Jean-Luc Godard | 1hr 45min

When we initially land in the bizarre modern landscape of Weekend, it appears as if civilisation is standing on a precipice, tentatively waiting to tip over into absurdist anarchy. When cheating lovers Corinne and Roland eventually hit the road, it quickly becomes clear though that this is not the case – as far as Jean-Luc Godard is concerned, society is already there, consumed by its own avarice and hubris. Together, both spouses intend to claim their inheritance from Corinne’s parents, though privately they also plant to murder each other afterwards and greedily take more than what is rightfully theirs. By every economic, political, and social metric, they are the most standard definition of twentieth century bourgeoisie, self-absorbed in their materialistic mindsets while naively unaffected by the disaster unfolding around them. It is only a matter of time before they too are brought down to the grotesque level of squalor that those below them have been suffering through for their entire lives.

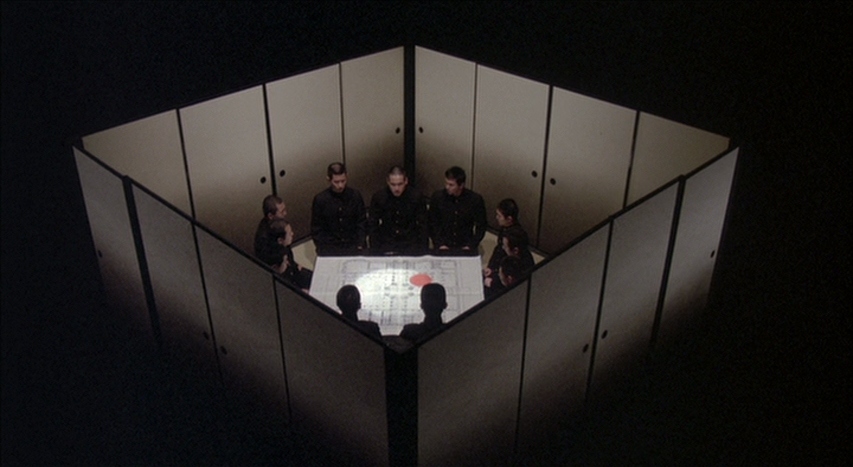

Coming out at the tail-end of Godard’s magnificent run of postmodern films in the 1960s, Weekend also signals a more politically-inclined direction for the French auteur that would last several more decades, yet would never reach anywhere near the heights of his early career. For now though, his Marxist-Leninist ideals that had previously only touched the surface in films like La Chinoise emerge fully formed here, coalescing almost flawlessly with his radical formal artistry.

