-

The Thin Red Line (1998)

There is a jarring contrast between Terrence Malick’s violent imagery and his affecting spiritual expressions in The Thin Red Line, but it is exactly this disparity upon which he hinges his condemnation of war as an ugly stain on the natural world, playing out the human struggle between dominance and grace through stirring, lyrical rhythms.

-

Yi Yi (2000)

The oscillation between isolation and intimacy is just as much a part of life’s cycles as the births, marriages, and deaths that the three generations of the Jian family experience through different lenses, but while these occasions lay the foundation of Yi Yi’s grand formal structure, Edward Yang spends much of the film chasing the…

-

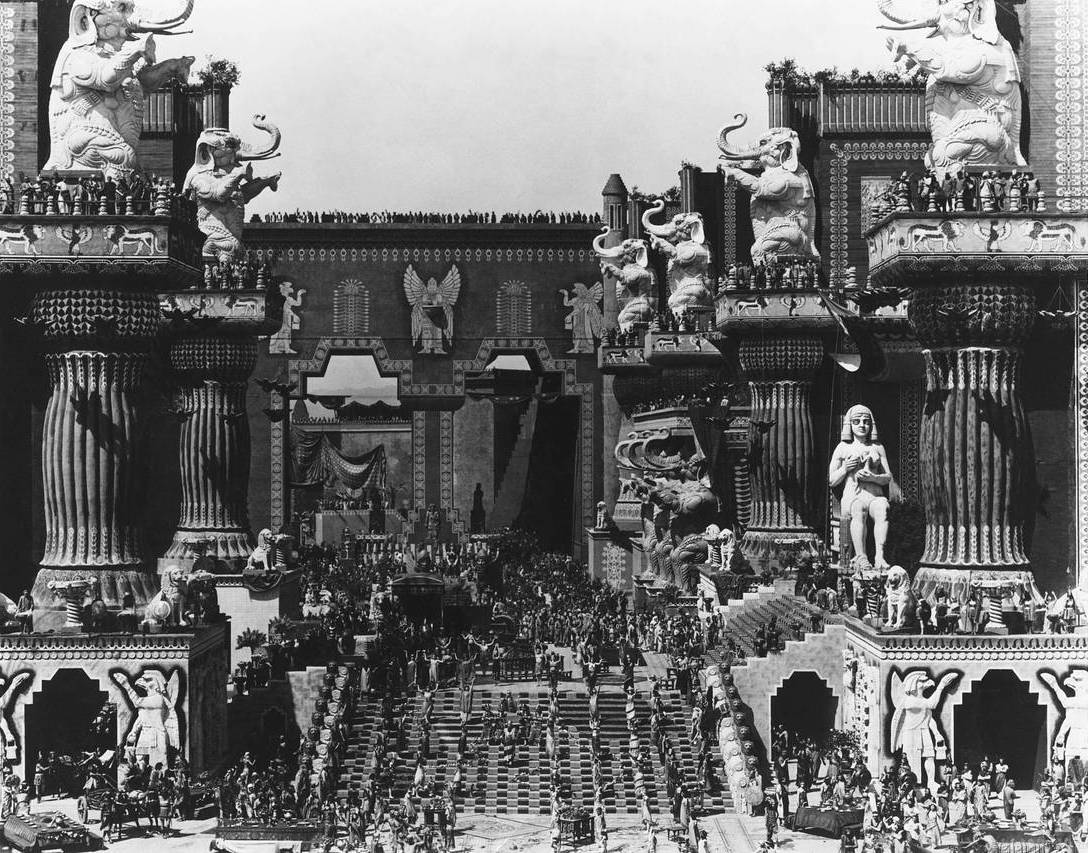

Intolerance (1916)

In wrapping up four parallel fables of prejudice stretching from ancient Babylon to the twentieth century, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance masterfully orchestrates cycles of human redemption and transgression with joy and sorrow, layering plot threads and symbolic counterpoints like intricate harmonies through this epic, cinematic experiment of narrative structure.

-

Elvis (2022)

In piecing together artefacts of Elvis Presley’s inspiration and influence littered throughout the past century, Luhrmann melds anachronistic music, wildly kinetic camerawork, and imaginative editing together into a vibrant collage of immense artistic passion, effectively adopting the rockstar’s own form of rebellious creative expression.

-

The Birth of a Nation (1915)

Through the hundred or so years of feature narrative films, The Birth of a Nation may indeed be the singularly most abhorrent work to hit such ambitiously artistic heights, as D.W. Griffith singlehandedly defines the artform with astonishing displays of intercutting and jaw-dropping set pieces, while exposing the depravity baked into the history of nationalistic…

-

Delicatessen (1991)

Within Delicatessen’s grotesque, dystopian France that sees a butcher kill his neighbours to sell their meat, Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro construct a meticulously expressionistic world of absurdly outlandish set pieces which, while unsettling in their Gothic visage, savour the traces of whimsy that exist on the verge of extinction.

