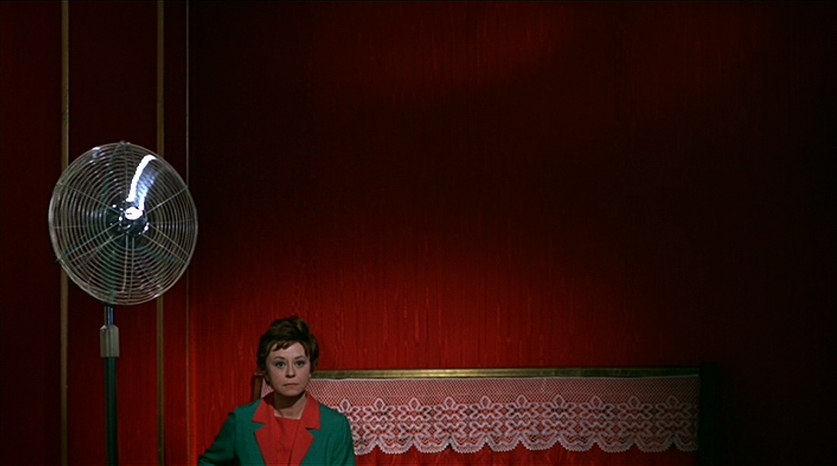

An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

If Yasujirō Ozu’s filmography is a cinematic suite charting the tension between tradition and progress, then An Autumn Afternoon stands as a tender final movement, tracing a widowed father’s reluctant push to marry off his daughter amid Japan’s mid-century commercialism.