Jean Renoir | 1hr 35min

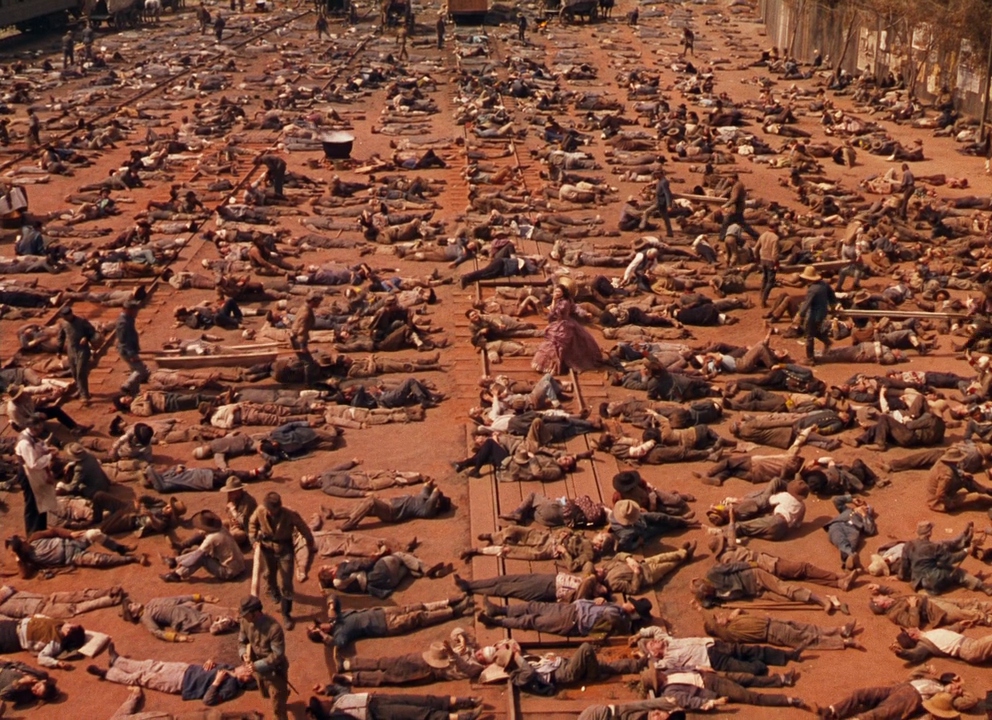

So tragically naïve is aspiring painter Maurice Legrand’s tale that Jean Renoir does not even let his demeaning fall from grace speak for itself in La Chienne, but rather frames it within the humiliating confines of a Punch and Judy puppet show. “The play we shall perform is neither drama nor comedy,” our wood-and-felt narrator explains. “The characters are neither heroes nor villains. They’re plain folk like you and me.” Indeed, the super-imposed images of Maurice, his mistress Lulu, and her pimp Dédé take their place upon this tiny stage like figurines playing the roles assigned to them by some invisible force – perhaps a cosmic power that has already written out their fates, or maybe a humble storyteller who lingers just outside the frame.

Either way, there are some inevitable misfortunes that simply have no regard for whether one might consider themselves a good person or not. Maurice is a laughingstock among his peers, so timid that he is even overshadowed by the portrait of his wife Adele’s seemingly deceased first husband on display in his home. Nevertheless, a crack in the moral fortitude of a righteous yet weak-willed man is an opening for corruption to plant its seed. There are simply no winners to be found in Renoir’s adaptation of this French novel, especially when the storyteller deems all characters to be equally undeserving of happiness.

With La Chienne kicking off Renoir’s magnificent 1930s run, this moral fable set the wheels of France’s poetic realism in motion, weaving lyrical musings on romance and despair through Maurice, Lulu, and Dédé’s love triangle. Besides a few effective uses of stark light and shadow, it does not possess the visual harshness of German Expressionism, but rather bridges the gap between that cinematic movement and Hollywood’s film noir with its brooding fatalism and seductive femme fatale. Fourteen years later in 1945, Fritz Lang would even adapt the same literary source material in Scarlet Street, shooting in darkened studio sets modelled after New York rather than around the bright streets and buildings of Paris.