-

Blue Velvet (1986)

Blue Velvet could be read as a twisted coming-of-age film in its discovery of worlds and minds that are not what they seem, though the depths that David Lynch plunges into humanity’s psychosexual awakening, disconcerting iconography, and bold colour palettes places it in a surreal class of its own, digging through the veneer of suburban…

-

Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

In the dreamy, non-linear structure of Once Upon a Time in America’s epic narrative that covers the full scope of one Jewish gangster’s life in twentieth century Manhattan, Sergio Leone deftly blends each era within a single brew of nostalgia and shame, sifting through the mythology of a nation in the midst of squandering the…

-

Trafic (1971)

Trafic may not possess the sheer ambition of Jacques Tati’s previous films, but his resourcefulness remains remarkable, uncovering rich satire in recognising that the attempts of drivers trying to get somewhere while helplessly sitting in stagnant crowds of high-tech, metal boxes may be the ultimate paradox of an inept modern society.

-

Eastern Promises (2007)

Even as David Cronenberg drifts away from explicit body horror and towards suspenseful crime drama in Eastern Promises, his camera never wavers from bloody acts of carnal violence, nor does it falter in its study of those symbolic tattoos which mark the skin of gangsters with their personal histories, mutilating their identities to fit the…

-

A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

Edward Yang’s mastery over cinematic realism is absolutely essential to the heartrending authenticity of A Brighter Summer Day, carefully examining the overlooked tragedies of Taiwan’s modern history through a lens that seeks genuine understanding of its aching sorrow, and exploring the many facets of its social strife in virtually every frame.

-

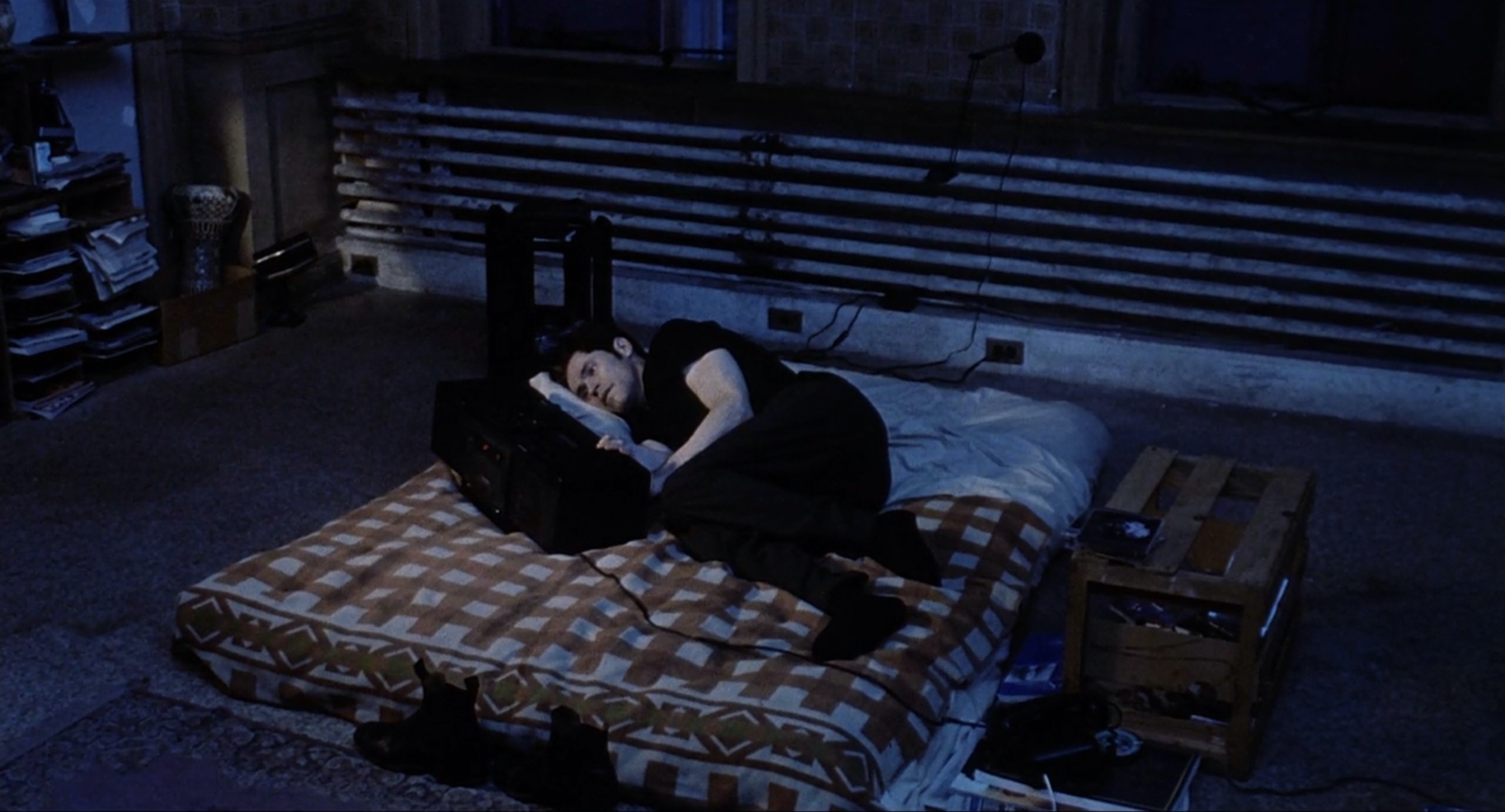

Light Sleeper (1992)

The guilty paradox of lamenting New York City’s moral decay while actively contributing to its degradation as a drug dealer eats away at insomniac John LeTour in Light Sleeper, and within Paul Schrader’s complex character study of shame and atonement, it evolves into a self-aware melancholy, reconsidering the unsavoury direction his life has taken.