Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 30min

For many great artists, the act of creation comes as second nature, treated like a grand experiment to be dismantled and reconstructed in different forms. For Yasujirō Ozu, it is a practice of intense deliberation and refinement, stoking introspection by mindfully sharpening the tools of one’s craft. This is not to say that he lacks playfulness or humour – one only needs to look at his earliest films to see the influence of Hollywood’s silent comedies after all. Nevertheless, Tokyo Chorus marks a shift in his formal focus. Starting here, he sets off on a journey towards meticulous, cinematic perfection, directing pensive domestic dramas which would define Japanese cinema in decades to come.

Gone are the broad genre strokes which marked Ozu’s prior efforts. In their place, we find the subdued melodrama of a family man whose sudden unemployment tests his personal relationships and wears away at his lively spirit. As it so happens, that streak of wayward defiance has gotten Okajima in trouble ever since he was a student, previously exasperating his schoolteacher Mr. Omura and more recently getting him fired for aggressively defending a laid off colleague. Clearly he never quite learned to demonstrate tact in disagreement, and now as he faces up to the consequences of his insubordination, he must also grapple with the responsibility he holds as a husband and father.

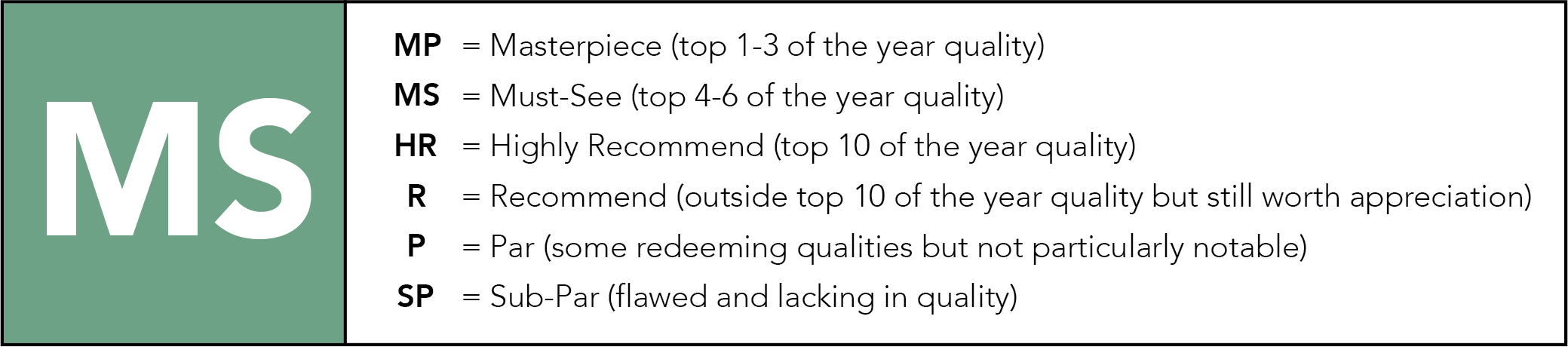

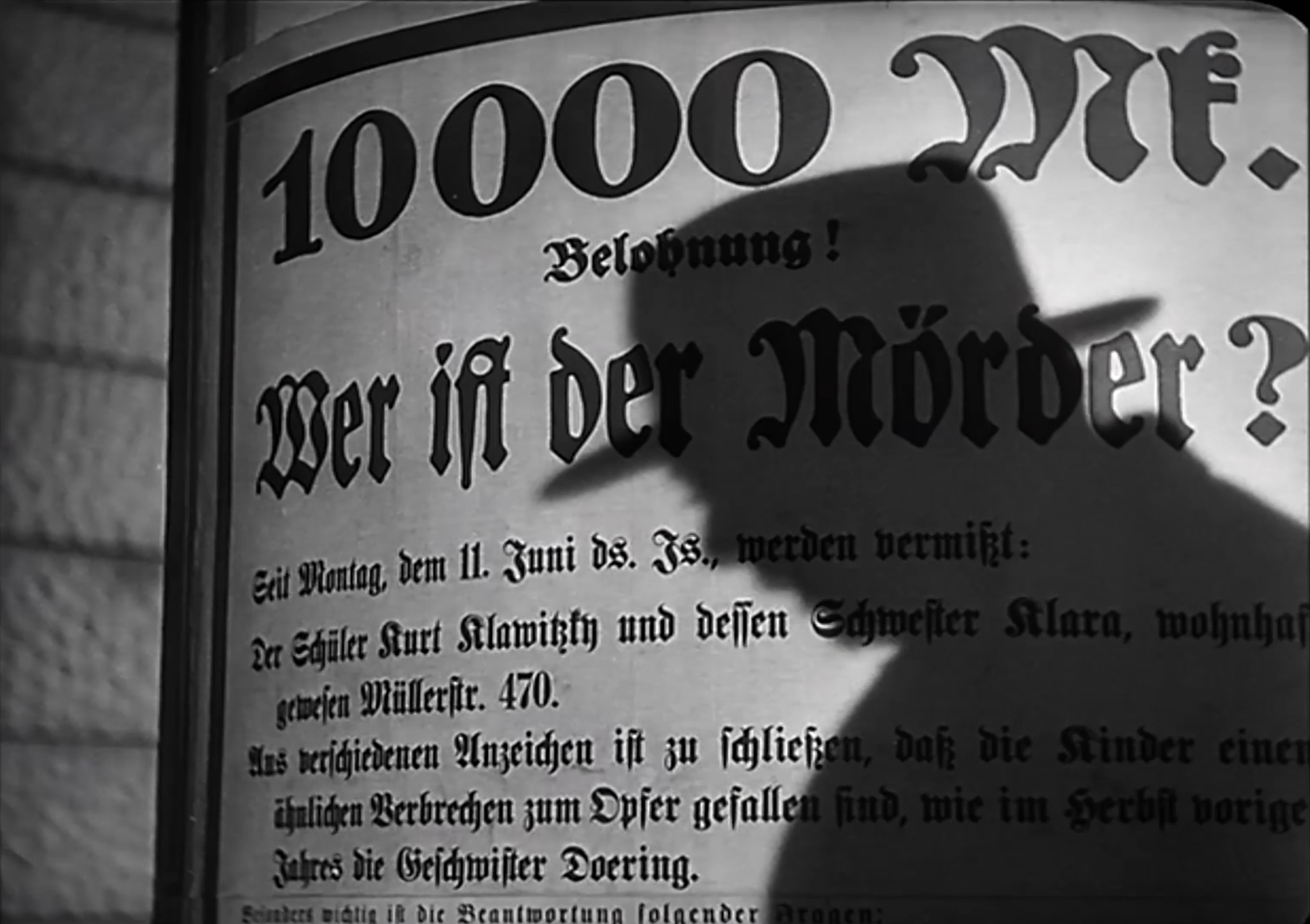

Debuting four years after the advent of synchronised sound in Hollywood, Tokyo Chorus stands as a lingering remnant of the silent era, demonstrating some of Ozu’s finest visual storytelling at this point in his career. His trademark pillow shots aren’t quite fully formed yet, but the cutaway of rustling trees and a torii gate marks a soothing transition away from the prologue, while a montage of typewriters, half-eaten lunches, and empty shoes introduce Okajima’s office momentarily absent of workers.

