John Ford | 1hr 58min

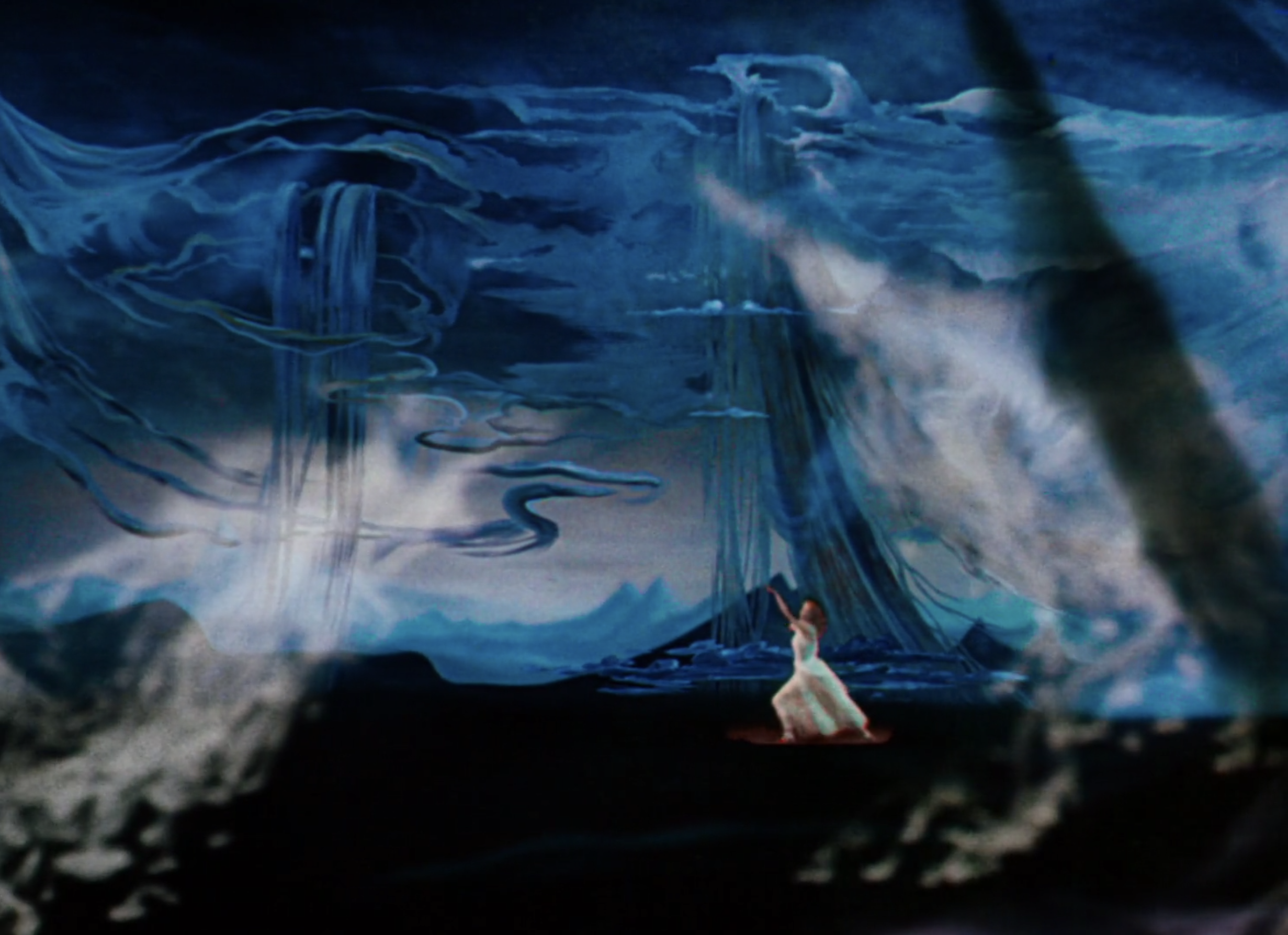

In transplanting his usual explorations of tradition and community from America’s old West into a rural Welsh village, John Ford finds a nostalgic beauty in the Victorian-era working class ideals of ‘How Green Was My Valley’. The saccharine adoration of the “olden days” comes with the territory of Ford’s films, though as usual it is also not so straightforward. As tight-knit as this fictional coal-mining town is, judgement and gossip run rife when someone steps outside its boundaries, and there is a hypocrisy to the small-mindedness of many villagers.

