Sergio Leone | 1hr 39min

When the Stranger first arrives in the rural border town of San Miguel, the reception from its locals is foreboding. A noose hangs from a withered tree, warning visitors away from the lawless justice that runs rampant. From a distance, he observes a small child trying to sneak into a building, only to be kicked out and shot at as he runs back to his mother. As he rides down the street, the civilians aren’t much friendlier to him either. “I reckon he picked the wrong trail,” one mouthy bandit scoffs. “Or he could have picked the wrong town,” his companion retorts, before their small gang sends the Stranger’s galloping off in a panic.

It only takes a couple of minutes for our hero to deliver fierce retribution. With four swift gunshots, he wins the quick draw against their entire crew, and sends them to early graves. It is also in this moment that we see three separate artists make their first major step towards culture-defining excellence.

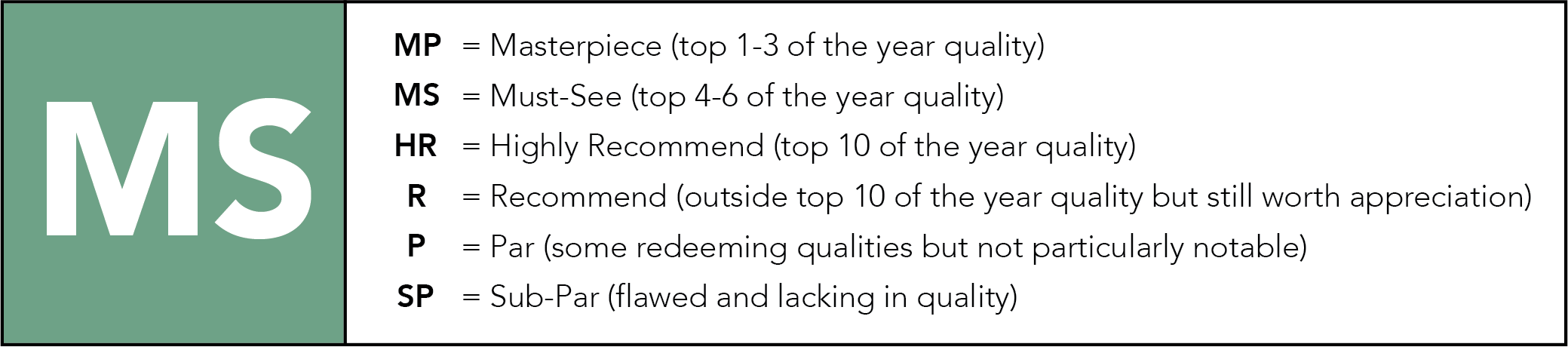

As the Stranger stands alone in his poncho against a daunting arrangement of outlaws along a wooden fence, Sergio Leone’s fine orchestration of his editing and staging ominously build their interaction to an impasse, before shattering the tension with an angry, violent bloodbath. This sequence was not only a resounding artistic breakthrough, but also marked the beginning of the Western genre’s most significant shake-up to date. Where America sought to define its own national mythology through fables of good vs evil, Leone’s importation of these archetypes into Italy infused them with a harsher, grittier edge, cynically leaning into the moral grey areas of history that never found easy resolutions. Perhaps even more impactful on his style though was the cinematic nihilism of Akira Kurosawa, with samurai film Yojimbo providing the narrative template upon which A Fistful of Dollars is based.

Also key to this pivotal scene are the distinctive musical cues of Ennio Morricone – and of course the accompanying silence that he wields with solemn purpose. A sharp, short series of descending notes on a flute accompanies the Stranger’s slight head raise, matching his piercing glare as it emerges from beneath his hat brim, and a high-pitched whining on strings carries us all the way to the inevitable gunfire. From there, Morricone continues weaving textured layers all through his score for A Fistful of Dollars, creating a sound which in decades to come would be recognised as the quintessential ‘sound’ of the Western genre. Whips crack, bells toll, and male voices chant in robust unison, while underscoring the bold, silent presence of the Stranger with blaring trumpets as he daringly strides into hostile territory.

