Sergei Eisenstein | 2 Parts (1hr 40min, 1hr 26min)

So rapturous was the reception that Ivan the Terrible, Part I received from Joseph Stalin, it is hard to blame Sergei Eisenstein for recklessly pushing the boundaries of state censorship in its sequel. Both films are mirrors of each other – the first revealing an idealistic ambition in the young Ivan IV which Part II withers into paranoid cruelty, and together painting a vivid portrait of Eisenstein’s own shifting relationship with the Soviet Union. This was no longer the filmmaker who sought to reflect revolutionary principles in his experimental montage theory, but rather a disillusioned artist simultaneously defying and reluctantly cooperating with Stalin’s regime. It is a little ironic that the Communist dictator should see so much of him himself in the first Tsar of Russia, yet Eisenstein nevertheless took the metaphor as a creative challenge, risking his life and liberty to compose a vision of oppressive tyranny that stands true across centuries.

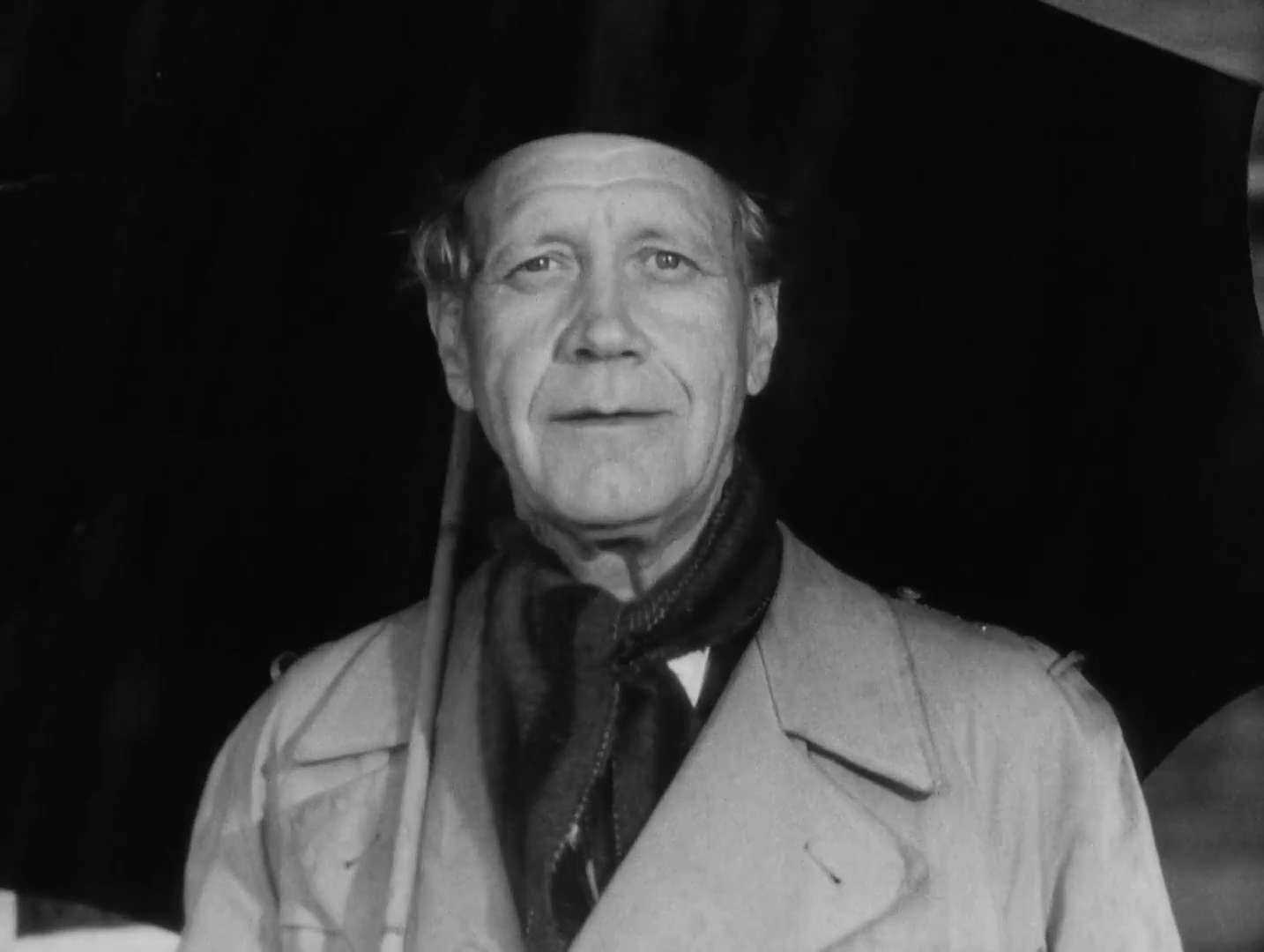

The casting of Nikolay Cherkasov as the imposing central figure here is particularly fascinating given his previous role in Alexander Nevsky, where he portrayed the titular 13th-century Prince of Novgorod. As a young, newly-coronated Ivan proudly declares Moscow a “Third Rome,” his eyes glisten with tears and hope, sentimentalising a vision of Russia’s future which doesn’t sound so different from Nevsky’s own utopian promise after vanquishing the Teutonic Knights.

