Luca Guadagnino | 2hr 16min

Early in Queer, we delve into writer William Lee’s nightmare of his friends in prison, an abandoned baby, and a naked woman bisected along her torso. The symbolism opaquely hints at the guilt harboured by William Burroughs, the real-life novelist who based this troubled character off himself, though it is his response to this woman questioning his sexuality which articulates the film’s most layered metaphor.

“I’m not queer. I’m disembodied.”

The separation between Lee’s self-loathing thoughts and pleasure-seeking instincts drives a wedge into the core of his identity as a gay man, and is further reflected in Luca Guadagnino’s dissociative direction, often letting the writer’s mind escape his physical being. Early in his relationship with the much younger Eugene, Lee’s yearning is often rendered as a transparent, ghostly version of himself reaching out to caress his face or lean on his shoulder, though it also manifests even more darkly in his indulgent vices. Drugs and alcohol offer easy escapes from the shame of his sexuality, and even sex too ironically satiates that desire for euphoric sensation as it simultaneously feeds that underlying guilt.

The 1950s was not a particularly hospitable time for the gay community, yet there was also a certain level of privilege that came with living as a white man in Mexico City which Lee and his similarly ostracised friends use as a social counterbalance. This circle of outsiders is relatively insular, so when Eugene arrives at their local bar flirting with both men and women, Lee is instantly drawn to his mysterious allure. This is a man who hides his emotions so well that others question whether he really is gay, striking an intense contrast against our verbose protagonist’s overbearing tendency to persistently chase interactions. When Lee leans in, Eugene often hesitantly pulls away, making the few moments of organic connection between all the more valuable.

