Chantal Akerman | 3hr 18min

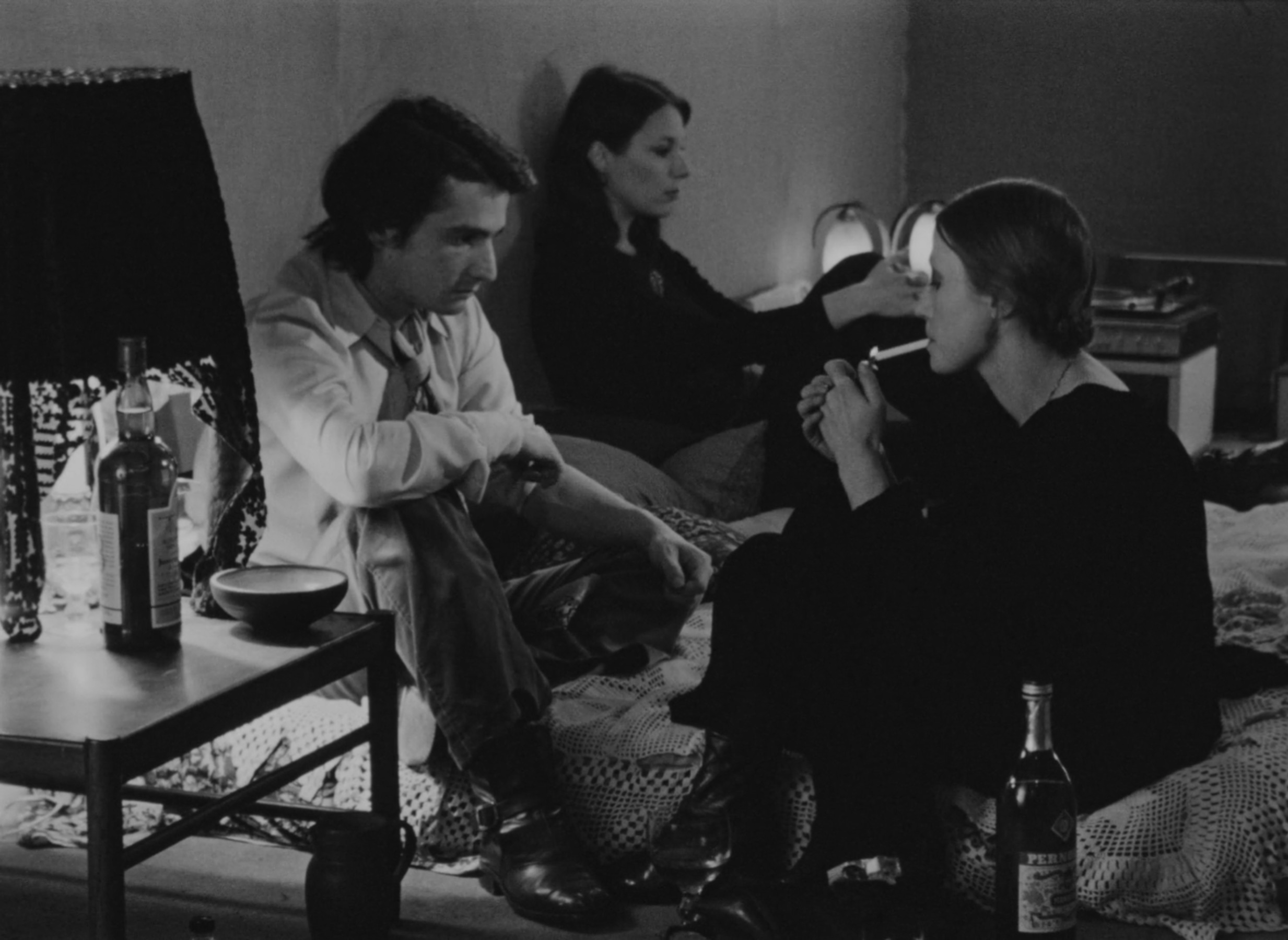

When Jeanne Dielman stops by her son Sylvain’s room to wish him good night at the end of each monotonous day, she has what may be the deepest conversations of her life – not that her standard is terribly high. Her mind is a clockwork contraption that sees no value in abstract discussion or personal growth, but which rather dedicates itself to a single, methodical task at a time, maintaining a stable household for the benefit of her offspring. She is a Sisyphus for the modern age, each day pushing that boulder up the mountain as she polishes shoes, folds clothes, and cooks dinner, only to find herself starting all over again the following morning.

