The Dardenne Brothers | 1hr 34min

The story of Igor’s relationship with his father, Roger, in La Promesse can be understood through the three-act journey of his signet ring. He first receives it as a stolen gift, and proudly compares it to the matching one Roger wears on his own hand. When he is forced to do his father’s dirty work, it gets grimy. Afterwards, Roger is right there to polish its surface, erasing all traces of what went down. In this unjust world it is his most treasured possession, both for its sentimental and monetary value, so his final, selfless decision to pawn it off for the benefit of someone else in need marks a major shift in his loyalty. The Dardenne Brothers are dedicated realists on every level of their filmmaking, tying their narratives up into knotty moral predicaments, and yet it is through these tinier symbolic developments that La Promesse progresses with archetypal formality, leading Igor down the path to maturity and the responsibilities that come with it.

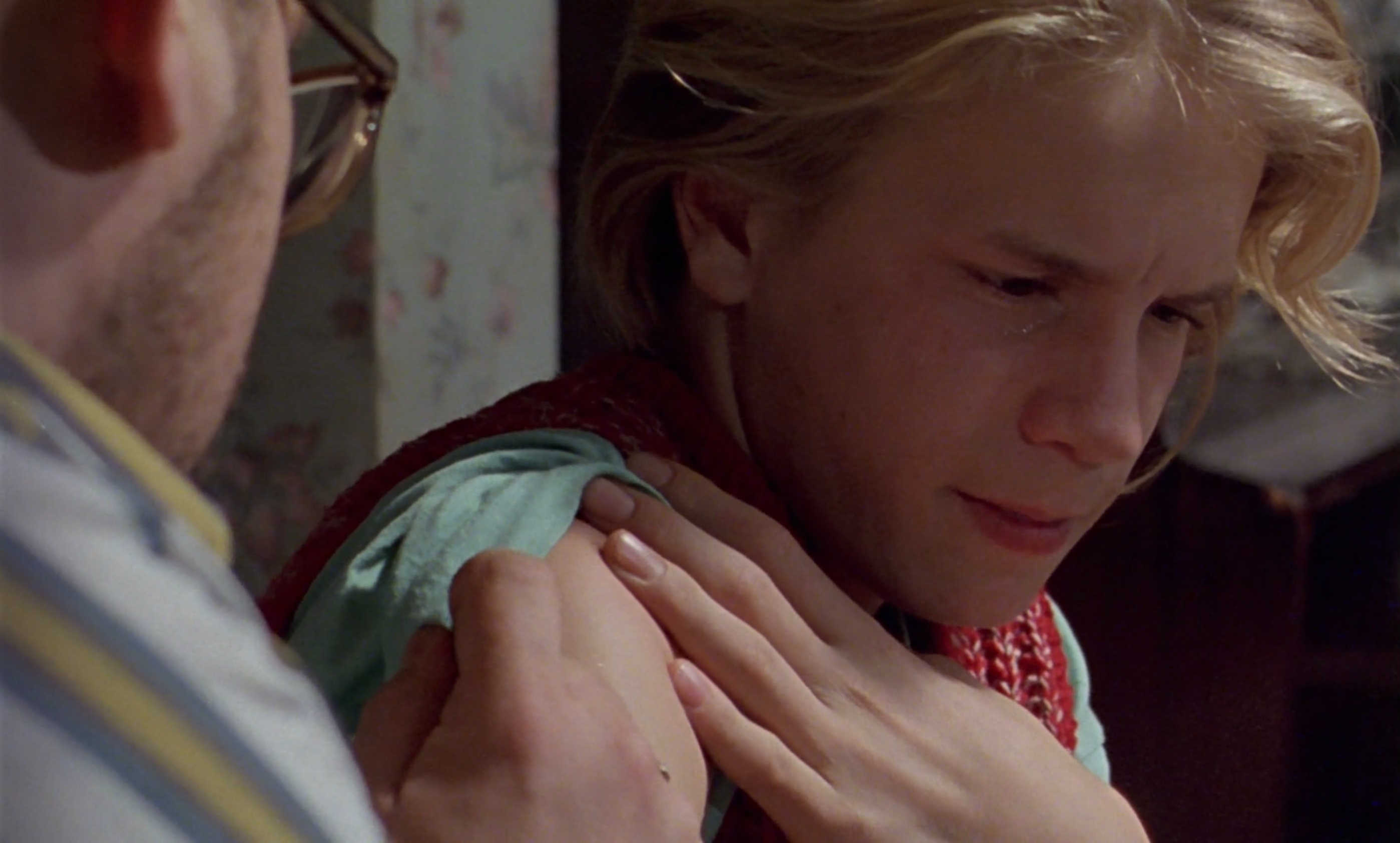

In 1996, this film marked a cinematic breakthrough for the Dardennes, who carry the neorealist traditions of 1940s Italy into contemporary Belgium and its own unique set of social issues. Exploitation of undocumented immigrants, trafficking, gambling, and petty theft thrive in this small industrial town, swaying the prospects of its local youth away from respectable occupations and towards the corruption of their elders. Right in the opening minutes, Igor steals a purse from a woman without a whole lot of guilt, clearly following in his father’s steps as an amoral, opportunistic criminal looking to take advantage of the system. Being a teenager though, his childhood innocence has not yet entirely faded. He would much rather ride bikes and go-karts than pursue his dead-end future, and in the formal repetition of these shots hanging in close-up on his untroubled face flying through town, the Dardennes uncover a youthful desire for freedom which no adult can harness.

