Yasujirō Ozu | 47 min

Secrets exist for good reason in Woman of Tokyo, maintaining the equilibrium which defines clear relationships between siblings, lovers, and colleagues. The first time Chikako encounters a threat to this balance though, it arrives in her office, where she has worked diligently for four years as a typist. The police presence is unexpected, as are their probing questions to her boss, asking for employment records and general opinions of her character. There is nothing to report there, the manager says. Her attendance has been impeccable, she is dedicated to her younger brother Ryoichi, and after hours she even helps a professor with his work.

At the mention of her extracurricular activity, the officer perks up, though it isn’t until later when rumours begin to spread that we find out why. Chikako works as a prostitute at a seedy bar, officer Kinoshita informs his sister Harue, who also happens to be dating Ryoichi. When this gossip eventually reaches his ears too, there is little that can hold back his destructive fury.

The fact that Woman of Tokyo lands among Yasujirō Ozu’s shorter films does not make it any less than a complete work, even if tends to skim the surface of its characters. Despite its brevity, this tragedy fully realises the melodrama of its premise, challenging the conservative cultural norms of the era represented in Ryoichi. Prostitution is so dishonourable that he initially refuses to believe the rumour, and impulsively breaks up with Harue for even entertaining its truth. “Anyone who disturbs our peaceful life is my enemy!” he imperatively declares, though the dialogue here comes off as forced to say the least.

