Mike Leigh | 2hr 11min

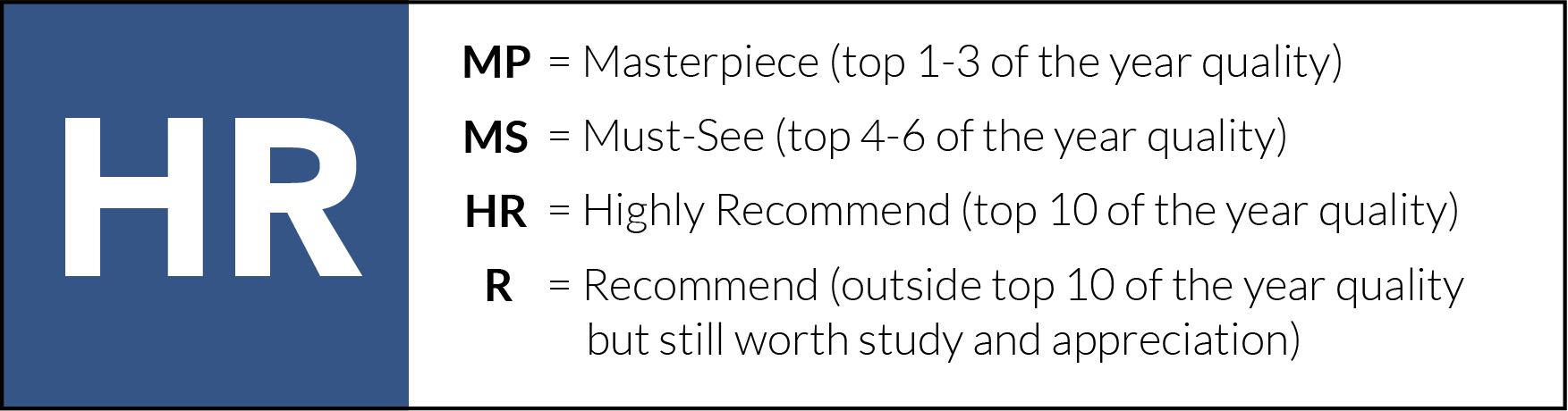

Like a demon rising from some dark pit to inflict as much misery on society as possible, or a man ready to tear the world down with him on his way to hell, there is no real direction to Johnny’s nocturnal wandering through the city streets of London. He might very well be the most intelligent person he has ever met, though this would also be the kindest thing one could say about him. The only way he can practically apply his extraordinarily quick wit and abstract philosophising is in targeting the vulnerable, who inevitably feel enough loneliness, pity, or curiosity to invite him into their lives. His knack for rapidly gaging their weaknesses is impeccable, whether it is a security guard’s distant dream of retiring to Ireland or a middle-aged woman’s desperate longing her youth, and from there his takedown is swift and vicious. He talks fast, speaking of conceptual theories far beyond his target’s comprehension to beat them into a gloomy submission, before moving onto whoever is unfortunate enough to cross his path next.

