Emerald Fennell | 2hr 7min

Whoever or whatever Oliver Quick may be in Saltburn, he is not human. He wears the skin of a lower-class outsider from a troubled family, but his instincts are sharp like a spider’s – or perhaps he is a moth banging up against a window, trying desperately to infiltrate the wealthy Catton family who he is staying with for the summer. “Lucky for you I’m a vampire,” he purrs to Venetia Catton as he grotesquely licks her period blood off his fingers, and when he suits up for an Oxford ball, a classmate lightly jokes that he’s almost passing for “a real human boy.” Perhaps his eccentric hosts sense some animalistic depravity in their son Felix’s new friend, though for the time being they are happy to keep him around like a trophy proving their own generosity.

Emerald Fennell’s follow-up to Promising Young Woman delivers yet another subversive interrogation of power and privilege, and yet Saltburn proves to be far more obscure in its formal construction than that tightly plotted revenge thriller, layering mysteries upon secrets within the titular country estate. With a strong set of creature metaphors at her disposal, Fennell weaves a monstrously sinister fable around Oliver, stealthily wandering through a maze not unlike that which sits in the Catton family’s enormous garden. To those souls unfortunate enough to reach its centre, a giant minotaur sculpture awaits, frozen in the act of ripping apart a victim as it proudly bears its naked manhood. The visual parallels between this mythical creature and Oliver in his truest form are striking – in the absence of wealth and social influence, sex becomes his greatest weapon, and clothes are shed to reveal the aggressive masculinity lurking beneath.

Through Fennell’s elegantly dynamic camerawork, we too find ourselves trapped in these characters’ magnificent habitats, following behind them in three long tracking shots which formally mark our introduction to Oliver, our introduction to Saltburn, and the brilliantly twisted final shot of the film. Especially in the latter two, Fennell relishes the classical architecture and production design that could be straight out of Pride and Prejudice, traversing cavernous ballrooms and lavishly decorated corridors that essentially form a maze of their own.