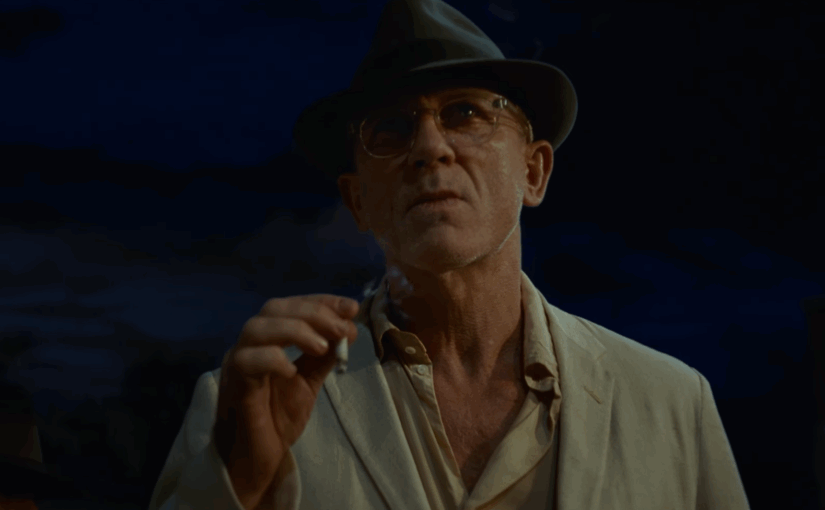

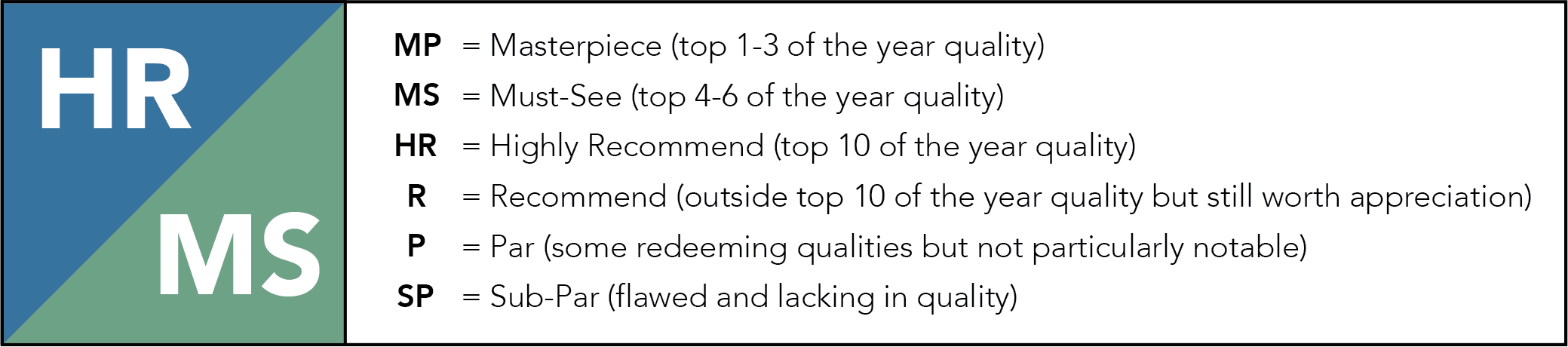

There was never any doubting Daniel Craig’s talents during his time as James Bond, though the performance he delivers here as the eloquently eccentric Lee is his most layered yet, leaning into the weariness of a middle-aged man whose existential insecurities are only amplified by his ageing. He inhabits a world that is one level removed from our reality, filling in the malaise with the bold, bright colours that often decorate Pedro Almodóvar’s melodramas. Within the lush purple and red lighting of a hotel bedroom and the yellow décor of his apartment, his inner life is given passionate outward expression, though Guadagnino’s stylistic achievement does not end there either. From a distance, the city is often whimsically rendered through miniatures, making cars look like toys and buildings like dollhouses. In an ending that thoughtfully borrows from the final act of 2001: A Space Odyssey, this visual motif pays off when Lee hallucinates another version of himself inside a diorama of the hotel where he is staying, further splitting his mind and his body between entirely different realms.

The height of Queer’s surrealism though arrives when Lee and Eugene venture into the deep jungles of South America, seeking a plant which is said to grant telepathic abilities. It is no wonder why Lee should be so obsessed with such a prospect – if the rumours are true, then perhaps this higher form of communication is a treatment for his emotional isolation, allowing a union of souls which regular conversation and sex cannot attain.

Although Guadagnino largely maintains the novella’s literary quality through his chapter breaks, he takes creative liberties in departing from its depiction of the drug trip here. Where the source material saw Lee disappointed by its underwhelming effects, the film submits to the psychedelia, having him and Eugene literally vomit out their hearts before exposing their truest feelings. “I’m not queer,” Eugene asserts, formally echoing Lee’s earlier words as his body fades from view during their hallucinogenic drug trip. “I’m just disembodied.” Indeed, these two men have never been more detached from their physical beings, and have never been more in synchrony as their bodies grotesquely merge into one. Limbs move beneath fused skin as they dance, and for one precious night, Lee truly escapes his shame and transcends his loneliness.

This drug is not some portal into some other place though, their dealer Dr. Cotter is sure to warn them. It is a mirror into one’s soul, offering a glimpse at whatever desires and fears lurk beneath their consciousness. Its euphoria is short-lived, particularly for Eugene who wakes up the next morning anxious and eager to leave. It is a terrifying thing losing a part of oneself to another person, and when faced with the truth of his relationship with Lee, he sees its toxicity for what it is.