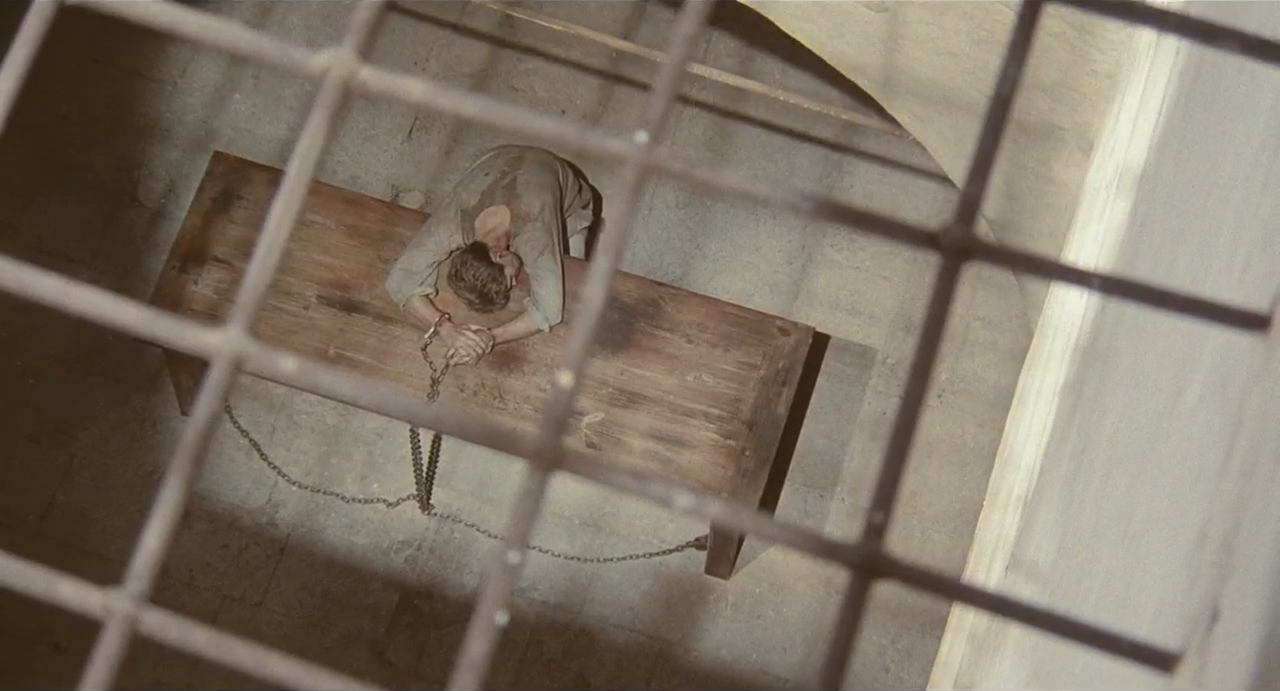

That goes for his father too, who squanders every opportunity to model upstanding behaviour. Roger will easily transition from beating up his son and then continue working on his tattoo in an instant, and in tying these two acts together we find a powerful representation of his desire to make another man in his own image. Igor searches for guidance, but all he finds is his father’s warped direction, obliterating the intimacy of family by asking to be called Roger rather than Dad, thereby making his denial of responsibility just a little easier. This means that when Hamidou, an undocumented immigrant they have been exploiting at work, falls from scaffolding in a panicked attempt to hide from inspectors, Roger has no issue getting Igor to help cover it up. In this instance they are not a father and son, but merely just work buddies, equally culpable for the ‘accident’ that has occurred.

