Wim Wenders | 2hr 5min

It isn’t that Japanese toilet cleaner Hiriyama is discontent with his janitorial duties in Perfect Days, nor that his lowly status at the bottom of Tokyo’s working class is eroding his spirit. If anything, his methodical repetition of the same procedures from day-to-day is a soothing meditation, finding fulfilment in the conscientious act itself rather than the end goal. It is fortunate too that this motivation is so self-sustaining, given that these toilets are almost immediately soiled by the public the moment they are cleaned. There is little external gratification to be found in this line of work, and thus Hiriyama’s Zen-like mindset breeds an appreciation for its small, unassuming details, from his car playlist of classic rock to the trees he photographs in his lunch break.

Still, there is something missing here, gradually revealing itself as time stretches on without him speaking a single word. Hiriyama may be the loneliest man in Tokyo, only ever interacting with his capricious younger colleague who talks enough for them both, and the regulars at the public bath and restaurant that he visits at the end of each workday. He is a man comfortably bound by tradition, yet mildly perturbed by those unpredictable disruptions which throw off his perfectly balanced schedule. At least by minimising the influence of external factors, he can maintain that peaceful equilibrium in his life, even if it means never truly understanding the happiness that comes through sharing it with others.

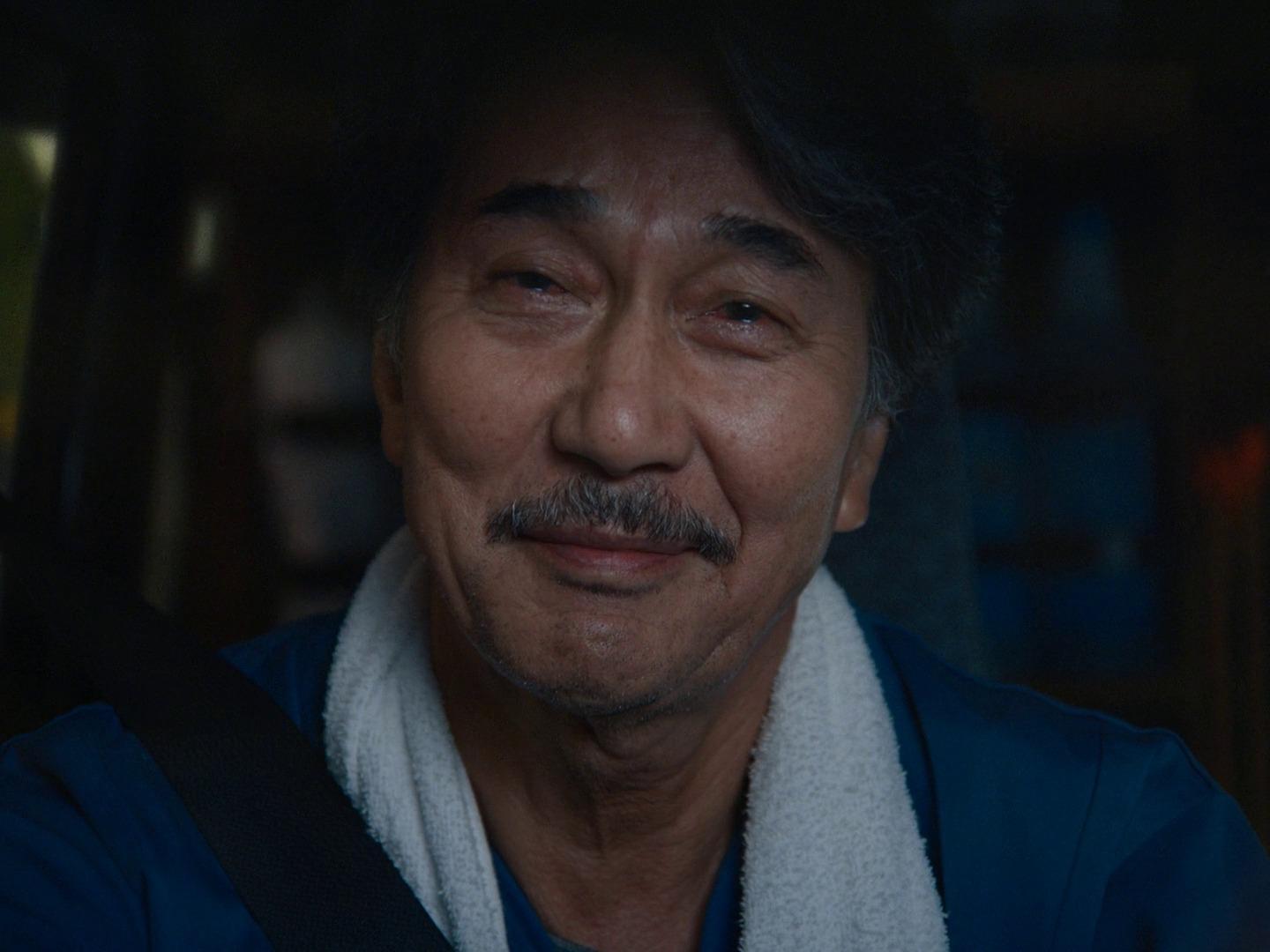

It has been some time since Wim Wenders has directed a film that has emerged from Cannes Film Festival with such high acclaim, and while Perfect Days does not quite reach the cinematic heights of his work in the 80s, it is compellingly consistent with his pensive elevations of mundanity. Where Wings of Desire flitted between stream-of-consciousness voiceovers from the minds of ordinary people though, Perfect Days denies us any verbal entry into Hiriyama’s inner world, leaving us only to gage his character through Kōji Yakusho’s largely silent performance and Wenders’ rigorous narrative structure.

It is especially in the latter that this minimalist meditation attains impressive formal rigour, thoroughly setting up Hiriyama’s routine on the first day that we spend with him, and then repeating it with minor variations. By the time the second day arrives, we can virtually predict each beat with reliable accuracy – the way he folds up his floor mattress, his spraying of his pot plants each morning, and even his daily purchase of coffee from the same vending machine outside his rundown flat. The restrooms that he visits daily become his domains, each standing out in ordinary parks as architectural marvels, such as one brutalist structure made up of harsh angles and another with colourfully transparent walls that turn opaque when locked. Though Hiriyama can see straight through when it is unoccupied, he nevertheless knocks on its doors before entering, if for no other reason than to carry out his habitual duty.