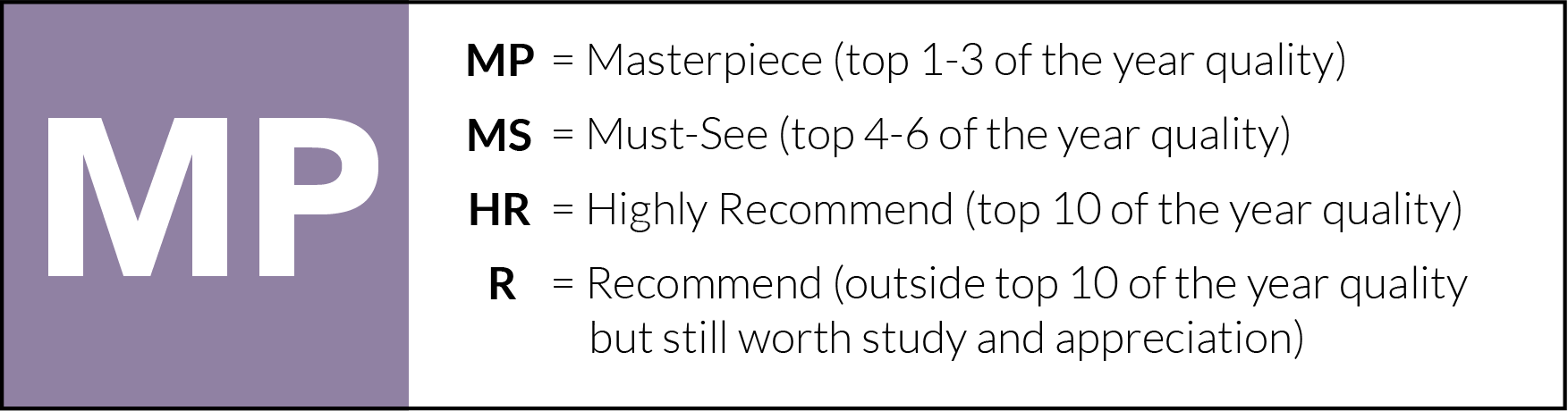

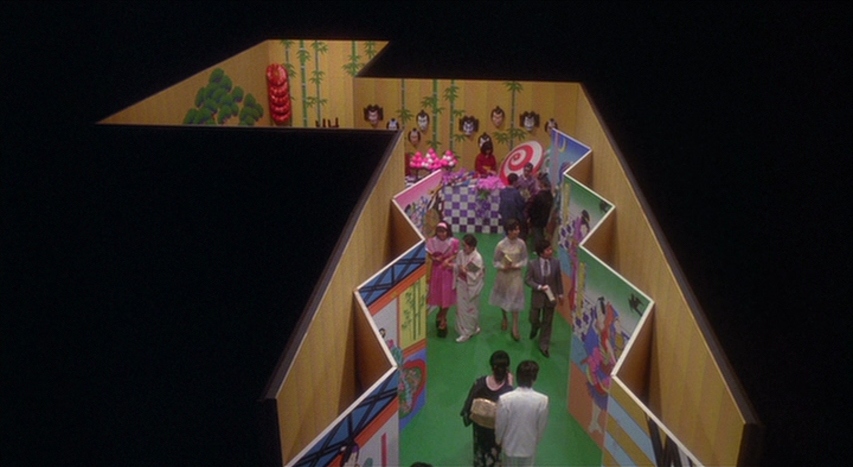

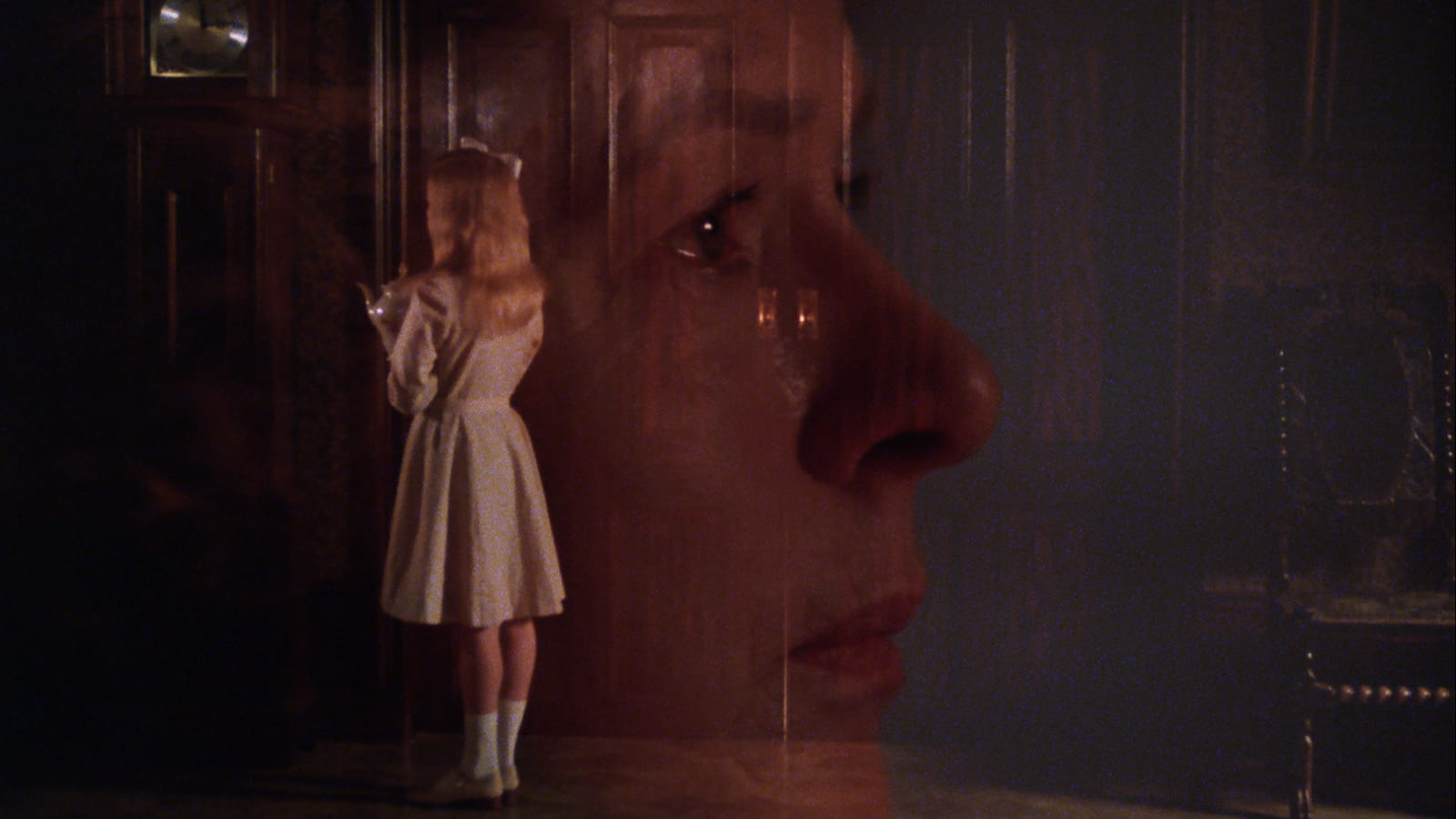

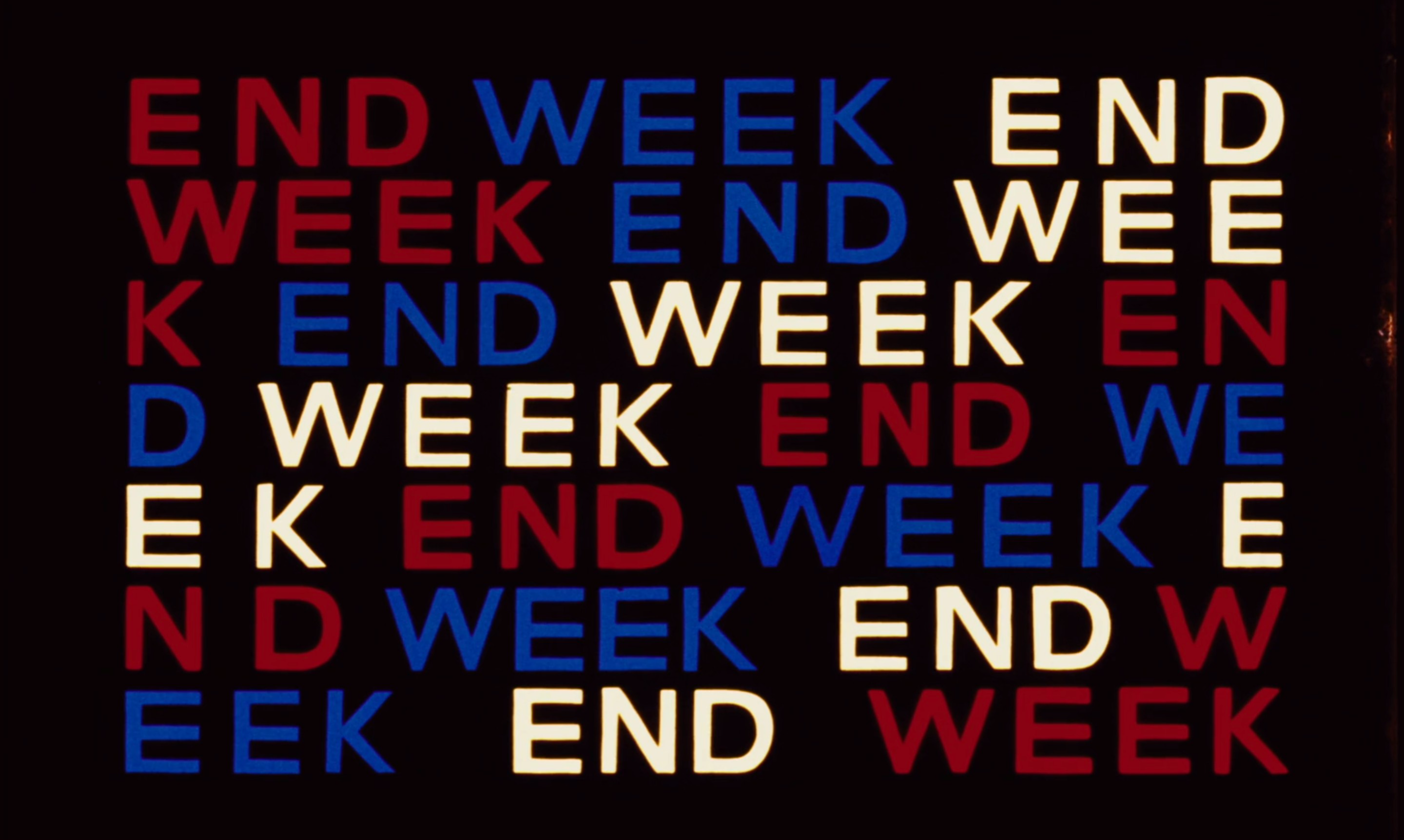

As it is, Weekend marks the last true masterpiece of the French New Wave, subversively making as much a target out of the socioeconomic conventions of 1960s France as the medium of film itself. The two cannot be separated in Godard’s post-ironic deconstructions, purposefully muddling his love of cinema with his impulse to pull us from its emotional grip, rip it apart, and expose it as little more than a two-dimensional illusion of light flickering on a screen. The sporadic intertitles that interrupt its narrative and rhythmic flow are an integral part of this, romantically describing this work of cinema early on as “A film adrift in the cosmos”,before almost immediately eviscerating itself with a far more self-deprecating reproach – “A film found on a dump.” When civilisation comes crashing down as it has in Weekend, art holds very little significance, and yet even within these contradictions Godard still can’t help cherishing the creative expression it grants him.

He is evidently not the only one trivially obsessed with pop culture in the midst of an apocalypse either, with a faction of rebels taking the titles of classic films as their code names – “Battleship Potemkin calling The Searchers” – while writer Emily Brontë and French revolutionary Louis Antoine de Saint-Just surreally wander through anachronistic vignettes. Like all of Godard’s greatest films, Weekend is an eclectic pastiche of both recognisable and obscure icons, embracing the inevitability of artistic theft while demonstrating the possibility of still creating something valuable and original. Incredible artistic feats such as this are all too scarce in an era of dull cliches, refusing to see the potential of pre-existing material to build anything other than soulless nostalgia, and it is this stubborn passiveness on a more universal scale which damns the French society of Weekend to its dystopian grave. These citizens who seem to be driving nowhere in particular would much rather tear each other down with violent, petty road rage than continue towards their destination.