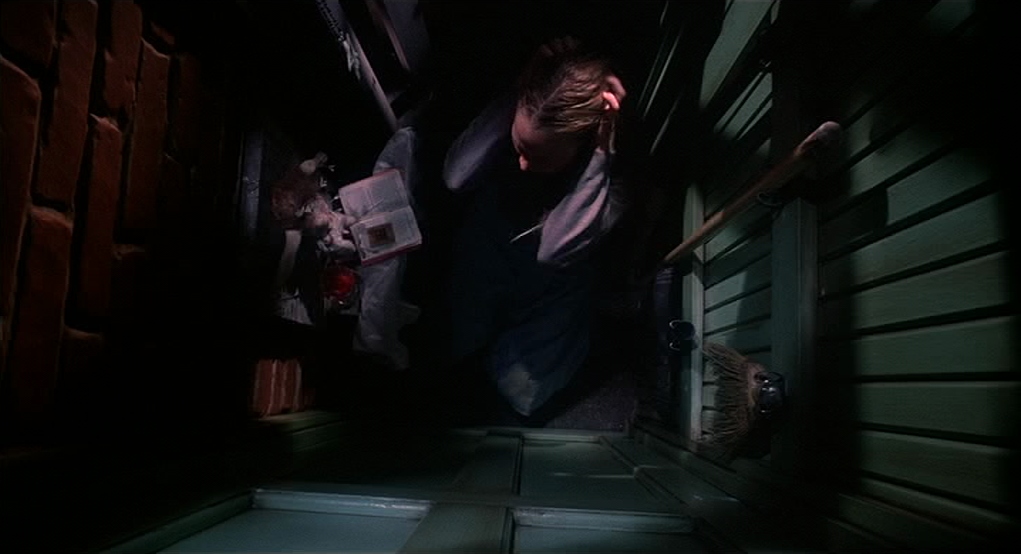

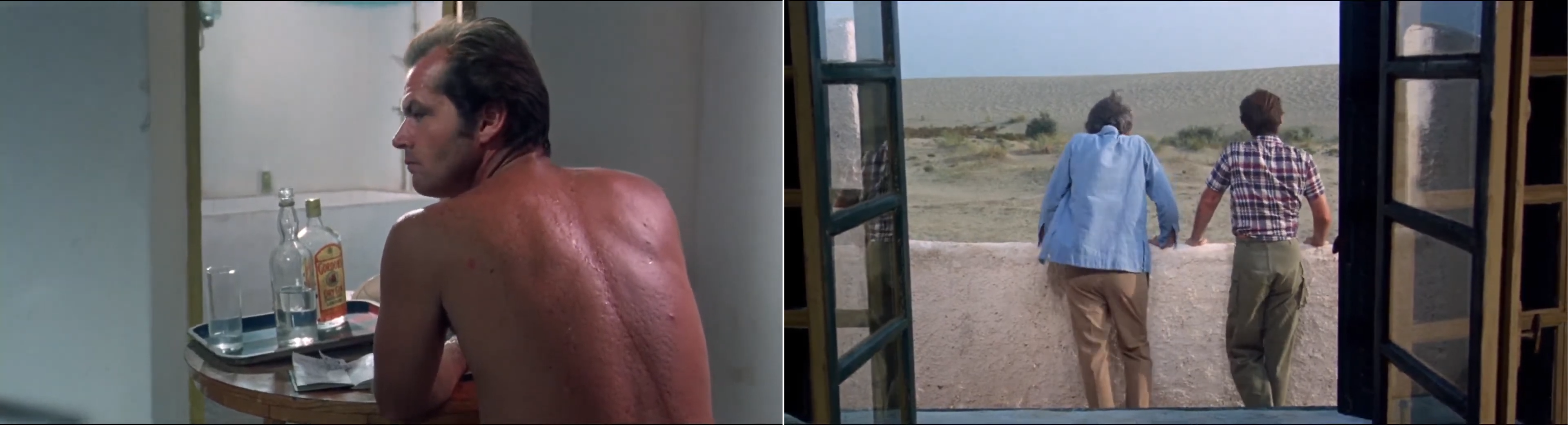

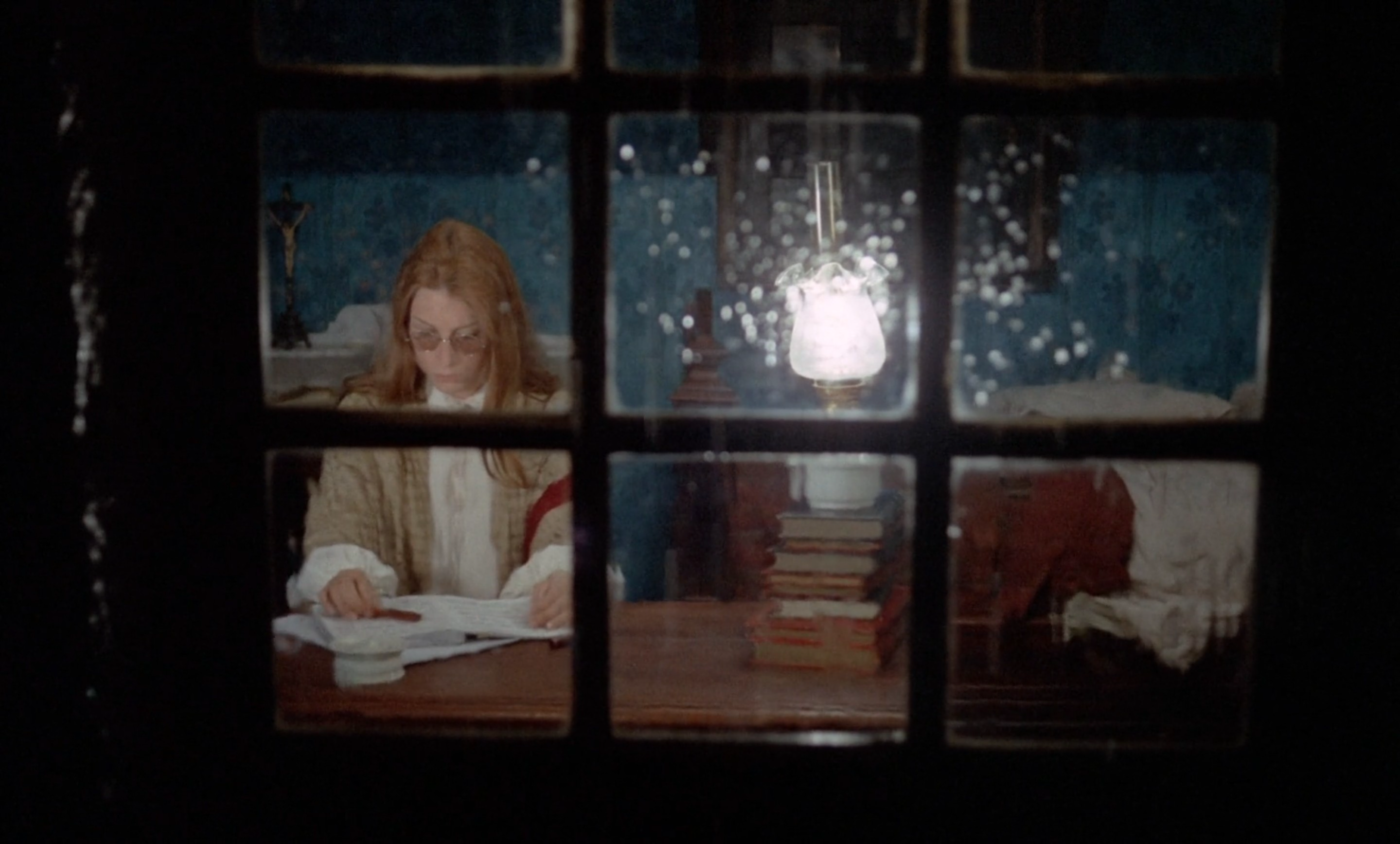

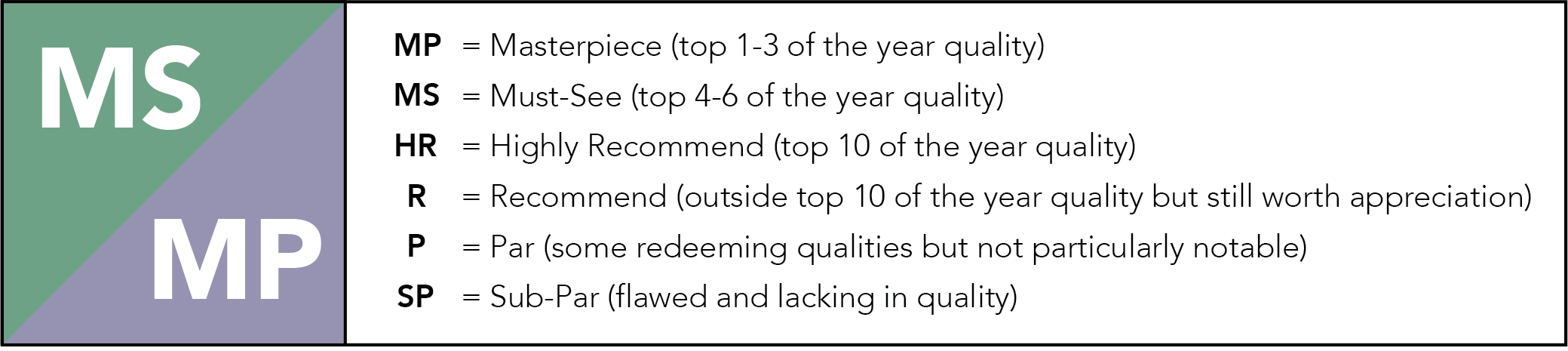

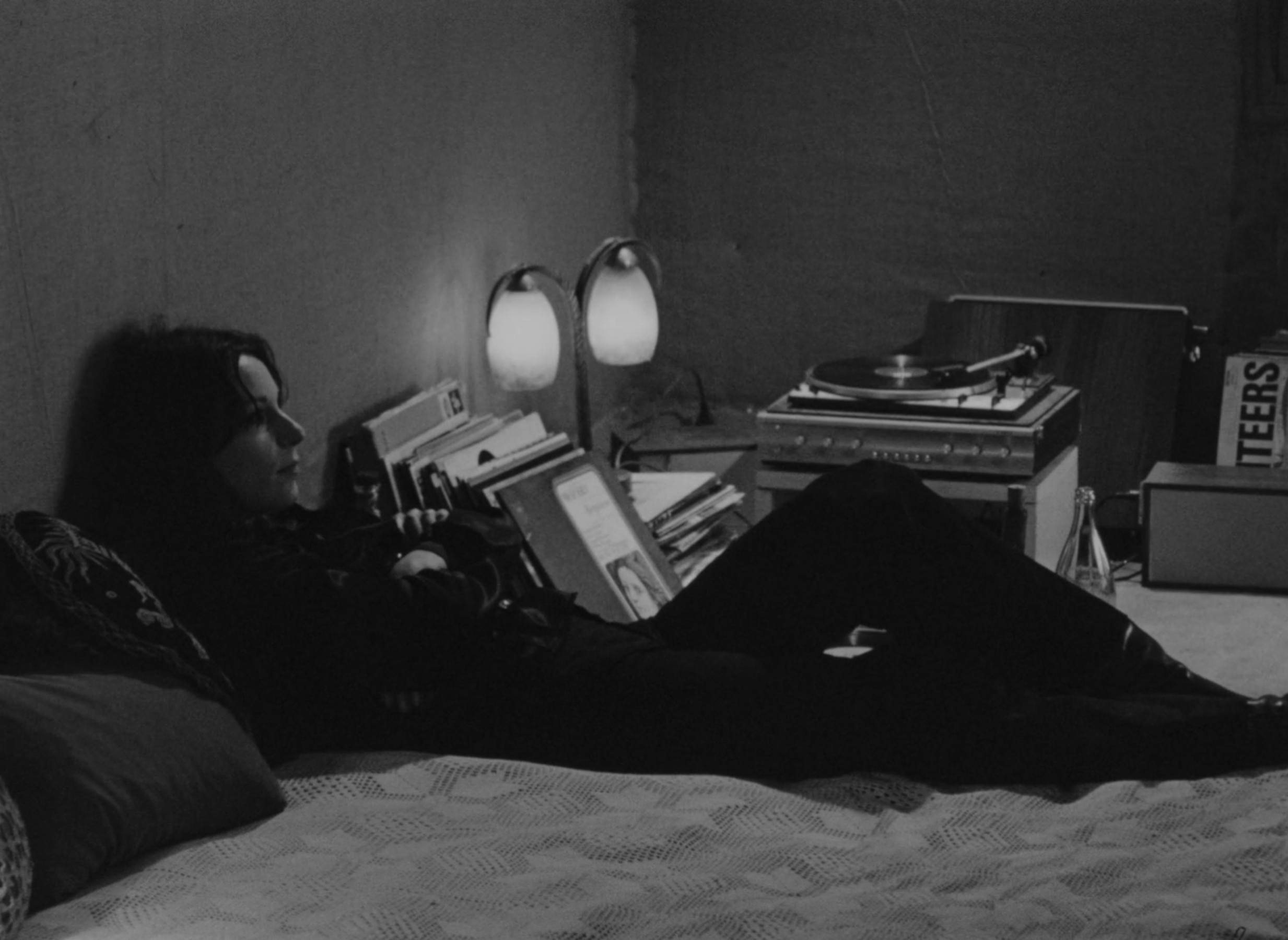

Despite remaining largely ignorant to his mother’s endless toil, Sylvain is the sole stimulus for introspection in Jeanne’s life, gently piercing her insular, middle-class bubble. “You’re always reading, just like your father,” the widow remarks the first night we join them, prompting him to ask about the early days of their relationship. “I didn’t know if I wanted to marry, but that’s what people did,” she ponders, dispassionately reflecting that “sleeping with him was just a detail” like any other in her meticulous daily routine. This comes as no surprise to us, of course. Every afternoon a different male client visits her apartment to pay for sex, and although Chantal Akerman usually cuts away from the act, it evidently unfolds with about as much excitement as making the bed or washing dishes.

