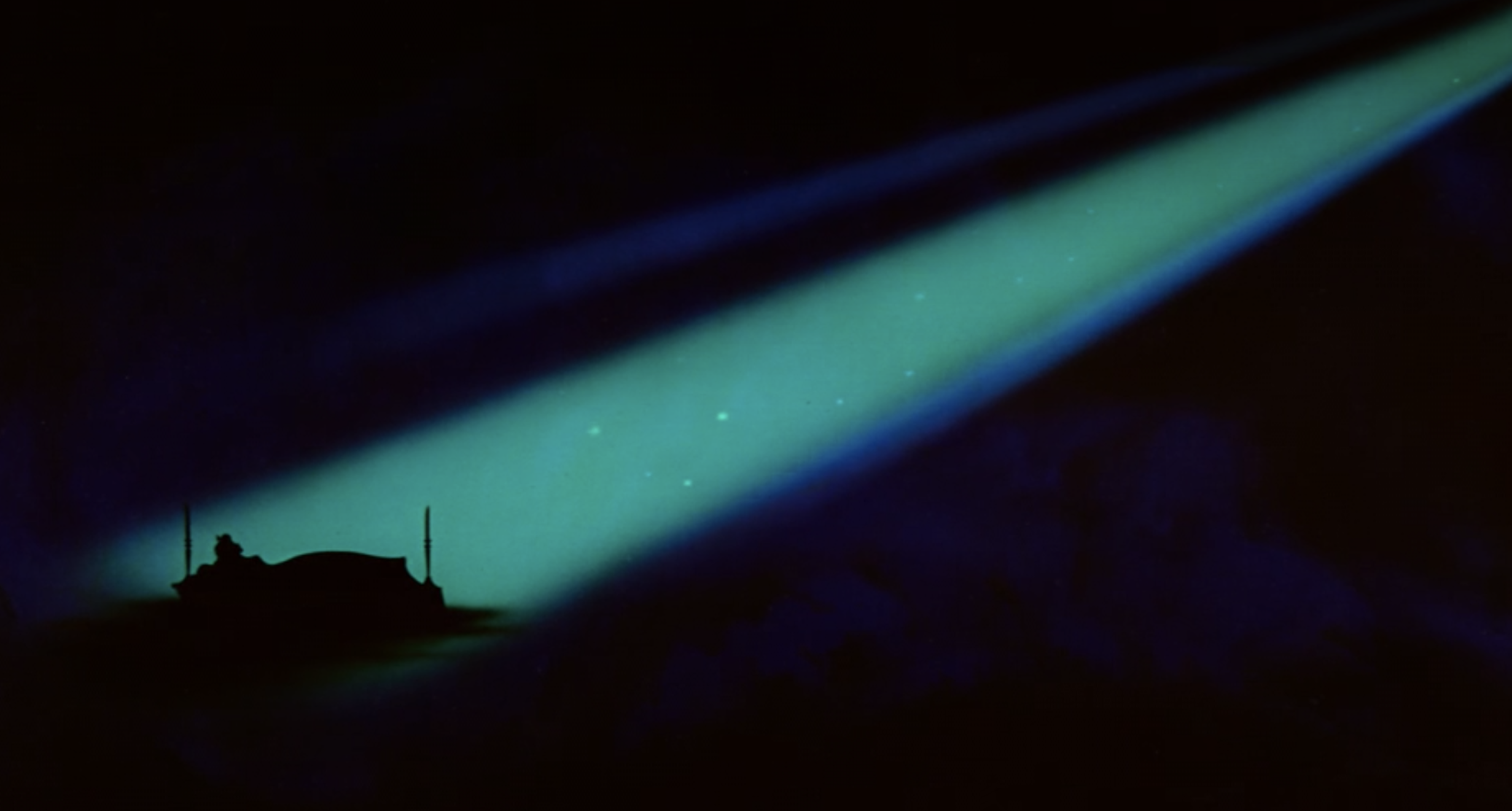

Shane (1953)

The looming Wyoming mountains form a majestic backdrop to George Stevens’ story of Western ranchers, gunmen, and sensitive melodrama in Shane, its vast landscapes containing a masterfully staged exploration of a modern America’s dwindling need for classical action heroes in favour of a new, civilised society of stability and prosperity.