Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 31min

The lingering cadence which brings the film title I Was Born, But… to an open-ended ellipsis seems to raise a question. The simple innocence that comes with infancy doesn’t hang around for particularly long after we venture beyond our family homes – so as children, what might we expect from a world that contains power dynamics far more complex than our immature minds can comprehend? Through Yasujirō Ozu’s patient eyes, this deliberation only deepens with age, not so much granting answers as it reveals the sheer commonality of imbalanced relationships through all stages of life. With gentle humour and formal acuity, I Was Born, But… contemplates such social patterns across two generations of a Japanese family, and delicately ponders the potential to break its pitiful cycles.

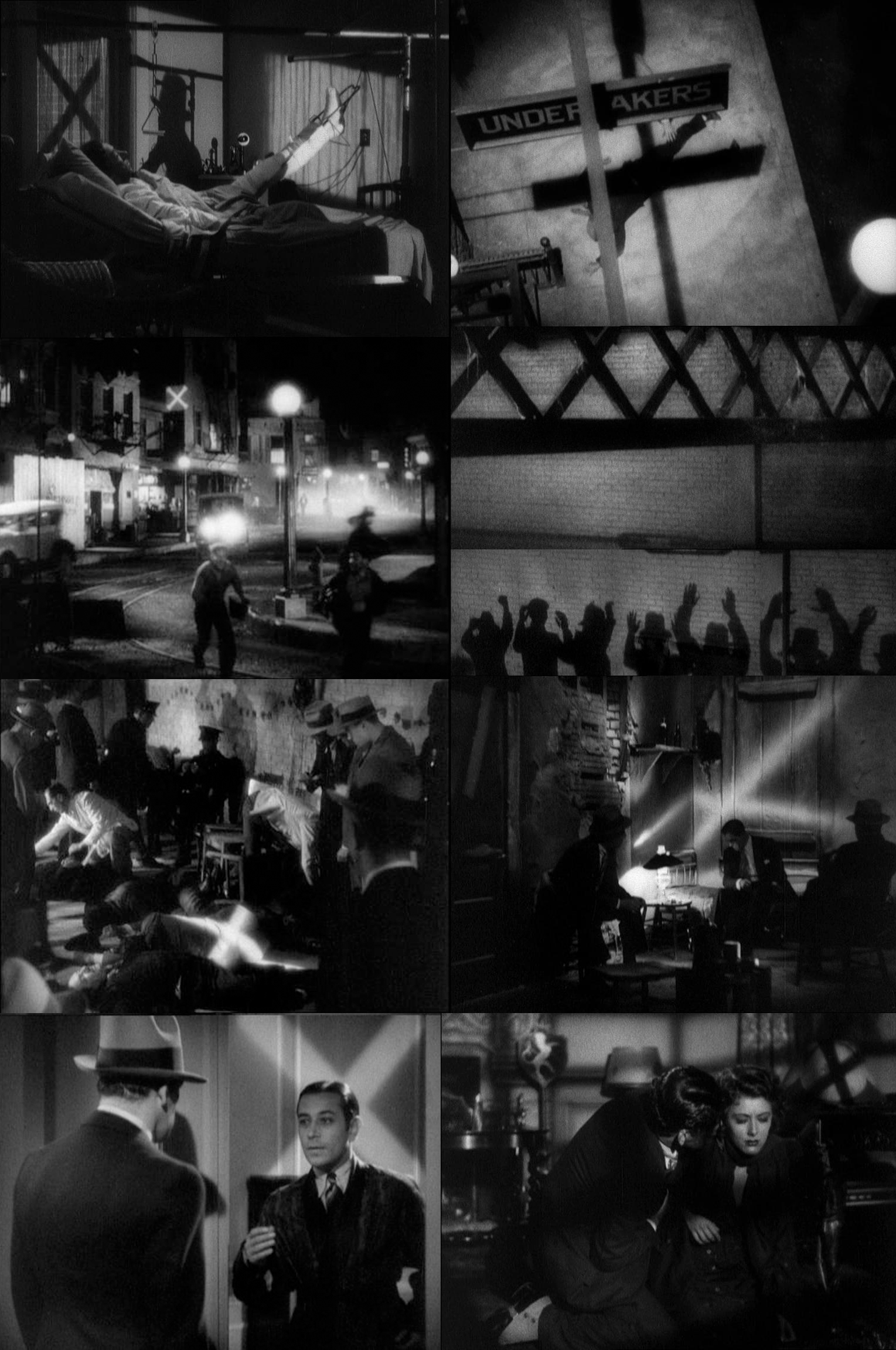

Brothers Keiji and Ryoichi are virtually copies of each other here, disorientated by their family’s sudden relocation to the Tokyo suburbs and sudden enrolment in a new school, yet still finding the time to get tangled up in mischief. Still working in the realm of silent cinema, Ozu borrows the light-hearted deadpan of Hollywood’s early comedians to pace their story, pitting the two boys against a local gang and their leader Taro who scares them away from attending school. With their father Chichi setting high academic expectations, they spend the day forging homework and grades to escape his ire – so it is unfortunate indeed that he remains well-informed through his boss Iwasaki, Taro’s father.

At least with the help of older delivery boy Kozou, Keiji and Ryoichi are able to gain some ground against their bully, even forming somewhat of a friendly rivalry with him and his cronies. “My dad’s got lots of suits,” one boy competitively proclaims. “My dad’s car is fancier” and “My dad’s the most important,” the others pile on, trying to raise their own status through association with their fathers. At Iwasaki and Taro’s home video night though, it quickly becomes clear whose is most definitively not at the top of the pecking order.