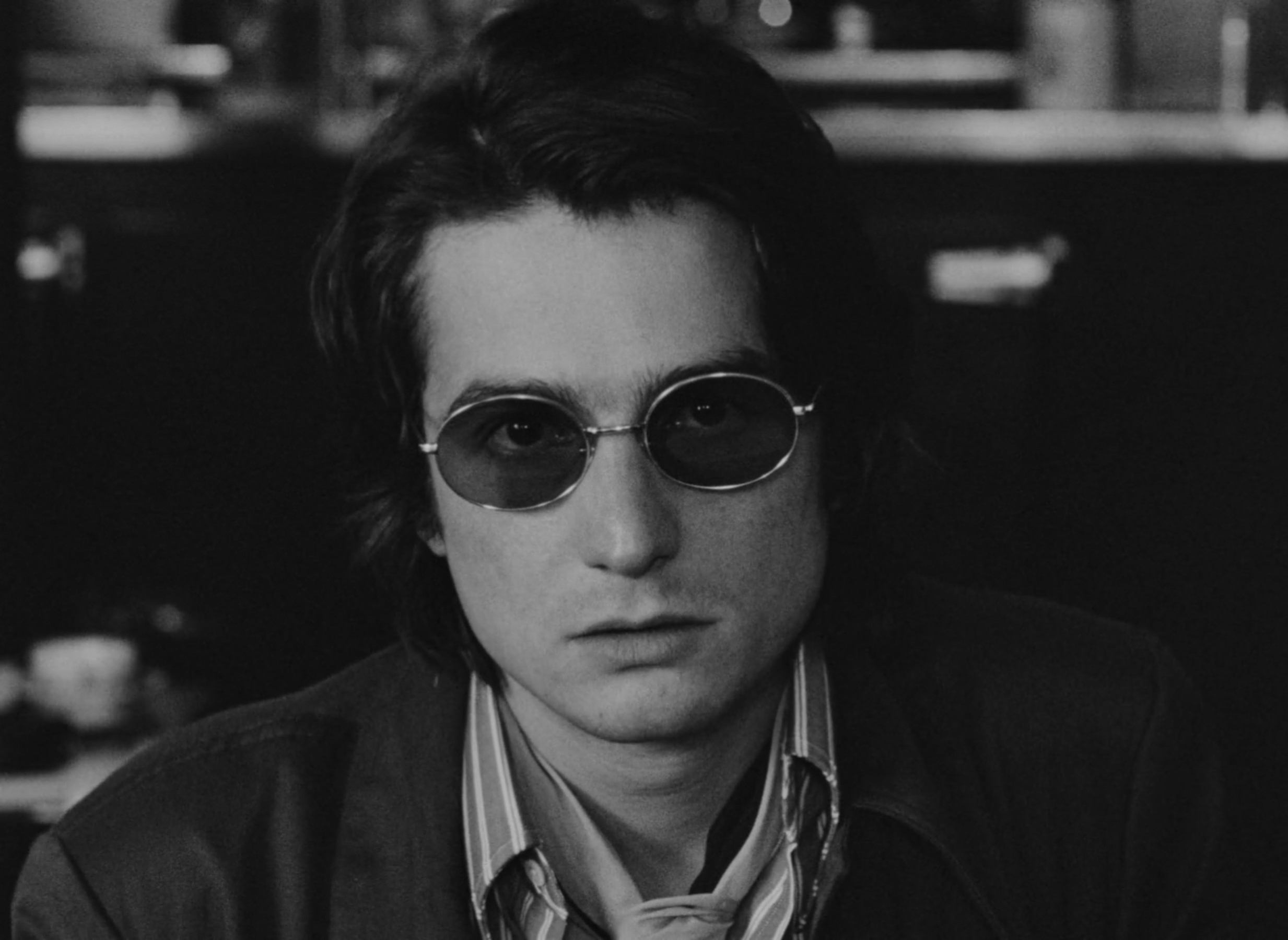

On the second night, Sylvain’s topic of choice turns to his friend Yan, whose experiences with dating have sparked a deliberation on the nature of sex.

“He says a man’s penis is like a sword. The deeper you thrust it in, the better. But I thought, ‘A sword hurts.’ He said, ‘True, but it’s like fire.’ But then where’s the pleasure?”

Jeanne is not nearly as eloquent as her son, but her dismissive response nevertheless articulates the sexual insecurity she has been stifling for years. Sylvain’s confession that he hated his father upon learning about these bodily functions as a ten-year-old verbalises that Freudian relationship between them too, giving her even greater reason to shy away from the topic despite conforming to its associated gender roles. Sex is a messy, complicated thing, and its distillation down to a simple business transaction allows her to rationalise its functionality beyond childbearing – so anything which endangers the pleasureless system she has built her life upon may very well reach the magnitude of an existential threat.

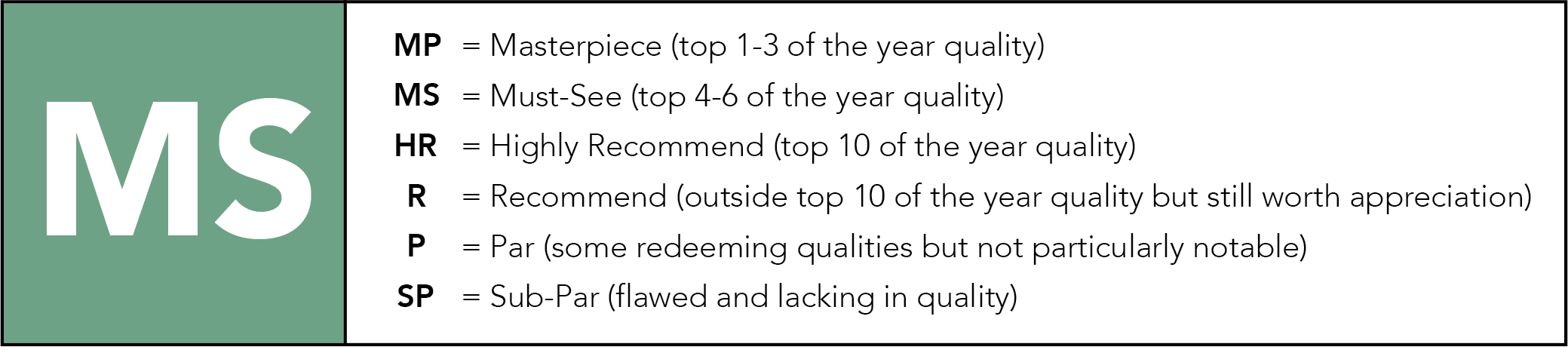

Perhaps the only thing longer than the title Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is the film itself, stretching out over three hours which force us to feel every passing minute. Its selection as the greatest film of all time according to the 2022 Sight and Sound list is no doubt an odd choice, but for those who deny its lack of artistic value, its lofty ranking has ironically proven to be the most common argument against it. Overrated it may be, but Akerman’s slow, laborious study of domestic anxiety is far from a failure, constructing this plotless narrative around rigorous formal patterns before incrementally eroding them with Jeanne’s psychological state.