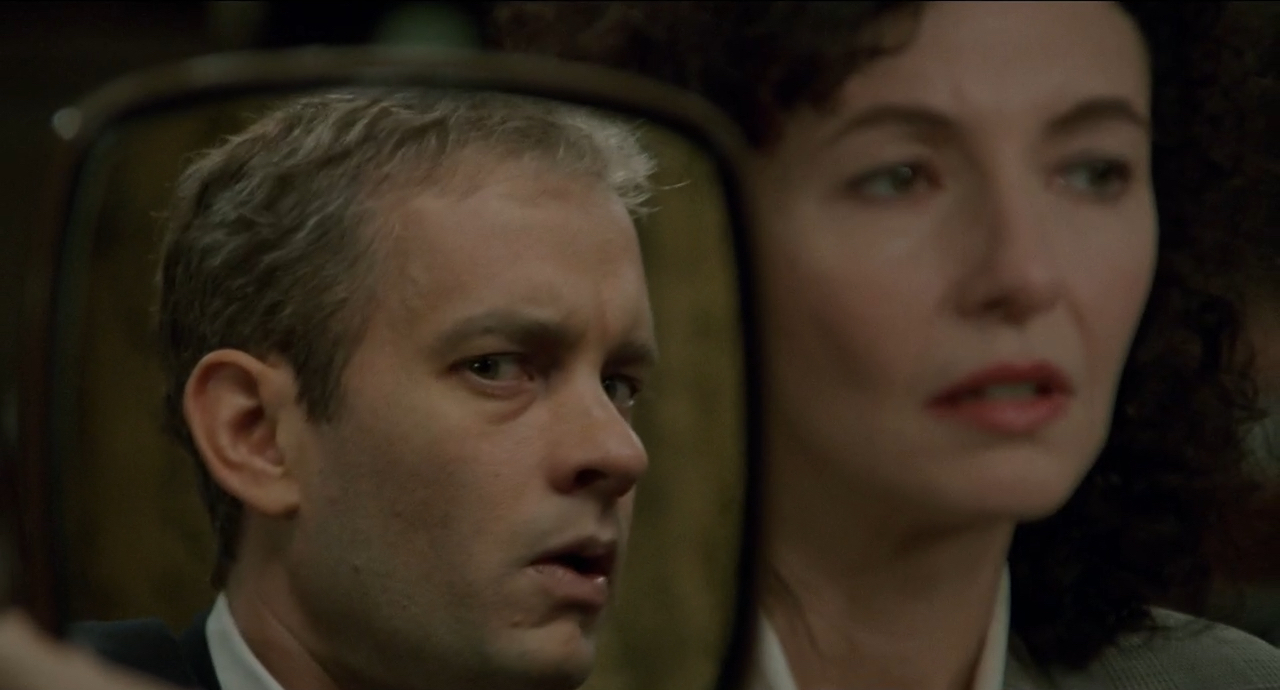

Mike Leigh thoughtfully constructs a character study of immense nihilism here, bleakly considering a tragic figure so absorbed in his own solipsistic perspective that healthy relationships are virtually impossible. It is a tonally tricky line to walk, as Naked’s screenplay is also wryly funny in its dark, comical musings. Like Johnny’s victims, we too find ourselves drawn to his thorny charisma, which constantly rises to the surface of David Thewlis’ bitter, verbose performance. Even when asked by a sympathetic stranger if he has a home to go to, there is a sardonic poeticism to his response, expressing an eternal, restless instability.

“I’ve got infinite number of places to go, the problem is where to stay.”