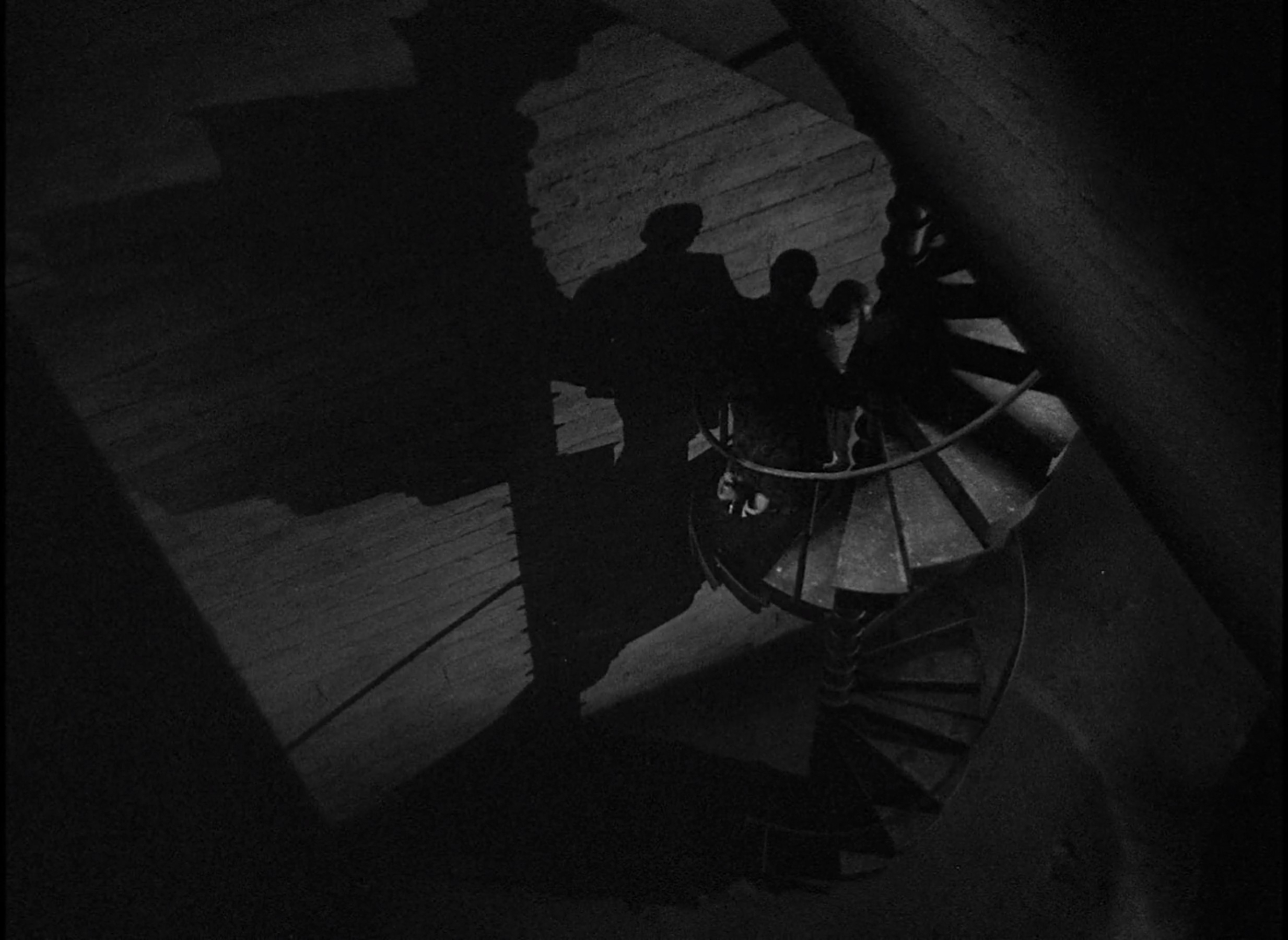

The transitory nature of La Chienne’s production is only further underscored by the recent advent of synchronous sound in film, though one wouldn’t guess this was an issue for Renoir given the way his camera completely disregards the cumbersome audio equipment, preferring to glide into new frames rather than cut away. These delicate movements demonstrate a boundless creativity, rising with a dumbwaiter into the dining hall where Maurice’s tale begins, drifting past a row of laughing guests, and settling on the pouty face of our milquetoast protagonist. When we later visit Lulu and Dédé plotting how best to take advantage of this poor fool during a lively waltz, Renoir conversely distinguishes their passion with a kinetic burst of energy, displaying an early instance of handheld camerawork as we rock and sway with their dance.

The plan to milk Maurice of his money is thus set in motion, seeing Lulu claim his paintings as her own and remarkably find far greater commercial success. The trust that he places in her is pitiful, compelling him to look past the light that is suspiciously turned on in her apartment when she isn’t home, though we can’t feel too sorry for him either. Within the meekness of Michel Simon’s performance is a self-serving cowardice that particularly emerges when he breaks up with Adele, choosing to stage a cruel reveal that her first husband is in fact alive, rather than simply owning up to his infidelity.