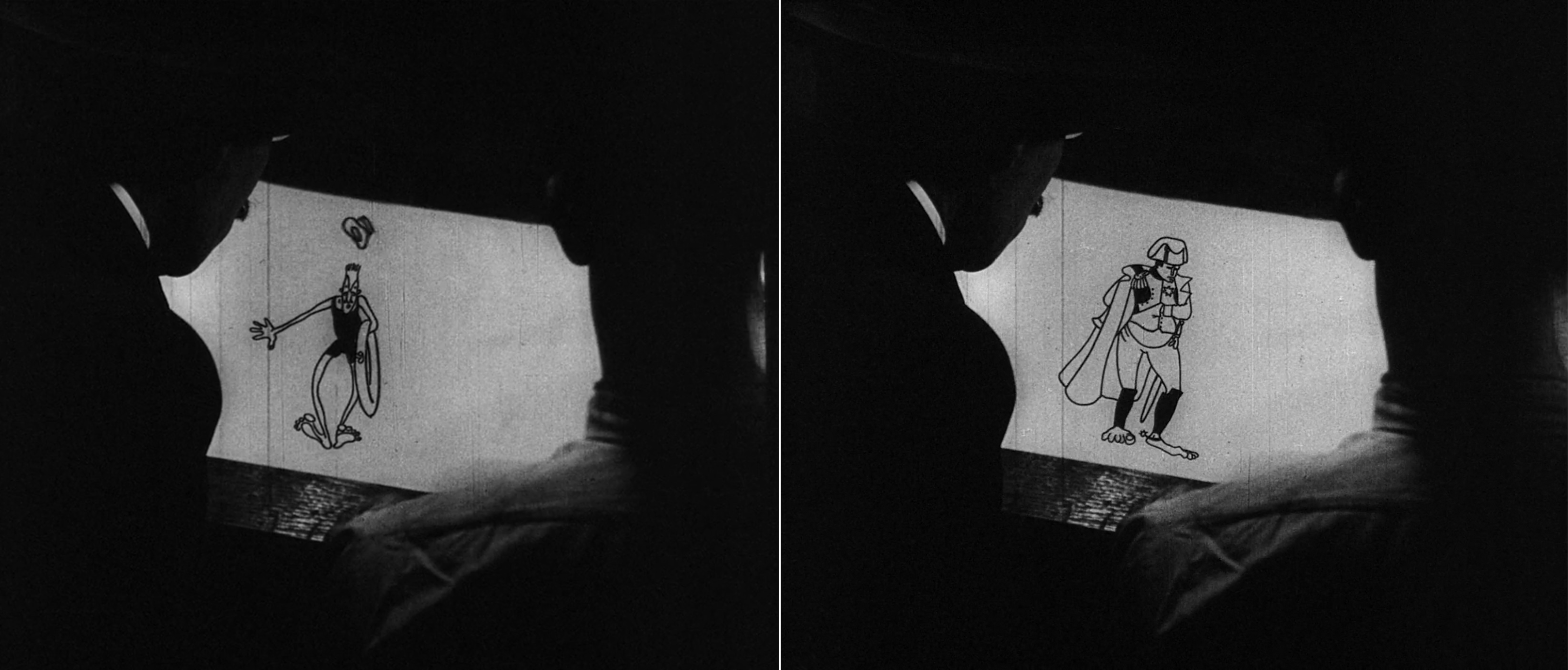

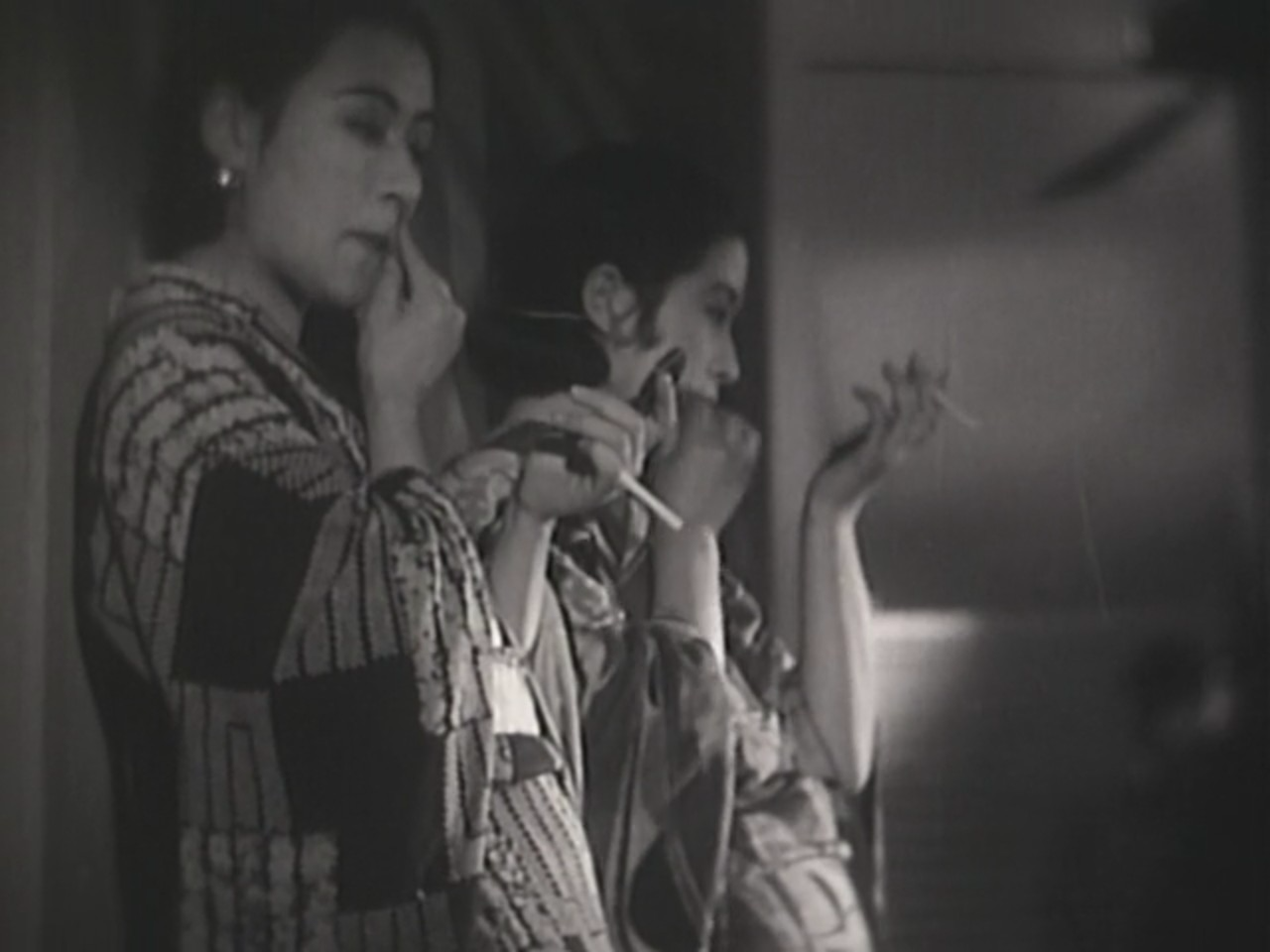

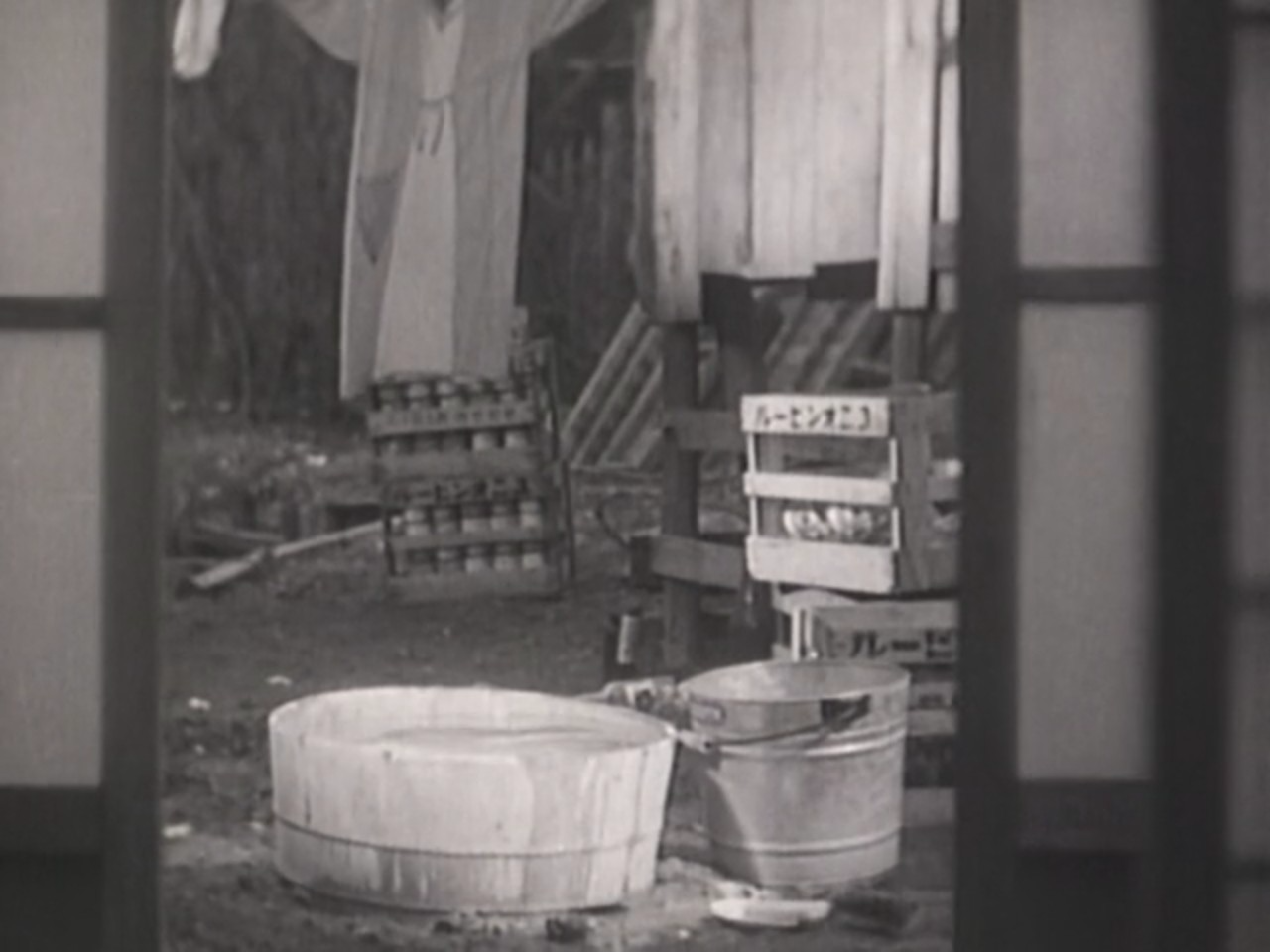

Subtlety and suggestion are usually among Ozu’s most effective tools as a storyteller, so it is through his editing rather than his writing where these qualities flourish in Woman of Tokyo. His admiration of Ernst Lubitsch’s elegant ‘touch’ manifests directly in an early scene where Ryoichi and Harue watch If I Had a Million at the movie theatre, and it also takes cinematic form in the rhythms of his delicate montages, directing our focus to the domestic minutia of Chikako and Ryoichi’s house. The rotating cowl, chimney, and kettle become recurring visual motifs here, with the latter especially being used to illustrate steaming pressure and quiet tension between siblings. As Ryoichi’s thoughts darken with deeper consideration of Harue’s accusation, so too does the lighting dim, underscoring a brutal confrontation that ends with bitterness, heartbreak, and a regrettable slap.

Ryoichi’s sudden departure concerns both women, and for good reason. Still Ozu keeps track of that kettle, boiling with anticipation, and now the dripping water from hanging laundry joins in like a ticking second hand. When Harue takes the call to learn of her boyfriend’s fate, the clocks decorating the wall behind her build that steady rhythm to a chorus, counting down to irrevocable tragedy. He has taken his life, Kinoshita informs her over the phone, and Ozu’s cutaway to the shadow of a noose upon a wall tells us all we need to know.

Woman of Tokyo is not some ham-fisted moral lesson about honouring one’s family though, but rather dwells in Chikako’s mournful anger. “You had to die for this?” she laments over his body, tearfully calling out the futility of such an extreme response.

“You coward, Ryoichi.”

The epilogue which follows a pair of reporters into the street makes for a clumsy formal misstep, reframing Chikako’s grief within a capricious news cycle. For a young Ozu who was not yet at the top of his game though, such flaws are merely part of his awkward transition from genre films to humanistic dramas, where his graceful, restrained storytelling would soon blossom. Woman of Tokyo does not deliver the formal impact of his later masterpieces, yet there is nevertheless a precision in its dramatic tension and release, glimpsing the quiet devastation that lies beneath domestic stability.

Woman of Tokyo is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.