Vsevolod Pudovkin | 1hr 27min

The defiance of a lone, unarmed rebel standing against a tyrannical state is unlikely to shift the course of history. Their position is hopeless, dooming them to perish beneath the boot of their oppressors as so many others have before them. It is not this singular protest though which elevates them as a countercultural icon in Mother, but rather the tragedies that have led them to this point, radicalising those who find strength in defeat. While Sergei Eisenstein was celebrating the powerful solidarity of a unified working class in Strike and Battleship Potemkin, Vsevolod Pudovkin was turning his camera towards those whose resilience is fed by anguish, painting such individuals as models of Russia’s impassioned, revolutionary spirit.

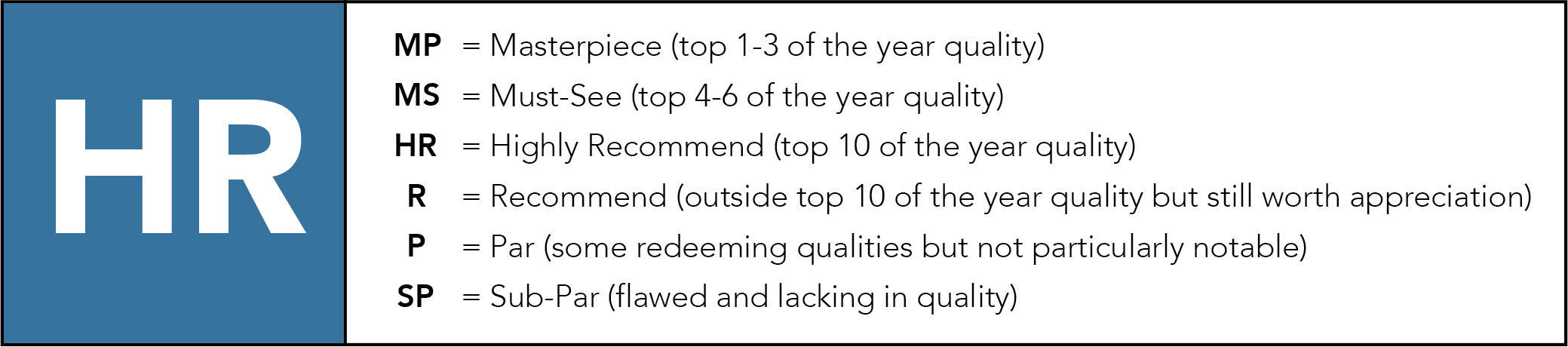

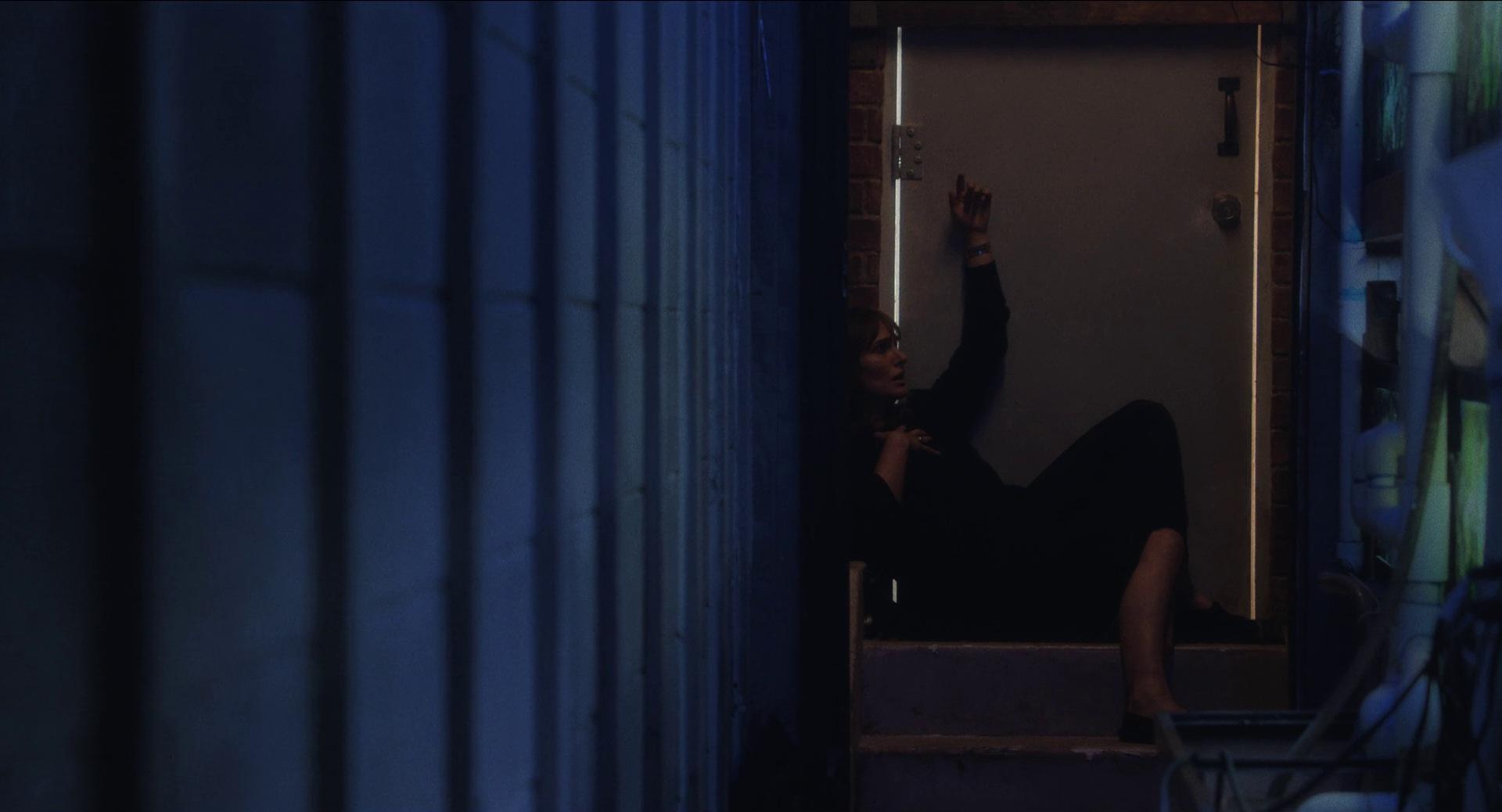

Pelageya is the long-suffering mother in question here, caring deeply for her adult son Pavel who in turn protects her from the abuse of her alcoholic husband, Vlasov. No one in this family holds any explicit political affiliations, though as subjects of pre-Revolutionary Russia, tensions run rampant in their local community. While Pavel is secretly helping local socialists by hiding a stash of handguns in his home, ultra-nationalist group the Black Hundred are bribing Vlasov to join their counterattack upon an upcoming workers’ strike, making for an awkward, unexpected confrontation between father and son when they come face to face at the protest. “So you’re one of them?” Vlasov furiously growls as he chases Pavel into a pub, only for his rampage to be halted by a stray bullet from a revolutionary’s gun.

As his killer is forcefully apprehended, Pudovkin takes a moment to cut away from the action. Rustling tree branches, drifting clouds, and gentle streams carry us out of the chaos, before returning to the broken body of the man who took Vlasov’s life, now lying dead on the floor. The strike is over, and the Tsarists have won, leaving a captive Pavel in the hands of a judicial system he knows is not on his side.

