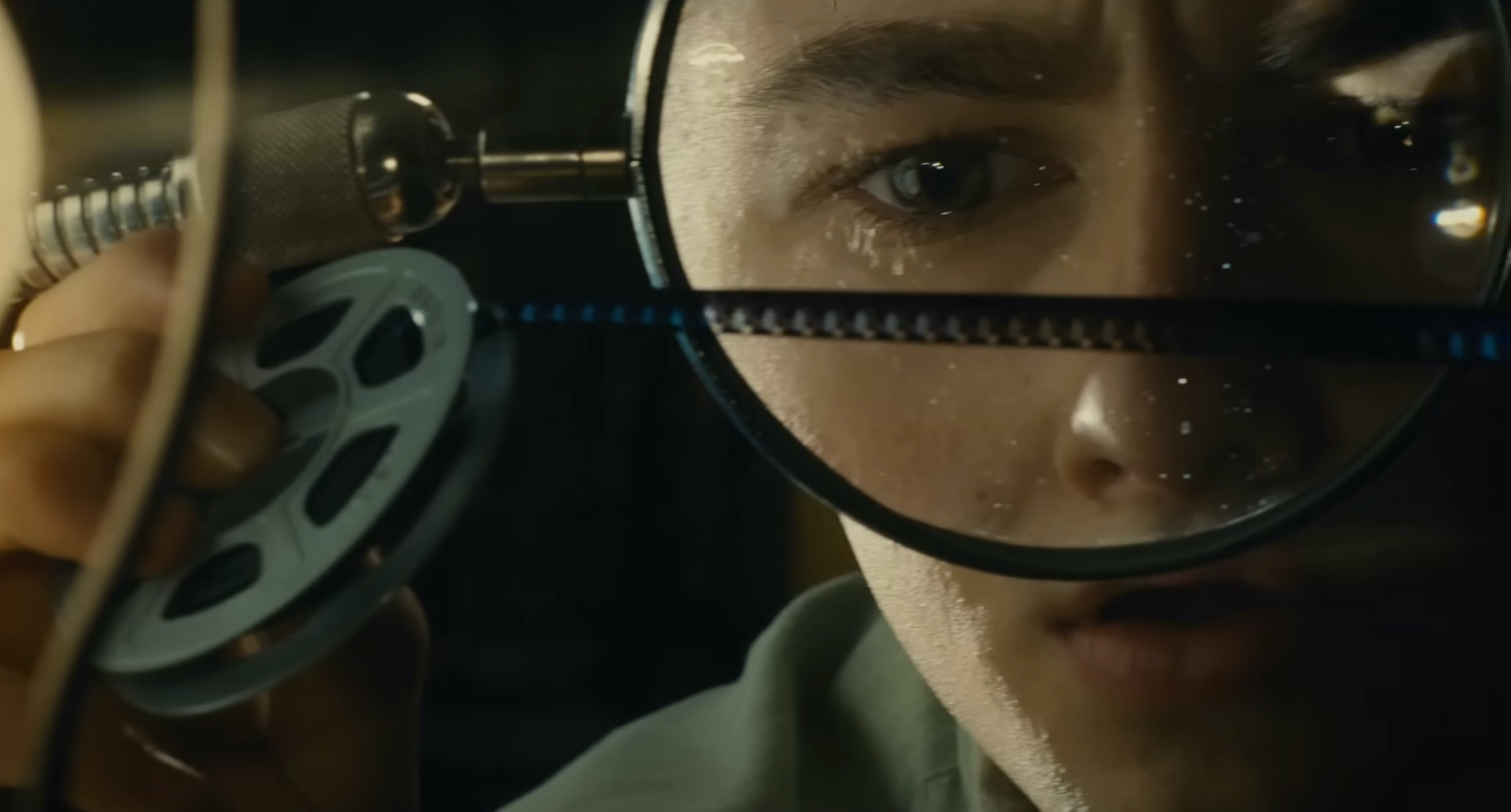

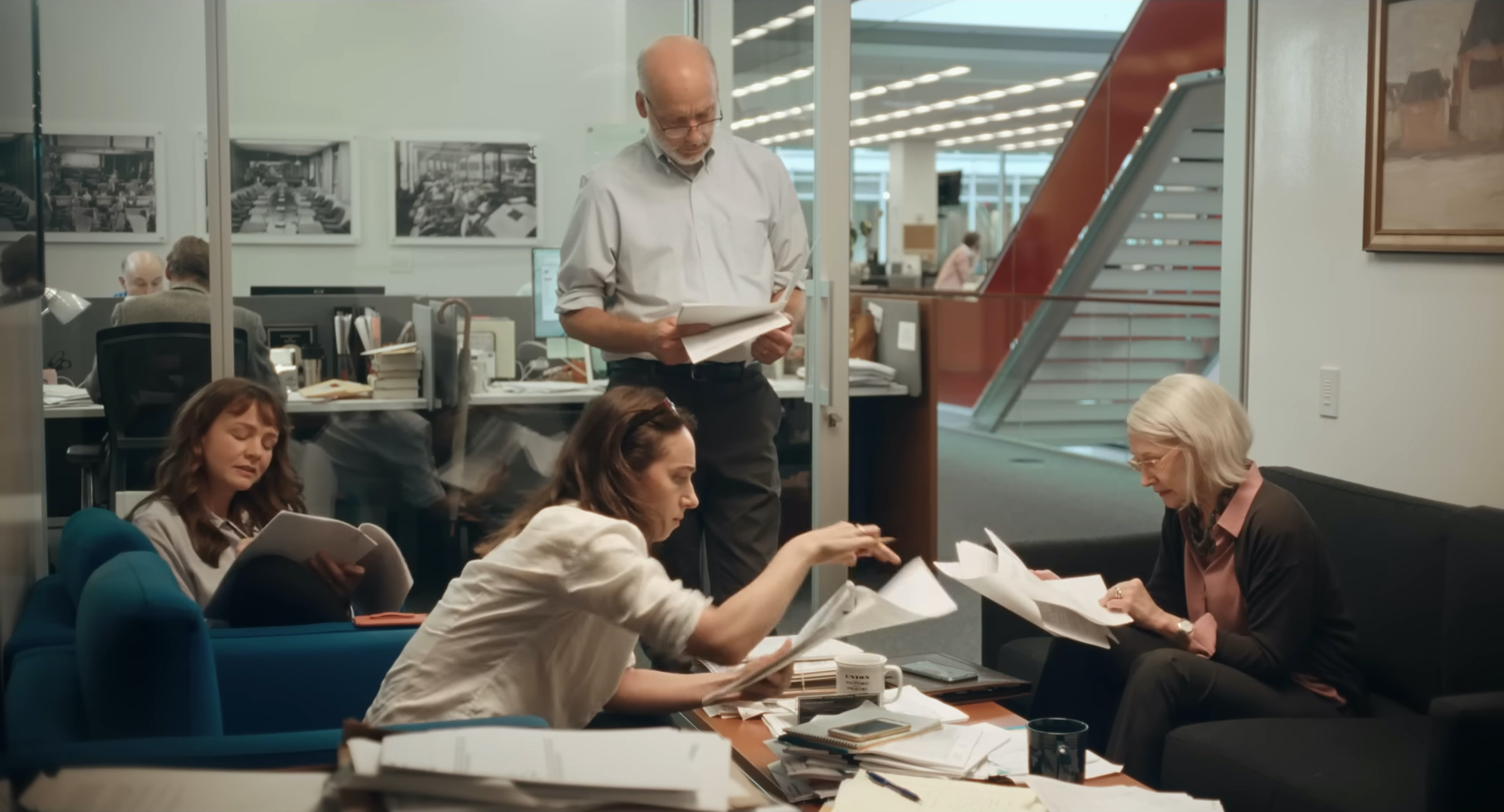

Despite the odd flash of visual inspiration and dissection of cinema’s raw power, The Fabelmans is not so interested in pushing formal boundaries than offering a pure insight into the youth of its own director, Steven Spielberg, whose memories, fears, and passions eloquently flow through what is his most personal film yet.