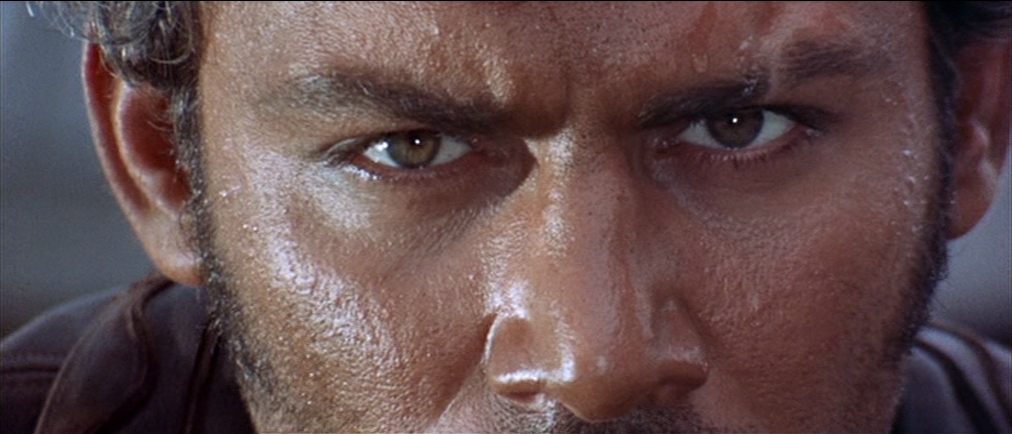

It is impossible to imagine A Fistful of Dollars without either Leone or Morricone at the helm, but the final part of their trio would in time become the face of Spaghetti Westerns, and eventually transcend even that niche. Clint Eastwood’s screen presence is undeniable as the Stranger, squinting into glary landscapes and mumbling past a cigar that sits in the corner of his mouth. Faced with a town that is split between two rival families vying for control, he uses his sharp mind and sharpshooting skills to orchestrate their downfalls, though it is also the mystery that shrouds his stoic demeanour which turns him into such a compelling figure. After all, he is the Man with No Name, unbeholden to any title, status, or allegiance. When asked by the captive Marisol why he is helping her escaping the factions she has been traded between, his response is vague, yet hints at a past that has hardened him into an aggrieved, avenging angel.

“Because I knew someone like you once. There was no one there to help.”

This is a man driven by an internal sense of right and wrong, and Leone holds no regard for whether we believe he goes too far in certain instances. His quick anger and readiness to kill mars the image of the classic Western hero upheld by Hollywood throughout its Golden Age, yet he is nevertheless the closest thing to a saviour that San Miguel has. Even after being brutally beaten by his enemies, still he refuses to yield, instead recuperating in a cave and eventually being reborn from it as a Christ figure destined to deliver the town from evil.

After all, the feud which divides San Miguel is deeply entwined with matters of prejudice, greed, and corruption. On one side, the Mexican Rojo brothers control the flow of liquor, while the white American Baxter family smuggle guns across the nearby border. Outside of both, the Stranger proves his wits in outsmarting them equally, spreading a rumour in the wake of a recent assault from the Rojos that two survivors escaped and are willing to testify against their attackers. After he props a pair of exhumed corpses against a gravestone outside town to appear alive, both families race to the cemetery and engage in a gunfight, shooting the ‘survivors’ in the process.

The distraction couldn’t have worked better for the Stranger. This is the opportunity he needed to empty the town and poke around the Rojos’ base, which Leone deftly intercuts with the battle he instigated unfolding several miles away.

It is ultimately this mutual, self-destructive hostility between the clans of San Miguel which sets in motion their own demise. Falsely believing that the Baxters helped the Stranger free Marisol from their grip, the Rojos retaliate with unrelenting fury, setting their house on fire and mercilessly massacring those who try to escape. If it weren’t for this display of utter cruelty, perhaps the Stranger’s attempt to dismantle these corrupt power structures might have been a little more forgiving. Now as they sadistically torture his closest ally Silvanito out in the open though, Eastwood projects a ferocity unlike anything we have seen from him before, commanding a wide shot that establishes him as the true law and order of this town.