Over time, the patterns which emerge in these recurring actions, location, and shots imbue Perfect Days with a formal precision evoking Yasujirō Ozu’s sensitive domestic dramas. Unfortunately, Ozu’s dedication to carefully arranging the frame does not quite carry through in the same way here – an unusual oversight for Wenders whose previous films have featured the sort of austere photography that would have strengthened Perfect Days’ exacting focus. Perhaps the greatest flashes of style here arrive in the hazy, greyscale dreams which structurally divide one day from the next, weaving in abstract visions of Hiriyama’s waking life through a series of long dissolves. Trees, shadows, wheels, and pedestrians call upon recent memories with gentle repose, while very occasionally we catch glimpses of familiar faces that have taken root deep in his subconscious.

Quite prominent among these illusory nighttime visitors is Hiryama’s niece Niko, who unexpectedly turns up at his apartment building one evening to stay with him. Whatever trouble has been unfolding at home is none of his business, especially given the clearly estranged relationship he has with his upper-middle class sister, Keiko. Hiriyama desperately tries to maintain a semblance of routine through her passive disruptions, yet her insistence on joining him at work forces him to share his meditation with someone else for the first time, and very gradually we witness a wondrous evolution take place in this relationship. Not only does Hiriyama speak, but through this connection he even relishes his usual habits even more – photographing the trees on his old film camera while Niko does so own her phone for instance, and riding bikes on the weekend through the streets of Tokyo.

When the time comes for Keiko to take her back home, Hiriyama is quietly distraught. Perhaps not only due to the tender relationship that has been snatched from him, but Keiko’s visit has also instigated a confrontation with his own selfish habit of isolating himself from others. From this perspective, Hiriyama’s meditative lifestyle may be little more than an escape from the pressures of a complicated world, which when faced head-on send him falling back on unhealthy habits.

Still, journeying outside one’s comfort zone is an adventure that inevitably entails stumbles and bounding leaps, both equally disturbing the precarious routine that Hiriyama has carefully cultivated. With the decision to boldly initiate social contact comes a spiritual rejuvenation that work alone cannot fulfil, no matter how relaxing its gentle rhythms and cadences may be. That Wenders weaves these so smoothly into the rigorous narrative structure of Perfect Days is not only a testament to his own formal attentiveness, but also consolidates communality and introspection with prudent devotion, inviting audiences into a deep reverie of collective contemplation.

Perfect Days is currently playing in theatres.

Kōji Yakusho is also the lead actor in the acclaimed Kiyoshi Kurosawa film Cure (1997). Interesting.

LikeLike

He’s got an interesting resume for sure – also teamed up with Inarritu on Babel.

LikeLike

Yakusho is also the lead actor in the Imamura film The Eel in 1997. The same year as Cure.

LikeLike