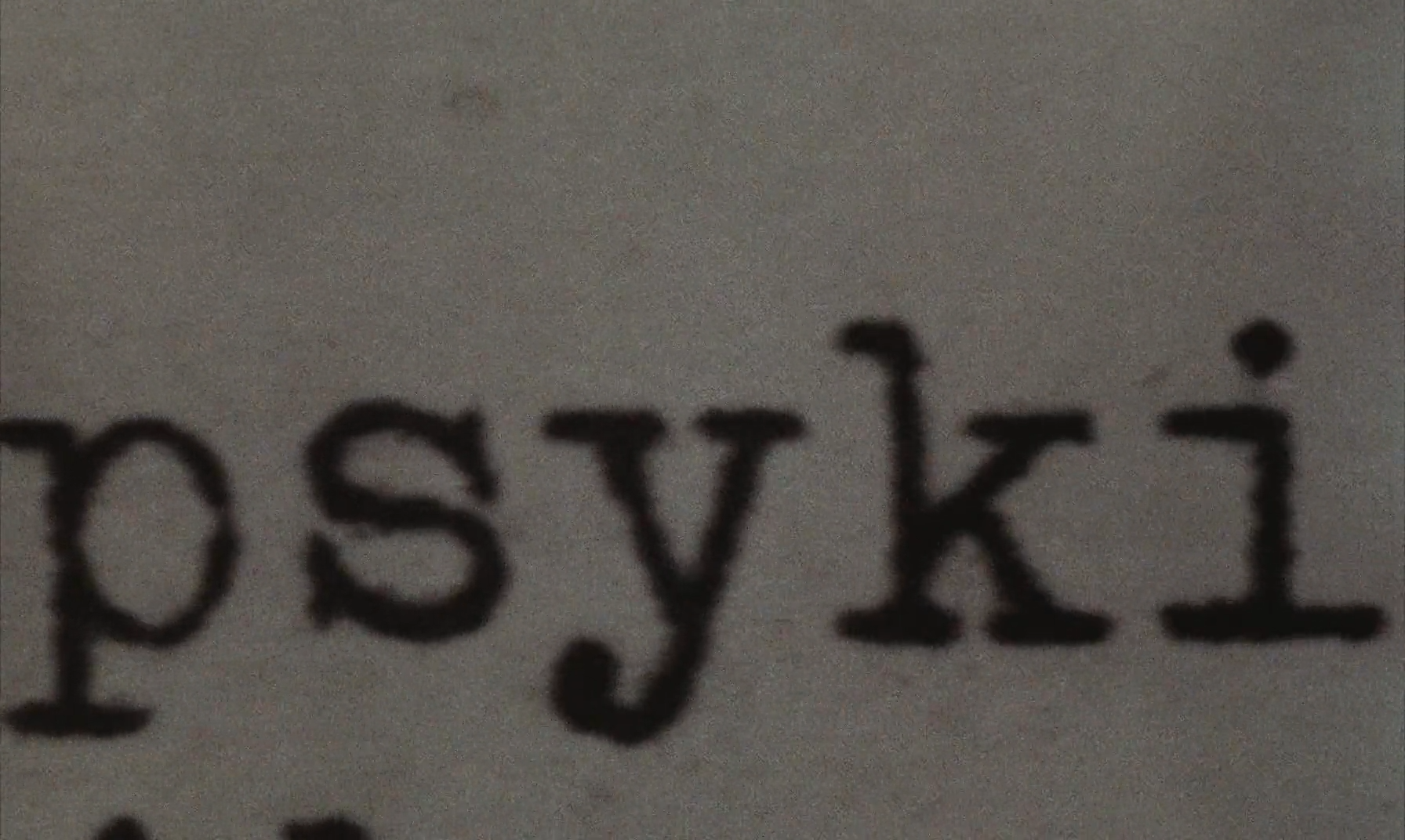

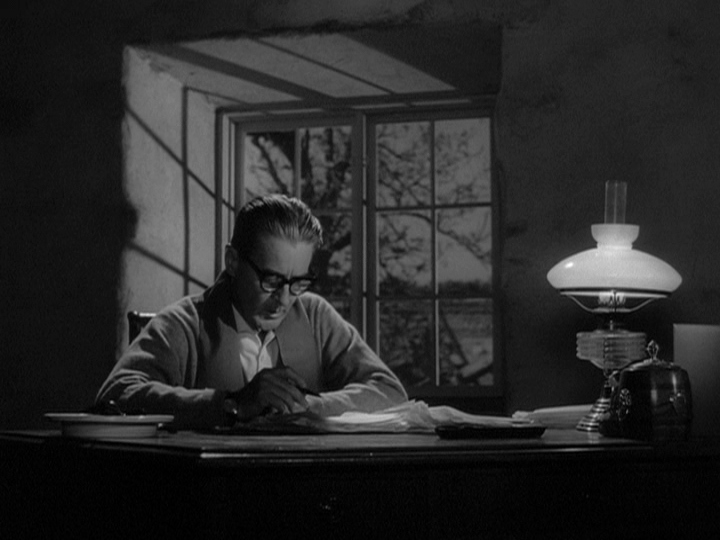

The severely narrowed aspect ratio contributes to this claustrophobia too, making for some particularly disorientating compositions of an upside-down Oliver reflected in ponds and dinner tables, and wide shots that close in Saltburn’s walls around us. Within these opulent interiors, Fennell draws a haunting beauty from the dim, golden lighting of lamps and candles, setting us up for jarring shocks each time she switches to a blood-red wash that encases its residents in mortal peril.

This danger does not simply emanate from Oliver though, as Fennell also prompts us to question whether the Cattons’ peculiar traditions and behaviour are truly as innocuous as they seem. From this angle, Saltburn appears to be in direct conversation with Jean Renoir’s class satire The Rules of the Game, underscoring the complete absurdity of the family’s black-tie dress code for dinner, and the strange request to remain cleanshaven so as not to incite Lady Elsbeth’s irrational fear of beards.

