William A. Wellman | 2hr 24min

Before there was Best Picture at the Academy Awards, the category was split into two – the Best Unique and Artistic Picture went to expressionist landmark Sunrise at the very first ceremony, while Wings was named the Outstanding Picture. Though the latter film has not established a reputation close to that of its co-winner, holding it to the prodigious standard of silent filmmaking that Sunrise set would not do this technical marvel justice. Wings is a product of a well-oiled studio system exercising its big-budget powers, building the war genre from the ground up, but it is also a display of liberated creativity in William A. Wellman’s magnificent aerial sequences. By taking a birds-eye perspective of humanity’s greatest innovations and devastating injustices, the sheer magnitude of both is baked right into its presentation, heightening the glory and grief of our most monumental ambitions.

More specifically, this tale follows a pair of men who enlist as combat pilots in the Great War, starting off as rivals from the same town fighting for the heart of local girl Sylvia. David is the wealthier of the two who truly has her heart, though aspiring aviator Jack is nonetheless persistent in his efforts to win her affection, remaining ignorant to the advances of his neighbour, Mary. The name she gives his treasured car, ‘Shooting Star’, becomes the same title which he fondly dubs his plane upon arriving at training camp. It is also there that he and David quickly abandon their contempt after a violent brawl, and become close friends.

Before Wellman’s camera lifts us into the sky, he takes the time to lay these character dynamics out across small town America and military camps. While Jack carries Sylvia’s locket and David keeps his childhood bear with him as lucky charms, their tentmate who defies superstition perishes in a crash – an ominous sign of what’s to come further down the line. For now though, Wellman sweeps us along on the energy of training montages and comedic relief, such as the enthusiastic Dutchman who confronts xenophobia by showing off his patriotic star-spangled banner tattoo. Every now and again we got the odd aerial shot looking down from above, though it isn’t until Jack and David themselves take to the “high sea of heaven” for the first time that Wellman unleashes his most inspired cinematography.

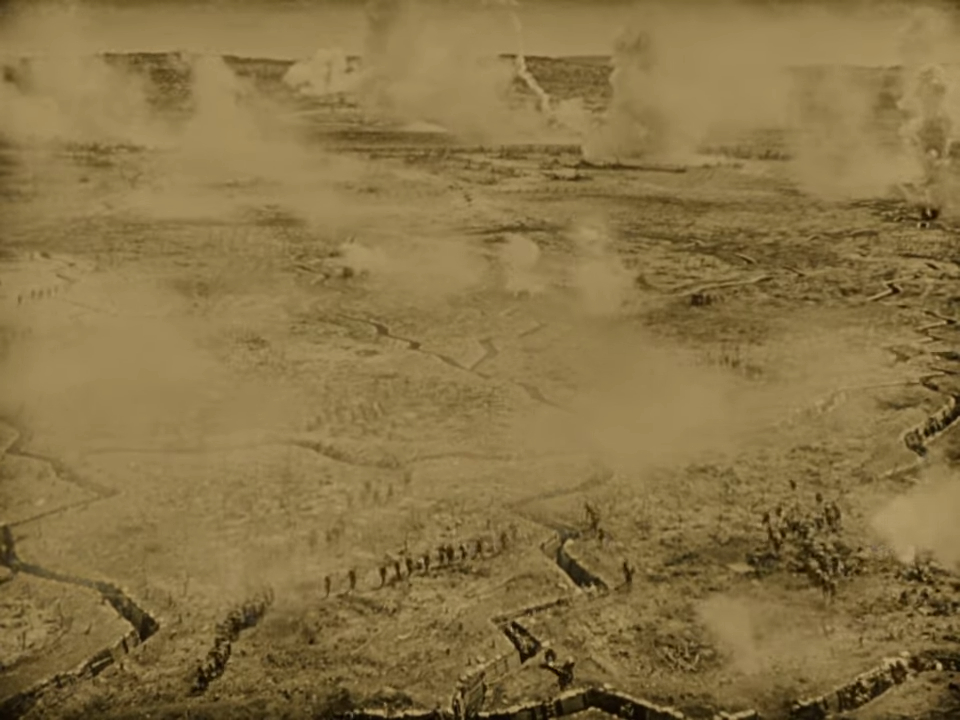

At this point in Wings, it is hard to not draw parallels to Top Gun with its military setting and central male friendship. When it comes to the final act, it even looks as if Top Gun: Maverick has directly lifted the scene of David crashing behind enemy lines and escaping with one of their planes. Most of all though, the strongest influence comes from Wellman’s grand visuals, always seeking the most exhilarating angles to track aerial formations and dogfights. The camera often sits in the cockpit of these scenes, hanging on faces while astonishing backgrounds sway from side to side in deep focus. There is virtually no part of the plane that it isn’t fixed to at some point though, whether being planted on wings or looking from the undercarriage straight down at No Man’s Land as it erupts in explosions and bloodshed.

