Steven Spielberg | 2hr 31min

In Steven Spielberg’s autobiographical memory piece The Fabelmans, moviemaking is a superpower for young Sammy Fabelman. As a child, his miniature reconstruction of a frightening train crash he witnessed in The Greatest Show on Earth helps him understand his terror by first controlling it, then putting it out into the world. As a teenager, he learns how he can shape others’ perceptions of reality to his own choosing, forcing his high school bully to undergo a personal, emotional reckoning by framing him as a hero. The heartbreaking compilation he cuts together of brief glances shared between his mother, Mitzi, and family friend, Bennie, carries the power of both these short films. It is simultaneously a way for him to pour out anxieties regarding his parents’ crumbling relationship, and also a message to Mitzi of the pain she is inflicting on her own children.

Sammy’s love of watching and making films may be his driving passion, and yet throughout so much of The Fabelmans it is merely secondary to the drama going on elsewhere. The implication of storytelling is only barely concealed within the family’s name, which itself is only a thin cover for the real people they are based on – the Spielbergs. The famed director of blockbusters and historical films turns his camera on his younger self here in what may be his most personal work yet, piecing together vignettes of his youth in a concerted effort to understand where his identity and art intersect. His Jewish heritage is an integral part of that, but so too are the tiny quirks that make his family so unique, such as their tradition of only using paper plates at dinner so Mitzi doesn’t have to damage her piano-playing hands while washing dishes. The eventual separation of his parents carries on a poignant thread of divorce that has lingered on the edges of many other Spielberg films too, and here he gets to the root of that childhood trauma via the affecting performances of Michelle Williams and Paul Dano.

Spielberg goes to great lengths to instil these evocative memories with authenticity, not just decorating his home interiors with patterned wallpaper he recalls from the 60s, but even recreating his early amateur films shot-for-shot. After watching The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Sammy feels inspired to make a Western, and as the camera tracks backwards out of the wagon he has hired, his dad is amusingly revealed off to the side blowing dust into it. In another scene, a cluster of dead men quickly stand up, run behind the moving camera into their second position, and fall to the ground again for the end of the shot, creating the illusion of more extras than there actually are. The comedy of these scenes dissipates the moment we watch the finished cuts though, as Sammy moulds his reality into stories that enrapture his fellow scouts and students.

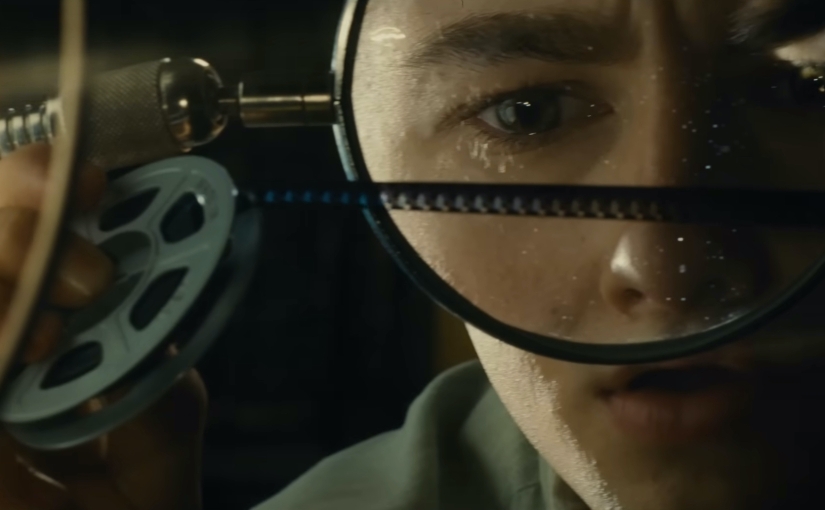

Spielberg’s own camera becomes actively excited too in the processes of filming, editing, and projecting movies, floating through sets in tracking shots and circling Sammy’s head as he sits at his editing machine, closely inspecting a tiny detail in his family movie that will soon change his entire life. So too is there some lovely depth of field in his cinematography, soaking in the period décor of Sammy’s multiple childhood homes, and yet it is somewhat disappointing that this celebration of cinema does not see Spielberg push the visual artform further as he has done in the past.

The Fabelmans may not be among Spielberg’s best films, though it is certainly at least one of his funniest, letting the awkward moments of adolescence roll by in Sammy’s first romance as he finds himself on his knees in the bedroom of a Christian girl intent on converting and seducing him at the same time. David Lynch’s cameo appearance as Sammy’s idol John Ford is similarly played for laughs, but the huge significance of this scene is not at all lost in the humour, drawing directly from Spielberg’s own experience as a young production assistant. He has recounted this brief meeting in many interviews, though to see it play out cinematically feels even more monumental. Cinephiles will immediately recognise the music from the opening of The Searchers as the camera pans around the waiting room adorned by posters of The Quiet Man, Stagecoach, and The Grapes of Wrath, and the lesson that Ford instils in the young aspiring filmmaker also rings true in its own funny way.

“When the horizon’s at the bottom, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s at the top, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s in the middle, it’s boring as shit.”

There couldn’t be a more perfect ending to this film’s thoughtful consideration of cinema’s raw construction than the final visual gag that references this teaching, breaking the fourth wall in such a Godardian manner that makes you wish the film was always this inventive. As it is though, The Fabelmans is not so interested in pushing formal boundaries than offering a pure insight into its director’s youth, seeking the source of his greatest and most tragic inspirations. Sammy may often come off as an ordinary kid throughout the film, but just as we put immense faith in Spielberg to pull at our heartstrings with the tools of his craft, his younger surrogate looks like the most confident, powerful man in America the moment he picks up a camera.

The Fabelmans is currently playing in theatres.

2 thoughts on “The Fabelmans (2022)”