Pablo Larraín | 2hr 3min

Opera singer Maria Callas’ astonishing talent is both her greatest gift and curse in Pablo Larraín’s dreamy, melancholy biopic, giving her reason to live and simultaneously eating her up inside as she navigates the final week of her extraordinary life. “Happiness never gave us a beautiful melody,” she informs the filmmakers creating a documentary about her career. “Music is born of distress and poverty.”

It’s no surprise that a woman who was forced to sing to fascist officers as a child during World War II should attach such negative associations to her craft, yet the self-confessed intoxication she feels when performing nevertheless binds her to this deep-rooted sorrow. Callas is a woman of magnificent contradictions, and it is in the collision between those extremes where the disorientating, nostalgic surrealism of Maria takes form, painting a complex portrait of both soaring exultation and abject misery.

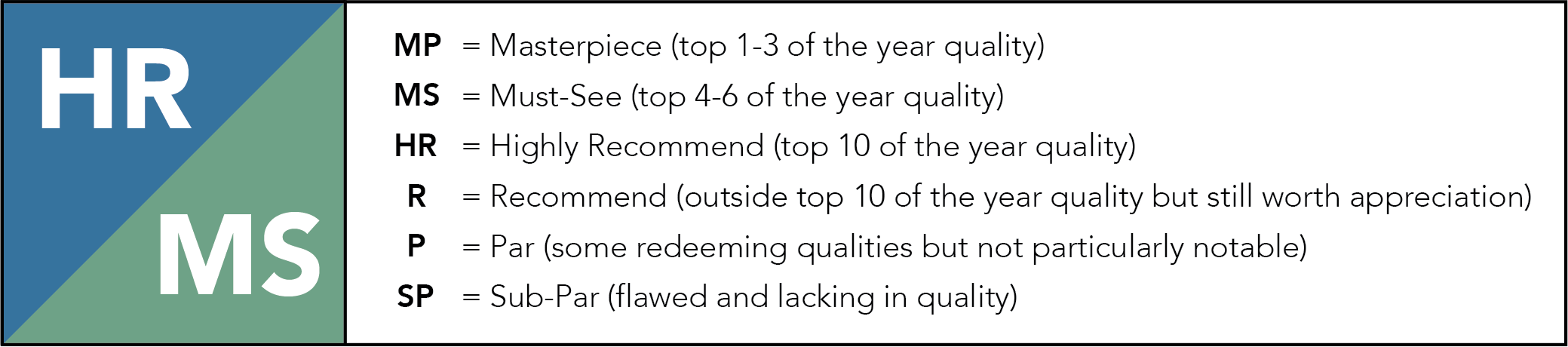

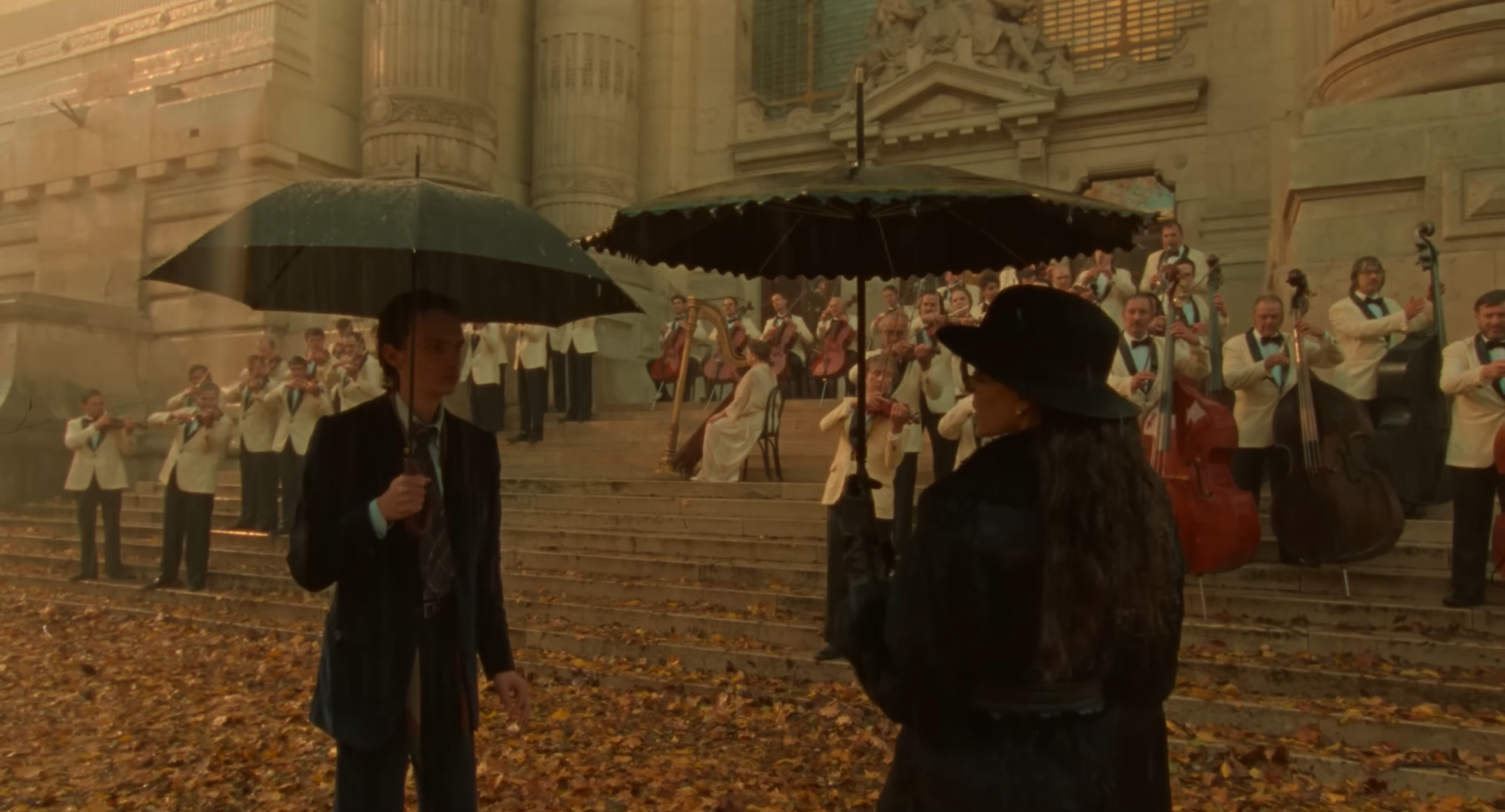

These have been common themes throughout Larraín’s trilogy of historical female icons, beginning with Jackie’s intimate meditation on grief and Spencer’s interrogation of disintegrating identity. In Maria, the Chilean director once again weaves his protagonist’s declining physical and mental health into a fragmented narrative, though this time merging the pensive flashbacks and ethereal hallucinations of its respective precursors. Choruses and orchestras seem to manifest all through Callas’s Parisian wanderings, inviting her to take the stage, while shaky rehearsals are deftly intercut with visions of those elaborate performances that she once delivered to adoring audiences. Even the aforementioned documentary crew is revealed early on to be a concoction of her lonely mind longing for those bygone days of cultural relevance, consuming her in the crushing, psychological isolation of a life in the public eye.

Angelina Jolie’s celebrity status has often been more anchored in her star power than her acting talent, so the delicate vulnerability she displays as an ailing Callas quite easily stands as her finest achievement to date. She inhabits the troubled soprano as a fragile shadow of herself, lingering in a space between life and death where reality fades away and memories flood back stronger than ever. She is visibly pained when listening to her old records, overwhelmed by the musical perfection that her voice will never match again, even as she hopelessly tries to recover it along with her dignity during private lessons. When a resentful fan confronts her over a show that she cancelled years ago due to poor health, she bites back with indignant fury, yet still she carries immense guilt over her inability to live up to the divine, immaculate image of her younger self.

With the accomplished Edward Lachman by Larraín’s side too as cinematographer, Maria develops an elegant visual style to match Jolie’s enchanting aura. There is a touch of Jean Renoir’s poetic realism in the camera’s gentle gliding through her lavish Parisian apartment, using embellished doorways and mirrors as frames for Larraín’s grand production design. One wide shot angled into her living area from the next room over even makes for a gorgeous bookend, setting a stage which effectively turns her passing into an opera.