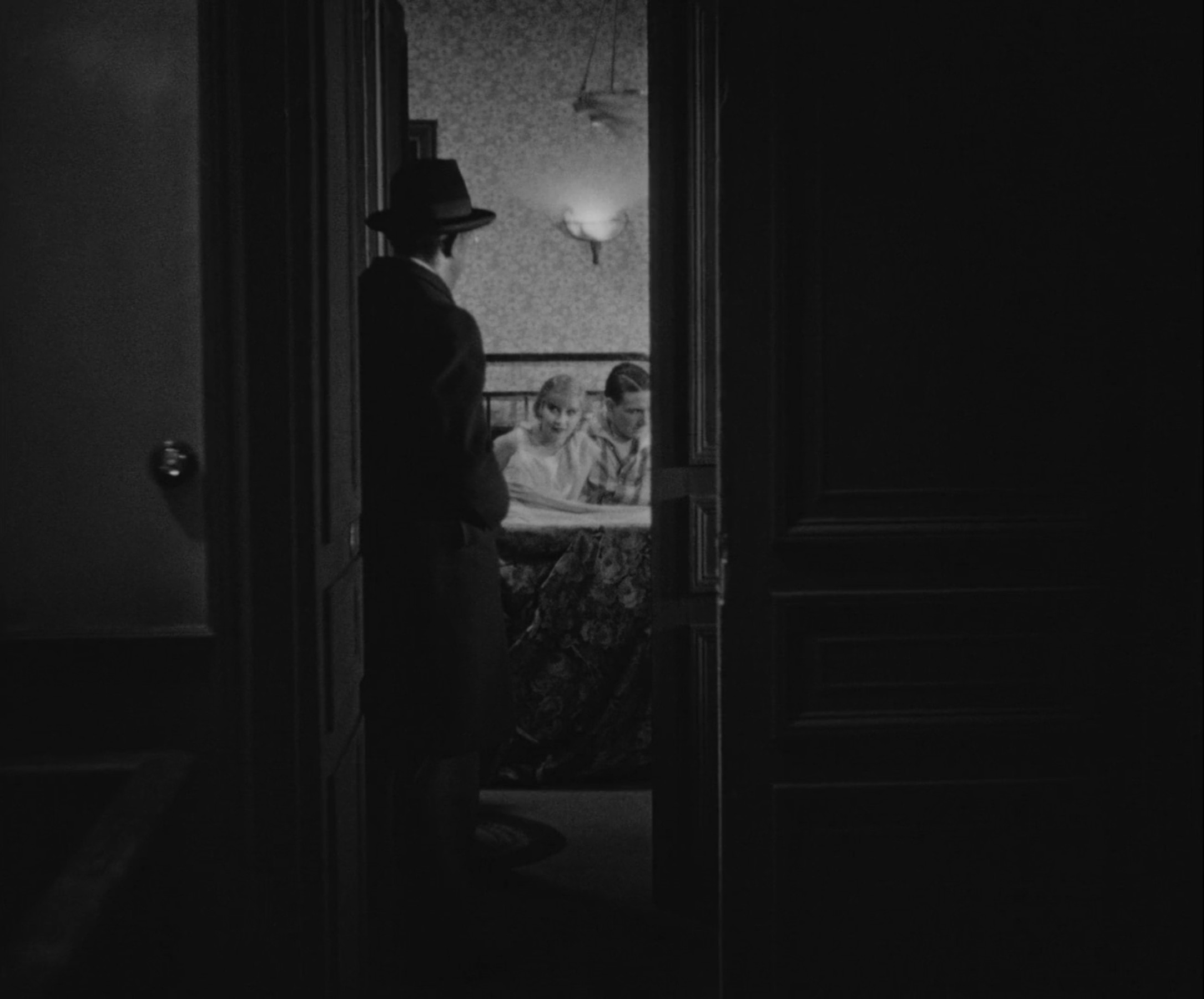

Renoir’s blocking of this pivotal moment arrives with a gorgeous flourish as Adele and her astonished neighbours direct their eyes towards a doorframe bordered with patterned wallpaper, within which stands a living-and-breathing Alexis. This pairing of deep focus photography with structural frames continues to mark significant plot beats from there, notably including one devastating turning point that leaves a sliver of Lulu and Dédé visible through a doorway largely obstructed by Maurice’s body, frozen in shock at discovering them in bed together.