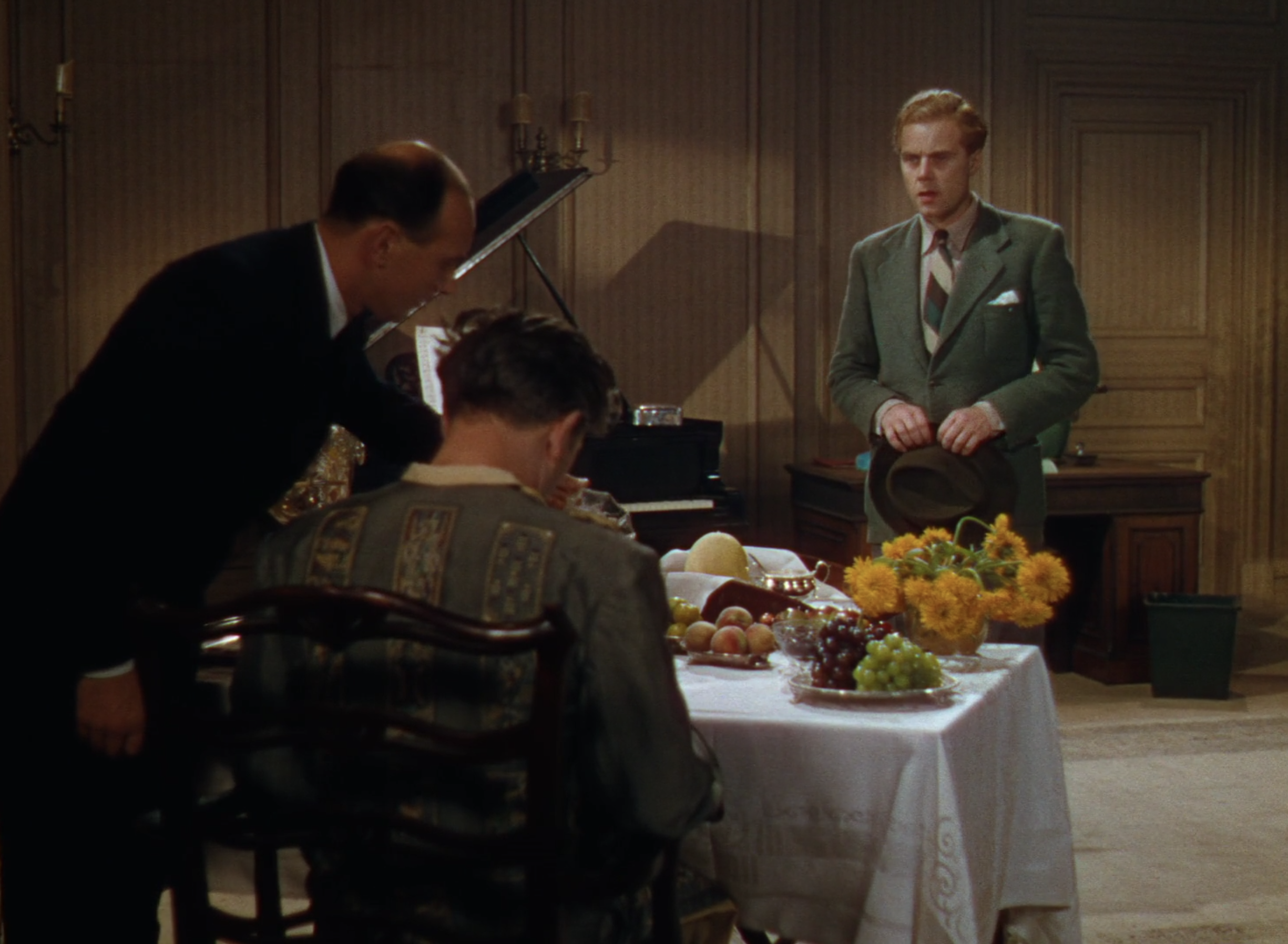

Nevertheless, the narration of an older, wiser version of our protagonist, Huw, reminisces on the idyllic peace of his childhood in this community, and the strength of the bonds between neighbours which got him through the roughest times. In Ford’s wide establishing shots of the town, people move and act in unison, singing, working, praying, drinking, and playing games like a single, cohesive mass. When they celebrate, the air is filled with hats being waved and tossed; when they hear the mine’s emergency whistle, they rush towards the site in common concern for their neighbours; and when one person is sick, the entire village walks down the main road in quiet solemnity to wish them well.

The townscape itself is an impressive set, with smoking columns, wooden structures, and triangular roofs rising up in uniform patterns from the modest, primitive village below. Gnarled trees with twisted branches line the edges of Ford’s frames, simultaneously confining the environments within which these characters interact with each other, and unifying the townsfolk in these quaint, natural spaces.

It is once the tranquillity and closeness of this blue-collar community is set up that Ford starts to reveal the forces chipping away its prosperity bit-by-bit. The first major threat is the wage cuts of the coal miners, with the ensuing strike only settling after many of them are made redundant. The industrial revolution is well underway by this point, and managers all over the United Kingdom are realising the expendability of loyal employees who demand more money than less experienced labourers.

