Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 40min

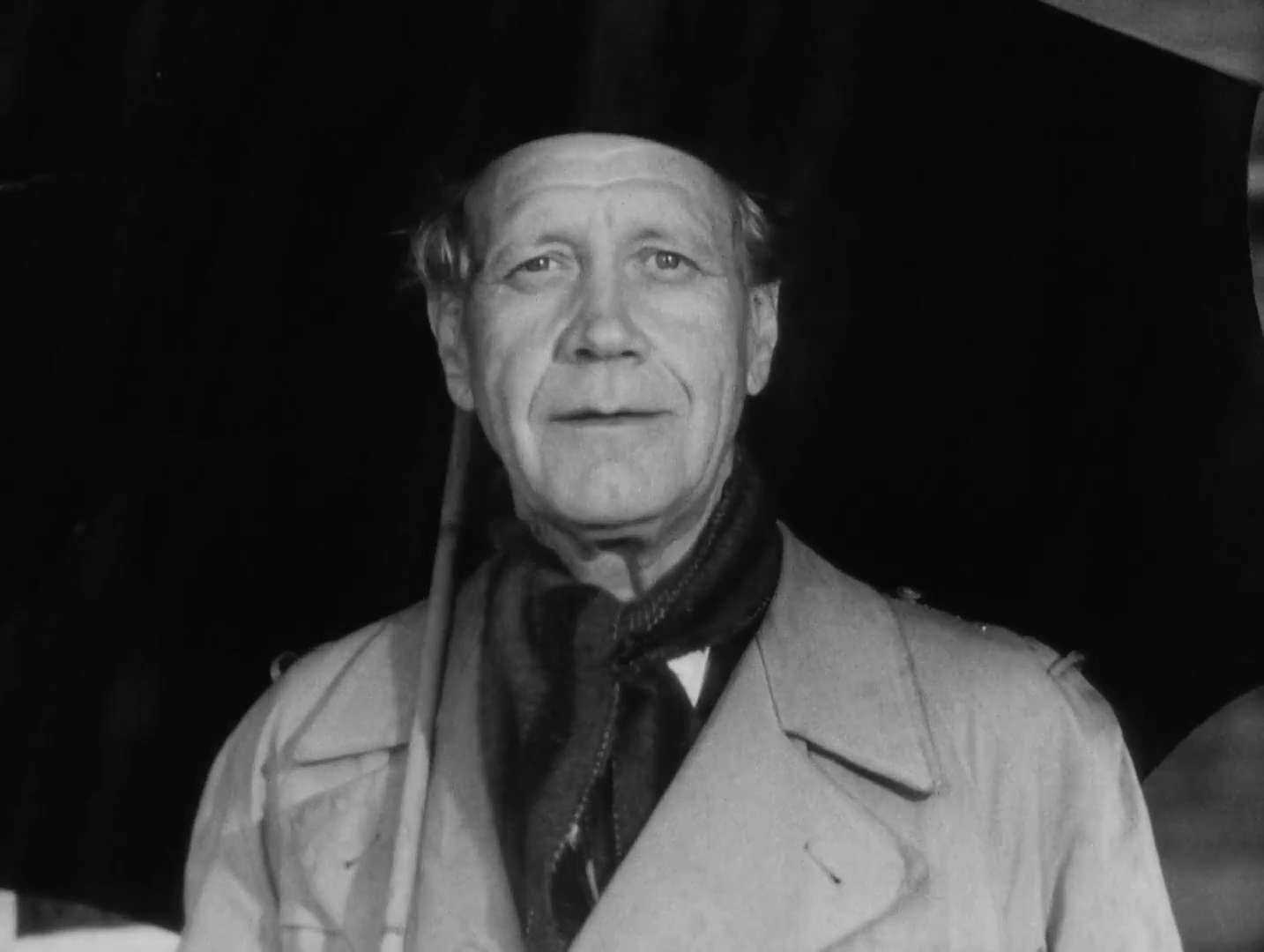

By the time Ingmar Bergman came around to directing his fifth feature film in 1948, Italy’s neorealist movement was in full, depressing swing, taking cameras to the streets of cities to capture the real struggles of ordinary people. Much like his previous works, romantic melodrama is the basis of Port of Call’s main storyline, and yet there is also an authentic grit here inspired by the Italians, wrestling with harsher realities of child abuse, abortion, and failed welfare services. In choosing to shoot on authentic docks and harbours, Bergman establishes his setting as a working-class port town, imbuing Berit’s troubles with a more nuanced sorrow connected to her helpless, abject poverty. As she stands on the edge of the water in the opening scene, ships, ropes, and steel beams form a harsh, industrial backdrop to her attempted suicide, offering little salvation in its cold visage besides the one kind sailor who dives in after her.

This first interaction between the two future lovers comes just at the right time for both. Where Berit was ready to give up on life, Gösta has recently returned from a long voyage and decided to settle down on the docks. A second chance encounter in a crowded dance hall pushes them even closer together, though building new relationships is not so easy when old ones continue to be the foundation of lingering trauma.