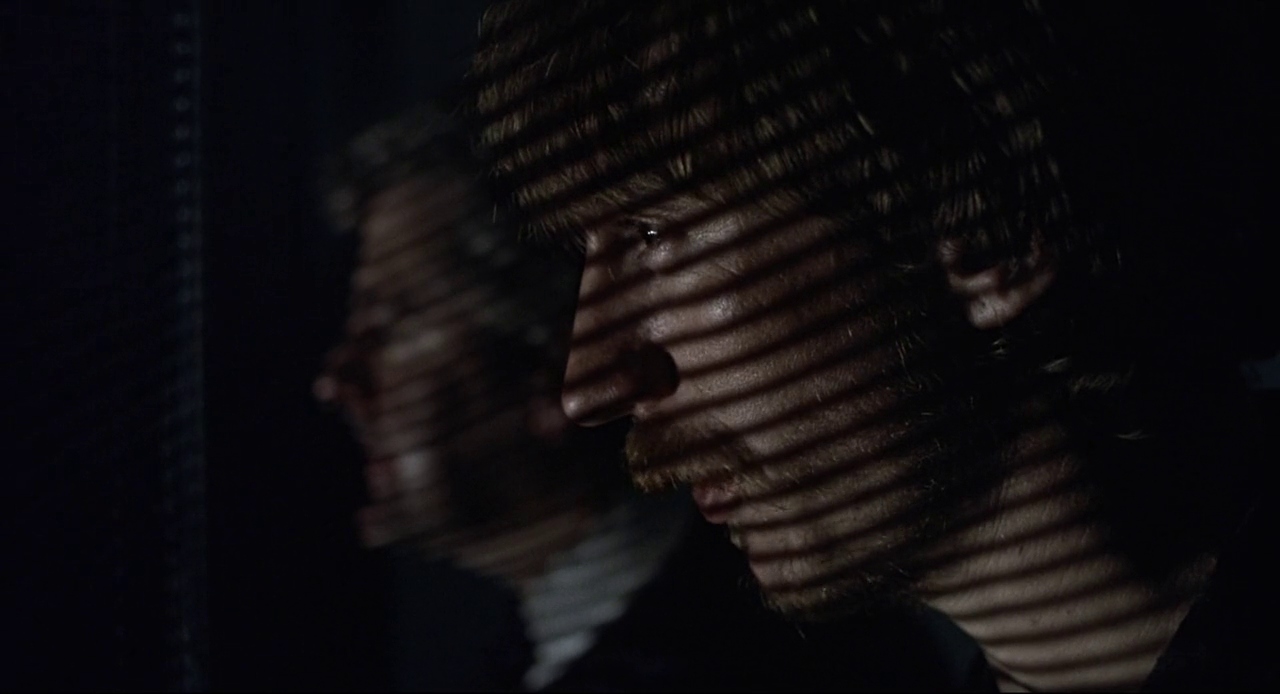

All attempts to cut through the irony and draw some sincerity out of Johnny are fruitless, as he proves himself to be as equally skilled at deflecting as he is attacking others. To those perceptive enough to see past the smartass façade though, his tortured depravity is evident. Leigh’s decision to open the film with what may be Johnny’s most wretched act exposes that side of him right away too, running a handheld camera down a dark alleyway to find him raping a clearly distressed woman.

Realising the need to lay low for a while, Johnny departs his hometown of Manchester for East London where his ex-girlfriend Louise now lives, and makes himself comfortable. There, he meets her junkie flatmate Sophie, who he casts an immediate spell over and starts a relationship with before Louise can even get home from work. The strangers he torments throughout Naked may suffer sharp blows to their self-esteem and happiness, but most of all our pity is reserved for these unfortunate women who know him on an intimate level, yet still can’t seem to escape his cruel, psychological rampage.