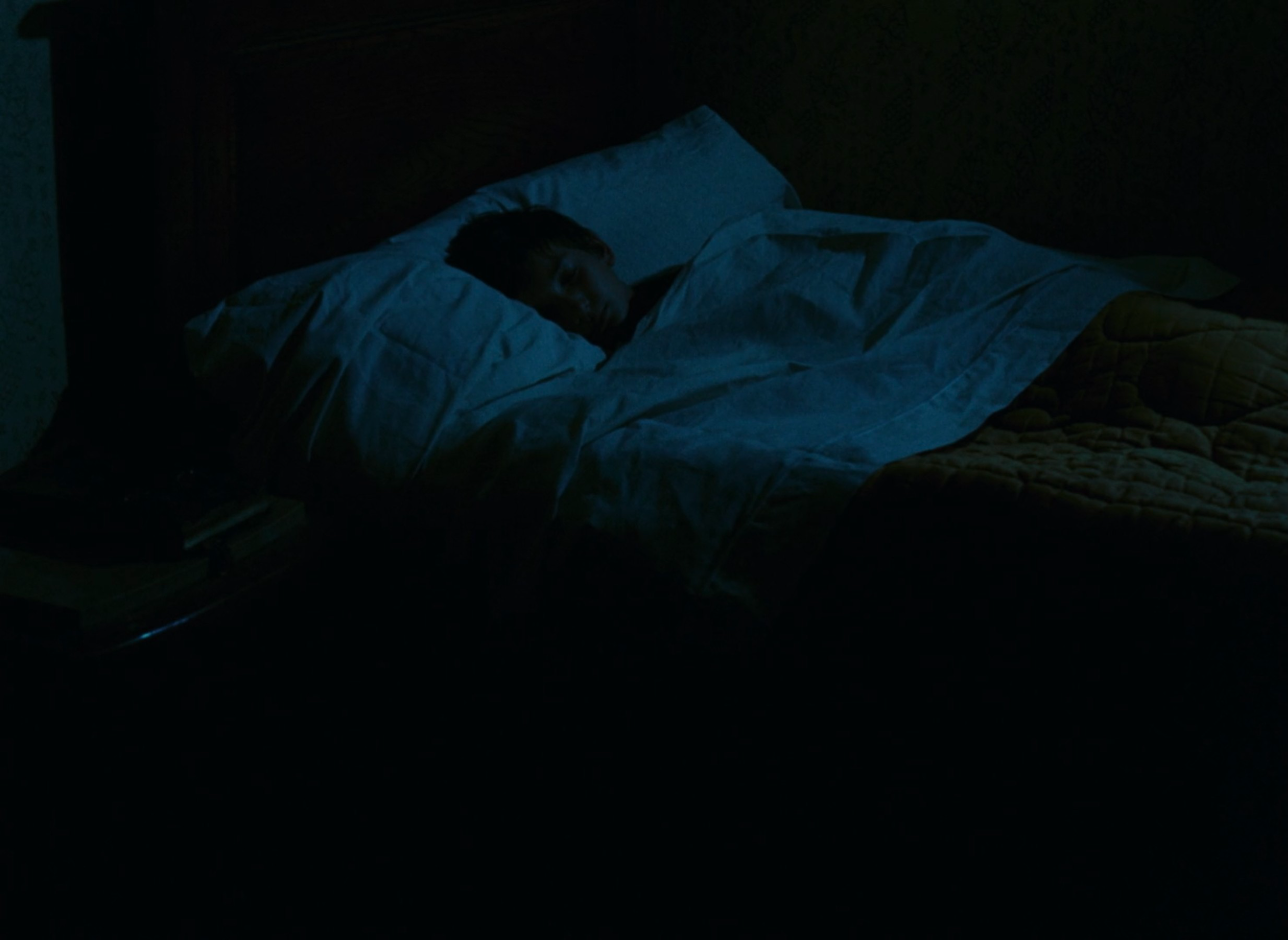

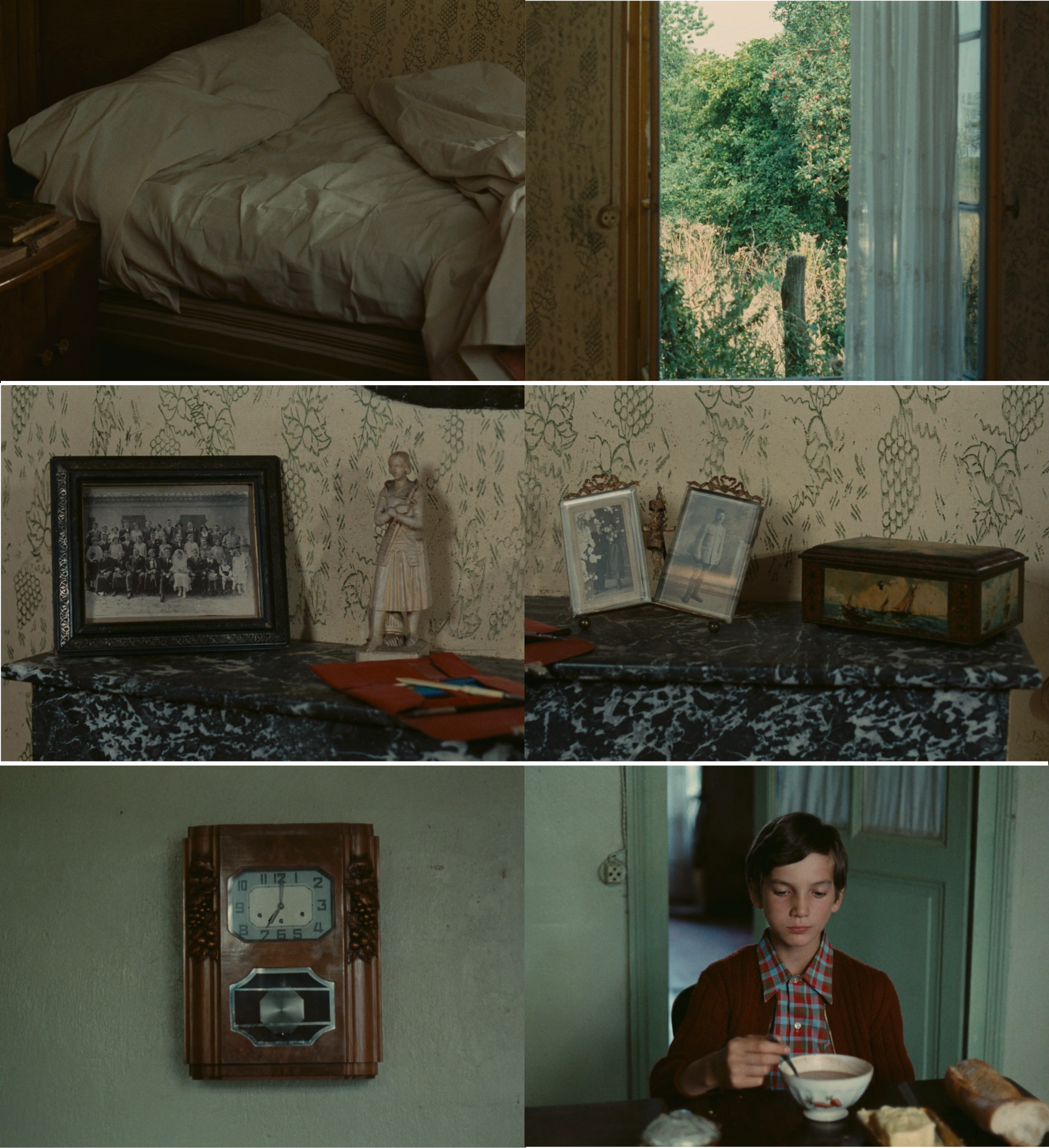

Beginning on the afternoon of the first day and ending on the afternoon of the third, we watch every detail of her routine play out twice, with one major exception. The rendezvous she conducts with three men visiting her apartment mark the opening, midpoint, and conclusion of Jeanne Dielman, each one escalating in psychological impact and rippling out to the rest of her life. The delicate balance which Akerman cultivates in this character study attunes us to her habits, finding peace through meditative, dutiful repetition of familiar actions such as turning off the lights whenever she leaves a room.

