David Lynch | 2hr

Evil is very real in the films of David Lynch, and so it stands to reason that there also exists a naïve, pure goodness in opposition to it. His binary worlds of light and darkness do not suggest a lack of complexity though, but rather an intricate symbiosis that exists between the two, and which he draws right through the mind of Jeffrey in Blue Velvet. The young college student’s idyllic hometown of Lumberton warmly welcomes him back when his father suffers a heart attack, and during his stay with his mother and aunt, the community’s happy mundanity eats away at his patience for such sterile living.

Perhaps it is the taste of mortal danger that comes with his father’s illness that motivates his new macabre interests. It certainly at least opens a gap in his life for a new patriarchal figure to step in, tantalising Jeffrey with the prospect of something darker and more exciting lurking beneath Lumberton’s artificial small-town veneer. Bit by bit, the layers of a mystery behind a severed human ear he finds in an open field are peeled back, revealing conspiracies and corruption far more psychologically disturbing than anything he might have ever conceived. His struggle to appease a craving for both knowledge and security is thus the battle that Blue Velvet wages on temperamental, psychological terrain, striving to find resolution between the conflicting desires that shape minds and cultures.

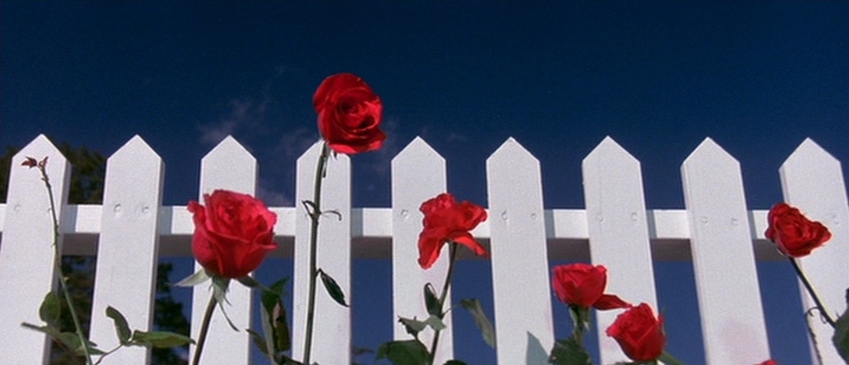

Blue Velvet’s stark duality is one that Lynch paints right into his expressively bold mise-en-scene, in part evoking the patriotic red and blue of America’s national colours, though primarily using the heavy contrast between these hues to set apart the danger and tranquillity of two co-existing worlds. It makes sense then that within the apartment of psychopathic drug dealer, Frank Booth, the carpet, couches, and wallpaper are dyed a shade of deep maroon, and that his captive, Dorothy Vallens, dresses similarly. When she first changes into that titular blue velvet dress though upon meeting Jeffrey, there is a subconscious attempt in her sartorial choice at soothing those harsher tones with a melancholier countenance. Whether in the curtains and lighting of Dorothy’s cabaret performance, or the eye shadow and lipstick decorating her face, Lynch’s primary colours constantly clash against each other, composing a chaotic world of stylistic dissonance that breaks down our desire for visual harmony.

This is the tragedy that has already broken Dorothy into pieces by the time we meet her, as we discover Frank has kidnapped her husband, taken her son hostage, and is keeping her as a sex slave. The volatility and fragility of Isabella Rossellini’s acting here is only rivalled by Dennis Hopper’s wildly loose performance, and while we are taken aback to find a sadomasochistic side to the otherwise vulnerable Dorothy, there is a sensitivity which we are even more astonished to see in Frank’s face as he tearily watches her sing at the nightclub. Both contain complexities far beyond anything Jeffrey has experienced before, and so while the danger remains perfectly apparent, he can’t help but gaze on with insatiable curiosity.

The Hitchcockian undertones of Jeffrey’s voyeuristic peering through the slats in Frank’s living room closet are not easily missed, with Lynch setting up an image of forbidden desire slowly emerging from its dormancy, intrusively spying on the violent sexual activity taking place on the other side of those doors. Terror and exhilaration are inseparable at this point for Jeffrey, as within the unrestrained psychosexual dynamic of two people calling each other “Mommy” and “Daddy” there is a Freudian transference taking place. Not just for Dorothy and Frank, but Jeffrey as well, whose passive mother and ailing father have left a vacant space for him to consider substitutes belonging to the darker, unexplored side of his mind.