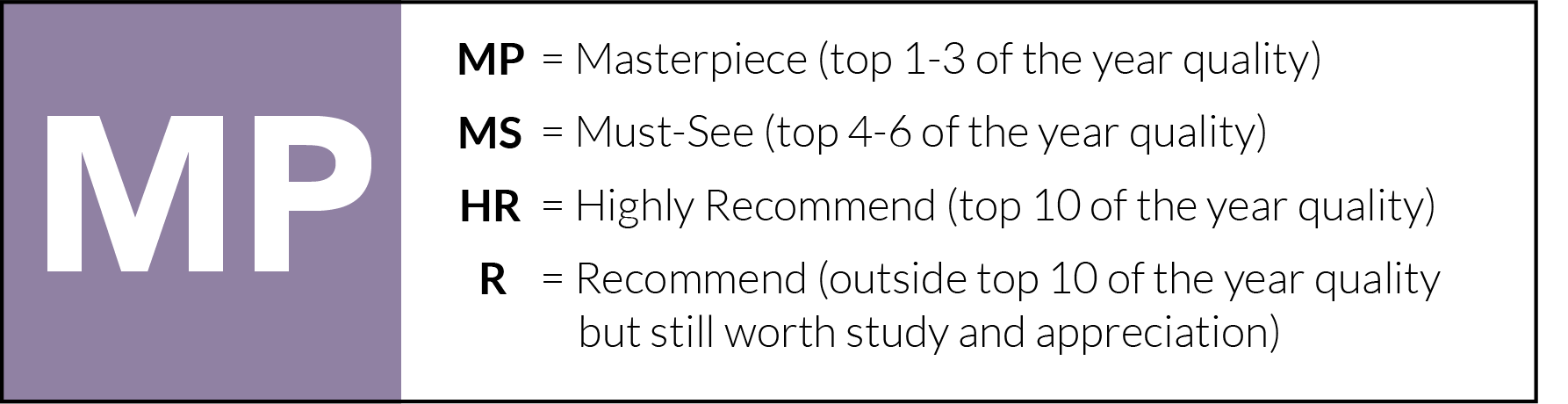

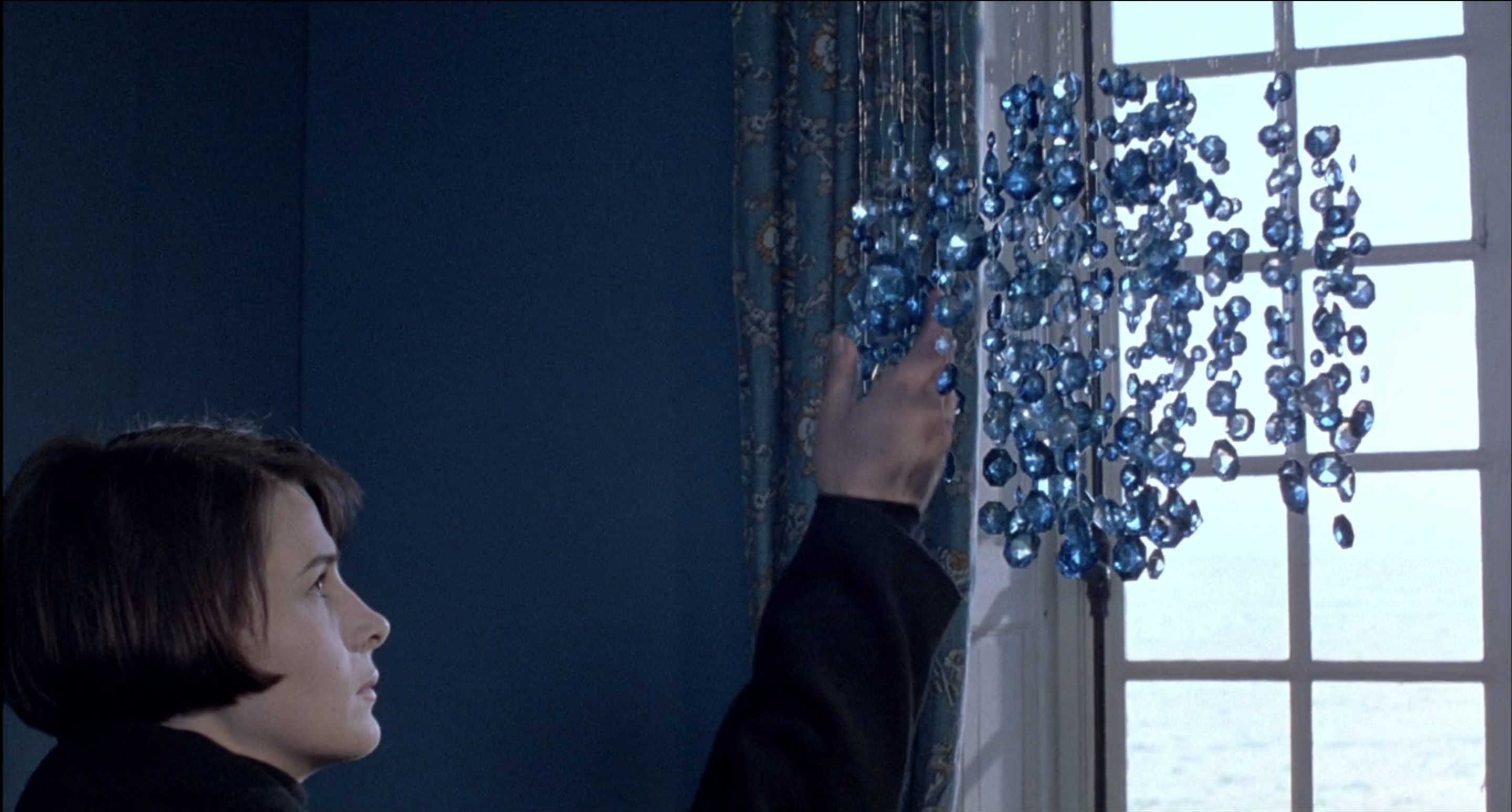

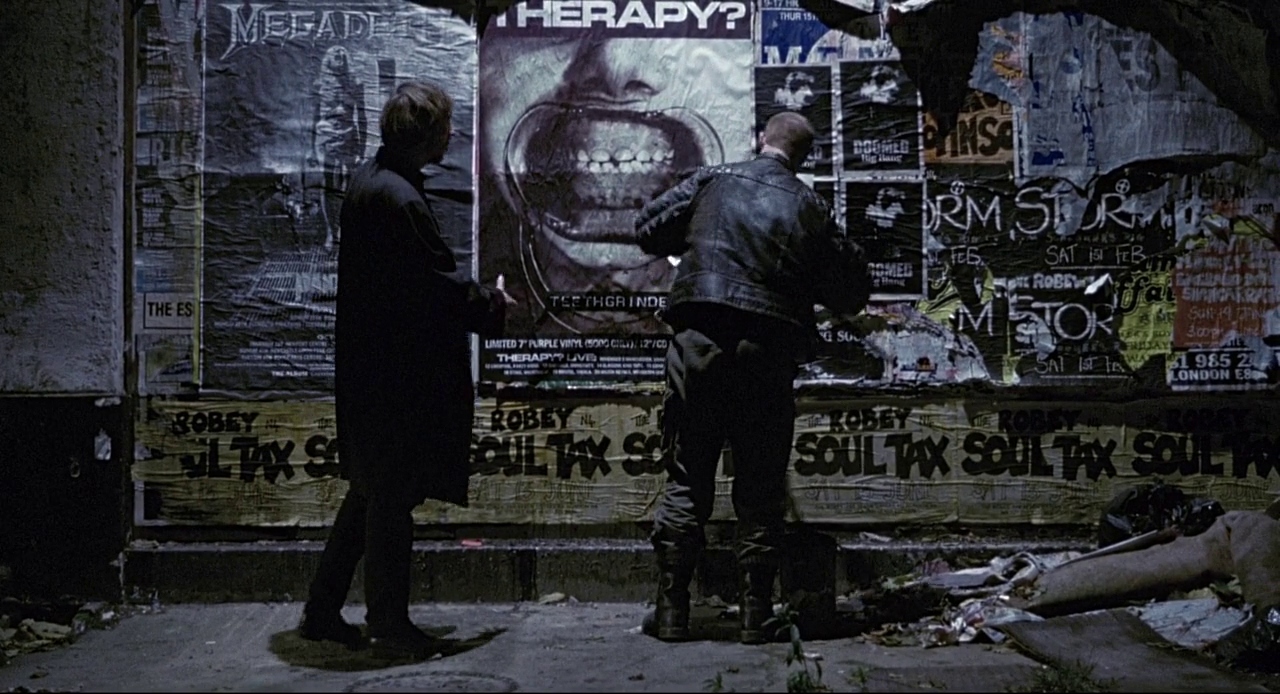

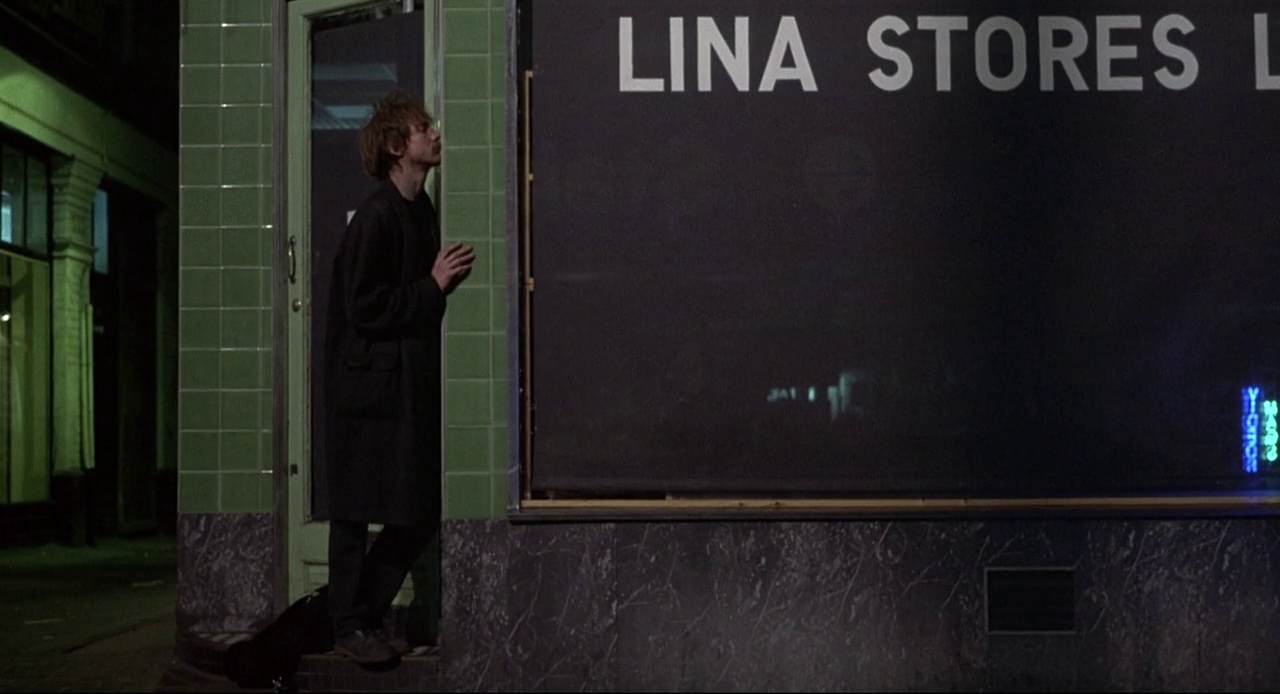

As to whether Johnny is a product of this grim, joyless world or vice versa, Leigh is purposeful in blurring the lines of influence, developing a pervasive, pitch-black production design. It is a remarkable visual motif that is woven into almost every shot, cloaking a dishevelled Thewlis in a dark jumper, overcoat, and boots, and radiating out into tarnished wallpapers, high-end restaurants, and the lifeless décor of Louise’s apartment. It goes beyond the sort of low-key lighting that cinematographer Gordon Willis would innovate in the 1970s, though as he saunters past London’s piercing neon signs and lingers in silhouettes for entire scenes, it is clearly an accomplishment on that level too. These monochromatic shades are rather infused with the total dilapidation of modern-day London, bordering on apocalyptic as black brick walls crumble and homeless camps light fires beneath dank, damp bridges.

Leigh’s claustrophobic location shooting in urban city streets and apartments firmly place this in the lineage of British neorealism, though with such a painstaking curation of mise-en-scène and firm grounding in mythological archetypes, Naked often verges on transcending these conventions. Especially when it comes to the latter, Johnny’s nomadic wandering between various strange characters bears resemblances to Homer’s Odyssey, which he feels he must condescendingly explain to one shy waitress whose home is filled with Ancient Greek figurines, posters, and books. The Book of Revelations similarly becomes a key text in Johnny’s conspiratorial ramblings about the end times, and given the urban decay surrounding him, perhaps there is some vague truth to this. After all, it isn’t hard to imagine him as a charismatic demagogue in such cataclysmic circumstances, gleefully feeding off the chaos and suffering he generates.