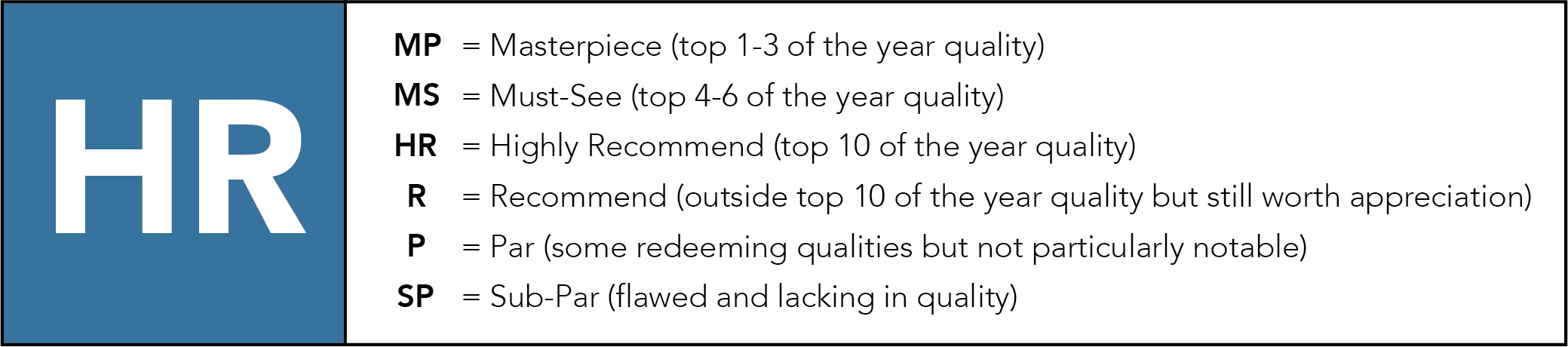

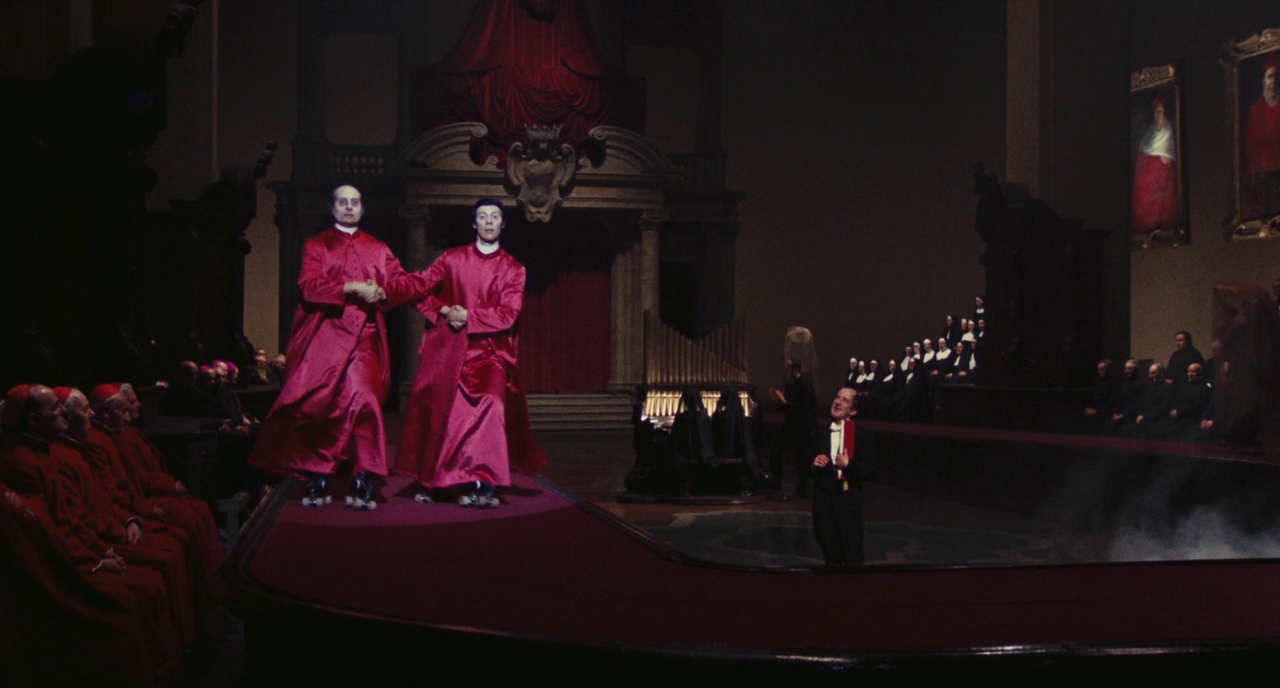

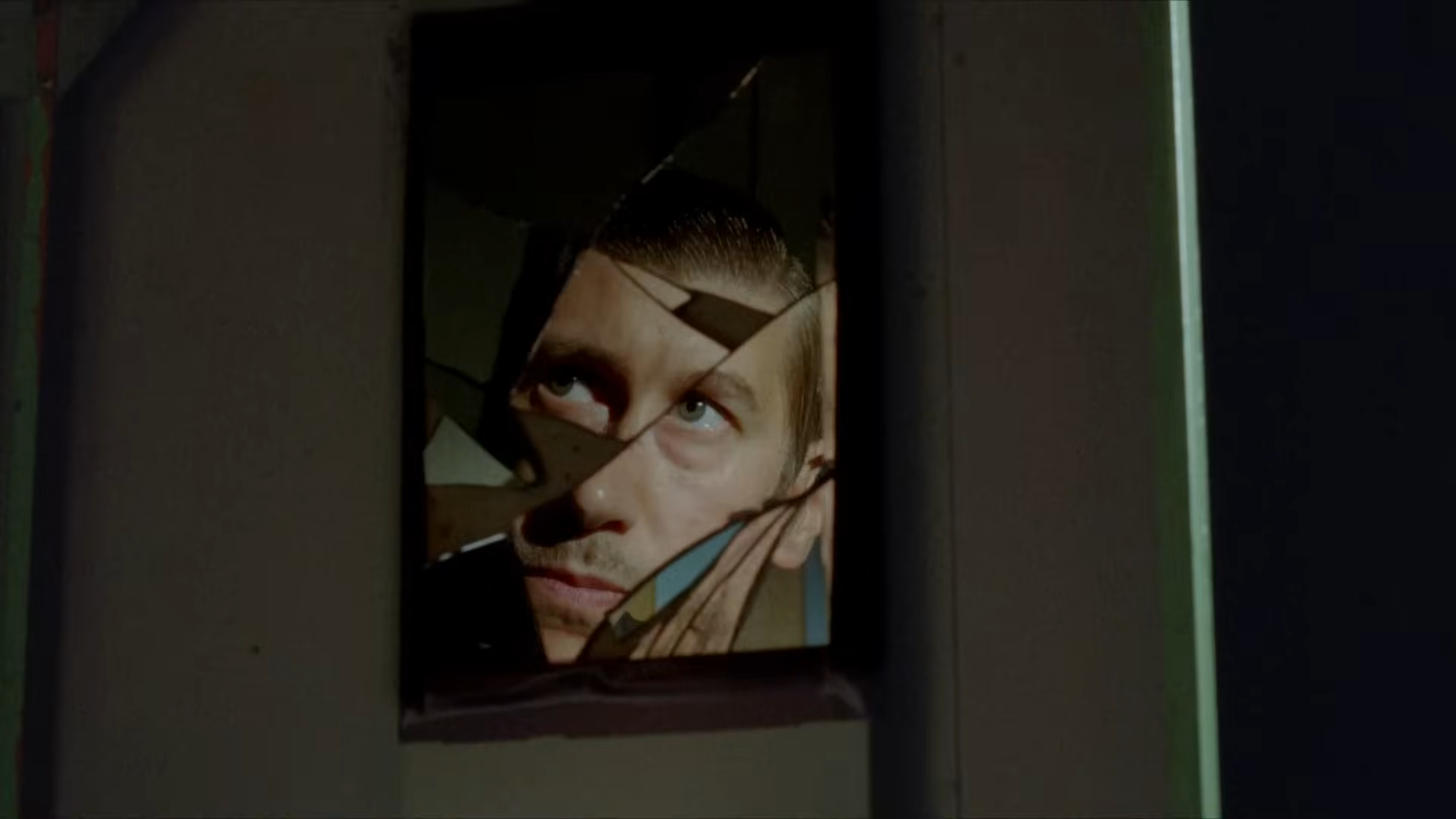

Through Pelageya’s mixture of grief and desperation though, she remains convinced that mercy will be granted if he confesses the truth. At Vlasov’s funeral, her mind wanders to that loose floorboard back at home, which Pudovkin rapidly dissolves to reveal the stash of firearms below. Later at Pavel’s interrogation, her eyes shift nervously in close-up, intently observing the suspicious police officer, her son’s stoic denial, and his clenched fists behind his back. Her torment is unbearable, and finally reaches a breaking point when she reveals the hidden firearms – only to worsen again when she recognises the dire, irreversible consequences of her actions.

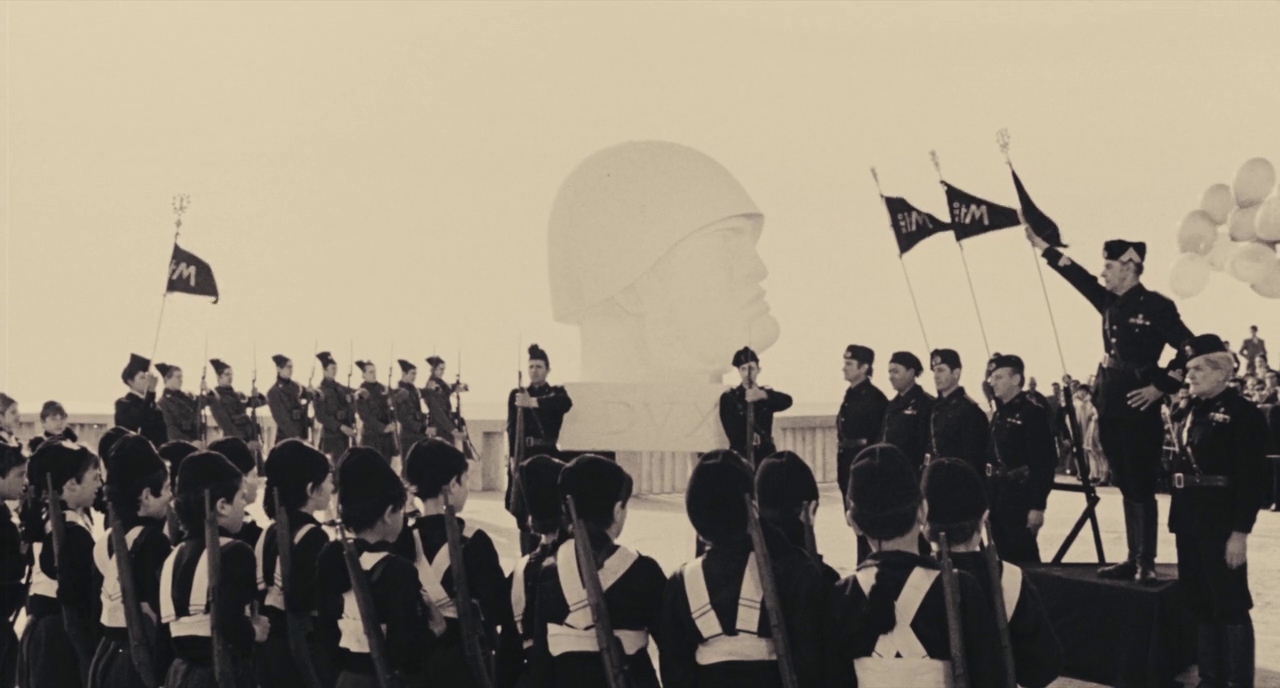

Given that Mother‘s intimate drama operates on a relatively small scale, the editing isn’t quite as spectacularly complex as Eisenstein’s, though Pudovkin’s development of narrative continuity through montage is nevertheless a remarkable achievement. Where Eisenstein produces meaning from the abstract collision of images, Pudovkin emphasises the seamless flow of emotions, placing more weight on each individual shot. Especially when it comes to the juxtaposition of close-ups during Pavel’s trial, his editing delivers an intense clash of expressions, preceding The Passion of Joan of Arc’s historic innovation of this technique by two years. There in the Russian court of law, the judges’ sheer incompetence, laziness, and prejudice are on full display, and Pudovkin doesn’t miss the chance to implicate the highest levels of government through cutaways to a bust of Nicholas II.