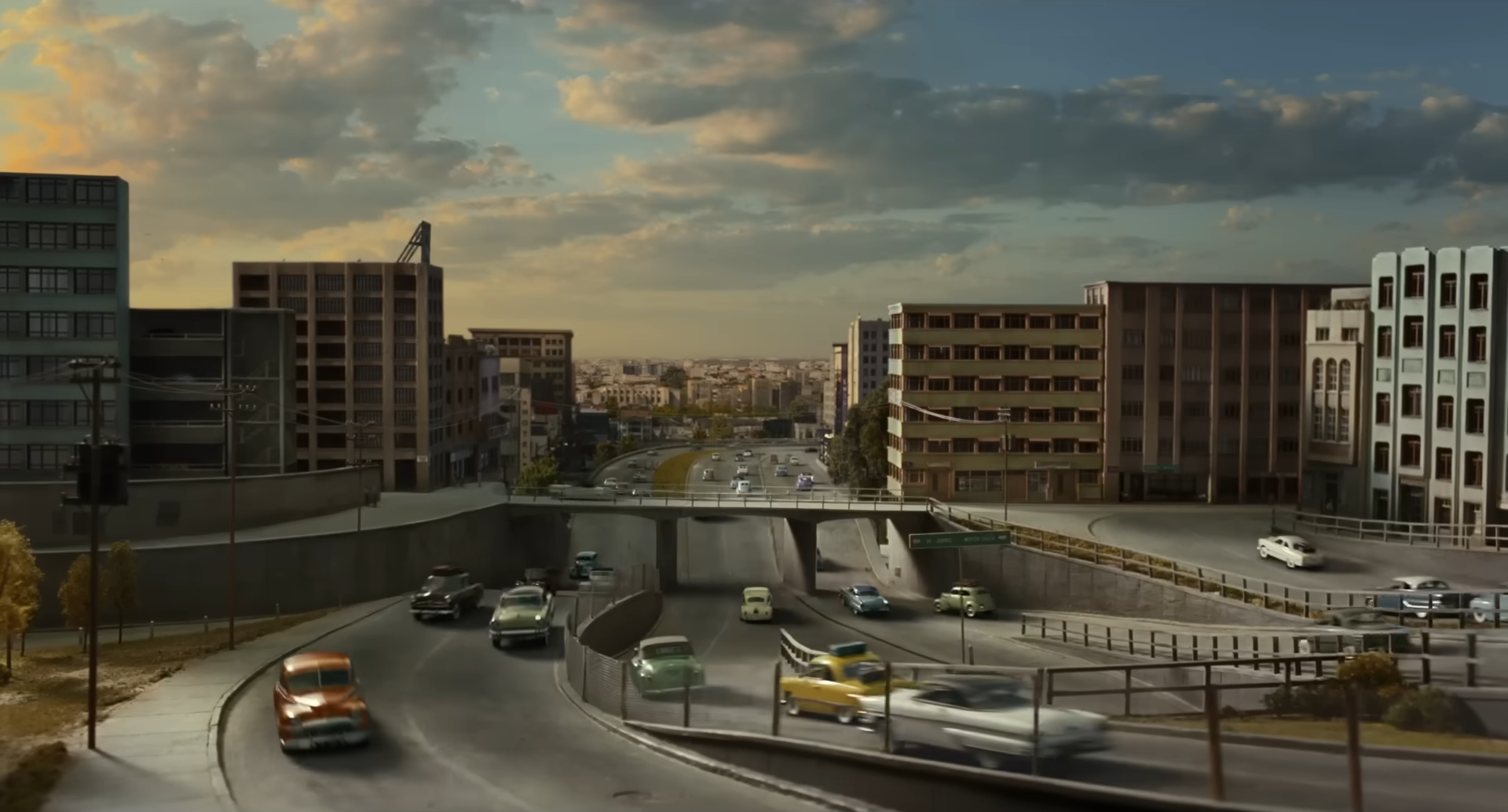

The recurring centipede is one of Guadagnino’s more cryptic symbols in Queer, and its unsettling appearance in Lee’s dream of Eugene many years after their breakup continues to hold him in an unresolved state of suspension. Just as it first appeared around the neck of a one-night stand, the centipede now marks Eugene as another fleeting lover, manifesting the real-life Burroughs’ self-confessed fear and cherished literary motif. Lee’s story is unfinished in Guadagnino’s eyes, leaving him a half-complete man torn between dualities – shame and indulgence, connection and independence, mind and body. As long as he strives to separate rather than reconcile these parts of his identity, he will continue to live in a world of dissociative nightmares, spiritually and psychologically divorced from himself. Through the colourful, eerie patterns that Guadagnino consequently uncovers in Lee’s character, Queer delivers an unflinching fever dream that denies easy answers to his internal contradictions, constantly unravelling his capacity for love by his fear of being seen.

Queer is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV and Amazon Video.