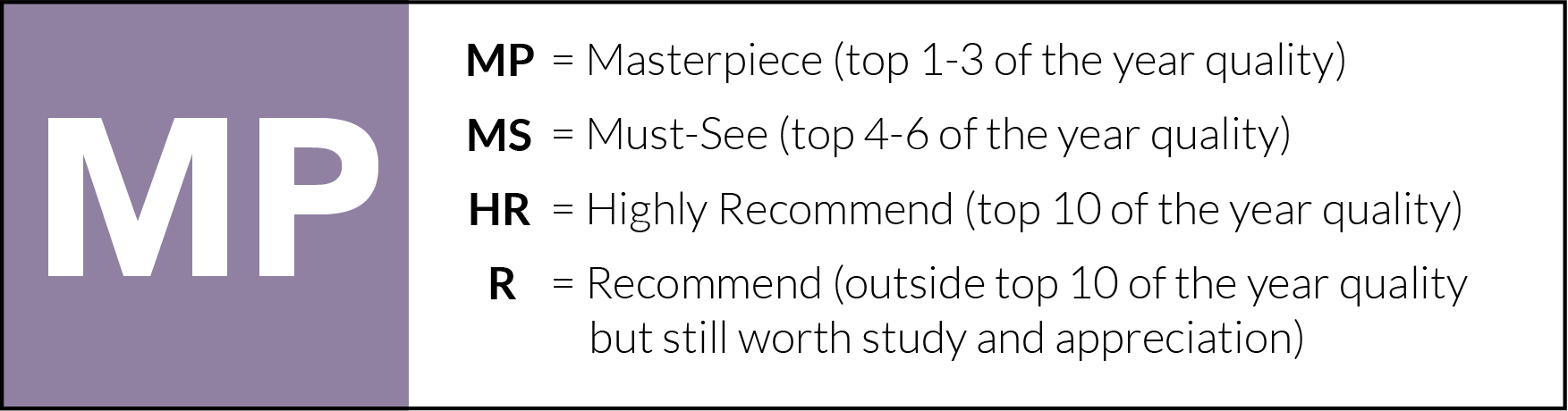

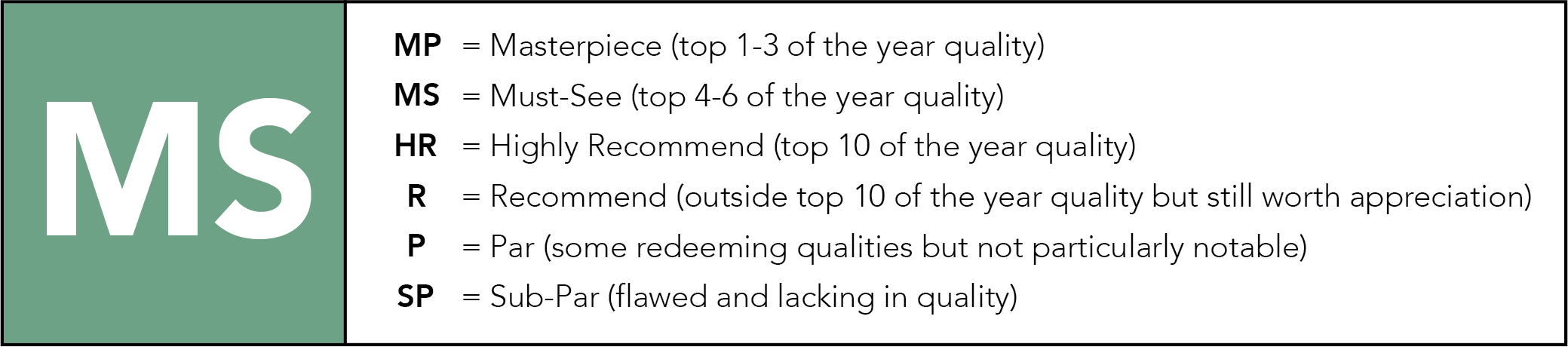

The window of Lulu’s apartment also makes for a series of stunning compositions in La Chienne, delicately framing her and Maurice’s romantic encounters behind a row of flowers sitting just outside, and delivering a Brechtian reminder of the puppet stage that this entire story is staged upon. When it appears in the first two instances, it is formally associated with Maurice’s tender devotion, though when we return for the last time it is tragically corrupted. As the camera climbs up the side of the apartment building and continues through this frame, Renoir’s camera finally settles on a truly horrific scene – the brutal distortion of Maurice’s love into a murderous rage.

That this failed painter so easily escapes suspicion throughout the police investigation that follows is a testament to the community’s total disregard for him, unable to even tease the idea that he is capable of such a vile act. Despite Dédé being innocent for once, it simply makes far more sense to pin this crime on the widely-loathed pimp, especially since he was unlucky enough to be witnessed coincidentally visiting the murder scene around the time of Lulu’s demise.

Just as Lulu’s fate led her to the end of blade and Dédé’s to a public execution for a crime he never committed, Maurice is doomed to suffer a humiliation greater than he has ever known. Death would be preferable to this personal hell living as a haggled tramp on the streets without any work or wife, and even he acknowledges as much when he learns of Adele’s passing some years later. Having lost all dignity, there are few people who believe the words of a madman claiming responsibility for a murder that has already been solved, and those who do care little anyway.

Meanwhile, the artistic greatness that Maurice was secretly capable of is being sold for a fortune just down the street, still being attributed to the woman he killed – a prodigious painter whose life, in the eyes of the public, was taken far too soon. With his matted beard and tattered clothes, he is unrecognisable in the old self-portrait now being carried away by a customer dropping a measly 20 francs behind them as they leave. As Maurice scrabbles to pick it up, he barely even considers that this is the first and only time he has effectively received money for one of his artworks, and neither does he register the meagreness of the sum compared to what it has sold for. The meal that it will secure is good enough for our humbled antihero, now effectively rendered more invisible than ever as Renoir draws the curtains on this fable, and accepting his place as a mere puppet on life’s stage of poetic irony.

La Chienne is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to purchase from Amazon.