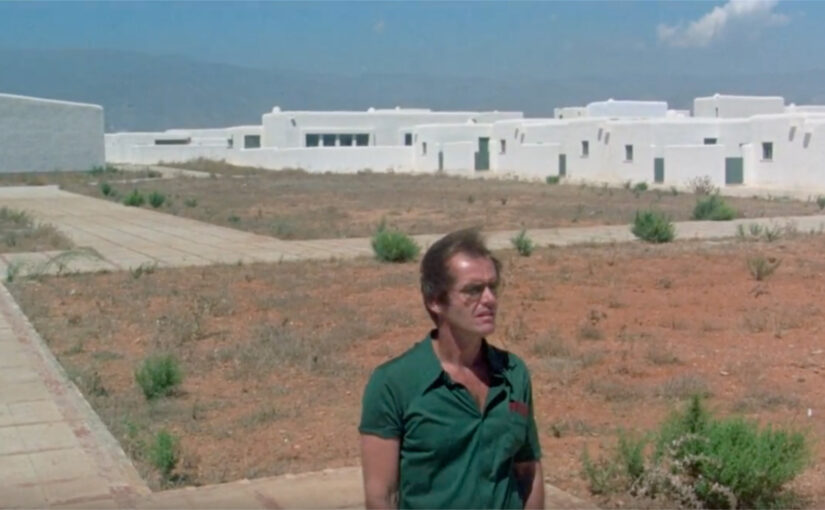

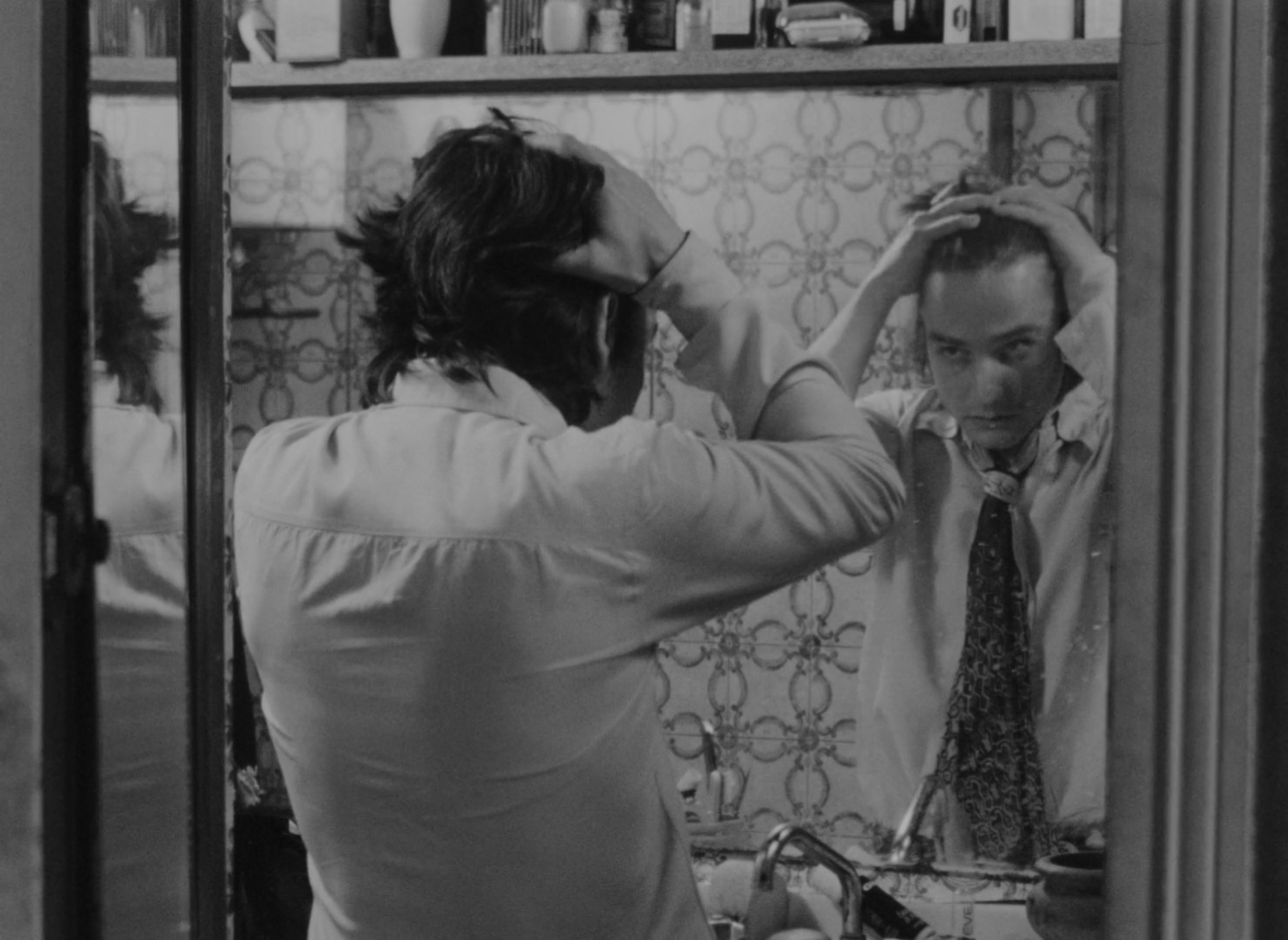

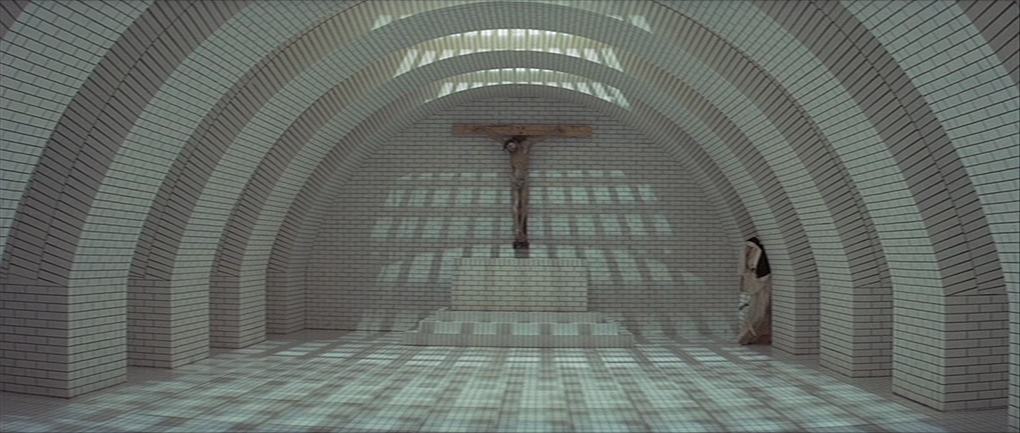

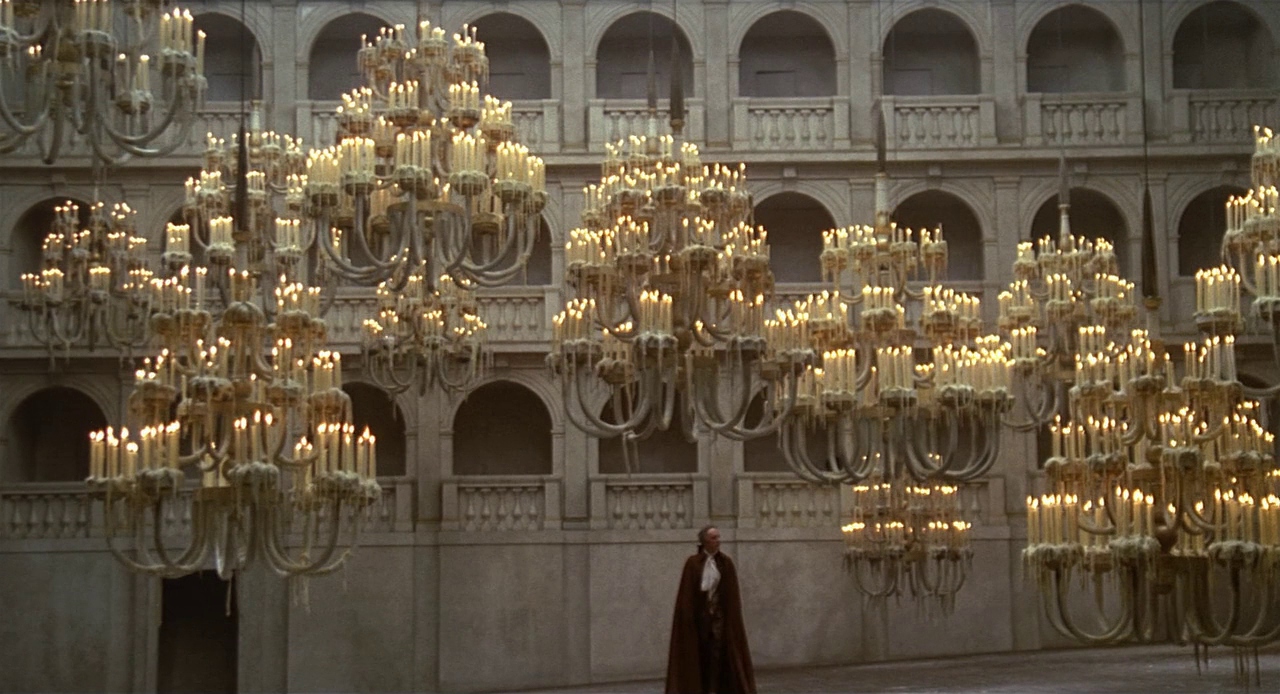

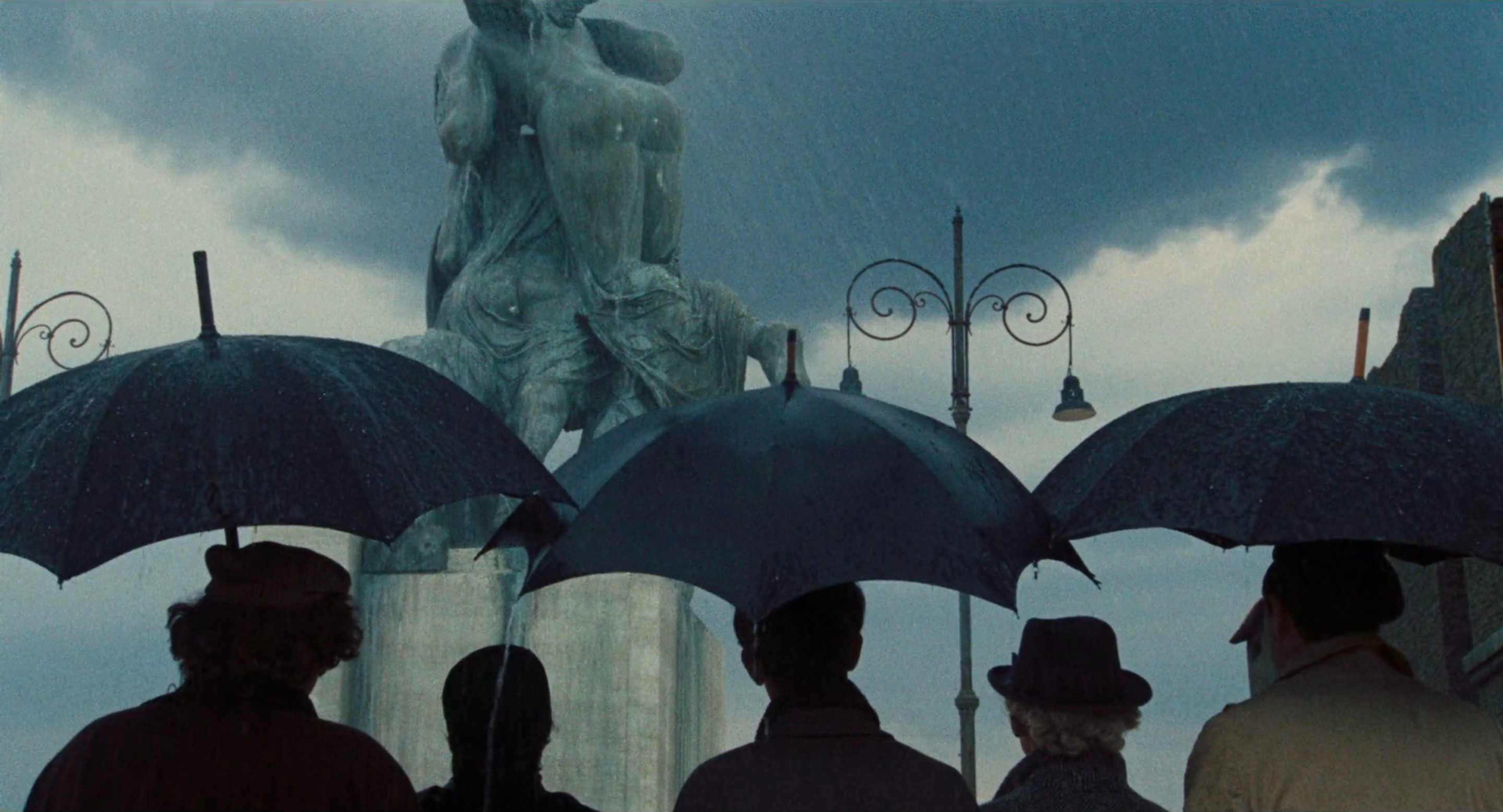

Although Jeanne treats her home like a palace, Akerman’s drab mise-en-scène of beige tiled walls and chequered floors tells another story of soul-sucking mundanity. The film may not possess the compositional precision of Yasujirō Ozu’s domestic dramas, but Akerman is his equal in long, static shots, distantly sitting as a neutral observer while Jeanne’s movements fill the frame and often leave it altogether. The camera primarily sits at square angles relative to whichever room it occupies, rejecting the disorder of diagonal lines and maintaining Jeanne’s systematic harmony in whichever perspective we take. Outside as well, Akerman layers each shot using her full depth of field, tunnelling the sidewalk outside Jeanne’s home between buildings and parked cars, while the green park bench across the road from her apartment building sets a firm boundary between the foreground and background. Of course, there is barely a shot in Jeanne Dielman which Akerman resists calling back to either, ingraining this perfectionist’s strict regimen within the very language of the film.

As a result, the first time Jeanne misses a crucial step in her routine and forgets to flick off the light switch after leaving a room, we are totally thrown. Akerman’s extratextual clarification that it was an orgasm with the second client which instigates this chaos seems a little lazy given that we never see any specific suggestion of it in the text, yet we can at least reach the conclusion that this encounter is somewhat responsible given how soon afterwards the breakdown begins. She has deeply internalised the idea that pleasure is a luxury that women are not allowed to experience, and the slightest breach of that doctrine may very well destabilise the life of tedious self-sacrifice that has been built upon it, setting off a catastrophic domino effect.