The formal work Lynch does in mirroring relationships all around Jeffrey extends to his newfound romance with Sandy, the daughter of the local police detective handling the case of the severed ear. Between her and Dorothy, Jeffrey’s sexual self-discovery travels along parallel paths between two women in current relationships, and consequently pushing him towards a transgression of social norms in both instances. But where Dorothy dresses in the bold hues of red and blue set out in Lynch’s primary palette, Sandy is defined by her soft pastels. While Dorothy is a European woman with a shock of curly black hair leaping off her head, Sandy is a blonde, all-American girl-next-door type. Where Dorothy pulls Jeffrey deeper into his primal instincts, begging him to hit her like Frank does, Sandy questions his newfound obsession with Lumberton’s mysterious crimes. His response does not so much suggest an explicit interest in the details of the underworld as it does a novel intrigue in its mere existence, compulsively driving him towards the parts of himself that society dictates must be actively inhibited and kept out of view.

“I’m seeing something that was always hidden.”

The unsettling visual motifs that Lynch returns to in representing this war of innocence and corruption epitomise the style of suburban surrealism that he specialises in, bordering on absurd in the collision of these incongruous threads. The image of Lumberton set up in the introduction with its green lawns and white picket fences is superficially bright, making Jeffrey’s father’s heart attack the first sign of anything less than total, picturesque bliss. In the twisted hose pipe and the phallic stream shooting from his groin area, Lynch is already weaving in symbols suggestive of the father’s blocked artery and sexual impotence, relegating him to the background of Jeffrey’s story. As the camera narrows in on the freshly cut lawn, the imagery and sound design only grow darker with the emergence of bugs, fading out the smooth tunes of Bobby Vinton’s ‘Blue Velvet’ while their skittering and mulching take over, accompanying the movement of their grotesque bodies across the lens in total domination of the space.

Later when Jeffrey first goes to investigate Dorothy and Frank’s apartment, he takes on the disguise of a pest exterminator, setting him up in opposition to the ugly forces that crawl beneath the surface, though when he begins to fall into their world of sexual deviancy and depravity, it is stripped away to reveal his naked, authentic self. The moment he finally submits to her desire to be hit during sex, there is something unleashed within himself as well, represented by Lynch’s dreamscape as a burst of cutaways to fiery explosions. Unlike Frank, he is not proud of this side of himself and hides it away, though the subconscious can only last so long in the shadows before it rises to the surface. It is almost comical how insignificant the subplot regarding Sandy’s real boyfriend is next to everything else, as his angry confrontation with Jeffrey quickly dissipates in the face of the much larger issue of Dorothy’s sudden appearance, naked, wounded, and begging for his love. For the first time, the two main women in his life meet, and that which represents ordered civility can barely handle the uncomfortable manifestation of his shameful, repressed instincts.

If Frank is the darkest possible version of Jeffrey, and the closet where they met signifies the threshold where repressed longing is released, then it is in a return to that setting where his shadow self must be killed. Lynch’s indulgence in Jungian archetypes rings deeply through these characters, strengthening their relationships within pseudo-families and sexual dynamics that cut to the root of their desires. The restoration of order in the lives of Jeffrey, Sandy, and Dorothy comes not as a blind withdrawal back into suburban frivolity, but rather a healthy recognition of one’s most primal impulses and their purposes. After all, it was only following his first sexual encounter with Dorothy that he was able to muster up the confidence to pursue Sandy more seriously, helping him understand the dangerous power he is capable of so he may draw on it in a controlled, judicious manner.

The appearance of a robin outside Jeffrey’s aunt’s window seems to come straight out of Sandy’s dream from earlier as an emblem of love, and with its devouring of an insect, Lynch effectively ties off the two running motifs in a conquest of evil. “I could never eat a bug,” Jeffrey’s aunt proclaims with disgust, but Jeffrey is wise enough to know that keeping a little bit of iniquity inside oneself is necessary. In place of the severed appendage that led him into trouble and Lynch’s camera wandering into its dark orifice, we now linger on Jeffrey’s own ear, whole and unharmed, and travel in the reverse direction, pulling out into a wide that restores the world to its logical order. Blue Velvet could be read as a coming-of-age film through its discovery of worlds and minds that are not what they seem, though the depths it plunges into humanity’s psychosexual awakening, disconcerting iconography, and bold palettes places it in a transcendent, artistic class of its own.

Blue Velvet is currently available to rent or buy on iTunes, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

Another great review for one of my 25 favorite films ever made. You’ve been killing it lately!

Thanks Jeff A! I found myself with a bit more free time than usual recently so was able to really work through some classic masterpieces and sit with them for a bit. I think I prefer doing it this way even if I’m not getting new reviews out every day.

What a great review, Declan. I don’t know your opinion (or if you even have an opinion on your own work), but this might be your best review. Anyway, I think you’re spot-on about this being a coming-of-age story. I just rewatched the film and that’s exactly what I was thinking. Very good work!

Thanks Pedro, very much appreciate the kind words! I’m definitely prouder of some of my reviews over others, but of course it is also easier to pick apart great films like this with plenty of meat on the bones. With lesser films it sometimes feels like a bit of a dry well to draw from.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1980s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Male Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green