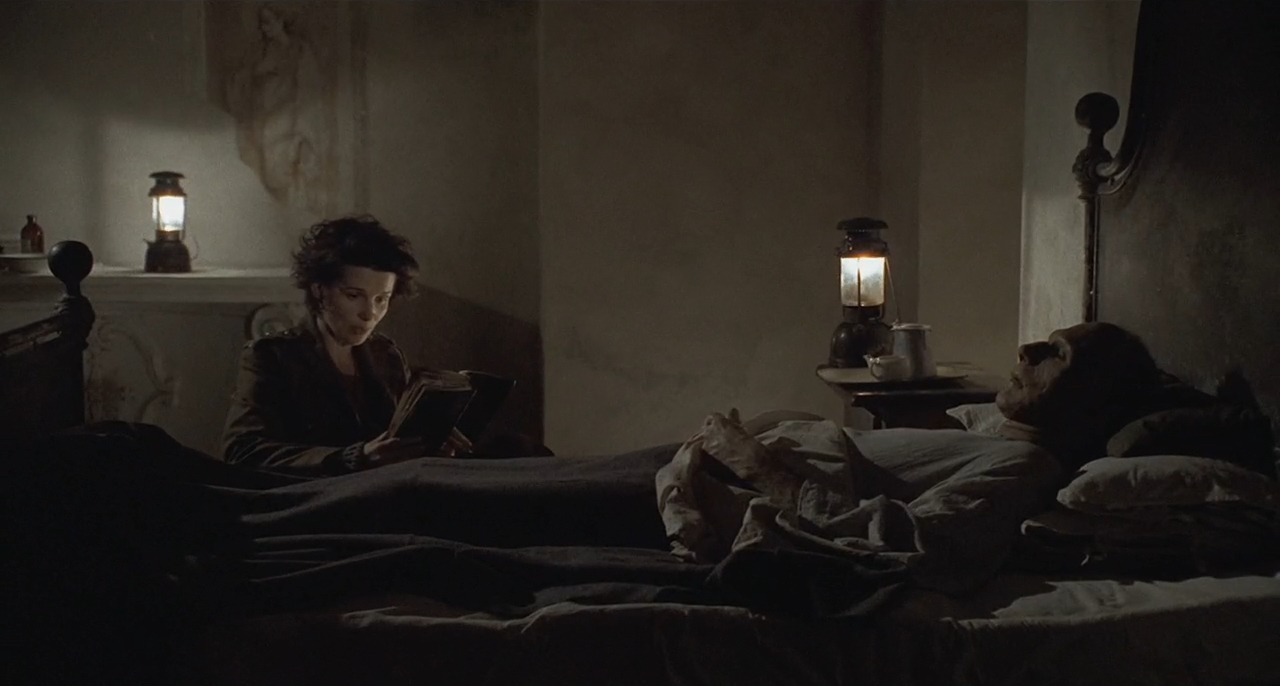

The bonds we hold to others can be tricky though, and Igor quickly discovers this when a dying Hamidou makes him promise to look after his family, directly conflicting with the loyalty he has to his father. This is the dilemma upon which La Promesse pivots its entire drama, holding us in the grip of Igor’s torn mind as he tries to figure out compromises between the two.

Back home, Hamidou’s wife, Assita, speculates that he has run away due to gambling debts, and for a while Igor can entertain this theory, even setting up a co-worker to drop off 1000 francs under the guise of repayment. Really though, measures like these to soothe her worries are only temporary. Doubts keep creeping back into her mind, seeing her resort to traditional African divination readings from chicken entrails and a local seer to provide the truth of the matter. It is a strange dose of mysticism the Dardennes inject here, obscuring our view of the whole situation with the consideration that there may be some grander, divine force at work. These readings are never precise enough to convince us of their truth, but neither are they entirely inaccurate, with the seer sensing the rage of justice-seeking ancestors in Assita’s sick baby. Whether this is real or not may not even matter – the diagnosis haunts Igor all the same, pinning the baby’s fever on him and driving him deeper into his own guilt.

It is a bitter, unjust society which these characters persevere through, persecuting them systematically, as we see in Roger’s attempt to sell Assita off as a prostitute, as well as in bouts of random cruelty, typified by the two strangers urinating on her for their own entertainment. The Dardennes are no great cinematic stylists, but their grainy 16mm film stock, handheld camera, and long takes do serve to underscore the pure joylessness of this setting, sitting in the back of cars and holding tightly on Igor’s face as he crumbles under pressure. Any actor would be envious of a debut performance as vividly pained as this, as Jérémie Renier bears the gradually increasing strain of Igor’s predicament with discomposed weariness.

His final, decisive action does not come as a shock, but the timing is certainly unexpected. There are no didactic monologues or urgent stakes pushing Igor to come clean – just the slow, mounting shame weighing on his conscience, spilling the truth out in a train station after a long, burdensome silence. The Dardennes land this ending with precision, resisting the urge to have Assita respond with anything other than a resolute turn around and walk back into town, now reinforced in her mission by the answers she has so desperately sought.

Lesser filmmakers might have hinted a little at the aftermath, though it is insignificant here for two reasons – this is the point where the story is is no longer purely in Igor’s hands, and it is also where he decisively puts his stake in the ground, resolving to be a man with integrity rather than a passive bystander. La Promesse is not about a death, a lie, or a fight for justice, though the messiness of each are unavoidable. It is about the promise a boy makes to be better than the world around him, starting with the sworn oath itself, and ending with his first step towards fulfilling it.

La Promesse is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.