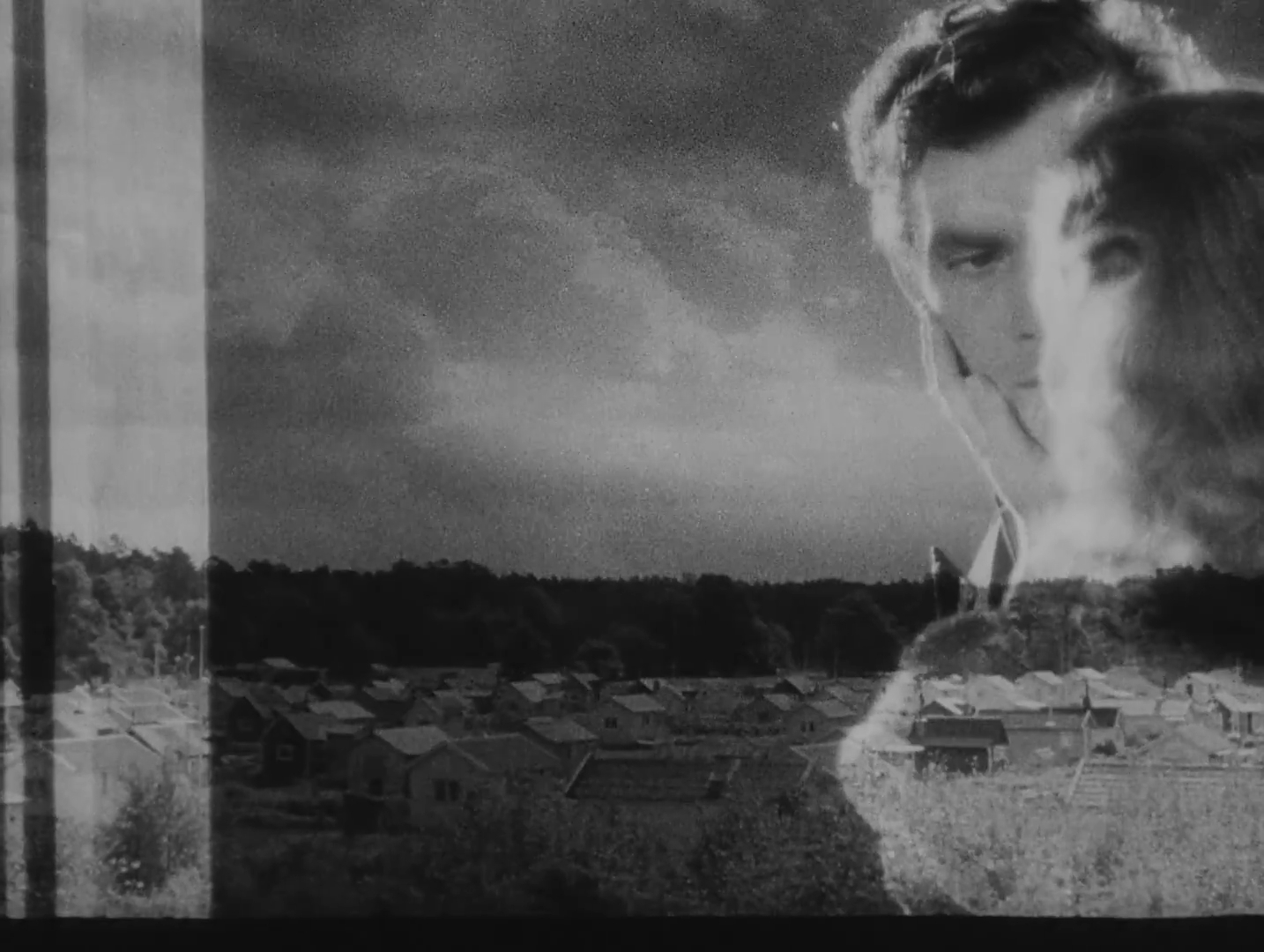

Flashbacks to those defining points of Berit’s childhood and adolescence are smoothly integrated throughout Port of Call, and are first brought in with a smooth match cut of her face dissolving into her younger self, lying awake in bed as her parents quarrel in the background. To them, she is simply a prop to be pulled back and forth in arguments with no regard for her perspective, and when she becomes a teenager, she is cruelly locked out of her own home for missing curfew. As a result, “I love you” is now an impossible phrase for her to speak, let alone understand.

“I hate those words. Everyone says them without meaning them.”

Bergman’s empathy towards his characters has been evident ever since his debut film, though the creative framing of close-ups which he employs here and would later turn into his visual trademark in the 1950s lands that sensitive compassion with even greater power and grace. Here, he often comes at the faces of his actors from oblique angles, tilting them away from the camera to catch their outline and nestling them against each other in bed, thereby crafting a beautiful intimacy between characters. Conversely, we often find him rupturing that tenderness with a terrible loneliness, using a splendid depth of field to reveal a disconnection amongst the girls in Berit’s reformation school, isolating her even further from an uncaring society.

Even beyond her past, there is a surprising cruelty in Gösta as well, who coldly spurns her upon learning of her previous relationships with other men. Like all of those, this does not seem to be a romance that will last, making the falsely optimistic note it ends feel particularly unearned. It is but an off note in an otherwise accomplished film for Bergman though, who at this point in his career is observing and learning from his fellow contemporary filmmakers. As well as the neorealist influence that sees him bring backgrounds to life with the action of moving cranes, the occasional montage of ships and docks between scenes feels slightly reminiscent of Yasujiro Ozu’s characteristic pillow shots, building a rhythm in transitions that offer a soothing quietude. Sailors and labourers may fill this port with bustling activity, yet the isolation of Bergman’s characters frequently overrides that liveliness, setting in a bleak tone that sees old traumas surface and threaten the chance for new beginnings.

Port of Call is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.