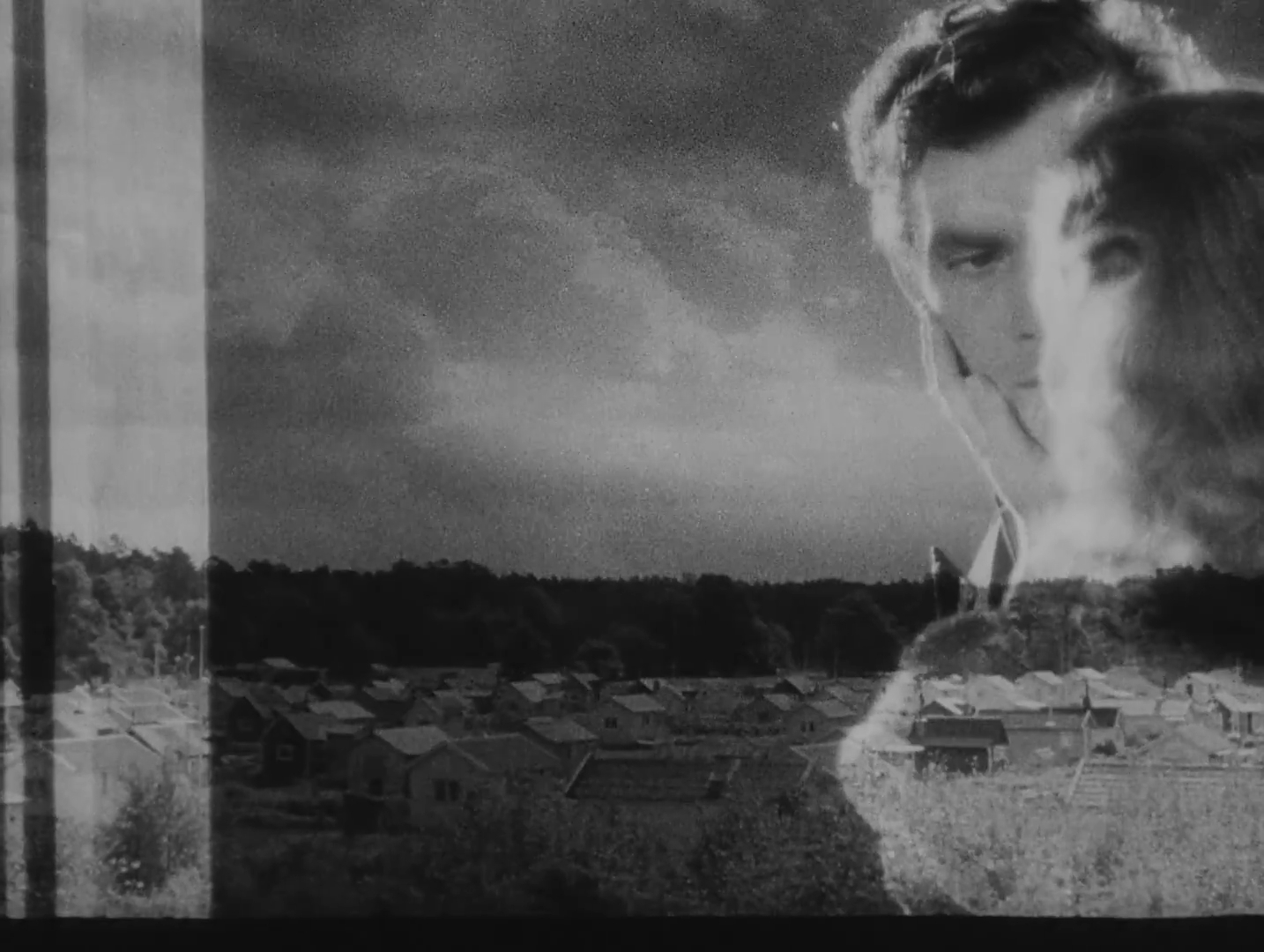

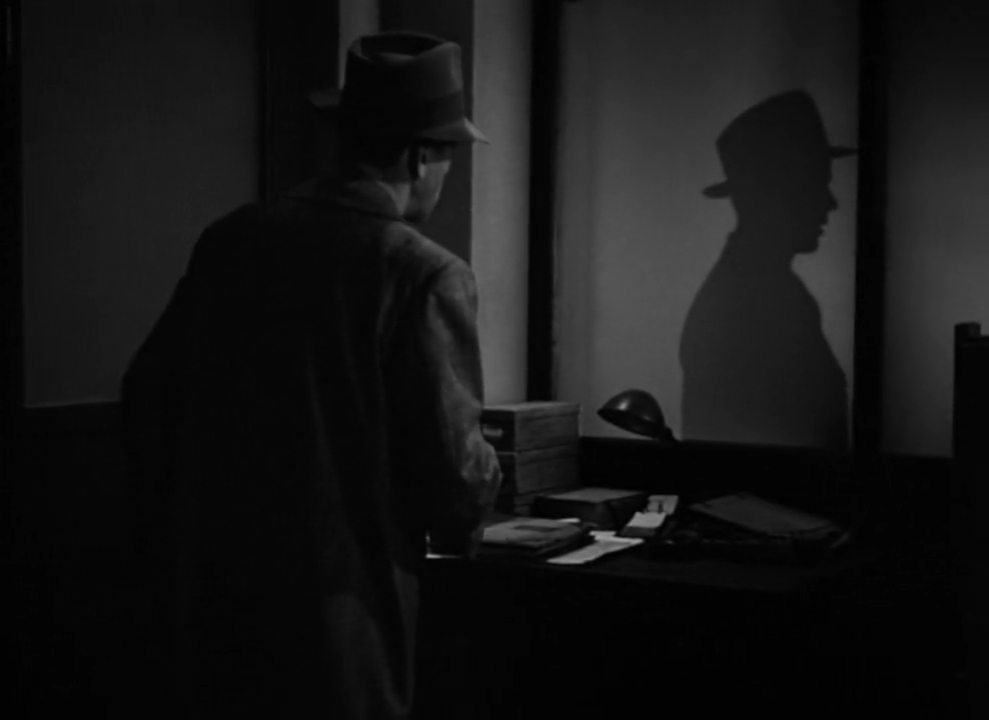

This is the ruler that Stalin admires, yet who is never viewed in such a pure light again after this moment, soon developing a distinctively hunched posture and angular facial features that become living extensions of Eisenstein’s majestic production design. Ivan’s bushy eyebrows, pointed beard, and crooked nose are virtually made for close-ups, and when his distinctive profile is cast in giant shadows upon the walls, he becomes a dark, physical embodiment of 16th century Russia’s formidable spirit.

