Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 24min

Looming large over the rundown homes of Tokiko’s village in Tokyo, an immense, round monolith of metal beams dominates the skyline. Unlike the smokestacks and factories which dot these urban outskirts, its purpose remains unclear – perhaps it is scaffolding for some postwar reconstruction, or maybe it is an abandoned industrial project. As far as Yasujirō Ozu is concerned, its function is not as important as the immense symbol of oppression it imposes upon those living in its shadow. It may fade into the background at times, blurred through his shallow focus, but it never disappears entirely from view. Even when Tokiko carries her ailing infant son Hiroshi through town streets, there it is right behind her, rising up in a low angle tracking shot as she desperately seeks help.

The year that neorealism peaked in Italy, Ozu was centring this hulking, industrial structure in his own examination of postwar poverty and its debilitation of the marginalised working class. There was no time to sit and mourn the great losses that were suffered from World War II – society simply needed to move on, leaving behind women like Tokiko whose enlisted husbands had not yet returned from war. Options are consequently limited for Tokiko, and as A Hen in the Wind sees her driven into a dire corner with rising inflation, Ozu offers nothing but incredible sympathy for the unfathomable choices she must make in extreme circumstances.

“There’s an easier way for her to live,” Tokiko’s neighbour Orie slyly suggests one day, indirectly planting the idea of prostitution to pay for Hiroshi’s exorbitant hospital bills. It is telling that Ozu lines the bottom of the frame here with empty sake bottles, underscoring another set of struggles altogether within Orie’s home. She may be a minor character, but she is fully detailed in her short screen time, hinting at the nihilism which may similarly consume Tokiko in her reluctant turn to sex work. Hiroshi is all that matters, and as she examines her tired expression in the mirror, Ozu sombrely cuts between her face and its reflection. She knows what must be done, and in compromising moral dignity for an abiding love of her son, Kinuyo Tanaka’s performance manifests a tragic, pitiful sorrow.

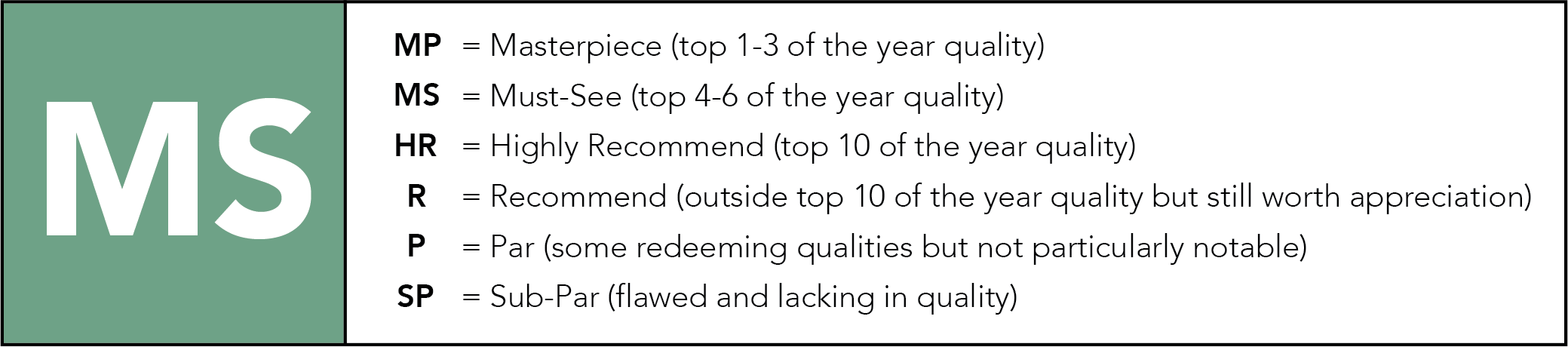

Of course, Ozu would never be so explicit as to reveal Tokiko at her most compromised. A string of pillow shots transition into the shady local establishment where prostitutes meet their clients, settling on smoking ash trays, futons, and low-lit corridors, before meeting a group of patrons and staff playing mahjong. Their brief conversation fills in the gaps, revealing that Tokiko decided to only spend a single night working at this brothel, before Ozu poetically bookends the scene with identical pillow shots in reverse order.

Tokiko’s plea for her friend’s understanding cuts right to the heart of this undignifying dilemma, and through Ozu’s front-on camera placement, it virtually resonates as a plea to the viewer as well.

“If you were a woman with no money and your child got sick, what would you do? Where would you get the money for the hospital? What else can a woman do?”

The wait for her husband Shuichi’s return from war is made all the more agonising for this betrayal, overwhelming her with guilt as she speaks to his framed photo. Still, the shame felt upon his actual arrival may be even worse. From here, Ozu follows Shuichi’s tormented search for answers to his wife’s infidelity, hoping to find within himself the ability to forgive her. Visiting the brothel where she worked, he begins by finding some sympathy for a young prostitute whose elderly father and school-age brother financially rely upon her. With their conversation set against a view of distant cargo ships and industrial bridges, we are reminded of the harsh realities that consume these unlikely companions, yet which ultimately grants them a mutual understanding of each other’s difficult circumstances.