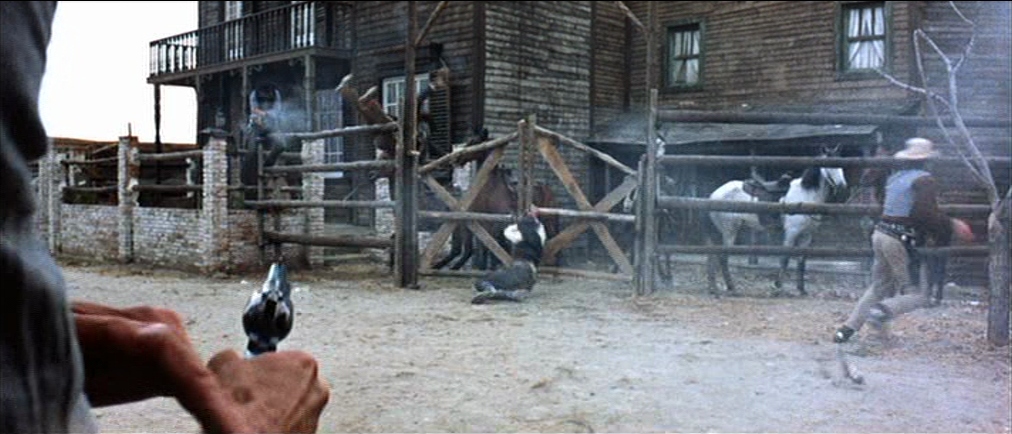

Bullets cannot harm him as he fearlessly strides down the main road to face his would-be killers, instead lodging in the handmade plate armour protecting his torso. The rhythmic, accelerating pace of Leone’s montage, Morricone’s score, and the magnificent blocking of actors once again drive up the tension, though with a few added camera zooms and extreme close-ups studying each bead of sweat, the suspense also becomes unflinchingly visceral. With six gunshots, the Stranger disarms the leader Ramón, and dispatches his band of cronies. With a seventh, he severs the rope binding Silvanito’s wrists, and after challenging Ramón to a quick draw, the eighth takes his life.

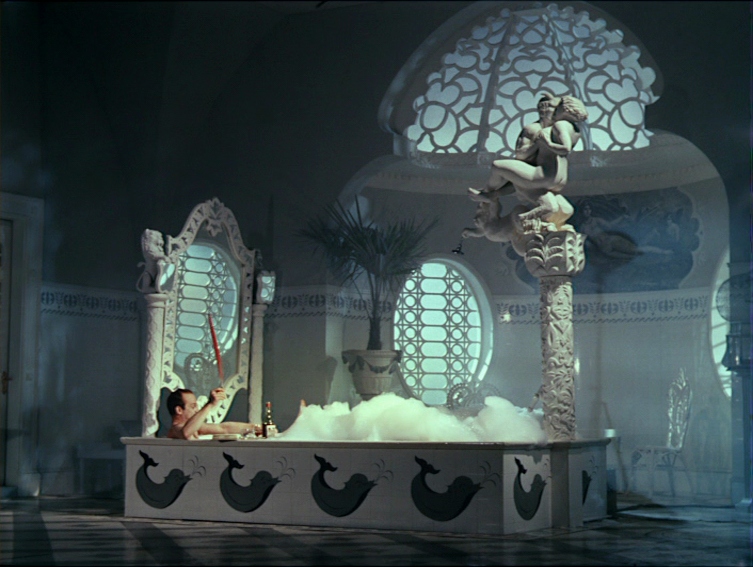

In using every cinematic element at his disposal to craft suspense and set pieces, Leone stands right next to a select few elite filmmakers in cinema history, including both Hitchcock and Kurosawa. Even outside of these gripping sequences though, A Fistful of Dollars also reveals his magnificent command of establishing shots, particularly using Techniscope technology to stretch vast, dusty landscapes across a wide canvas and draw dynamic compositions from beautifully designed interiors. When the arresting majesty of his crane shots is considered next to his creative framing of faces, Leone can’t help but reveal the influence of D.W. Griffith in his camerawork as well, proving his similarly extraordinary mastery in capturing both the epic and the intimate.

The cumulative result of such varied techniques is operatic, serving a narrative that carries a far greater scope than its 100-minute runtime would suggest. Next to such grand achievements, the awful voice dubbing in A Fistful of Dollars barely warrants a mention, besides an appreciation for Leone and his crew’s perseverance through such a trying production. It seems that all it took to push the genre forward was the voice of an outsider who had never stepped foot in America, yet nevertheless had the talent and vision to cynically undermine its revered mythology, delivering a portrait of the Old West drenched in blood, sweat, and violent anarchy.

A Fistful of Dollars is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.