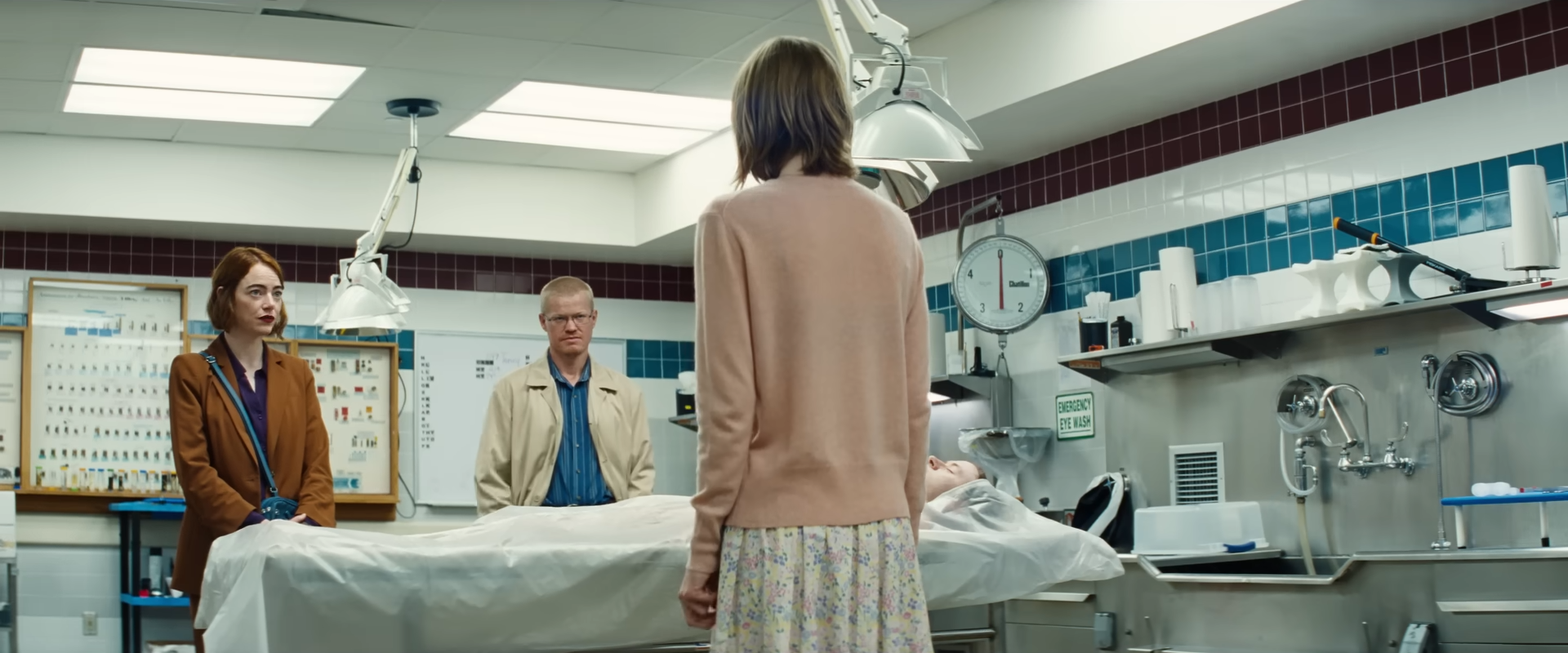

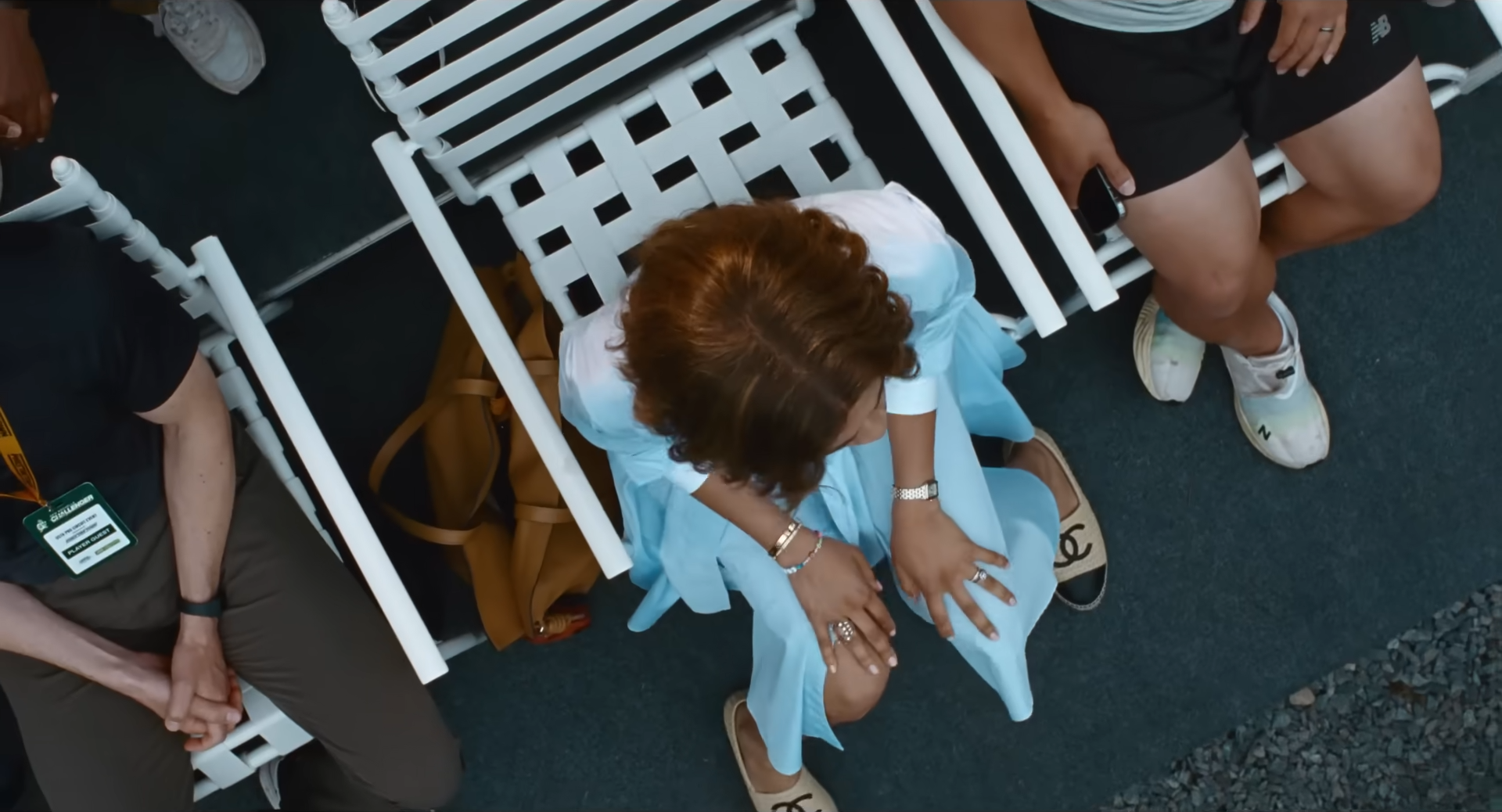

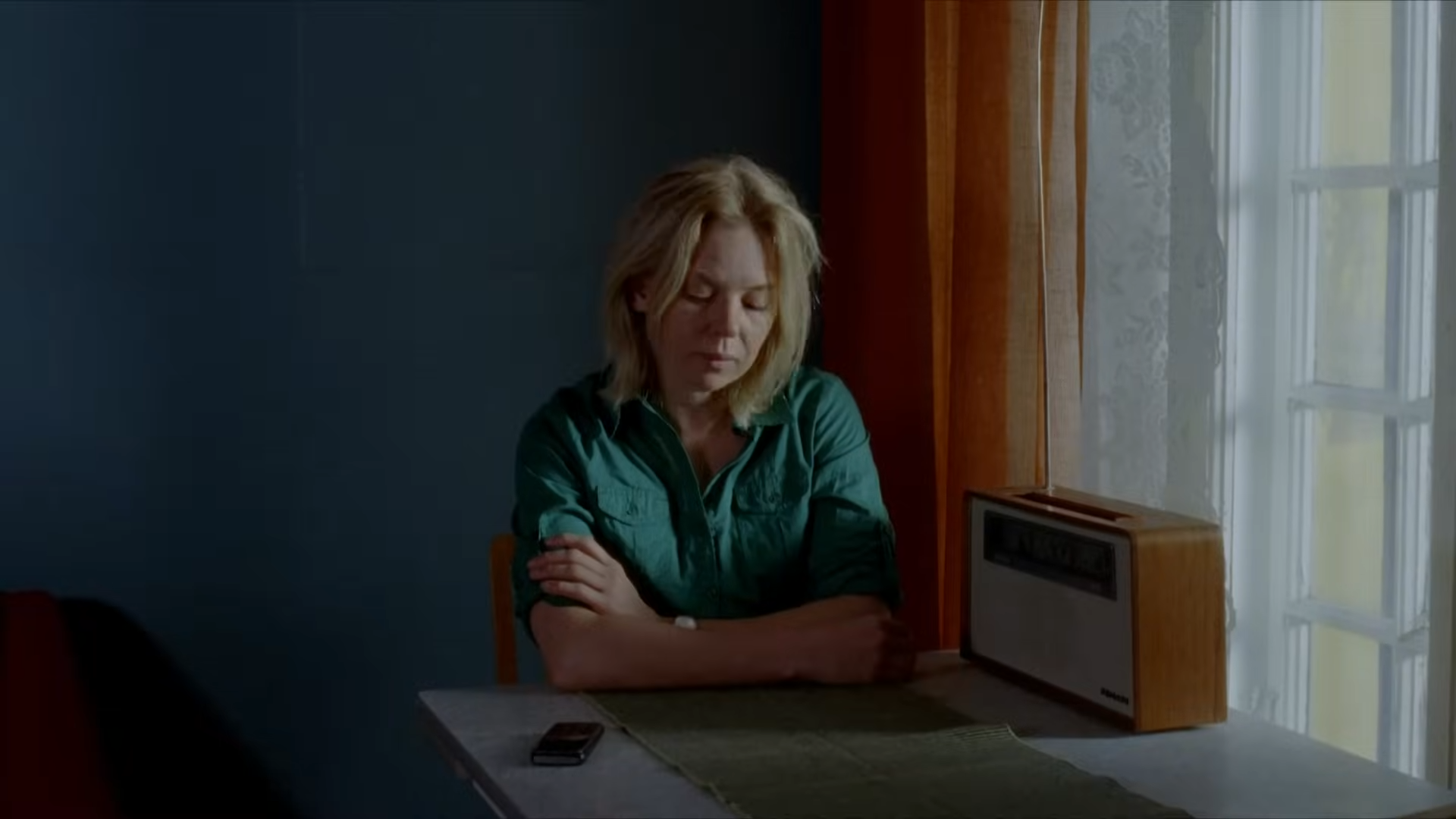

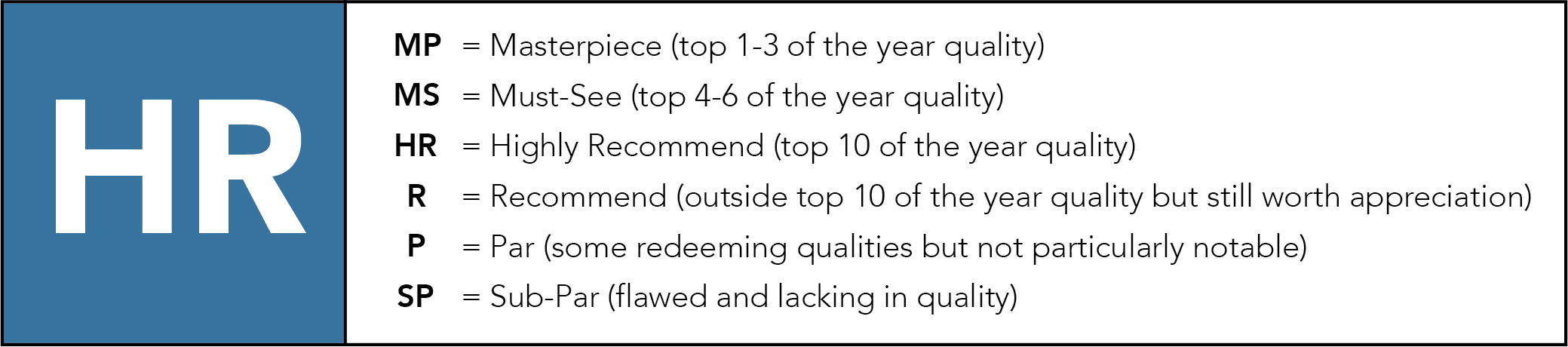

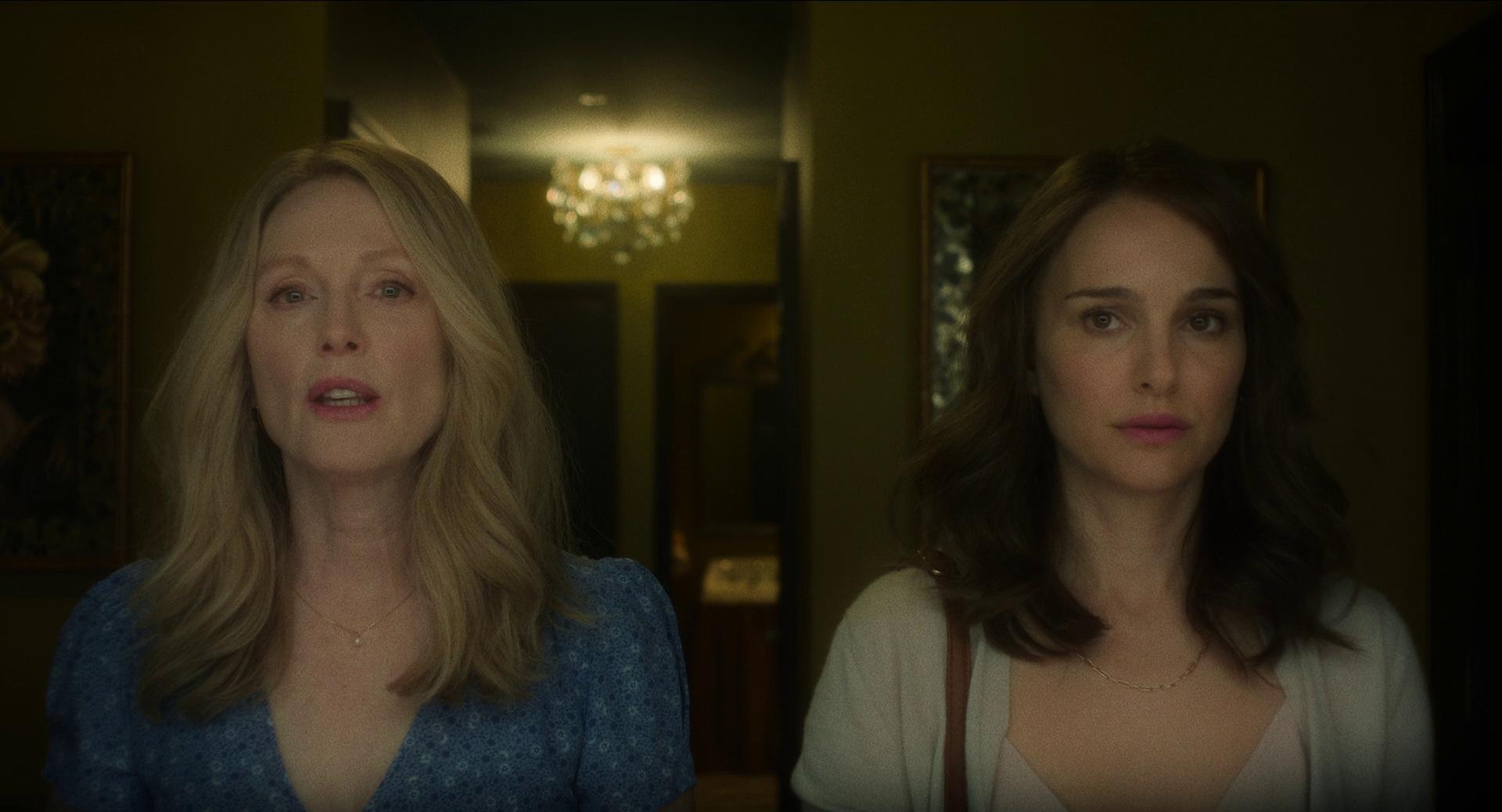

As Pelageya’s lonely head pokes above empty rows of courtroom seats though, Pudovkin reminds us where the emotional centre of this film lies. Gradually over the course of Mother, actress Vera Baranovskaya visibly unravels, her tired eyes drooping and her posture slouching with dwindling hope. Only when her son’s sentence to a life of hard labour in Siberia is delivered does she abruptly rise from her seat, stretching her face wide with horror as she indignantly screams – “Where is truth?!”.