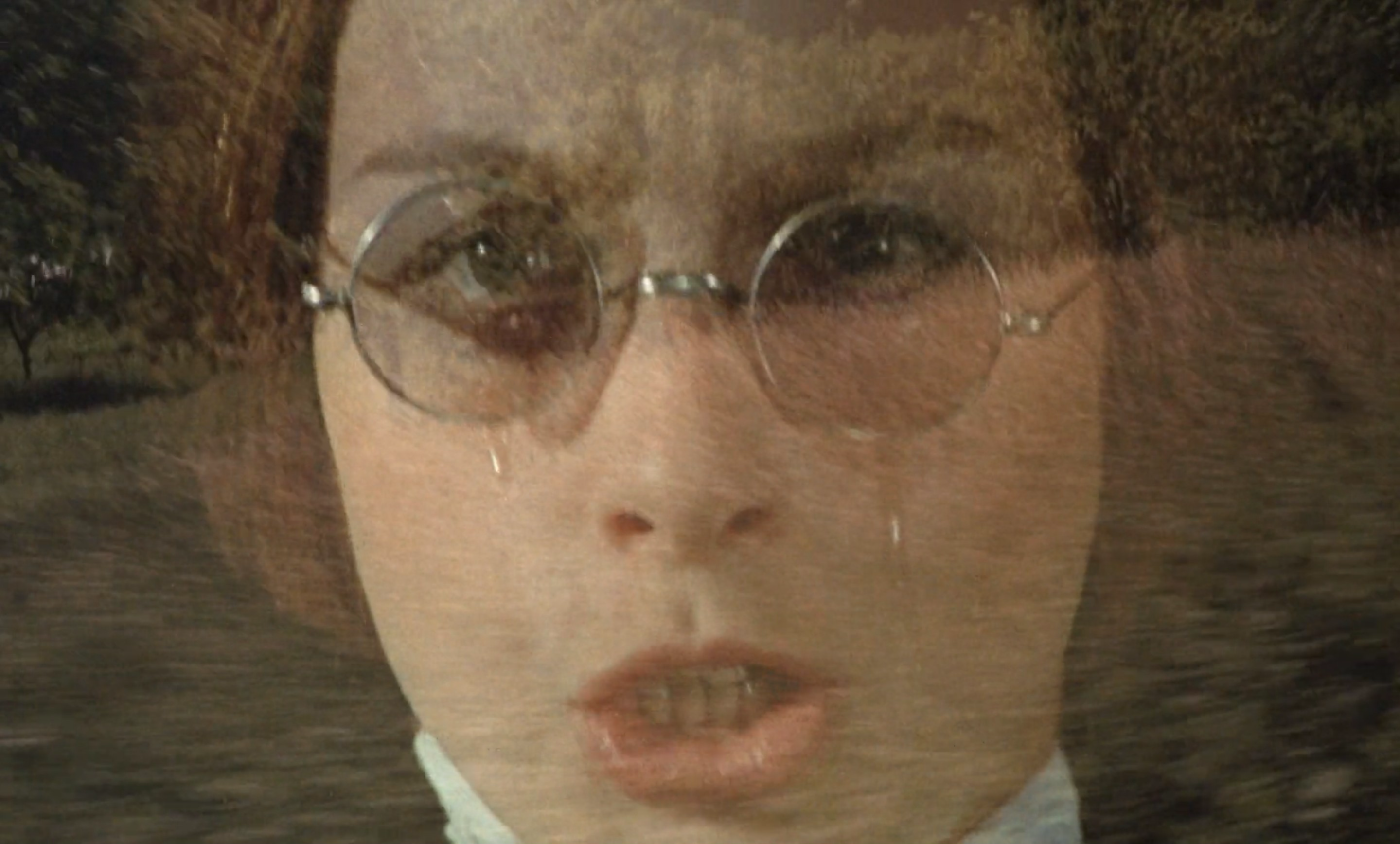

Because Jeanne must return to the bathroom and switch the light off, she accidentally lets the potatoes boil for too long, and is left wandering the house unsure where to place the pot. Eventually sitting down at the kitchen table to peel them, Delphine Seyrig’s performance shifts from mechanical indifference to silent frustration, slicing into the vegetables with harsh, aggressive motions. When Sylvain arrives home, dinner is served late, and his desire to go to bed early rather than head out for their evening walk is promptly rejected.

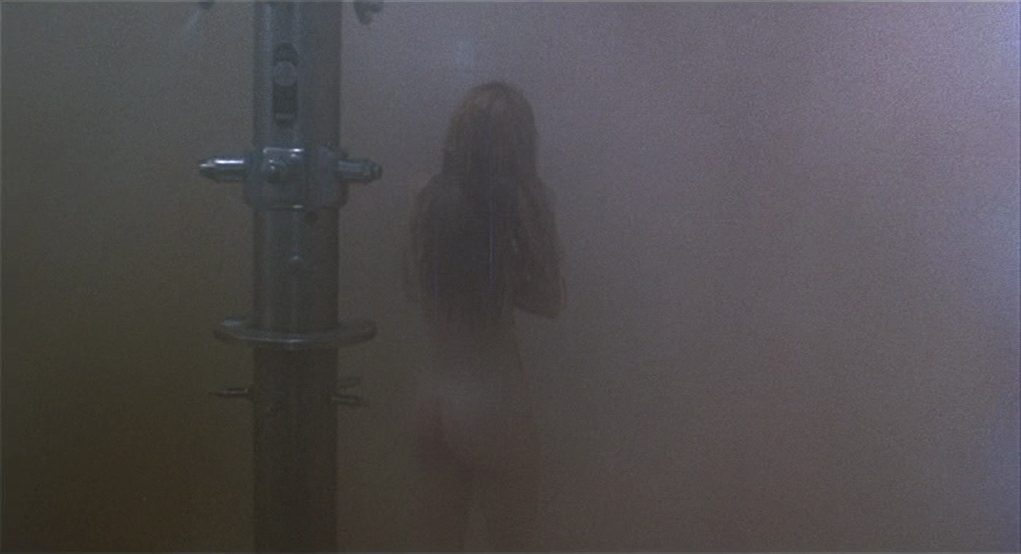

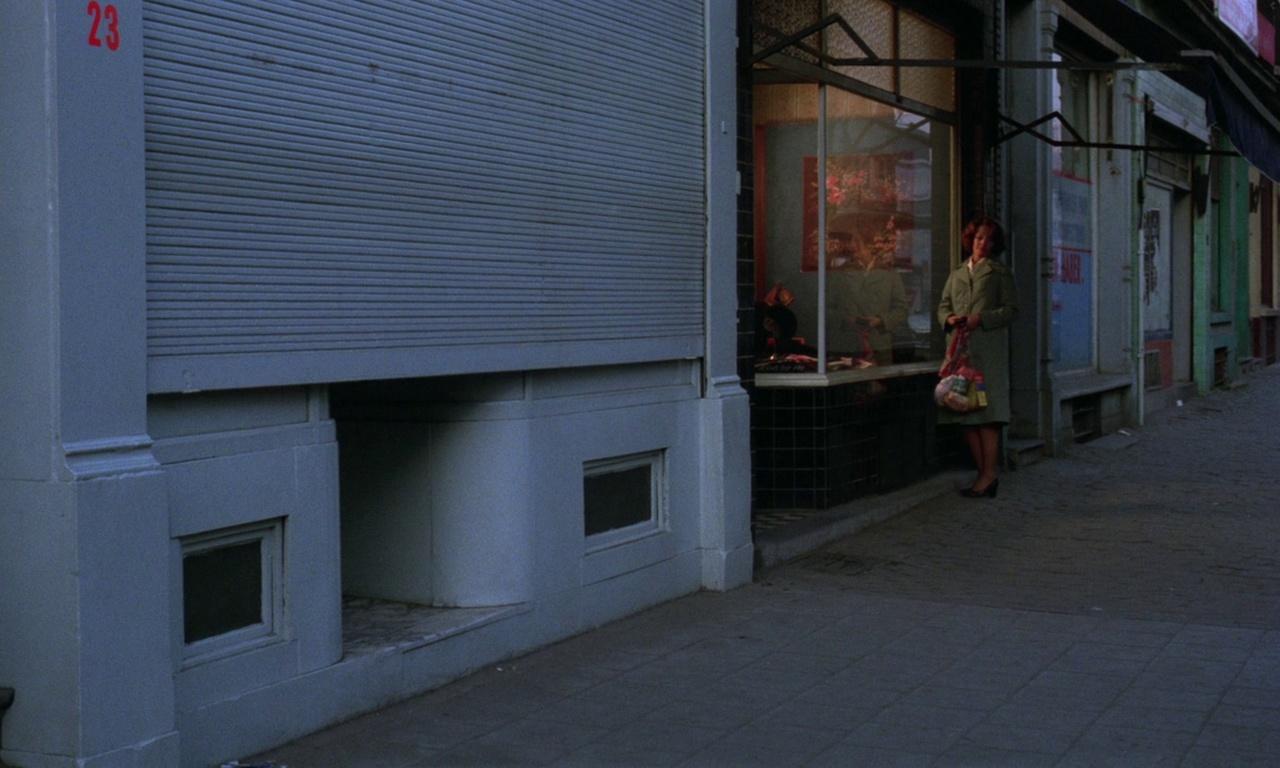

Unfortunately, the start of a new day doesn’t exactly bring relief for Jeanne either. When she polishes Sylvain’s shoes in the morning, her strokes are just a little too forceful, causing her to drop the brush. When she wakes him up, she accidentally turns the light on, before quickly switching it back off in a panic. At the kitchen sink, she rewashes the same dishes several times in a row, unsatisfied with her work. Even when she leaves home to buy groceries, she arrives early at one of her regular shops, and must awkwardly wait for the shutter to be rolled up. This day is even more of a disaster than the one before, leaving Jeanne scrambling to adapt to what may be considered minor inconveniences in anyone else’s life, but which to her are cataclysmic acts of violence escaping her impeccable control.

It is here where Akerman’s recurring shots begin to pay off as well, instilling remarkable form in the disintegration of Jeanne’s strict procedures. In the diner that she visits for lunch each day, she has previously been positioned in the middle of the frame – though now she enters to find a stranger sitting in her usual seat. As a result, she may no longer occupy the centre of this once-balanced composition, but rather the humiliating, undignified seat on its edge.