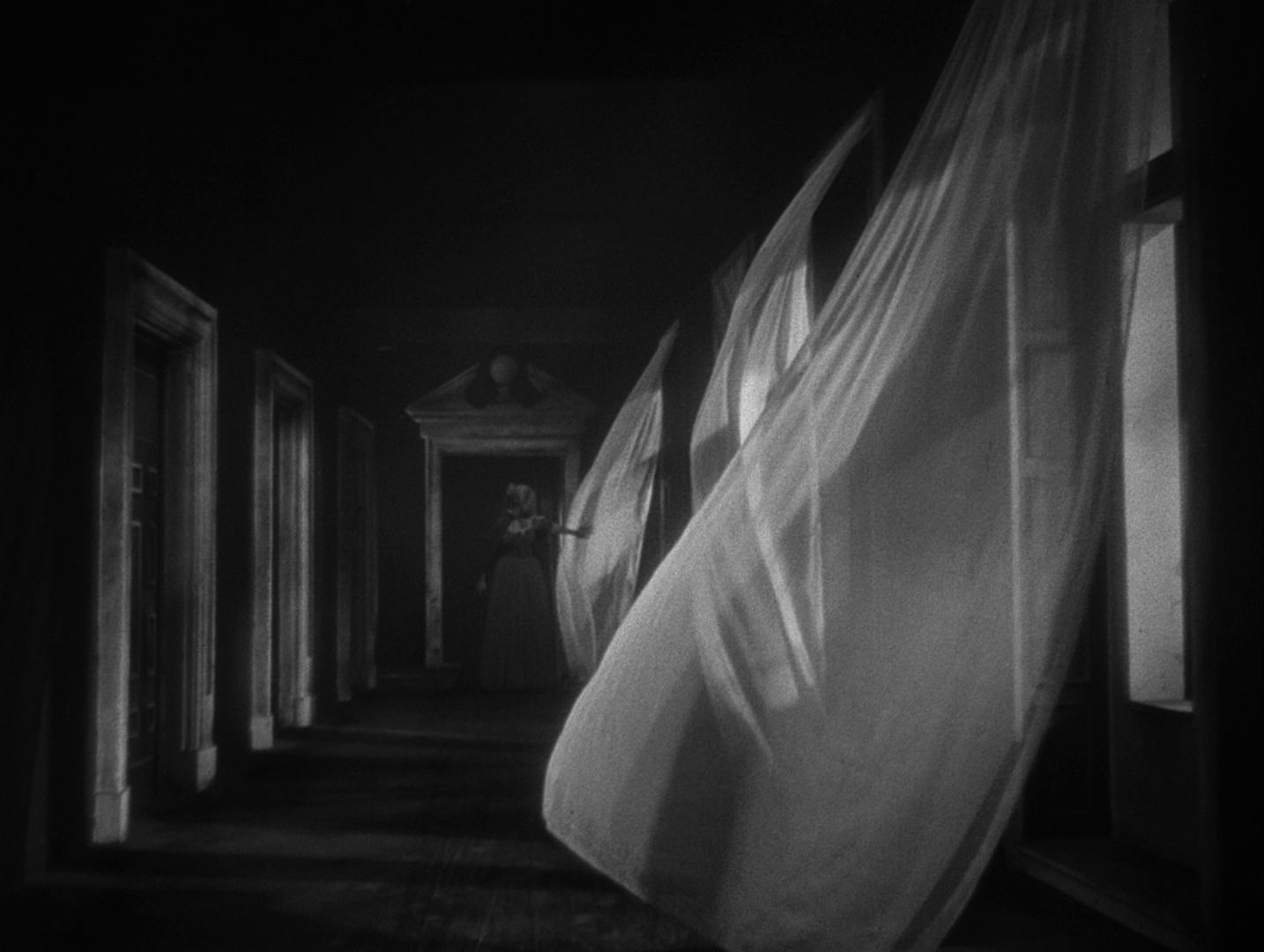

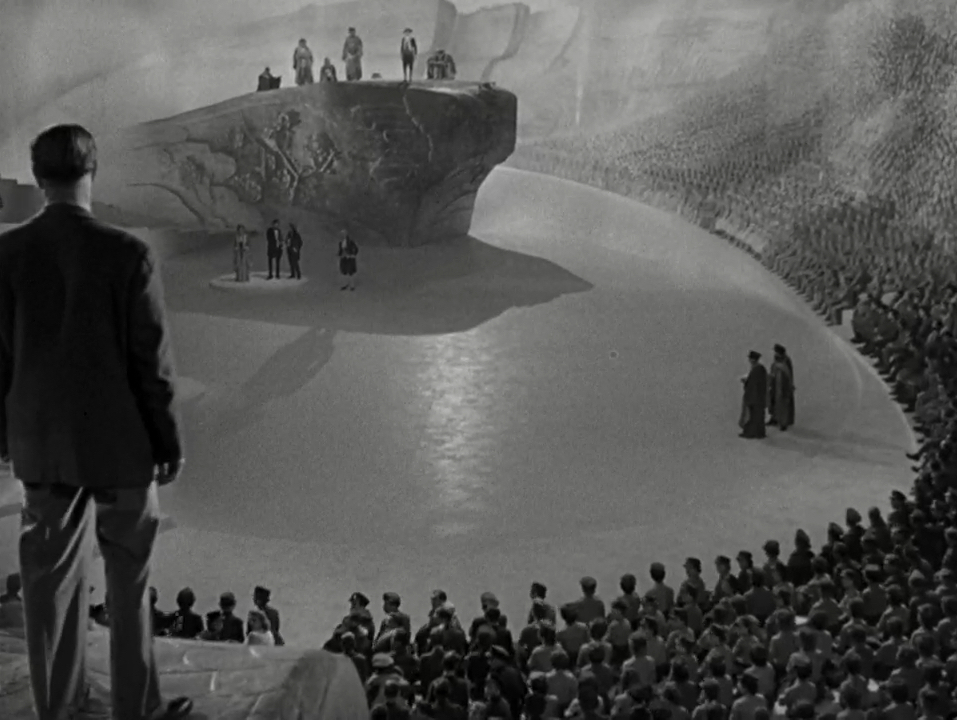

Only the Kremlin’s lavish interiors can match his awe-inspiring majesty with religious iconography painted across arches and columns, reliefs carved from its stonework, and collectively resting the Tsar’s legacy upon centuries of culture and history. Eisenstein’s rich depth of field especially flourishes here, sinking the masses to the bottom of frames that revel in the overhead architecture, and symmetrically positioning Ivan at their centre. These vast, intricate halls of power may very well mark Eisenstein’s greatest achievement in mise-en-scene, borrowing heavily from F.W. Murnau’s expressionistic imagery to cloak characters in chiaroscuro lighting, and underscoring their constant psychological tension between good and evil.