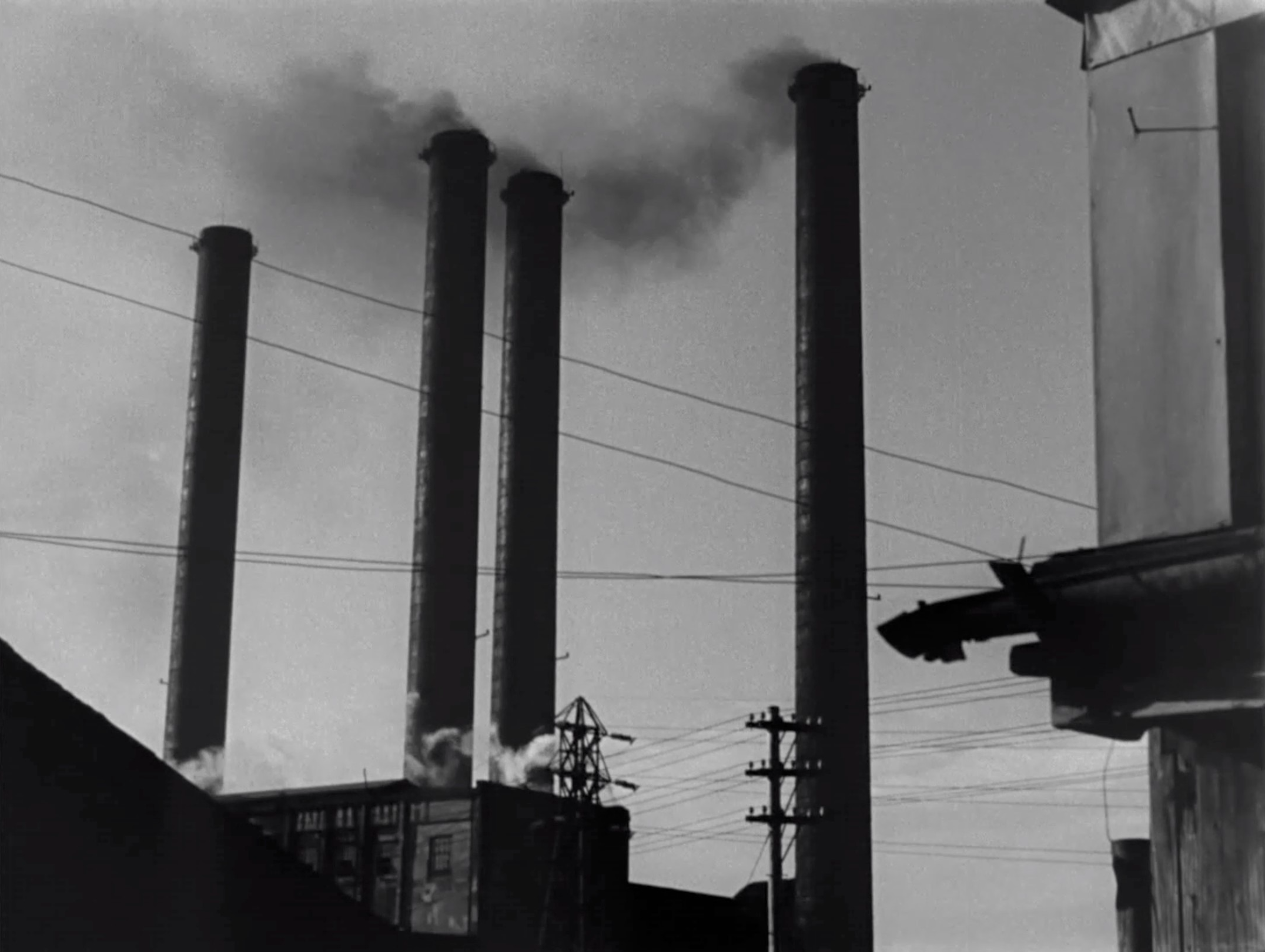

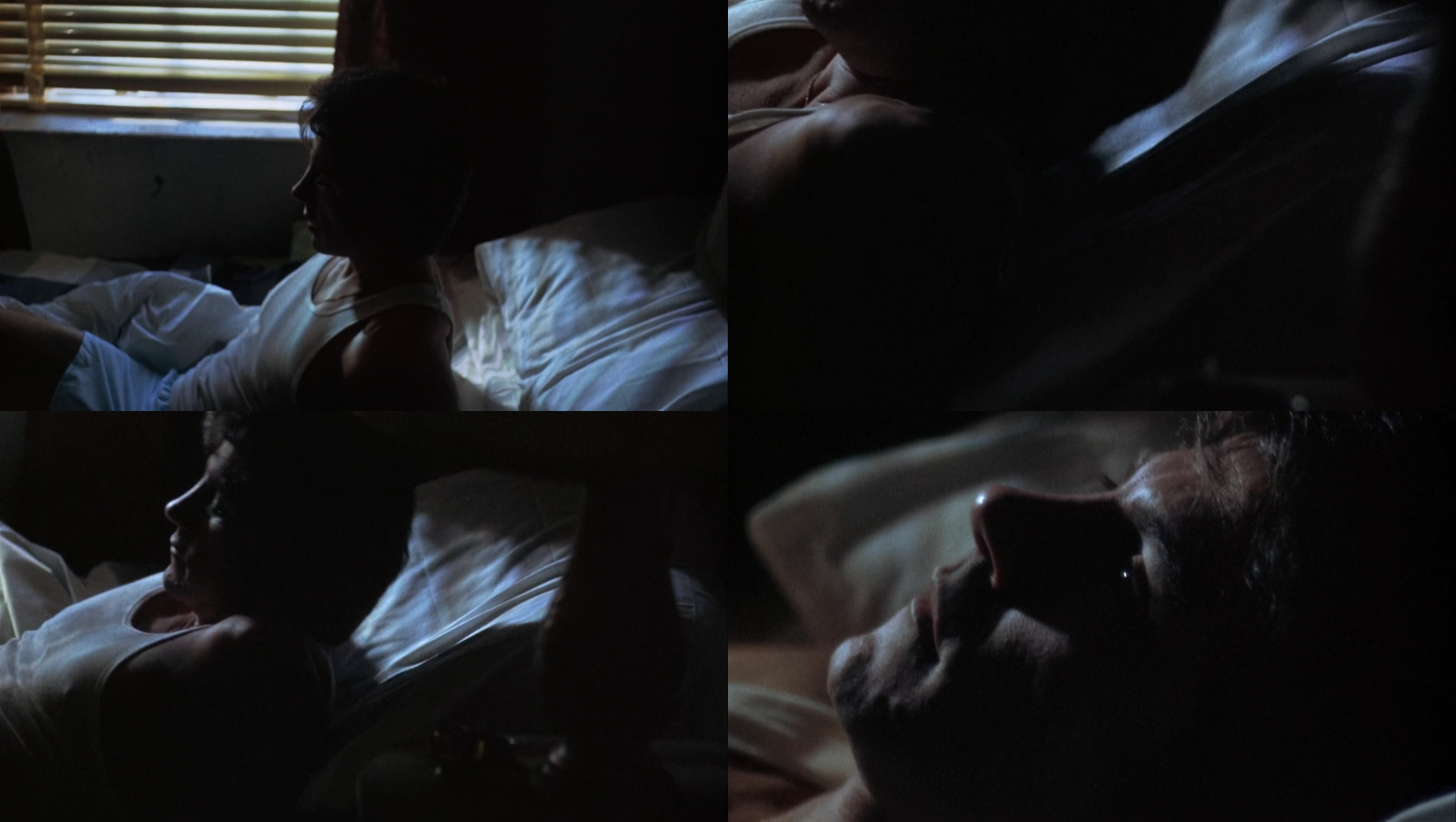

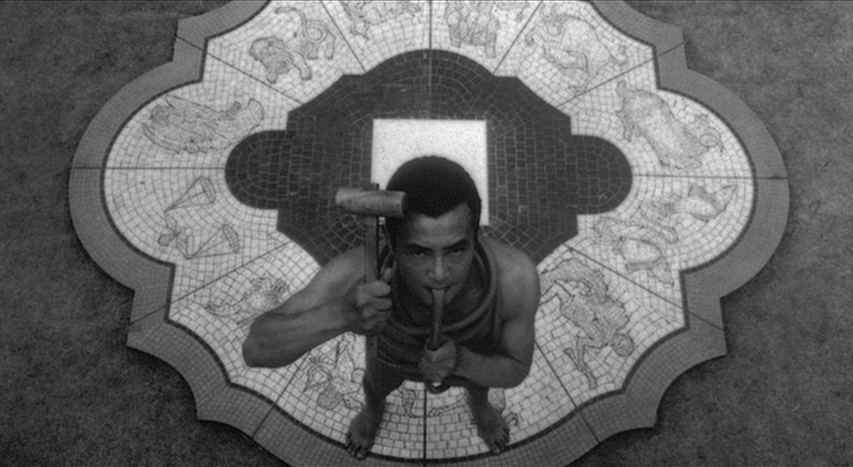

When motorists aren’t furiously wielding tennis racquets and rifles over their crashed cars, it is more than likely that we will instead find them stuck in endless traffic jams, thus forming another visual metaphor that Godard saturates with Kafkaesque insanity. In one of the defining shots of his career, the camera tracks from left to right along a string of cars on an open country road while Corinne and Roland roll comfortably down an empty lane, skipping the inconveniences that lower classes must suffer through. A cacophony of perpetual beeps screams through the air, doing little to ease the congestion which grows progressively stranger the further along we travel.

A man and a boy throwing a ball between cars, a vehicle turned completely upside down, a truck of monkeys making an escape, a horse and wagon standing atop a pile of faeces, an elderly couple playing chess on the road – for eight minutes, Godard drags us through tableaux of trivial nonsense, revealing the time-wasting frivolity that grows from a lack of forward movement. In case we become too comfortable in the offbeat rhythms of this long take, he cuts in a couple of timestamps indicating the minutes that pass from 1.40pm to 2.10pm, and he also irrationally loops back on the same cars a couple of times as well. We shouldn’t be surprised to find what is causing the holdup at the end of the traffic, but it is shocking nonetheless. A bloody, violent collision has streaked the road with blood, and left the corpses of adults and children lying on the roadside.