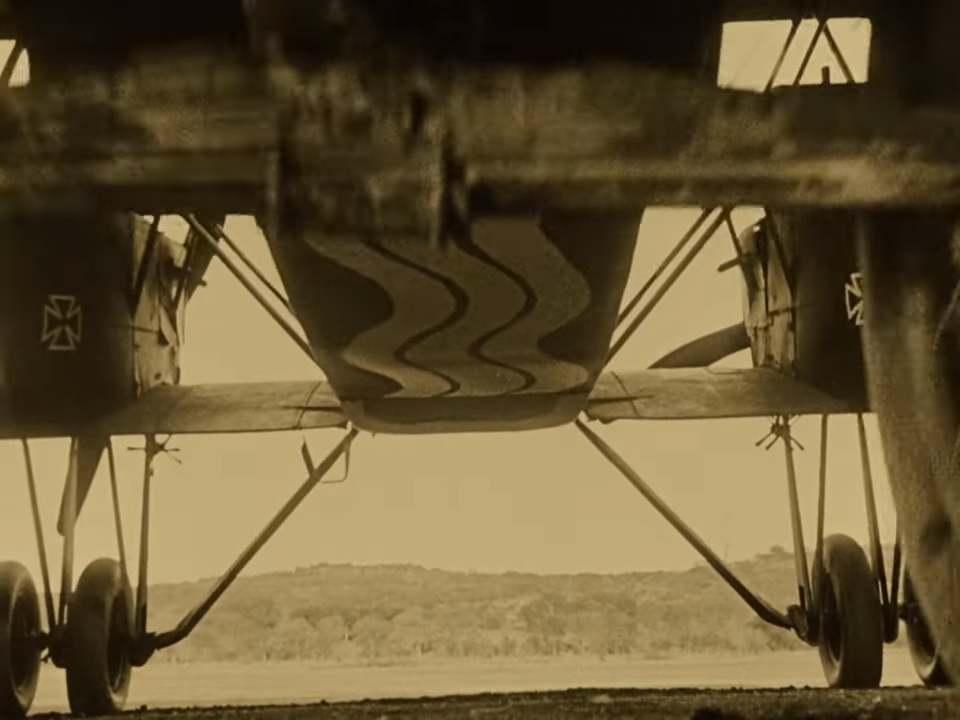

Even beyond these scenes, swings and parachutes become the vehicles through which Wellman vigorously moves his camera, while the arrival of the giant German plane Gotha brings with it a heavier, daunting presence. It quite literally rolls over us as it leaves the hangar, obstructing our low angle view with its wheels and struts, and even in the intertitles it is described as a “great dragon” which “roars out to seek its prey.” In this way, the action almost becomes fantastical, with such strong written imagery turning modern air combat into awe-inspiring folk tales. Our heroes who ride “eager birds” face this great evil head on, pouring “a stream of fire into the belly of the monster” while those on the ground below scurry around like ants.

One only needs to look at the exact same year in cinema history to see how technological innovation and cinematic panache don’t always line up, as 1927 saw The Jazz Singer introduce synchronised sound recording without a whole lot of artistry behind it. Here in Wings though, the two are inextricably linked, with Wellman putting his technician’s mind to work in the execution of daring set pieces that crash planes into each other mid-air, send deflated zeppelins to the ground in clouds of black smoke, and construct explosive spectacles out of widespread destruction.

Just as impressive is the fast-paced editing which cuts vigorously between multiple air duels at once, certainly taking inspiration from the Soviet montage movement, but also D.W. Griffith in the sharply coordinated intercutting between the air and ground. Such careful balancing of multiple narrative threads also brings a touch of dramatic irony to these scenes. When the Germans attack the town that Mary is working in as an ambulance driver, Jack does not realise that she is one of the victims down on the ground he is saving, nor is she immediately aware of his presence until she hears the name of the plane that rescued them – the ‘Shooting Star.’

Similarly, when David is forced to steal a German plane during the climactic battle of Saint-Mihiel, Jack remains tragically unaware that it is his own friend on the other end of his fire. Of course, this is also the first time David has mistakenly left behind his lucky charm, dooming him to the same fate as his old tentmate. Their companionship up to this point has not been without conflict, primarily stemming from David’s great efforts to protect his friend from heartbreak, and yet their final minutes together are spent in melancholy reconciliation. Though they both have their own romantic desires for women back home, it becomes evident that the greatest love in Wings is shared between these two men, who seal their affection here with cinema’s first same-sex kiss. In this moment, Wellman poignantly cuts to a plane sitting in front of a cemetery, its propellors slowing to a halt just as David passes away.

With silent movie stars like Clara Bow, Charles Rogers, and Richard Arlen leading this cast, Wings’ comic, dramatic, and action beats are injected with a whole lot of old Hollywood charm, grounding Wellman’s staggering practical effects in the hopeful idealism of youth. Those giant metal beasts which they fly through the air are monuments to their freedom, liberating them from the constraints of the ground, and yet such unruly, uninhibited ambition comes at a dangerous cost. With his soaring aerial photography and brisk editing, Wellman isn’t one to lose sight of such peril either, furiously beating back any preconceptions of silent cinema as being archaically stage-bound by turning its magnificent feats of engineering into vehicles for compelling, emotive storytelling.

Wings is in the public domain, and available to watch on many free video sharing sites including YouTube.