The scraps of junk metal which dot this lookout not only serve to further underscore these poor conditions, but also become the subject of Ozu’s recurring pillow shots, handsomely framing backgrounds through hollow, rusted barrels. At a certain point, they even draw Shuichi’s focus as he wanders alone, pensively considering society’s abandoned litter alongside his own personal problems. A Hen in the Wind moves with him along this meditative journey, giving him that familiar low angle tracking shot which previously captured his wife and child against the monolith, and building out underlying formal patterns which echo particularly strongly at its climax.

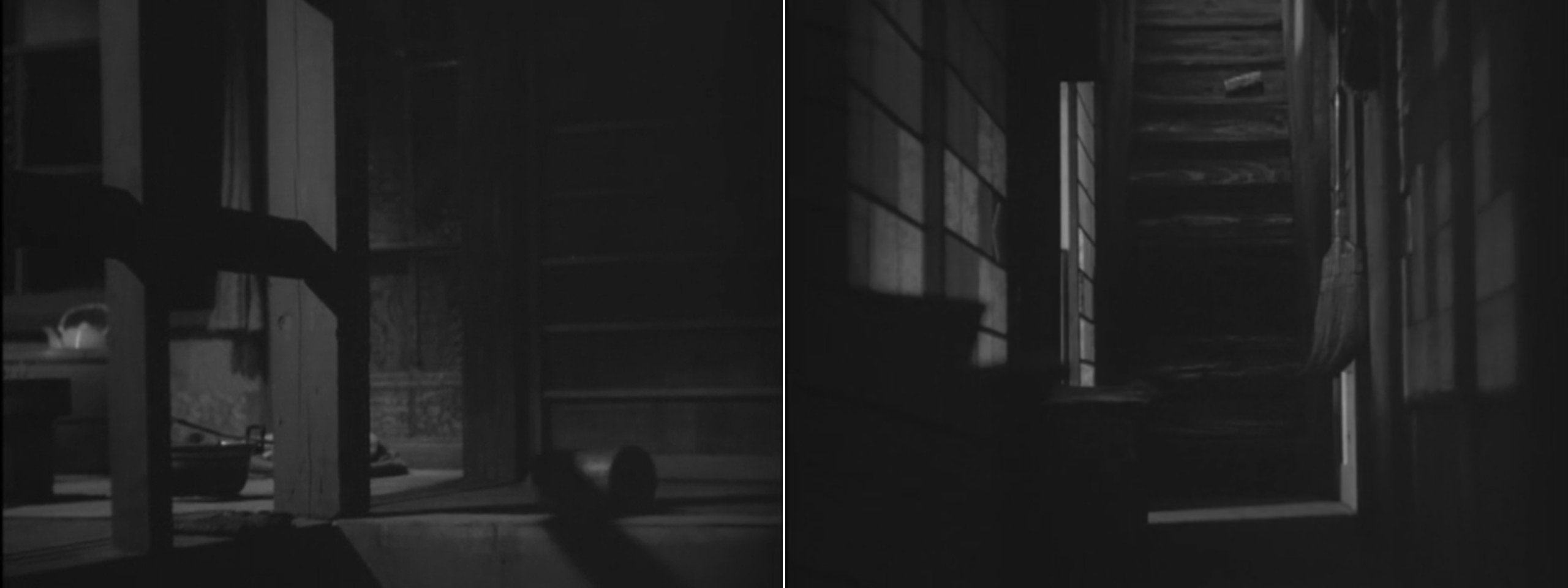

The initial setup arrives in a confrontation between the two when his heated questions completely shut her down. Frustrated by her refusal to speak, he throws a can down the stairs in a fit of anger, and Ozu momentarily departs from the scene with a cutaway to the ground floor where it eventually stops. Taken alone, this fleeting pause lets us grasp the pain which quietly lingers in the wake of Tokiko and Shuichi’s altercation, though its return in an even greater outburst also reveals it to be an accomplished piece of foreshadowing. As Tokiko ashamedly clings to him with profuse apologies, she is met with a callous shove that incidentally sends her tumbling down the stairs – and Ozu does not miss the chance to recall the exact same shot from earlier. In the silence which follows, she lies motionless in the same spot where the can once rested, crumpled and dehumanised by the comparison. Ozu very rarely uses physical violence in his films, but when he does it evidently carries the power to shatter entire worlds, fracturing the foundations of his characters’ humble lives.

Yet somehow, even at Tokiko and Shuichi’s lowest, Ozu does not lose faith in the redemption of their souls. It takes a forced confrontation with the impact of his own behaviour for Shuichi to recognise where this cycle of resentment must end, and where healing between husband and wife must begin, putting each other’s transgressions behind them. Just as Japan must rebuild after the war, so too shall these aggrieved lovers piece together the remnants of their once-happy lives, finding whatever joy can survive beneath the shadow of that featureless monolith. There in the closing shots, children harmoniously play at its feet, and for the first time A Hen in the Wind reveals a fragile renewal lifting the historical weight of sacrifice, shame, and an entire generation’s moral compromise.

A Hen in the Wind is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.