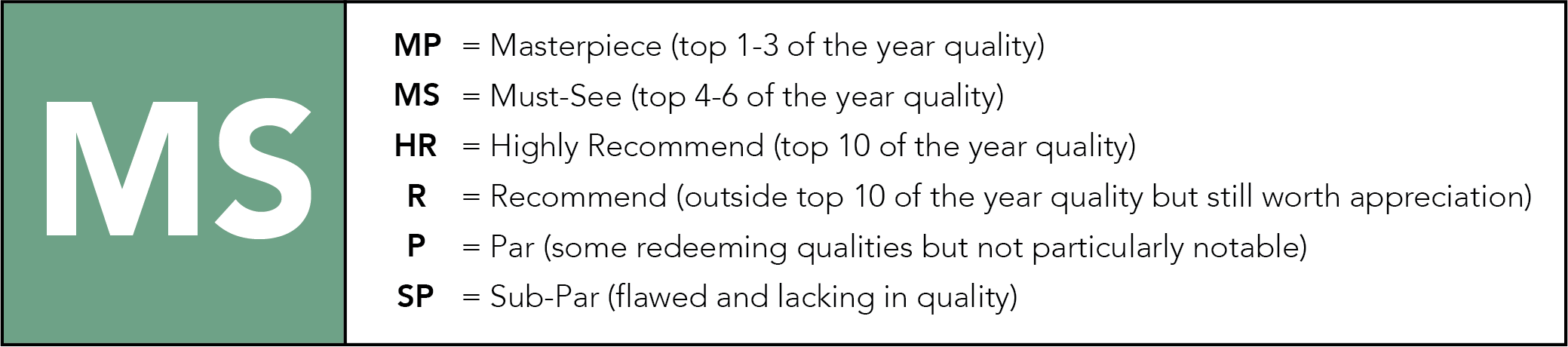

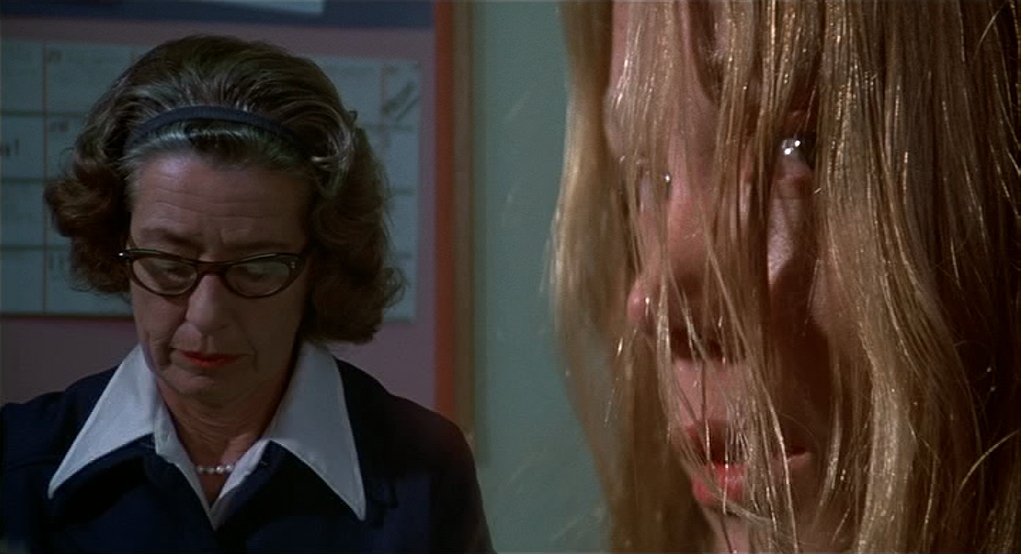

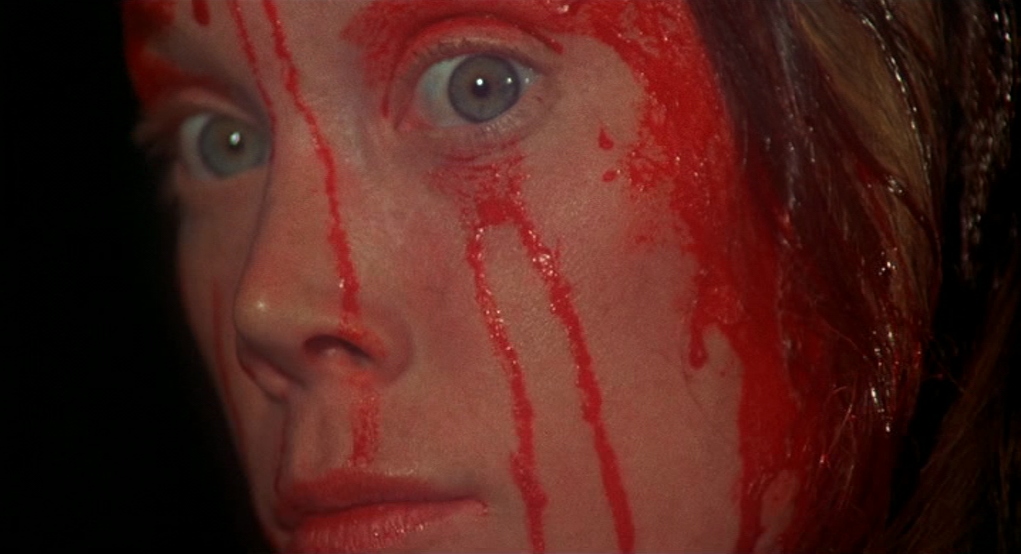

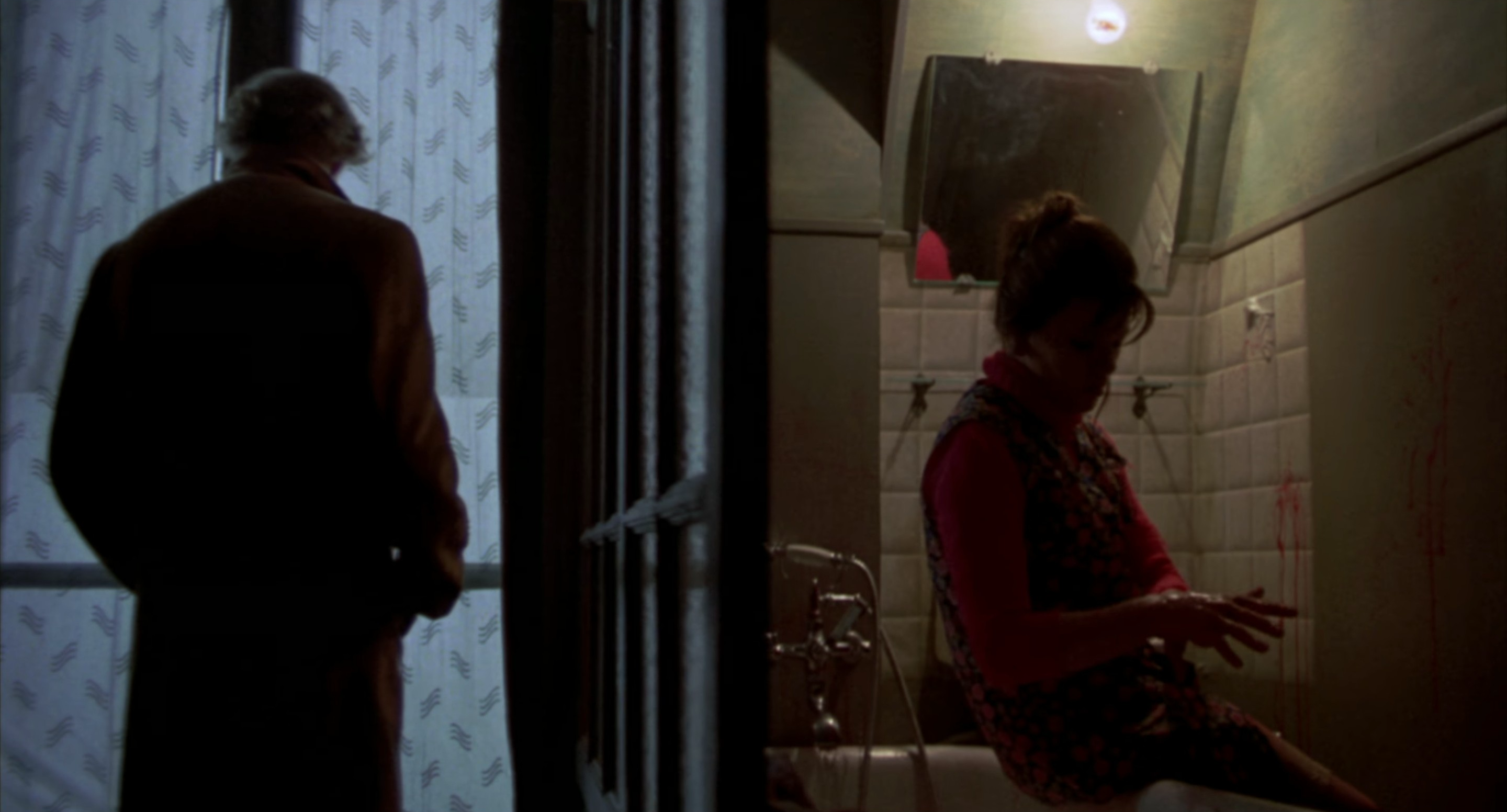

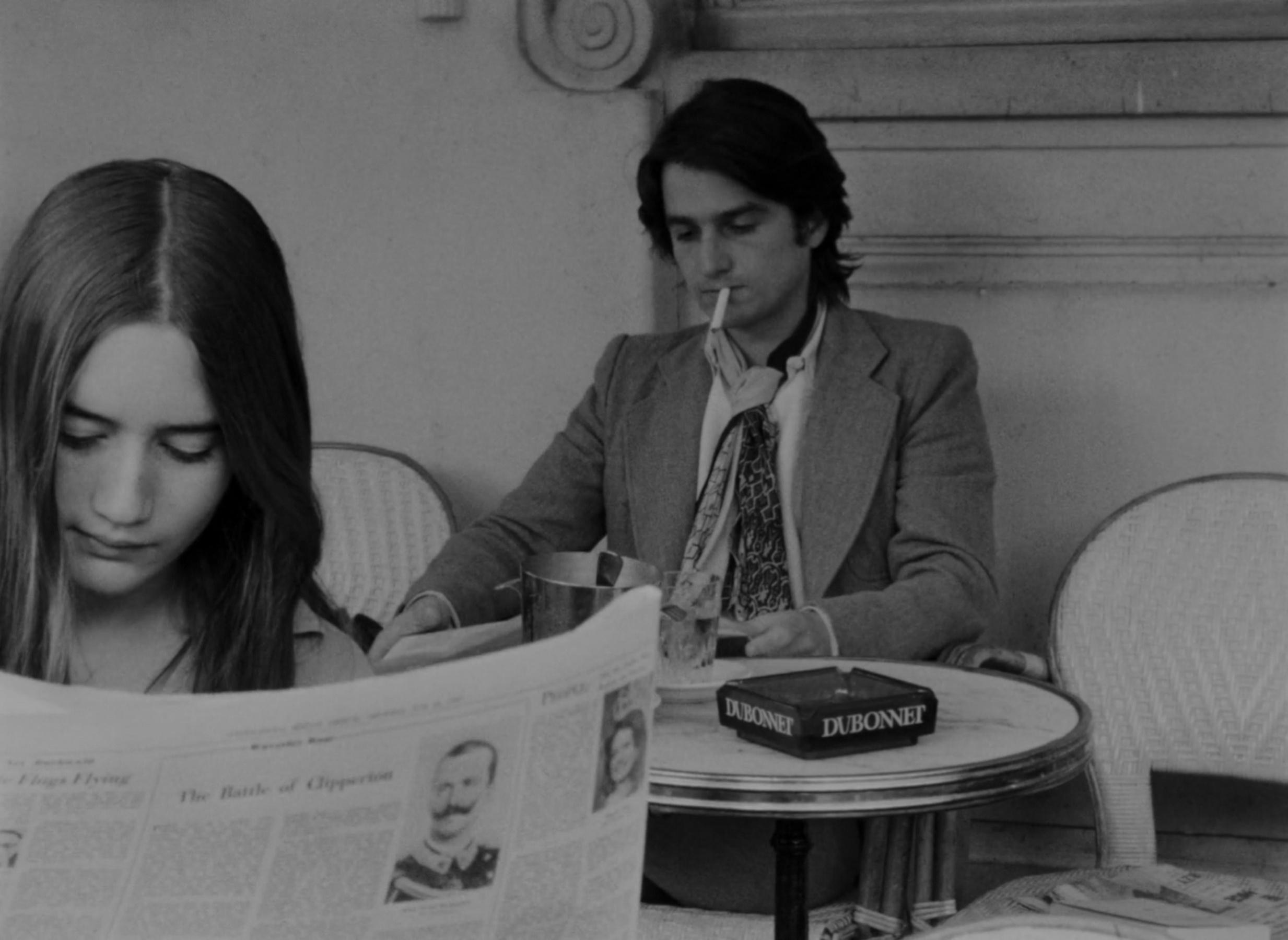

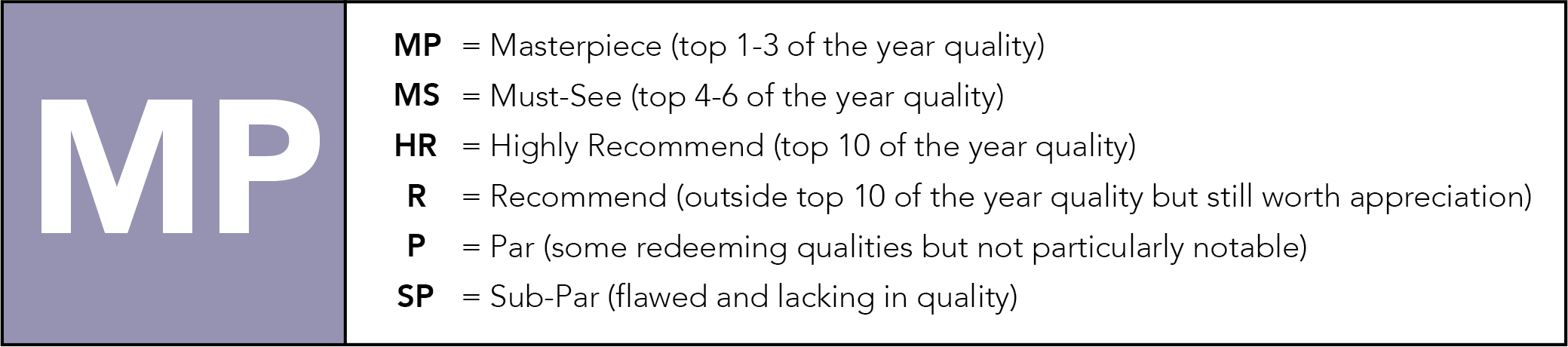

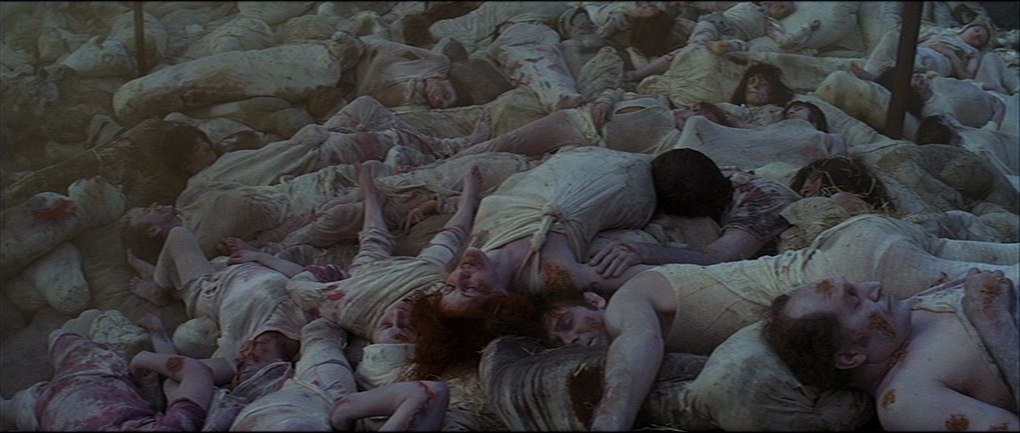

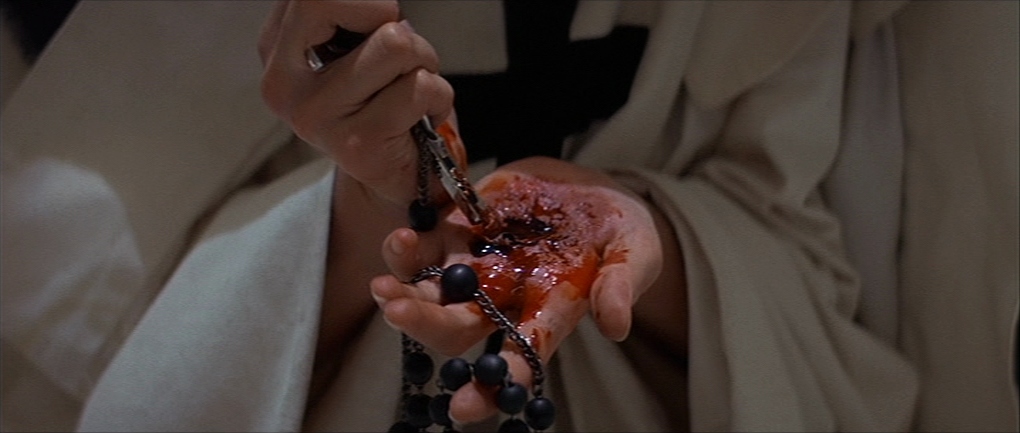

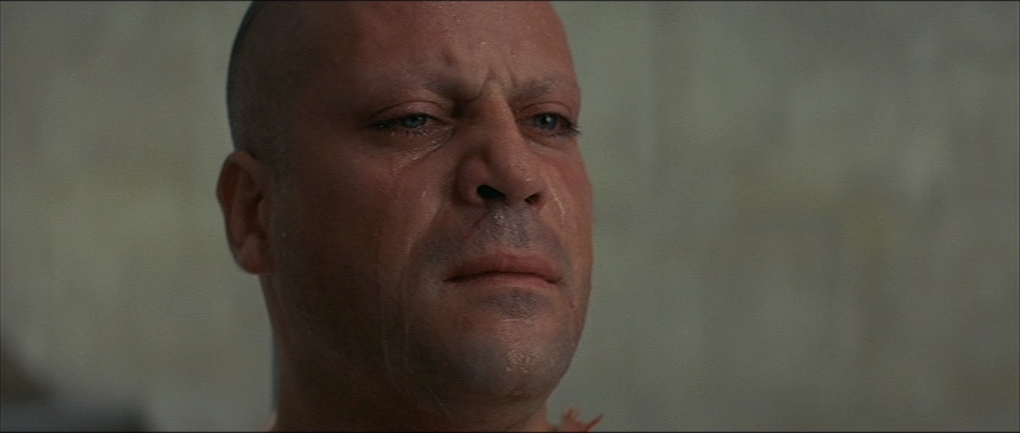

When the culmination of Jeanne’s frustration intersects with the arrival of her third client, Akerman no longer even cuts away from the intercourse as she writhes and struggles beneath him, holding on one of the few standalone shots that isn’t doubled anywhere else. Is this an assault, we wonder, or another orgasm, provoking intense discomfort as she tries to rid herself of this forbidden pleasure? Either way, her reaction is the most visceral we have seen from her at any point – not that it holds this distinction for long. The following shot catches the reverse angle in the dresser mirror, dissociating Jeanne from herself as she rises from the bed, retrieves a pair of scissors, and stabs the man in his throat.