At this gathering, a whole new world of office politics is revealed to the brothers. As adults and children sit down to watch Iwasaki’s recordings, Chichi’s stern, authoritative image dissolves in their eyes, replaced by that of a clownish buffoon sucking up to his boss. “You tell us to become somebody, but you’re nobody!” they rebuke, and all of a sudden Ozu brings into focus the incredible similarities between their respective worlds.

After all, the social and economic barriers which afflict one generation is not so easily cast off by the younger, particularly given the recent relocation both parents and children have been equally affected by. As they walk through their relatively barren neighbourhood, Ozu frequently passes trains through the background, breaking up flat plains with these huge, industrial icons of modernity. Class and status are not merely defined by human relationships – they are right there in their humble surroundings, ever-present in transitory cutaways to telegraph poles and hanging laundry.

The foundations of Ozu’s pillow shots are evidently being laid in I Was Born, But…, though even more pervasive is his subtle yet purposeful positioning of the camera, taking the perspective of a child by setting it no more than just a few feet above the ground. Adults tower over us from this angle, and when Chichi’s disillusioned sons destroy his ego, he too sinks low in the frame to meet us where we sit. His humiliation is felt even further in the Ozu’s visual divisions, isolating him in windows and doorways, and once again affirming the extraordinary artistic mind which would eventually perfect the art of developing character through mise-en-scène.

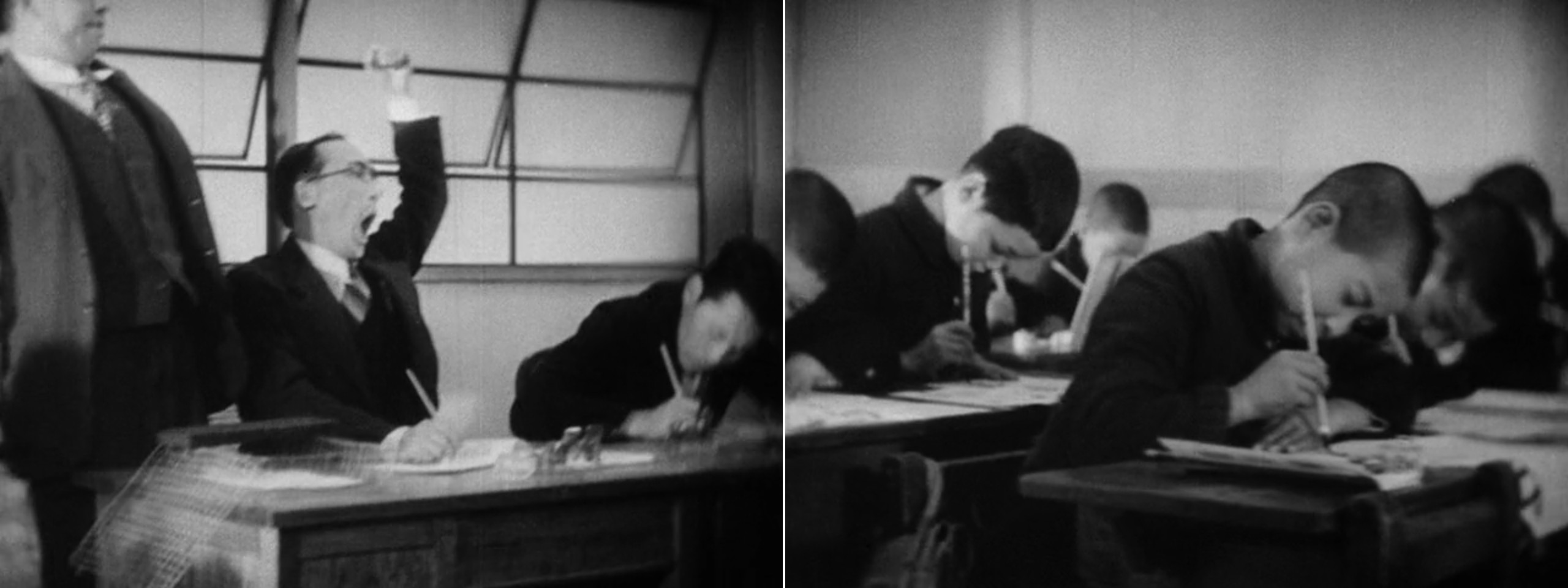

Much more unusual for Ozu is the proliferation of tracking shots on display here, rolling past workers and students alike as they write at their desks. The formal parallels between generations continue to reveal themselves in this stylistic device, trapping both in rigid institutions which require submissive compliance from their subjects, though it is also there where Chichi and his sons diverge in their responses.

Disappointed that their father does not model the same upstanding behaviour he preaches, Keiji and Ryoichi attempt a hunger strike, sitting in the garden and turning their backs to the house. Ozu’s comedy is not patronising, but nevertheless finds levity in the brothers’ endearing synchronicity, eventually giving in to their mother’s rice balls and even opening up to their father once again. “What are you going to be when you grow up?” he tenderly asks, taking a seat next to them. “A lieutenant general,” Keiji responds, reasoning that he can’t be a full lieutenant since that will be Ryoichi’s job. Even if Chichi isn’t the perfect image of a respected family man, still there remains a childlike hope that their spirits will not be crushed in the same way.

Then again, can we really judge a father based on the subjective opinions of their children? “Who’s got the best dad, you or us?” Ryoichi asks Taro, continuing their petty competition. “You do,” his new friend answers after some hesitation. “No, you do,” Ryoichi responds in confusion – but really, the different is negligible. These men and boys are simply doing their best navigating the pressures of families and peers, trying to find external validation while remaining true to themselves, and it is there where Ozu grants individuals of all ages equal understanding. Within the messy entanglement of power and status, the formal mirroring of I Was Born, But… reveals that conflict at the root of our common insecurities, as well as the sweet, liberating affirmation we never stop pursuing from infancy through adulthood.

I Was Born, But… is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.