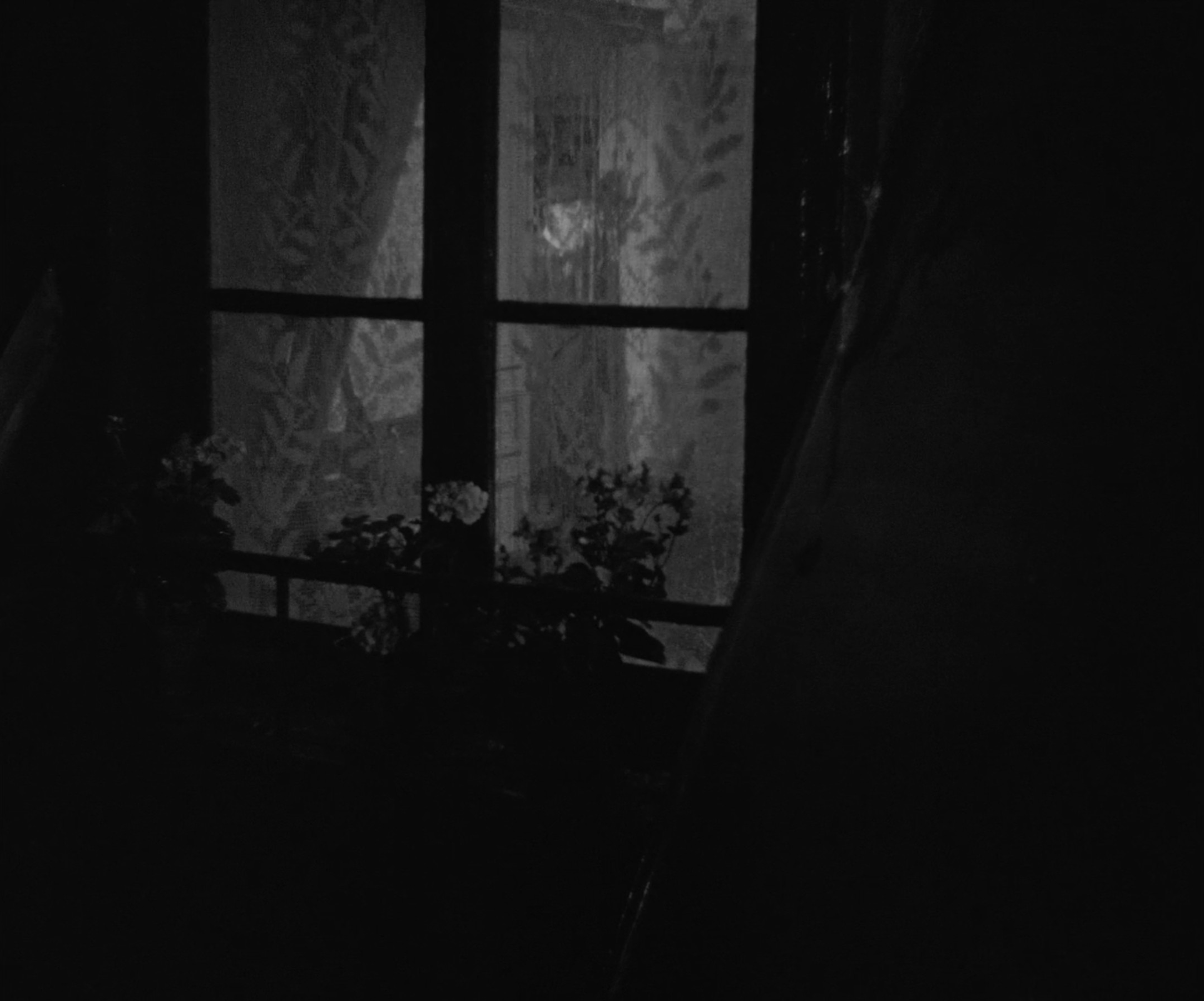

Ozu’s tracking shots certainly bring a sense of order in their straight, unbending lines, but it is very much his editing which sensitively studies the details of these home and work environments, particularly following the hospitalisation of Okajima’s daughter. After selling his wife’s kimonos to pay the bills, their quarrel takes place almost entirely through silent gazes as they playing a clapping game with their children, underscoring the tension with whimsical levity. Actors Tokihiko Okada and Emiko Yagumo must be credited here too for the emotional journey of their facial expressions, bouncing his shame off her disappointment, before uniting in shared joy over their son and daughter. Having separated them in isolating mid-shots, Ozu finally cuts to a wide shot of the entire family playing together, bringing resolution through a moment of forgiveness and understanding.

On a broader level too, Ozu builds Tokyo Chorus around these small cuts to Okajima’s dignity, particularly demoralising him when he cannot afford a bike for his son. The job he finds carrying banners and handing out flyers for The Calorie Café does little to ease his insecurity as well, seeing him bristle at the pity of others, though there is a sweet poetry to the fact that he gets it from a random encounter with his old schoolteacher. Even after retiring and opening a restaurant in his senior years, Mr. Omura still hasn’t quite let go of his fatherly instincts, taking Okajima under his wing once again and promising to help him find work. Ozu allows room for some light comic touches here as Okajima finds himself reliving the days of his youth, obediently marching to the beat of Mr. Omura’s drum, yet still he can’t entirely stave off the creeping depression.

“I feel like I’m getting old. I’ve lost my spirit.”

There is a moral lesson to take from Tokyo Chorus, though Ozu does not deliver it with the overwrought sentimentality of his Hollywood counterparts. Mr. Omura’s gentle, reassuring presence rather stands as a delicate testament to those teachers who don’t just educate us, but become extensions of our families, guiding us with wisdom and purpose through our lowest moments. This tight bond especially reveals itself in Okajima’s class reunion at The Calorie Café, making for a satisfying bookend to Ozu’s narrative, and the job offer which our protagonist finally receives during this gathering makes the moment all the more rewarding.

Still, even amidst the celebration of Okajima’s new vocation as a teacher, there is a lingering sadness in the air as they realise that he must move away from Tokyo. Such is the nature of a student-mentor relationship after all, seeing both men inevitably part ways once the job is finished. Much like Okajima’s silent reconciliation with his wife from earlier though, Ozu again plays out another beautifully edited conversation through nothing but facial expressions, this time between the two men whose eyes sorrowfully drift to the ground while everyone joyfully sings around them. Noticing Mr. Omura’s doleful expression, Okajima offers him a wide, sympathetic grin, and graciously receives one in return. Families of all sorts heal wounded souls in Tokyo Chorus, and as Ozu sharpens his own cinematic skillset, his tender-hearted tribute to those who bring them together marks a moderate yet gratifying step forward.

Tokyo Chorus is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.