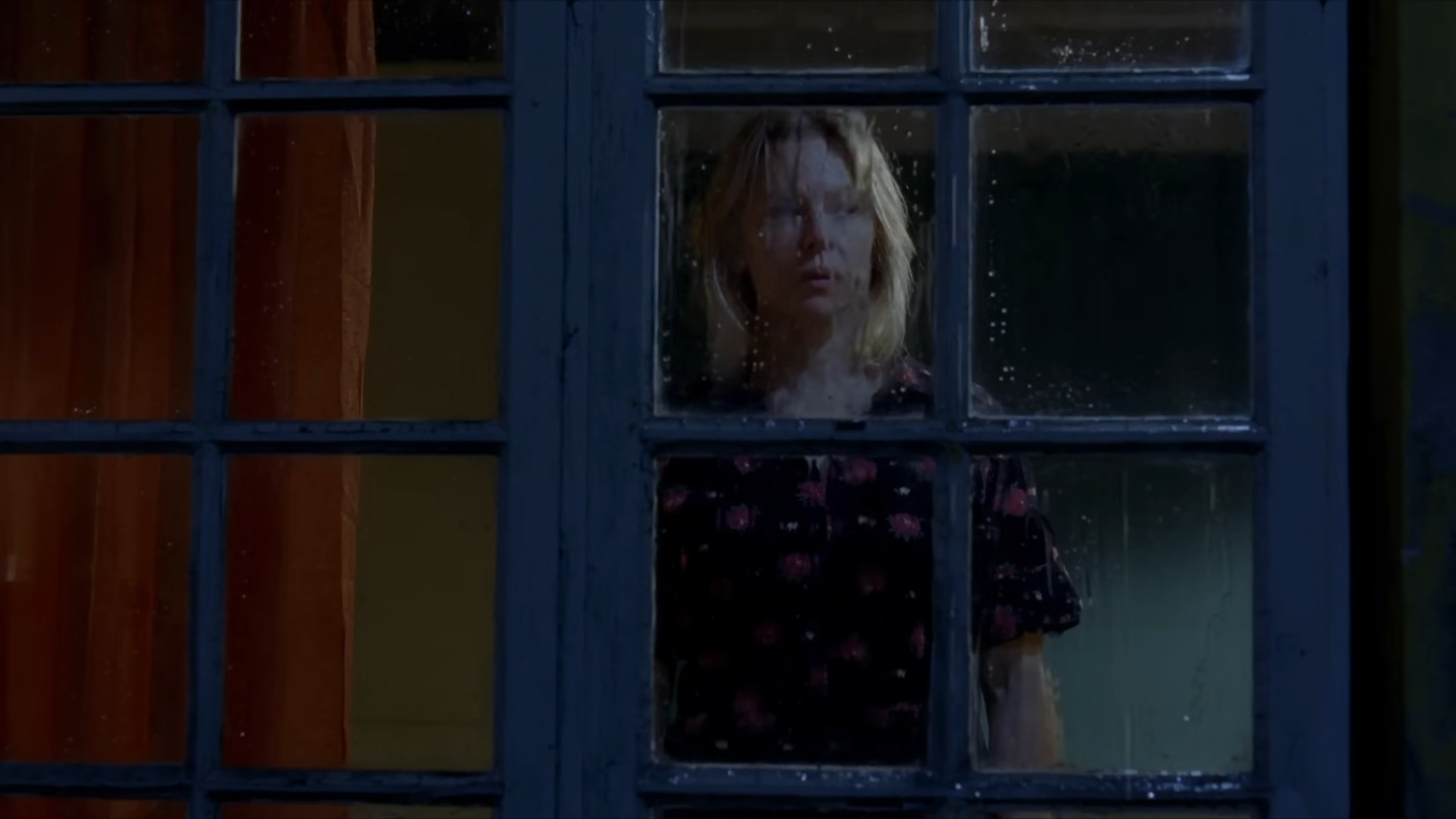

For the first time, Pelageya’s agony does not wane into dreary depression, but rather explodes with fury. Once out in the world, that righteous anger is not so easy to put back in its box either. Even when it eventually simmers down, still it manifests as seething resentment, following her all the way to Pavel’s prison some months later.

