Passing (2021)

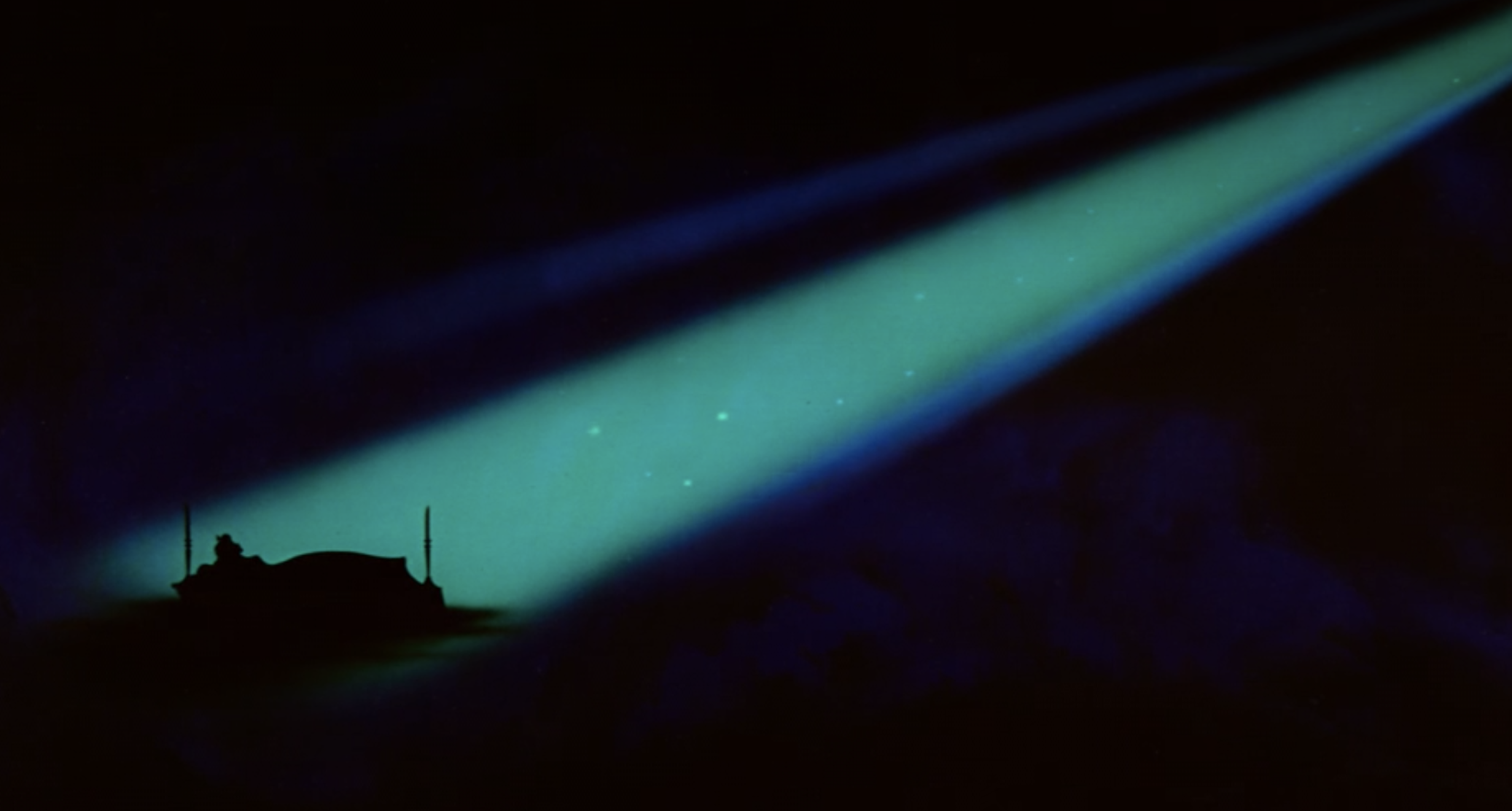

Rebecca Hall’s shallow focus and hazy black-and-white cinematography in Passing takes a dreamy hold over this interrogation of racial assimilation in 1920s New York, bringing together two old African-American childhood friends whose strikingly divergent lives lead to a reunion over thorny questions of identity and prejudice.