Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 47min

Though often described as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage, Saraband is not so much an interrogation of that famous relationship which saw divorce rates rise across Sweden as it is an observation of the imprint it has left on those younger generations left to carry its legacy. There are a couple of fresh faces present here in Börje Ahlstedt and Julia Dufvenius, while for Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson this film marks the end of an era. Not only is it their final collaboration with Ingmar Bergman, but for the celebrated Swedish director it is also his last work before he passed away in 2007, and a notable return to form after many years of creating less-than-admirable television movies.

Saraband may not be the first time he has contemplated regrets of old age, though compared to the pensive meditations of Wild Strawberries and Autumn Sonata, this screenplay is far more grounded in Bergman’s firsthand experience of the matter. Save for a few minor dreams and flashbacks, these narrative diversions are excised altogether, and instead this story of reunited ex-lovers is delivered through a series of ten chapters not unlike the six parts of Scenes from a Marriage.

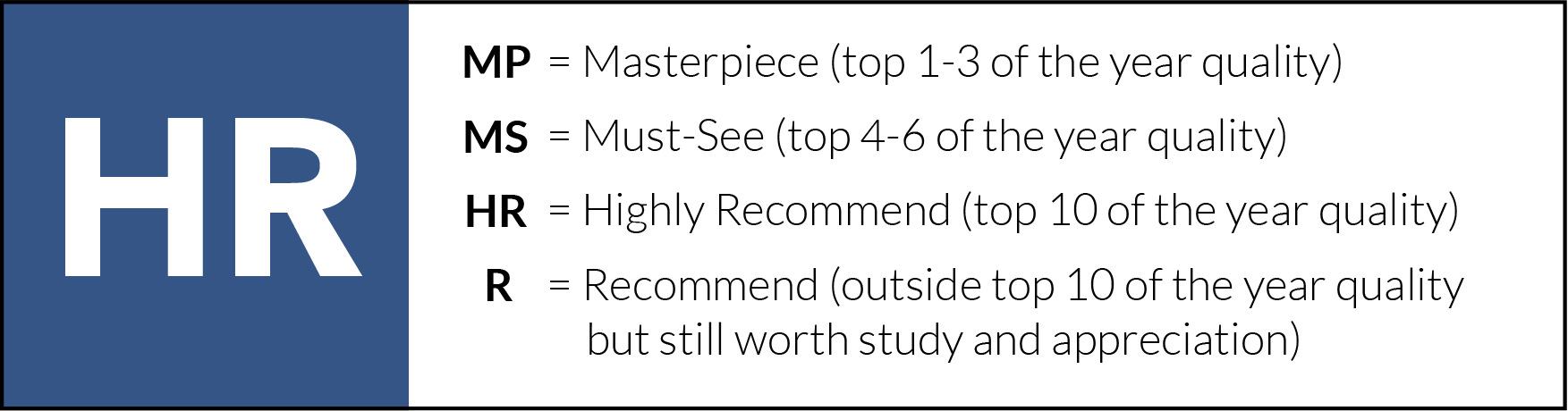

The result is a film that takes the form of a written memoir, framing an aged Marianne as our first-person narrator who pours over photographs of her life, and whose direct addresses to the camera bookend the narrative in a prologue and epilogue. Her absence from so many chapters is not an oversight on Bergman’s part. Each scene in this chamber drama is purposefully written as a two-hander, crafting rich dynamics from all the possible pairings between our four central characters – Marianne, Johan, his estranged son Henrik, and his freedom-seeking granddaughter Karin. Among them, Marianne appears to be the only one who is most content with herself, having put her psychological demons evident in Scenes from a Marriage to rest many years ago. She does not seek to become an active part of Johan’s family drama, but instead she carries a largely observational and counselling presence, offering warm wisdom to those willing to listen.

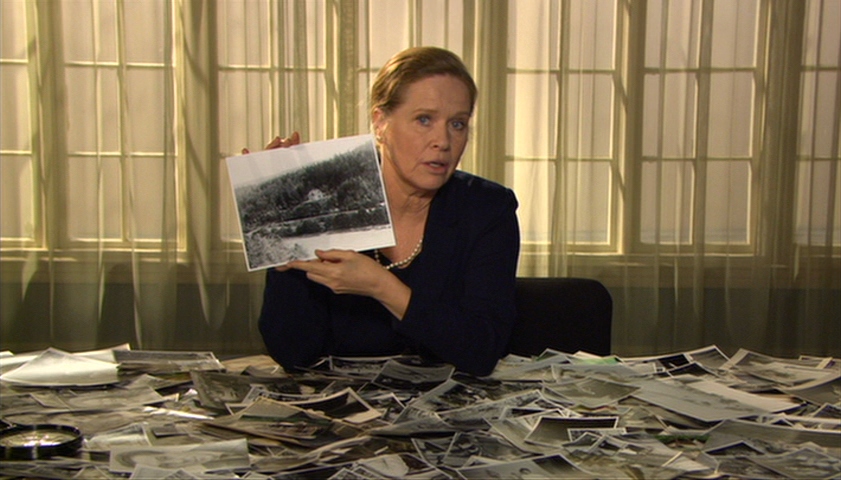

For an elderly Johan staring down the end of his life, Marianne’s impromptu visit couldn’t be timelier in helping him make peace with his own psychological troubles. It is somewhat surprising how little animosity there is between them, especially given how firmly he holds onto old grudges against Henrik which consequently left a broken family in their wake. In the absence of his alienated father and deceased wife Anna, Henrik has made the unsettling decision to attempt filling every role in his daughter’s life, thus not only positioning himself as her cello tutor, but also, quite disturbingly, as her lover.