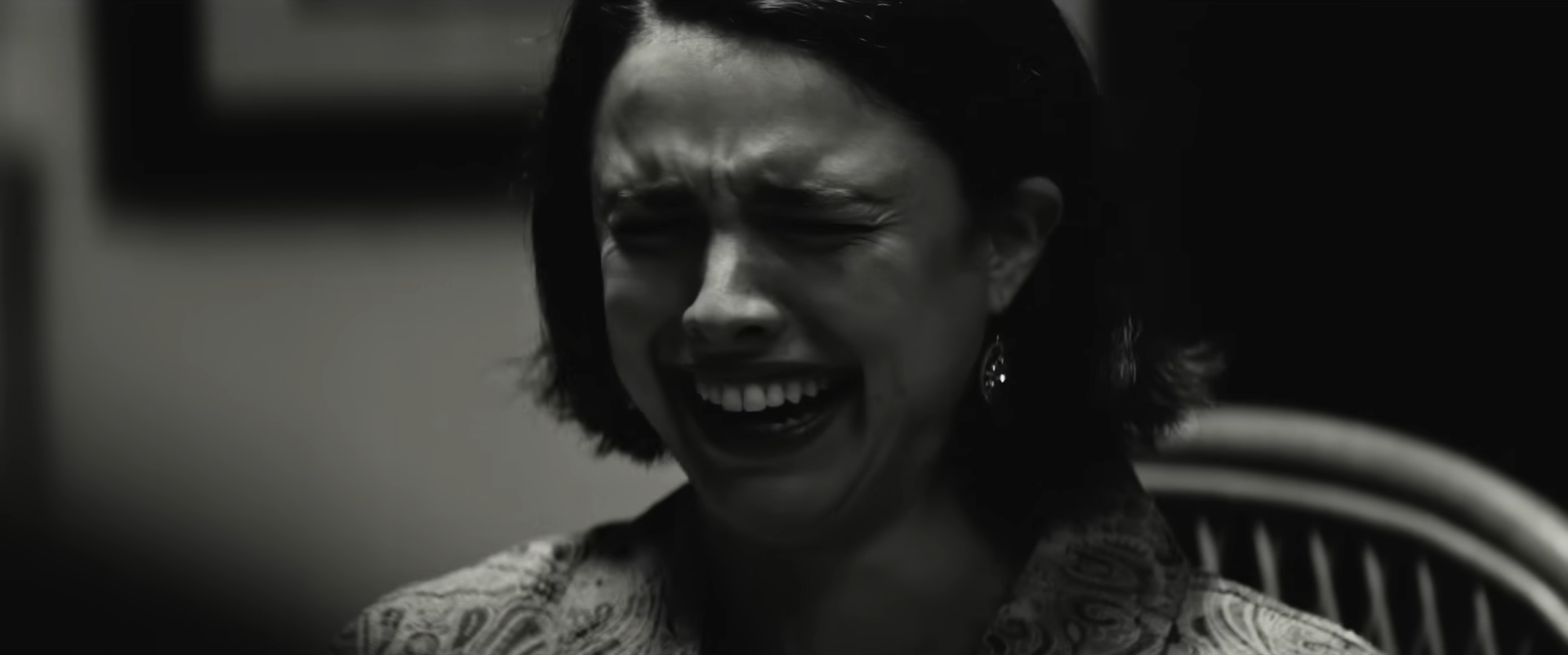

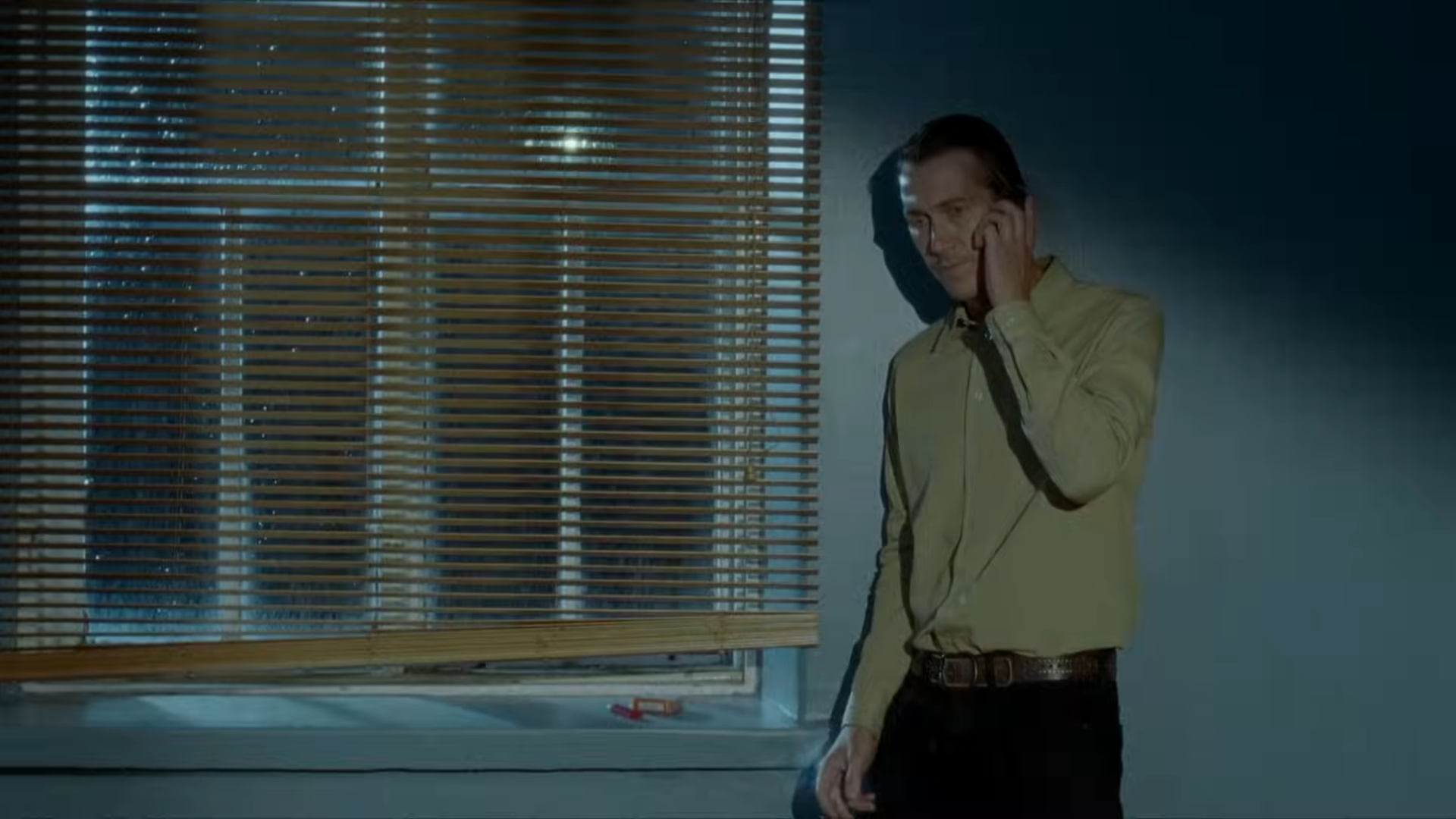

With this narrative transition, Pudovkin once again delivers more montages celebrating the natural world, contrasting the inmates’ dreams of sunny, open pastures back home to the melting ice floes of Siberian rivers just outside their cells. Spring has arrived in this frozen wasteland, and nervous excitement is in the air. Between the latest batch of visitors making their way to the labour camp with a socialist flag and whispers of a prison break, Pudovkin’s parallel editing generates palpable anticipation, drawing the reunion between mother and son ever closer.