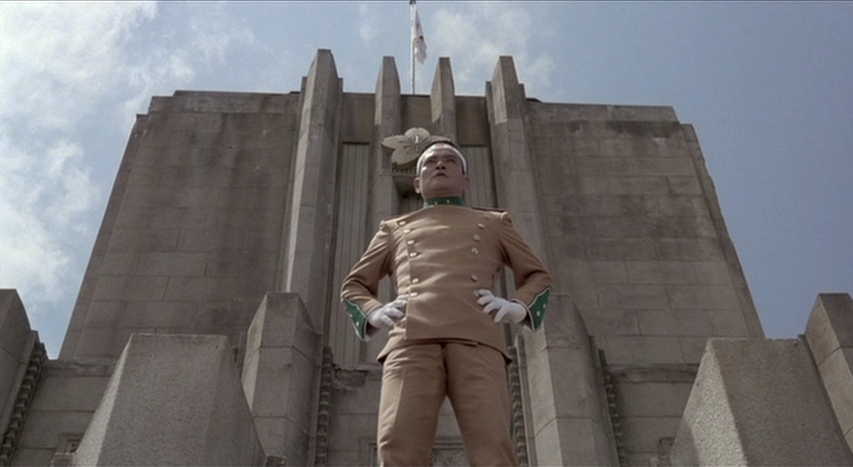

These cars may have once been proud emblems of modern industry and progress, and yet in Weekend they prove to be nothing more than pathetically inept status symbols, superficially signifying one’s wealth before perishing and potentially destroying their owners along with them. What starts as a biting gag in the film’s opening minutes gradually evolves into a dark formal motif, as well as a colourfully derelict part of Godard’s daunting wastelands bizarrely littered with burning vehicles. When his characters aren’t stealing clothes from dead bodies, they rarely give these a second look.

The only time we even see a collision in action rather than just the aftermath is when Corinne and Roland eventually lose their car in one, and yet even here Godard does not seek to capitalise on salacious thrills, instead wishing to remind his audience of the hollow artifice in such gratuitous spectacle. As our central couple lose control of their car, the film reel and projector appear to malfunction as well, chaotically slipping the image offscreen before stabilising on the image of the subsequent fiery wreck. At first, we might think that the bloodcurdling scream coming from the debris might finally offer us sincere, personal stakes, until we hear the shrieking woman cry out the source of her horror.

“My Hermès handbag!”