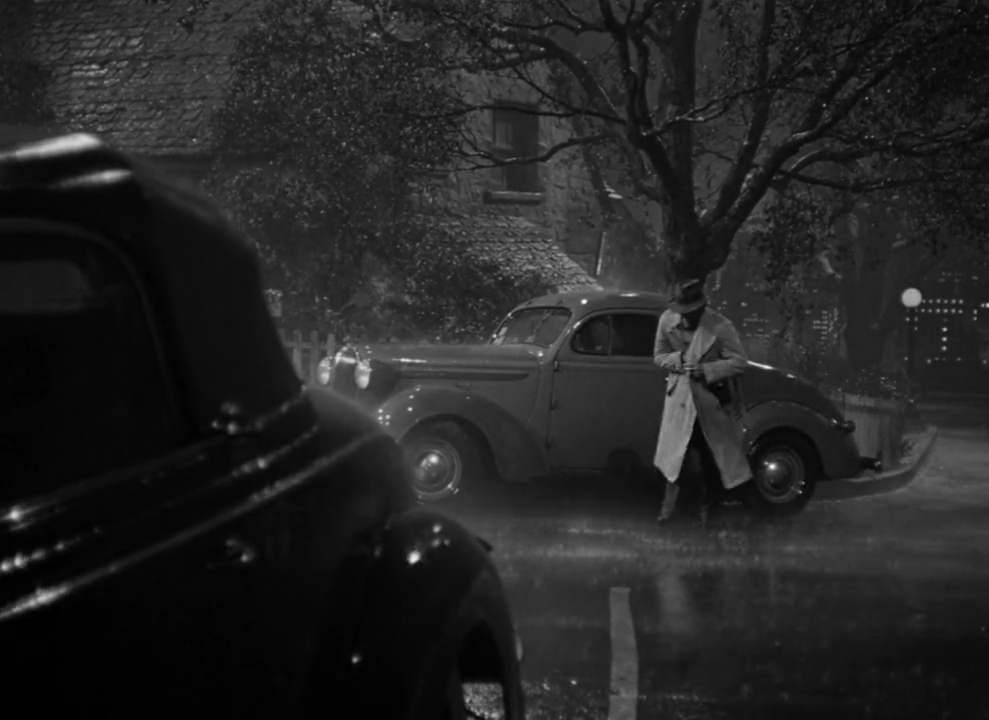

It is evident here that Eisenstein is far more than just an editor, though he nevertheless showcases those talents as well in the explosive siege of Kazan, where Ivan and his sprawling armies claim a stunning victory against the Khanate. As soldiers wait patiently upon hillsides with their cannons and banners, sappers furiously dig tunnels beneath the walled city to plant gunpowder, and Eisenstein clearly relishes the practical effects granted by his enormous budget when the time comes to blast brick, mortar, and smoke into the air. Rather than wielding his editing for intellectual purposes, here he dedicates it purely to the vast scale of his action, building Ivan’s grand authority upon the conquest of those who dare oppose his rule.

For the most part though, the greatest political threats to the Tsar are located within his own ranks, as conspirators plot to install his simple-minded cousin Vladimir as Russia’s true sovereign. The political intrigue carries a Shakespearean gravity to it, modelling Ivan after the likes of Macbeth or Richard III, and watching his games of manipulation unfold with treacherous delight. When he falls deathly ill and names his son Dmitri as heir to the throne, his aunt Yefrosinya is quick to whisper into the embittered Prince Kurbsky’s ear, perniciously encouraging him to announce her son Vladimir as the rightful successor instead. Kurbsky is smart to sniff out Ivan’s test of his loyalty here, as almost immediately after carrying out his wishes, the recovered Tsar emerges from his chambers and rewards his allegiance.

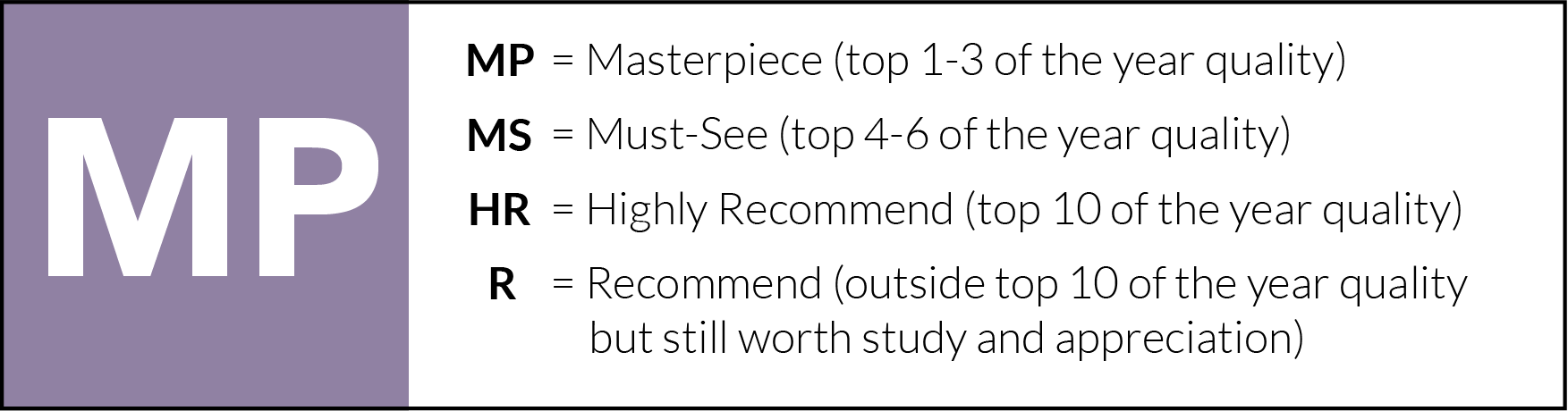

Yefrosinya, on the other hand, is not so restrained. Though she prefers to pull strings from the shadows, she isn’t above getting her hands dirty, going so far as to weaken Ivan’s rule by poisoning his wife Anastasia. Later when he makes an enemy of Metropolitan Philip by overruling his religious authority, Yefrosinya again leaps on the opportunity to stir dissent among his followers, only this time rallying them behind an assassination plot that targets Ivan himself.