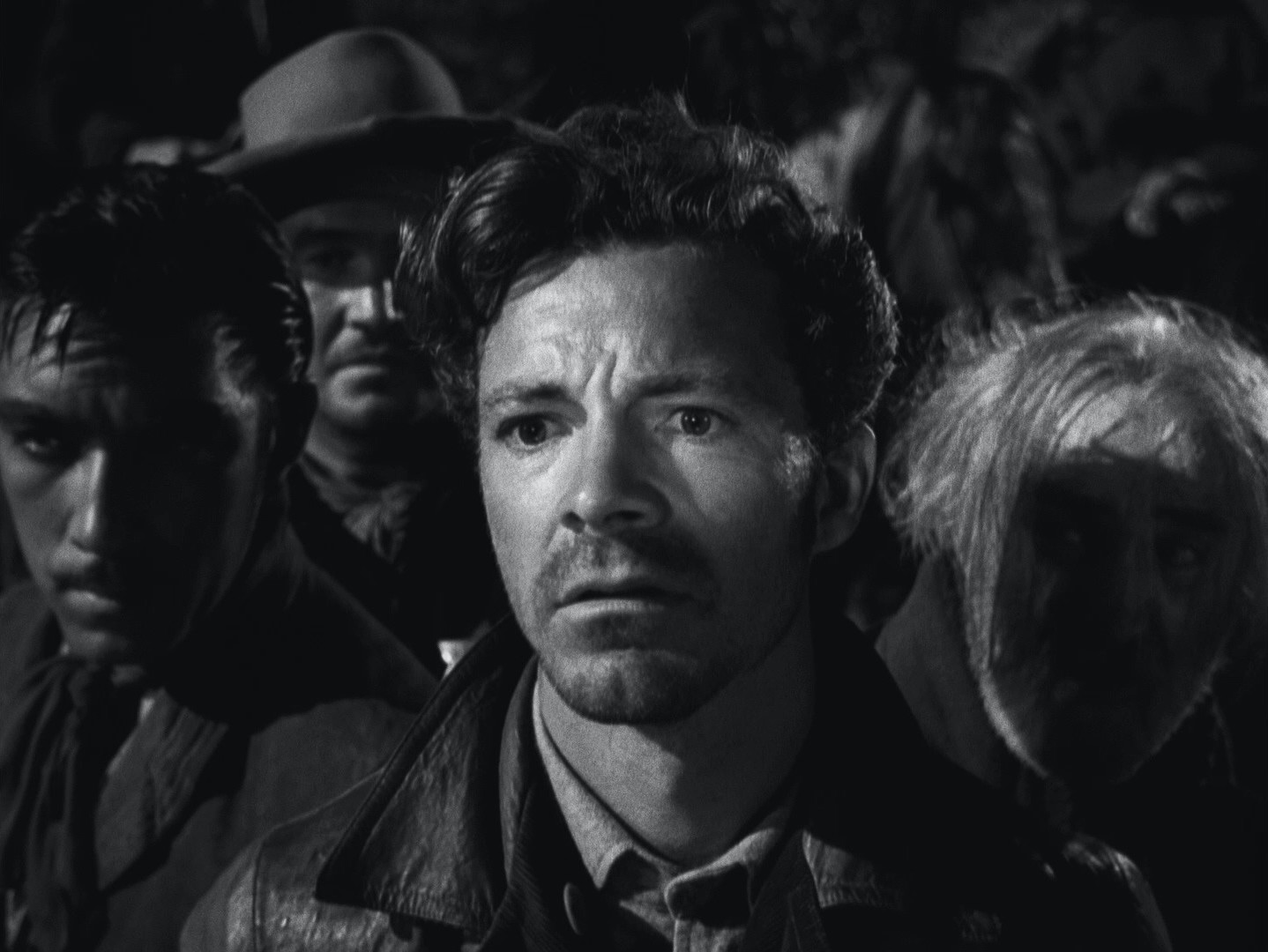

Paralleling the significant cultural shifts of 19th century South Wales are changes taking place within Huw’s own family. Realising the poor outlook of the industry, Huw’s father, Gwilym, pushes him away from the manual work which formed the bedrock of the Morgan family’s modest success, and down the path of formal education. Even in this polished, refined environment, Huw continues to absorb the rough, confrontational values of his village, engaging in fights with peers who ridicule him.

Meanwhile, Huw’s sister marries a wealthy man and moves away, one of his brothers dies in a mining accident, two others lose their jobs, and the friendly local preacher who forms the spiritual backbone of the village is driven away by the vicious gossip of his own parishioners. In a climactic final church service, he confronts those responsible for the private attacks on his reputation, addressing their selfish imitations of faith which actively erode the community’s open-hearted ideals.

“Why do you dress your hypocrisy in black and parade before your God on Sunday? From love? No. For you’ve shown your hearts are too withered to receive the love of your divine Father.”

While so many forces eat away at Huw’s innocence, he continues to persevere in his faith right up until the final, most devastating personal blow. When Gwilym doesn’t return from a cave in at the mine, Huw goes down below to investigate, journeying through the dark depths of the mine in much the same way as his father. Upon completing his mission, he rides the elevator back to the surface with his father’s body, mirroring his rise up into the role of family patriarch, and thereby effectively marking his complete loss of innocence.

We learn through Huw’s narration that he has spent the vast majority of his life trying to recapture the kinship that he once shared with his town, and it is only now, decades later, that he is finally leaving. “How green was my valley,” he laments, mourning the loss of an era that saw neighbours share each other’s losses and wins as a community. John Ford’s adoration of bygone eras may be considered twee or sentimental, but it doesn’t make his portrait of an idyllic childhood in Victorian-era rural Wales any less charming.

‘How Green Was My Valley’ is available to rent or buy on iTunes, YouTube, Google Play, and Amazon Prime Video.