Even when the world is crashing and burning, the bourgeoisie will only begin to panic when those material luxuries that dull the existential pain are lost. When they’re the ones hitchhiking on an open road and begging for help, they also find out very quickly how hypocritical their own kind are. “Are you in a film or in reality?” one woman stops to ask. “In a film,” Roland responds, clearly giving the incorrect answer as the would-be good Samaritan drives off. Two more drivers also pull over to check the superficial political alliances of this stranded couple. “Would you rather be screwed by Mao or Johnson?” one of them inquires, before decisively making up their prejudiced mind when Roland chooses Johnson.

“Drive on, Jean. He’s a fascist.”

These petty political divisions may be even more insidious than those instances of road rage we witness elsewhere, elevating a shallow commitment to political ideals above moral goodness and survival. For as long as Godard is delivering commentary such as this with his usual creativity and wit, Weekend continues to move along to its own unpredictable rhythmic dissonance, and yet the point at which he stops the film in its tracks to linger on a political speech is far too plain to be considered inspired on any cinematic level. The highlight reel of previous scenes that he intermittently cuts in over the top does little to offset the dryness as well, marking a serious blemish on what is otherwise a masterpiece of post-classical filmmaking.

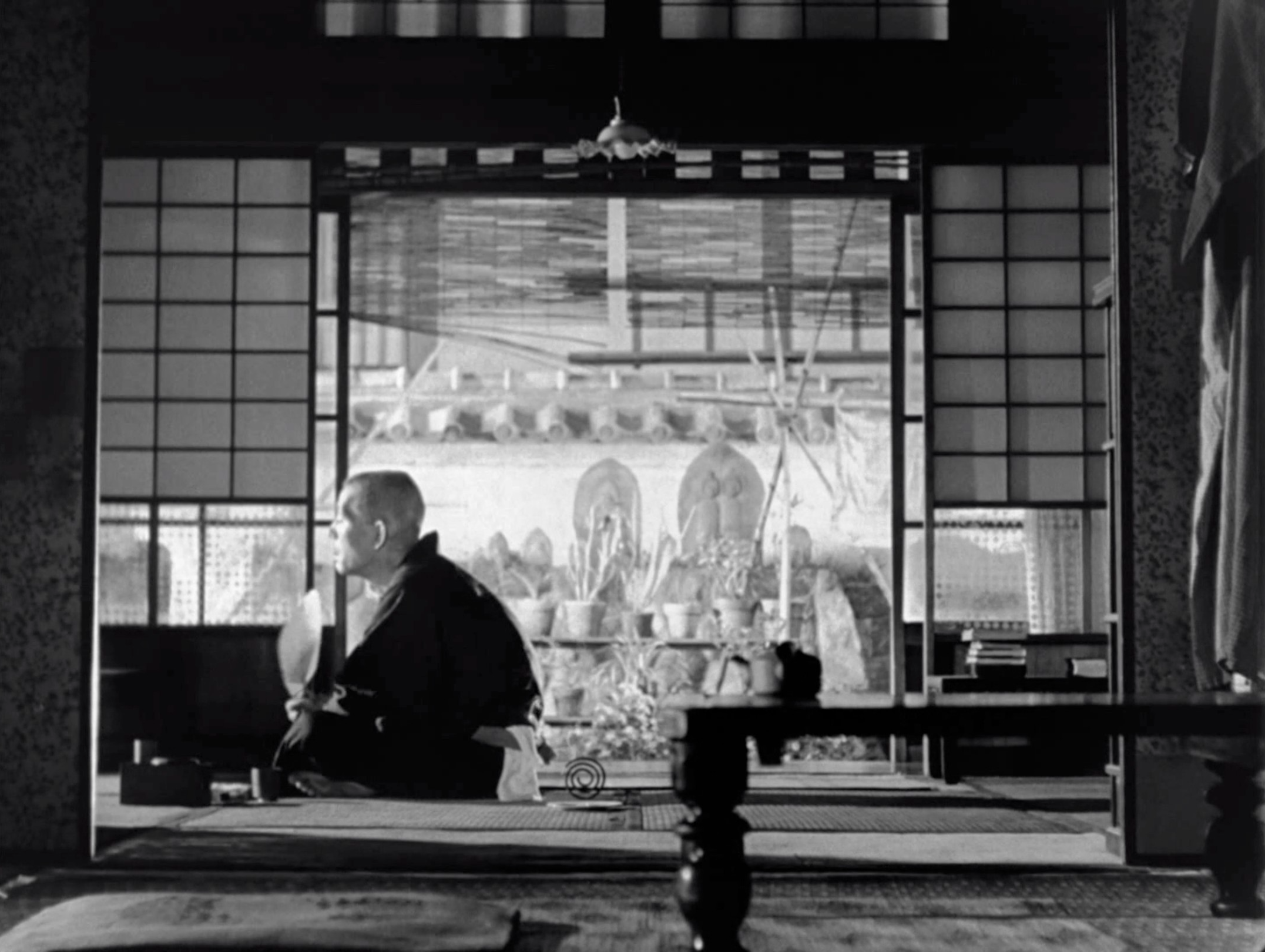

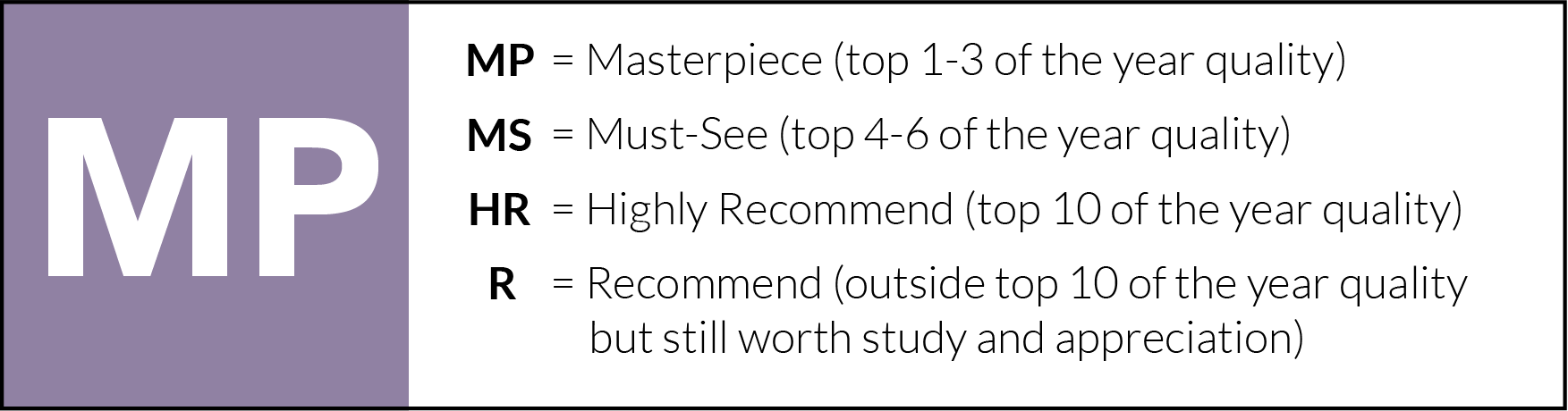

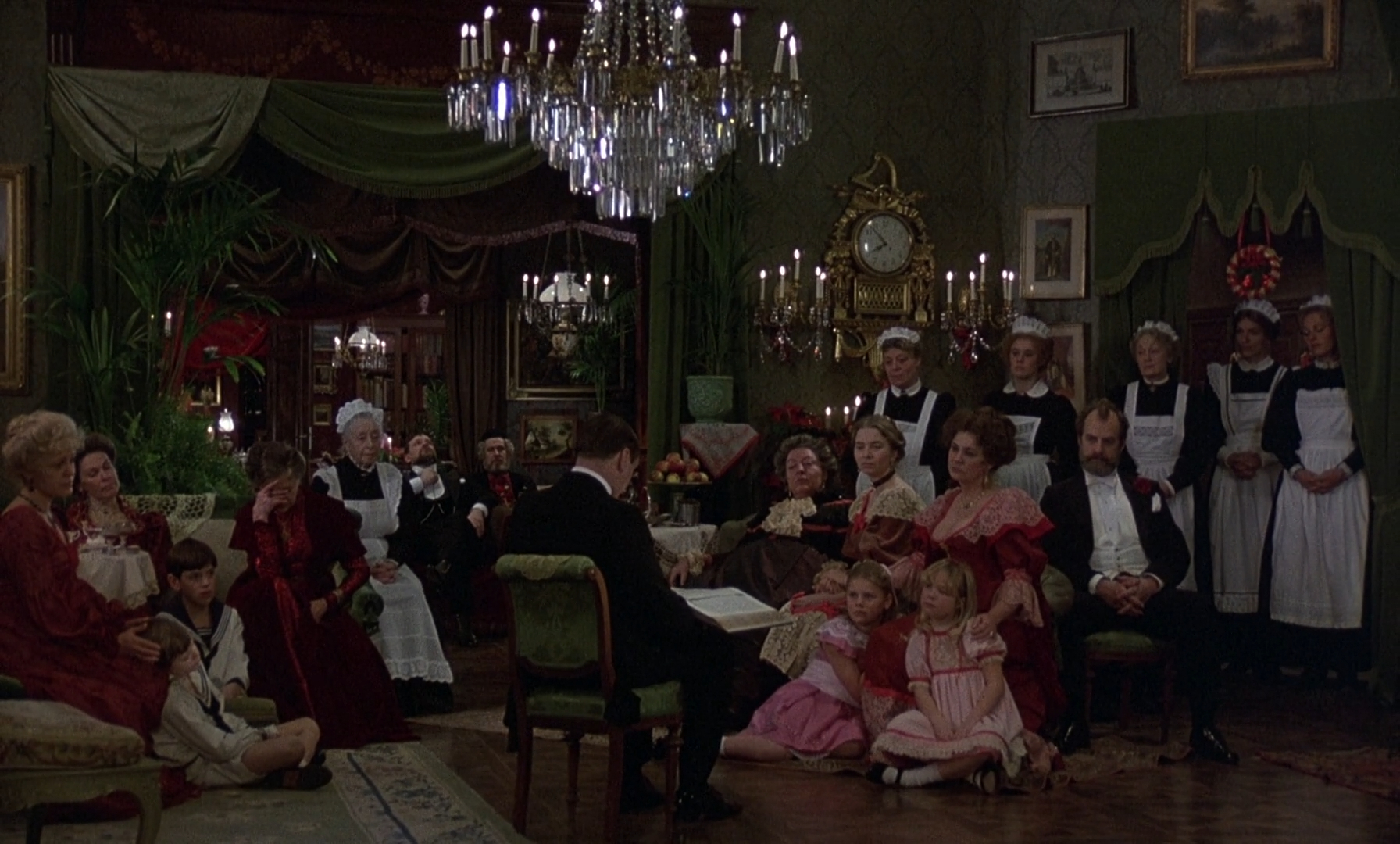

On one hand, it is tough to imagine a slightly younger Godard from the early 1960s carelessly falling back on a scene like this, though by nature of his dynamic, ever-changing style, such variation also comes with the territory of artistic innovation. After all, the long takes that appear throughout Weekend are not something we had seen from him before either, and yet they are constantly used to much more brilliant effect here as we wander environments in tracking shots and 360-degree pans. They are superbly controlled in their execution, pushing in and out on Corinne and Roland’s silhouettes early on as she erotically describes an affair, and elsewhere holding an air of constant surprise as Godard slowly reveals a mishmash of incongruent vignettes – a man playing drums off to the side in a forest, for instance, or the bored spectators watching a farmer play Mozart. Like the director himself, he too is holding onto his own irrelevant form of artistic expression while an indifferent society collapses around him.