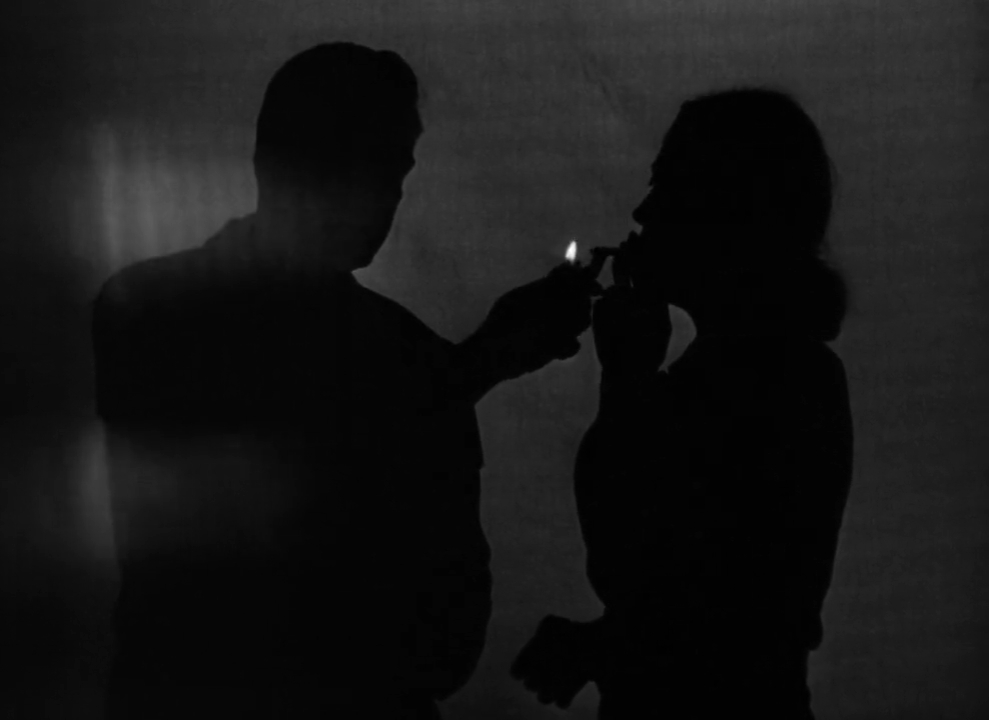

The murder is to take place after a banquet and theatrical performance, where Ivan the Terrible suddenly departs from the black-and-white photography which has dominated Eisenstein’s career thus far and catches aflame with hellish red hues. This vibrant burst of colour is a shock to the senses, accompanying Ivan’s final and perhaps most despicable act. Having plied Vladimir with alcohol and extracted the conspiracy from his lips, he mockingly dresses him in his own royal regalia, and lets him lead his entourage to the cathedral in prayer. Black, hooded figures trail behind Vladimir like spectres of death, and from the shadows the killer pounces, sinking his dagger into the flesh of the disguised prince.

Yefrosinya’s celebration is critically premature. “The Tsar is dead!” she joyfully proclaims, before recognising the tragic turn of events which has befallen her son. Ivan cares so little for these traitors, he does not even bother to have them executed. After all, they are the ones who killed his worst enemy, and who have effectively destroyed themselves in the process.

With Ivan’s greatest threats in Moscow eradicated, the time has thus come for him to turn his attention to those on the outside – yet it is at this tantalising climax that we are left wondering what a third part to Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible trilogy might have looked like. Stalin’s fury at Part II’s tyrannical depiction of the Tsar not only kept the sequel from being released until 1958, but immediately ended production on Part III, destroying all but a single fragment of its footage. Even without completion though, the legacy of this truncated series is nevertheless secured in Eisenstein’s daring ambition. Through bold, inflammatory strokes, waves of Russian despotism are painted out in striking detail, reaching across centuries to impose familiar cruelties on this nation’s long-afflicted people.

Ivan the Terrible is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.