The handheld camerawork and zooms which mimic the archival footage laced throughout Maria don’t blend so smoothly with the otherwise graceful aesthetic on display, so Larraín is smart to restrain these elements. The shift to black-and-white photography in flashbacks rather stands as the stronger formal contrast to Callas’ present-day story, maintaining its visual majesty while underscoring another sadness which has long been by her side. After leaving her husband for wealthy business magnate Aristotle Onassis, she finds herself swept away by his charm, yet frequently subjected to his imposing demands. She was to reduce her public performances, he decided, and the abortion she got for him had devastating long-term effects on her body. Nevertheless, this is the man that Callas would harbour feelings for her entire life, eventually making peace with him on his deathbed.

That Aristotle would marry Jackie Kennedy following his affair with Callas makes for a fascinating plot point in Maria, if for no other reason than the connection Larraín is consciously drawing to the first film in his unofficial biopic trilogy. While JFK is played by Caspar Phillipson, reprising his role from Jackie, the beloved First Lady influences the narrative entirely offscreen. Callas regards her with reverence and even a bit of jealousy, going out of her way to avoid crossing paths so that she needn’t face her former lover’s wife. The fact that these two distinguished women should be caught in each other’s orbits only further enriches Larraín’s framing of Callas’ life, constantly trying to measure up to a standard of sublime feminine grace that always seems out of reach.

Clearly this pressure takes a physical toll on Callas as well, inflicting drug addictions, eating disorders, and strained vocal cords which inhibit her singing. Although she tries to sustain hopeless fantasies of a thriving career, it is only in understanding the root of her nostalgia that she is able to salvage the residual beauty of her art.

“My mother made me sing. Onassis forbade me to sing. And now, I will sing for myself.”

As she stands by her apartment window and delivers a final, aching rendition of ‘Vissi d’arte’ from Puccini’s Tosca, she once again connects to that joy and sorrow which fuelled her passion for many years. “I lived for art, I lived for love,” she exults in Italian, while begging for a heavenly answer to her lonely prayer.

“In this hour of grief, why, why, Lord, why do you reward me thus?”

Larraín is not one to end his biopic with expository text spelling out his subject’s legacy. Maria’s blend of archival film and ethereal impressionism paints a far more complete, evocative portrait of the legendary prima donna than any biography ever could, framed in a fleeting moment of vulnerability when her tormented soul was thoroughly exposed. There within the dimming spotlight, where art is produced solely for its creator, the liberation it ushers in is enough to release the most weary, forsaken artist from a lifetime of agonising perfection.

Maria is currently playing in theatres.