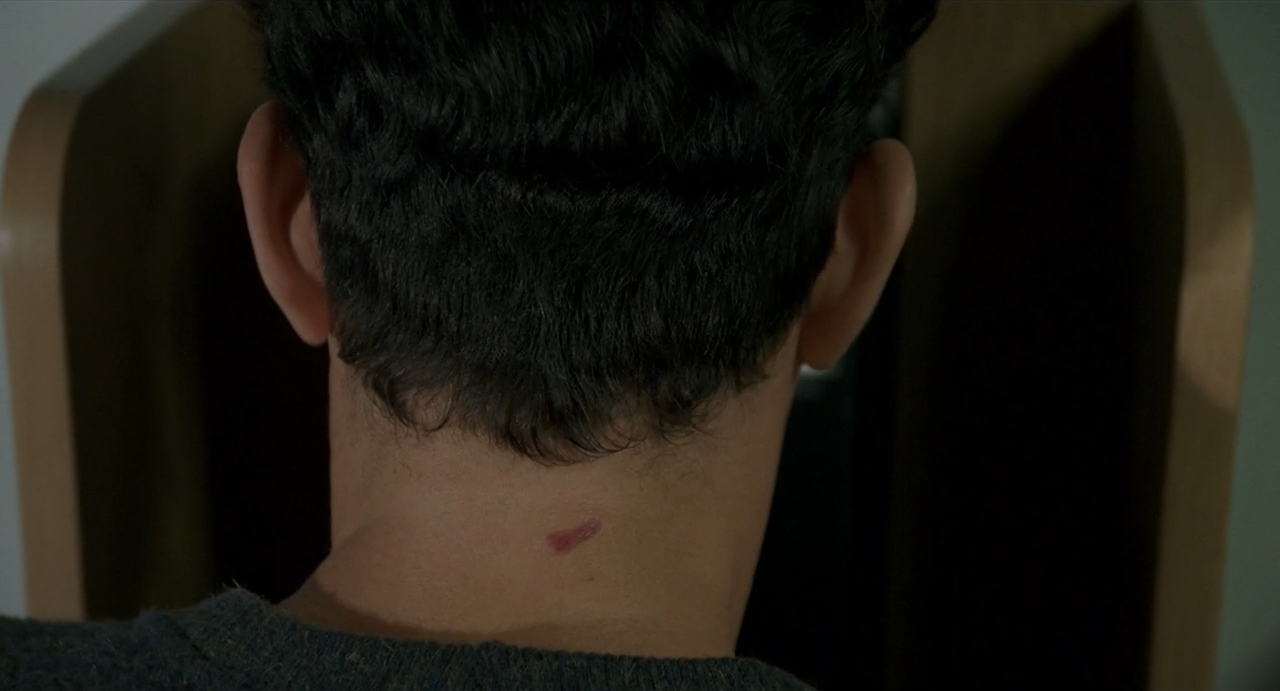

Given the destruction Johnny could potentially wreak in such an elevated position, it is fortunate that he isn’t wealthier or more privileged than he is, but Leigh doesn’t spare us from envisioning that disturbing hypothetical in the character of Jeremy, Louise’s yuppie landlord. He is introduced in extreme contrast to Johnny, visually surrounded by pure white tones, though there is some formal weakness when these disappear and never return.