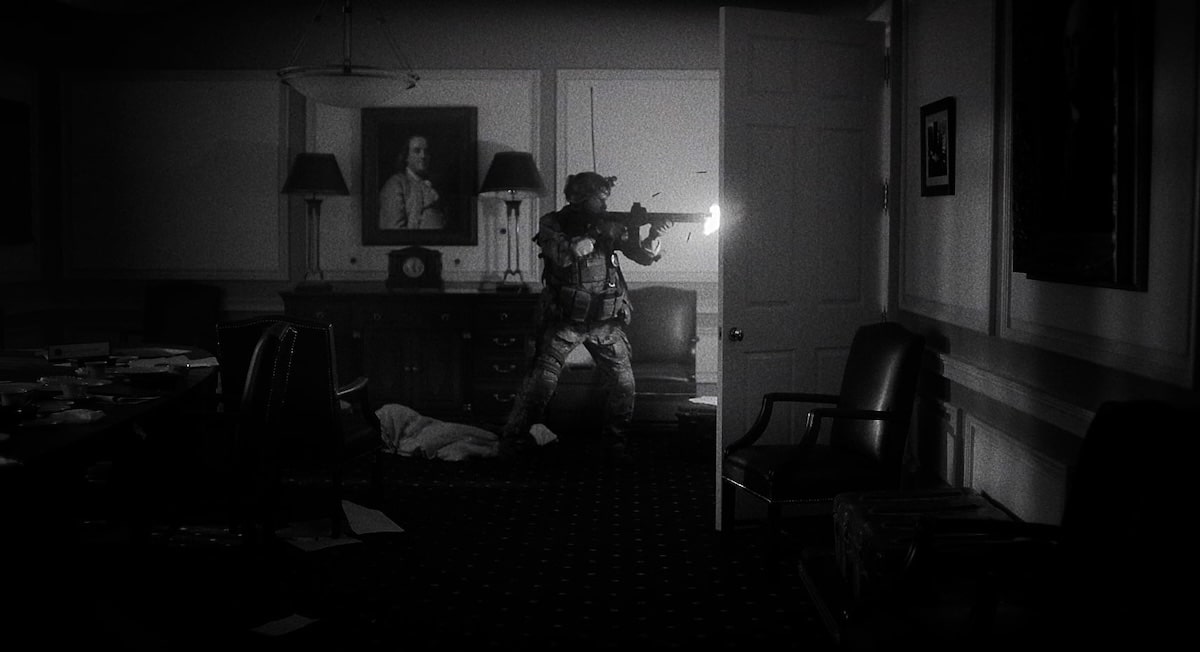

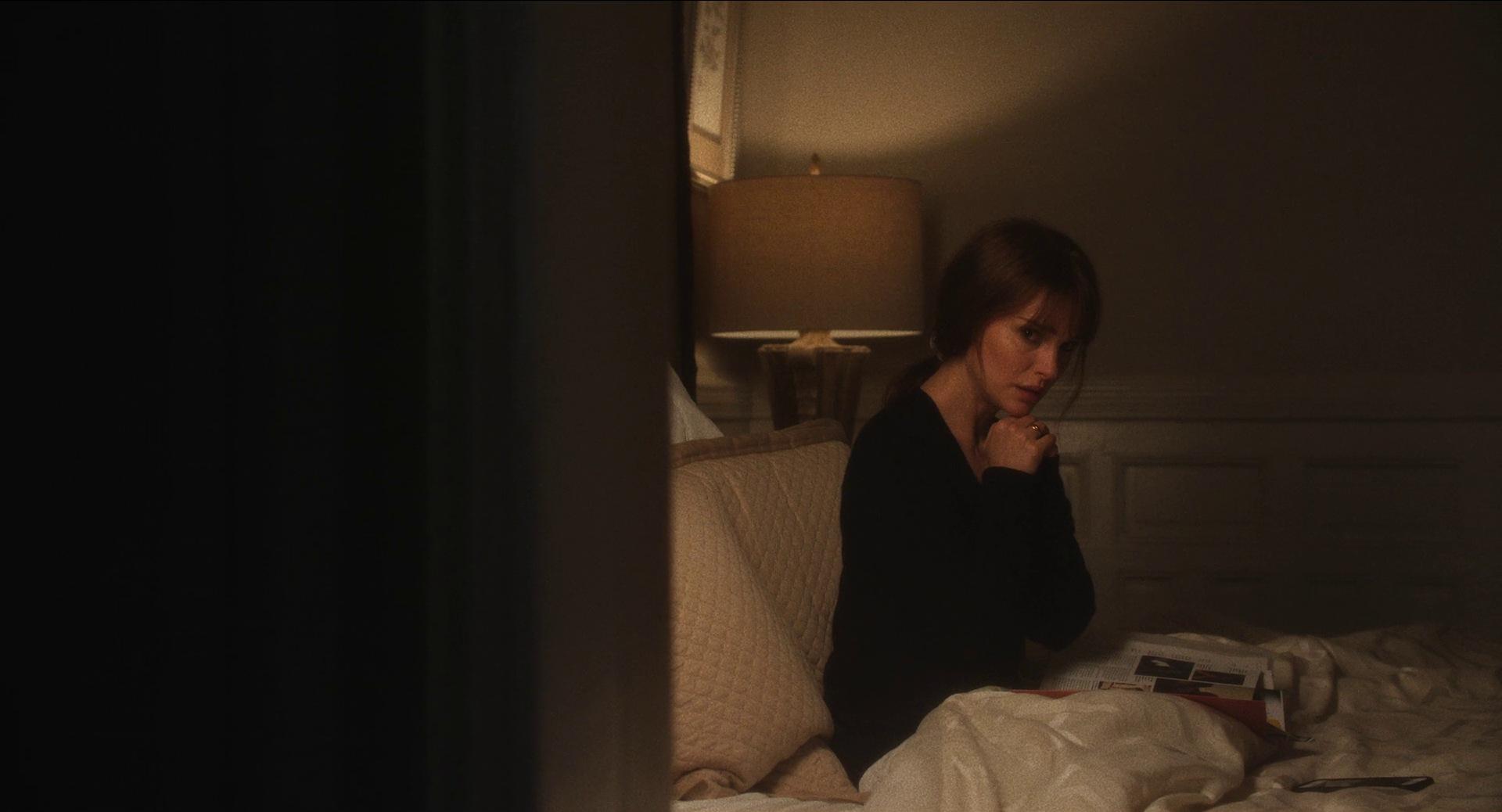

From here, the violent action which unfolds is a tightly choreographed dance between hope and despair, carrying this daring set piece aloft upon swift, unyielding momentum. The collective effort of the inmates ramming down doors, climbing walls, and overwhelming guards is largely successful, though Pavel soon finds himself cornered when faced with that vast, glacial river. Still, the only path is forward, and thus he begins jumping from sheet to sheet in epic long shots intercut with daunting close-ups of breaking ice.

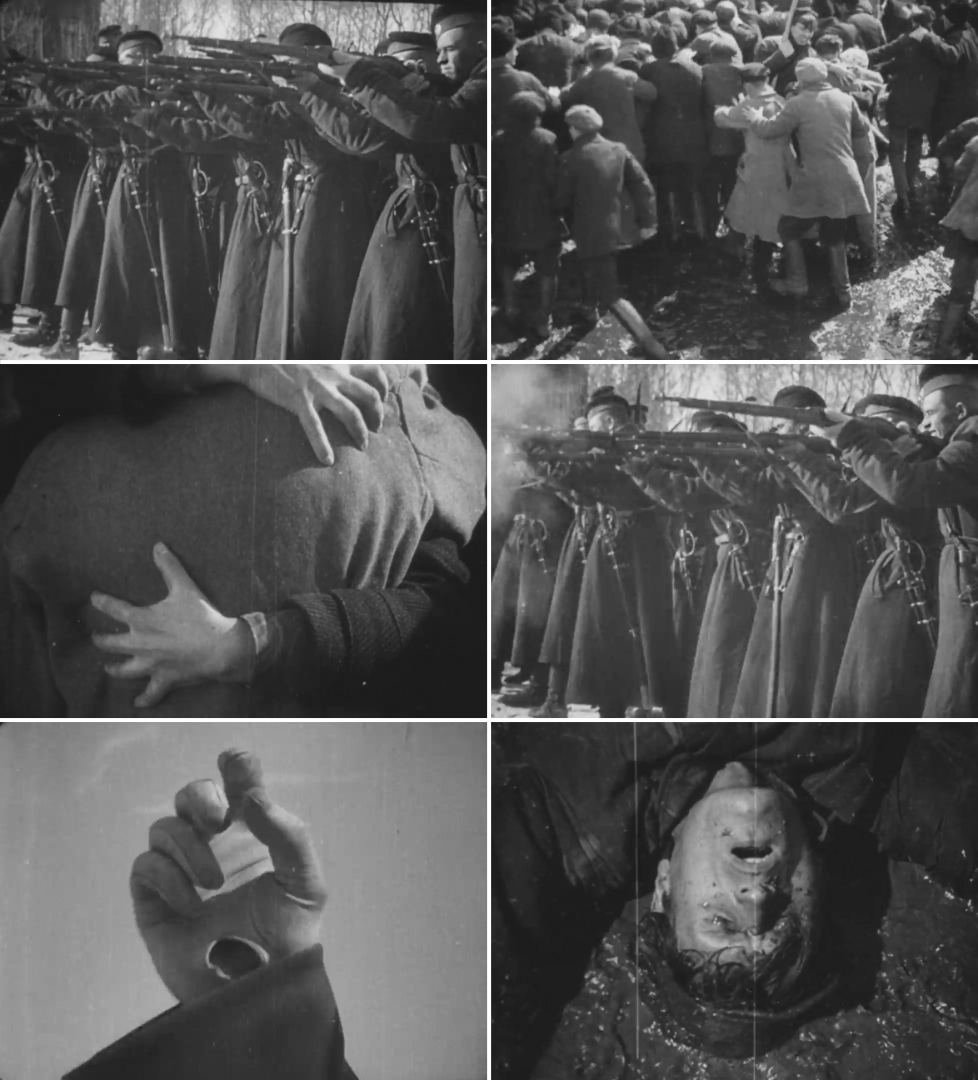

From the other side, the visiting protestors are keen to celebrate the escapee, though none are so ecstatic as his mother. Her arms wrap him in an embrace so tight that only death itself could tear them apart – and that is exactly what the cavalry tragically delivers as they ride across a large, steel bridge, firing bullets at the crowd. Kneeling over her son’s body, she weeps, and becomes the only remaining visitor to not instantly flee at the first shots.

In this moment, Pelageya transforms. The very foundations of her motherhood have been stripped away, and yet her maternal instincts persist, inspiring her to channel that fierce protectiveness she once reserved for Pavel towards the people of Russia. Within the fast-moving chaos, we carefully linger on her picking up the socialist flag, raising it to the sky, and fearlessly facing down the oncoming stampede in an imposing low angle. At last, the radicalisation is complete. Even as she is ruthlessly cut down like a martyr in these glorious final seconds, Pudovkin recognises that not even a hundred Tsarist troops can destroy her radiant spirit, infectiously shared among those lucky enough to witness the valour of a selfless, devoted mother.

Mother is not currently streaming in Australia.