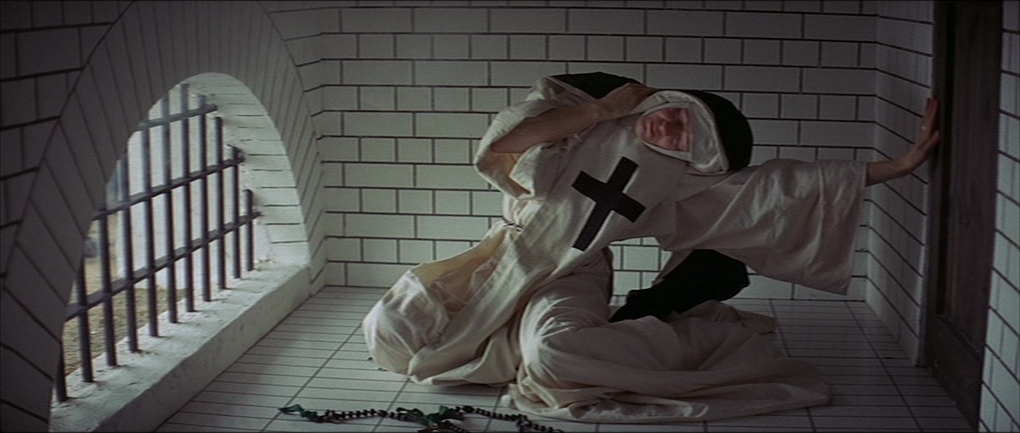

The dam was bound to break eventually, but never do we expect it to happen so violently, shattering the illusions of mundanity which conceal Jeanne’s mounting aggravation. Is this her escape from a limbo of domestic servitude? Is she trying to conquer an inconsistent world which has undermined her need for absolute control, or does the object of her forceful suppression lie within, secretly longing for pleasure? As Akerman’s final shot hangs on her at the dinner table, blood staining her blouse and hands, an ambiguous, peaceful smile makes its way across her face. Perhaps not even she has the words to express the gratification she has discovered, but with the boulder wilfully released from the top of the mountain, it is clear that this lonely, fastidious homemaker will never have to trek that torturous Sisyphean journey again.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.