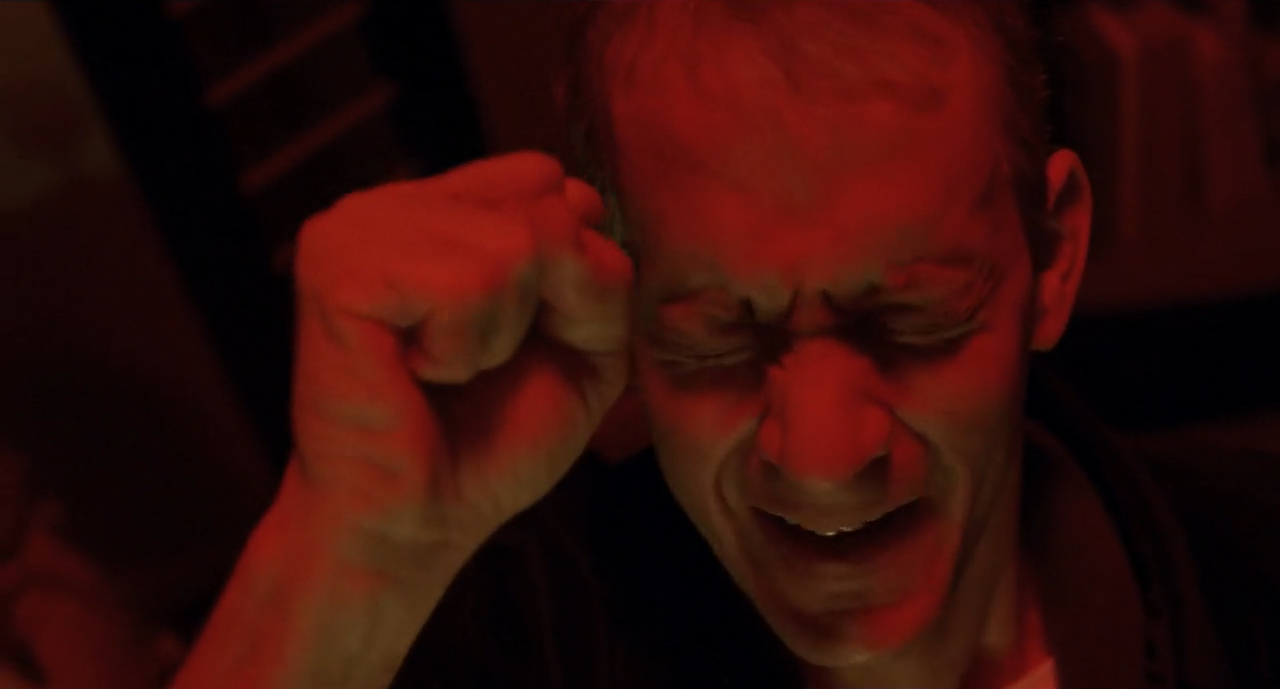

It would be tough to imagine anyone in this world more despicable than our main character, but Jeremy is viciously psychopathic on a level that rivals Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. Where Johnny lords his intelligence over others, Jeremy violently asserts his privilege over all those residing in the flat he owns, even raping his tenant Sophie as a horrific display of ownership. The distorted counterpoint that Greg Cruttwell offers to Thewlis in his characterisation may be firm, yet it is not always relevant in its broader purpose, lacking the depth which makes Johnny such a compelling subject.

This wouldn’t be nearly as rich a character study if we didn’t believe that redemption was in the realm of possibility for this amoral vagrant, though Leigh deals this hope out sparingly, only building it to a peak when a beaten Johnny comes crawling back to Louise and instigates a gentle reconciliation. Their quiet rendition of the folk song ‘Take Me Back to Manchester When It’s Raining’ as they wearily lie down together may be the closest he ever gets to an honest display of emotion in the entire film, revealing a nostalgic connection we never believed him capable of making. There is evidently a past here that holds the two ex-lovers to each other, and it may be all they have left in this crumbling world.

No, it isn’t that redemption isn’t available to Johnny in Naked – it is that even when Louise graciously offers to move back to Manchester with him, he is still governed by a deep, irrational impulse to keep lashing out. He is wounded, and therefore everyone around him must be as well. As soon as the house is empty, he scrounges up all the money he can find and limps off down the street. Andrew Dickson’s propulsive score of harp and cellos urges him forward in this long, unbroken tracking shot, though his destination remains just as much a mystery now as any other point in the film. For all his intelligence, Johnny simply does not possess the self-awareness to break free of the darkness that consumes his sharp-witted mind and vulnerable soul. Instead, it must become an infectious disease to be spread from one place to another, leaving him as its miserable, permanently-afflicted carrier.

Naked is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.