The messiness of human entanglements has long been at the centre of Bergman’s writing, and sixty years after his early melodramas in the 1940s he is quite astonishingly still finding new angles on the jealousy and insecurity that hides within our most intimate relationships. Much like Johan and Marianne’s arguments in Scenes from a Marriage, Henrik’s seething expressions of acrid resentment reveal far more about his own spiteful soul than the target of his derision, taking perverted pleasure in the suffering he mentally projects on his father.

“I hate him in all possible dimensions of the word. I hate him so much, I would like to see him die from a horrible illness. I’d visit him every day, just to witness his torment.”

Ironically enough, it isn’t too hard to imagine Karin a few years down the track holding similar feelings towards the man who speaks these words. Bergman struggles to develop a strong visual aesthetic in Saraband, though the strained relationship between Henrik and Karin becomes abundantly clear in his trademark composition of their parallel faces lying horizontal in bed, as he desperately begs her to audition for a nearby music conservatory so she can stay close by his side.

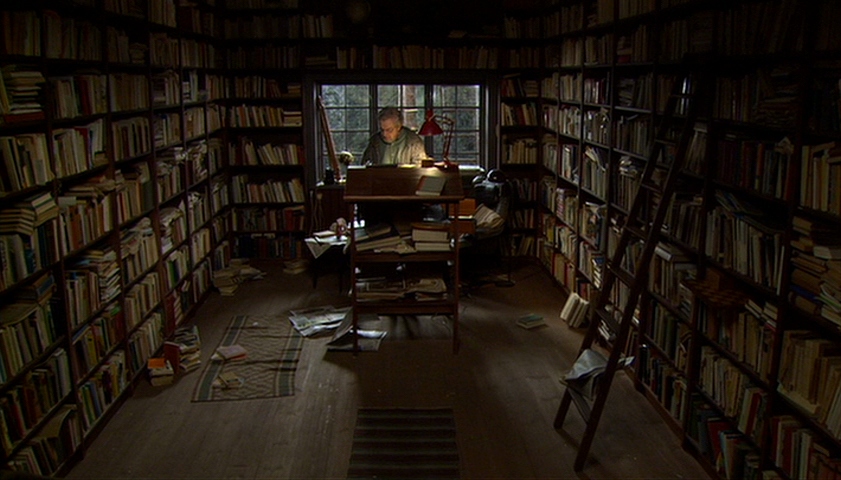

It isn’t until after speaking with Johan and Marianne individually that Karin finds the courage to set out on a new path, following her friend to Hamburg to perform in an orchestra, and thereby rebelling against her father’s isolative preference for her to pursue a career as a solo cellist. There is a beautiful synchronicity between this arc and the accompanying music too, ringing out the lonely lament of a single cello throughout much of the film, before growing into a full orchestral symphony as Karin envisions a future of her own choosing. Bergman is not a director who typically makes extensive use of film scores, though certainly his love of classical music has persisted through his work ever since 1950’s To Joy, elegantly expressing his characters’ deepest yearnings.

Perhaps the most profound of all these longings though is for a figure who is almost completely absent in Saraband, represented only in the framed photographs that adorn Johan, Henrik, Karin, and even Marianne’s personal spaces. The grace that Anna brought to their lives is sorely missed, and it is only thanks to her that Karin ever really knew what it meant to feel the kind, unselfish love of a parent. Through Anna, Henrik was made fully aware of his failings as a father, and perhaps he might have even been able to fix them had she not passed away. As it is though, all she was able to leave him was a letter written shortly before her death, professing her love yet warning him against further wounding his relationship with Karin.

Unlike virtually everyone else in this ensemble though, Henrik cannot simply let go of those who are ready to move on without him. His failed suicide attempt after Karin’s departure for Berlin is the bleak conclusion to his story, though Bergman decides to sit a little longer with those two characters whose richness and authenticity secured his place in popular culture thirty years prior. As an anxious Johan finds comfort in Marianne’s arms after a night of restless sleep, the two bear their naked bodies to each other for the first time in decades, finding an intimate, humbling honesty that cuts through the existential terror of old age. In the last moments of Bergman’s last film, there are no vicious verbal attacks or extreme acts of spiritual desecration to be found. Much like Marianne, Bergman too finds peace in the act of introspective reminiscence, allowing him to finally appreciate the pure bond between lovers, parents, and children that transcends all other worldly distractions.

Saraband is currently available on DVD from Amazon.

One thought on “Saraband (2003)”