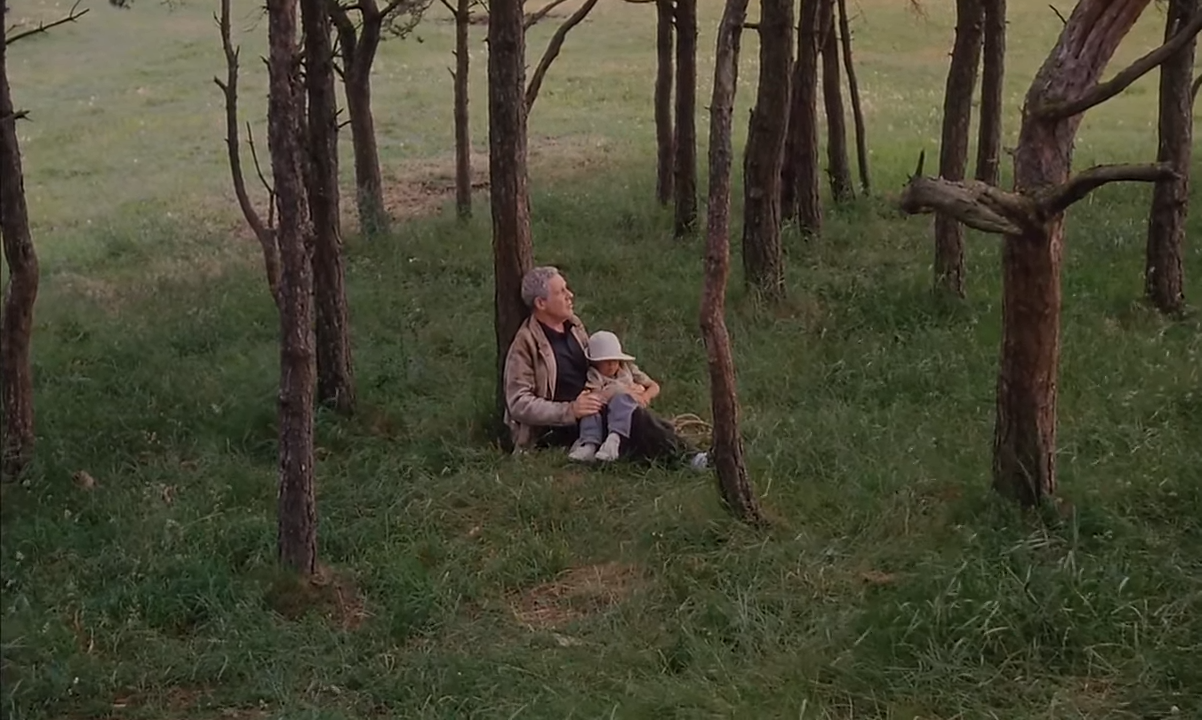

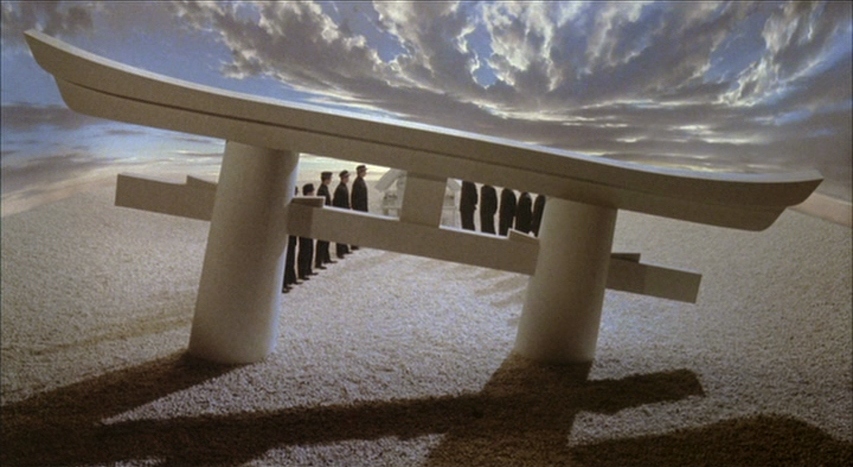

On an even broader level, it is also thanks to these long camera movements that Godard’s apocalyptic world feels so expansive, not so much aiming to establish any rigorous internal logic within it than to create the impression of a giant, meaningless odyssey. After all, was this catastrophic journey really worth the money at the end? Our two spoiled adventurers might think so at first, even going so far as to kill Corinne’s mother when she refuses to hand it over, though their success is cut short when this anarchic wasteland rears its ugly head one last time, landing them in the hands of violently radical hippies. Roland is gruesomely disembowelled – “The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome by more horror,” they explain – and Corinne doesn’t think twice to join in cannibalising her husband when she gets hungry. It is an amusingly out-of-left-field move from Godard to end this absurdist critique of consumer society by watching it ultimately devour itself, but if there is any consistency to be found at all within the sprawling chaos of Weekend, then we can at least reliably expect these vain, pampered materialists to be the source of their own inexorable ruin.

Weekend is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the Blu-ray or DVD can be purchased on Amazon.