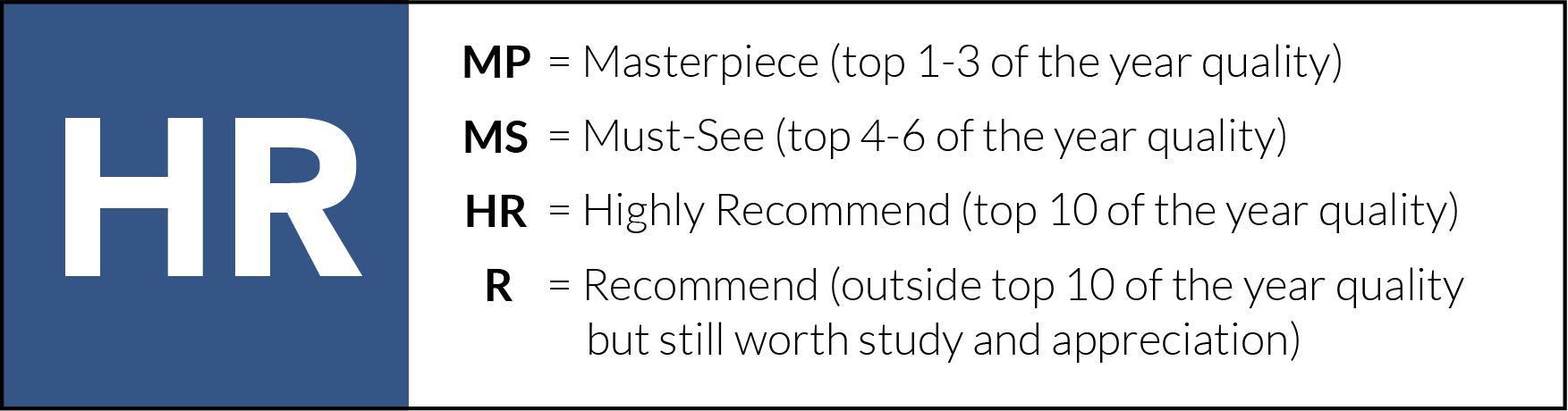

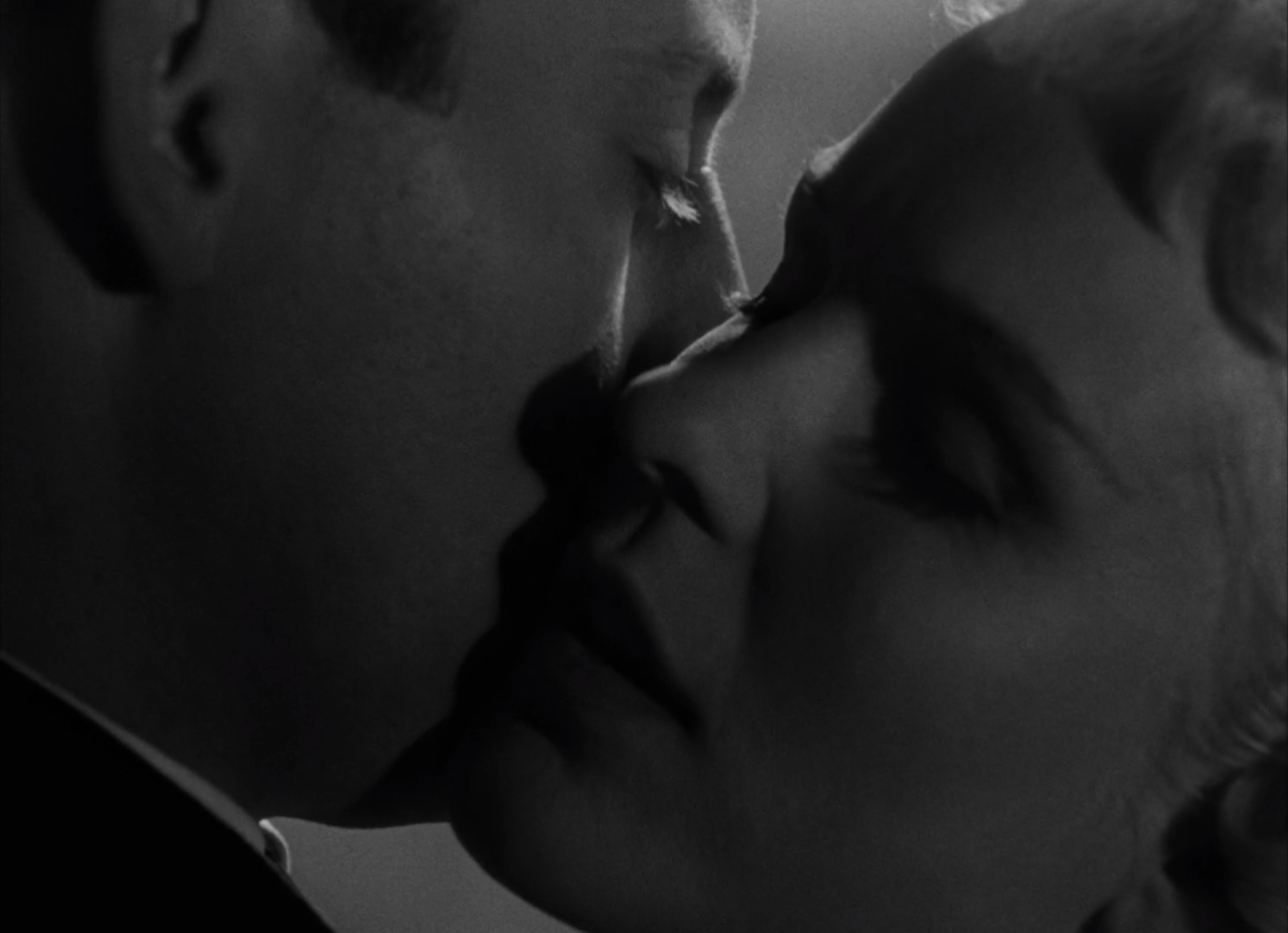

Rosamund Pike offers brilliant comic relief in this role, right next to Richard E. Grant’s maddeningly gleeful Sir James, though the greatest achievement here belongs to Barry Keoghan. Looking back at his collaborations with Yorgos Lanthimos and Martin McDonagh, it seems as if his career of playing unconventional misfits has built to this unrelenting portrait of obsession, perversion, and manipulation. Whether at Oxford or Saltburn, it is impossible for Oliver to blend into crowds, though he doesn’t exactly try hard either. His choice to wear a pair of stag antlers at his Midsummer Night’s Dream birthday party is subtly symbolic, asserting his primal masculinity in stark opposition to the men and women who dress in fairy costumes. When his outward meekness isn’t shrinking him in the frame, Keoghan confidently dominates Fennell’s compositions, most prominently while seducing his hosts. Venetia may be the one luring him out into the gardens late at night, but as he lines up his facial profile behind hers in a close-up and whispers commands into her ear, the link between his physical and psychological influence visually manifests onscreen with invasive intimacy.

If we are to believe his voiceover’s claims that such actions are genuine expressions of love, then we would be severely underestimating the depth of his inner emotional turmoil, and the extent to which it robs him of the control he desires. To make matters even more complicated, the Cattons still view him as a lowly child of the working class, and so he must make certain capitulations for the sake of his hosts’ egos and sensitivities. Felix and Venetia are happy to exploit his insecurity when they demand he strip to join them sunbathing, and later when he is tricked into performing a demeaning karaoke song, his resentment only continues to build.

Perhaps then Oliver’s love of Felix is not so much a romantic or sexual attraction, but a desire to inhabit his very being, and to access the privilege that comes with it. In this way, Saltburn’s intricate examination of power plays within a rigid social hierarchy bears many similarities to other contemporary class satires such as Parasite and The Favourite, though Fennell’s eccentric characters have nothing to hide but repulsive, hollow hearts. Some may mask it with lavish displays of charity, and others with a superficial subservience to their superiors, but as Saltburn reveals at the centre of its brilliant maze, this twisted game of exploitation will only be won by whoever is prepared to sink the lowest.

Saltburn is currently playing in cinemas.