MaXXXine (2024)

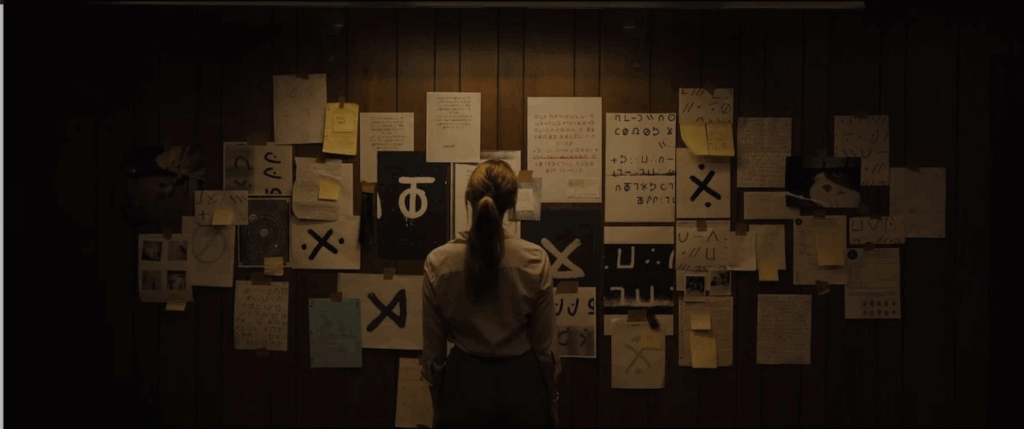

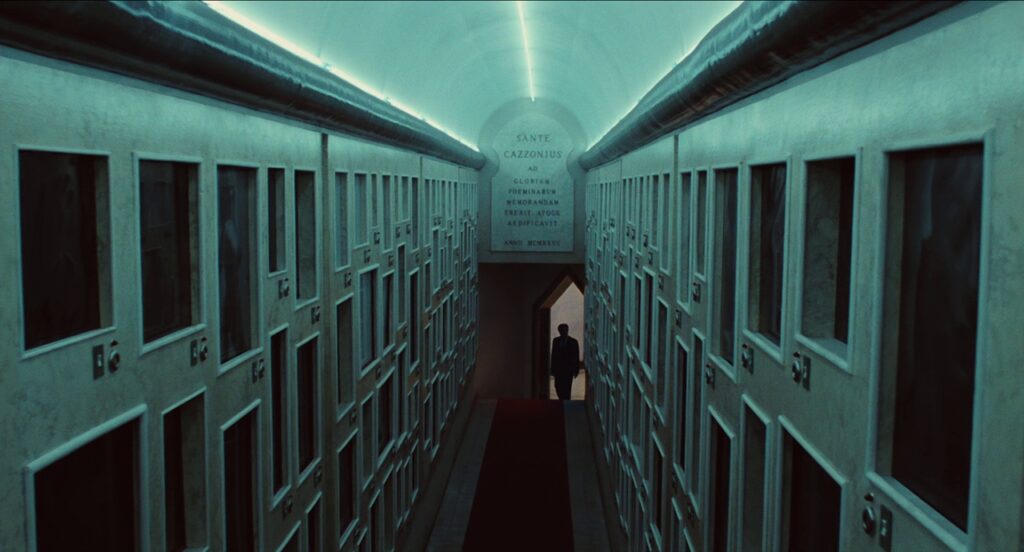

Ti West adeptly puts his own spin on the pulp, glamour, and splatter of 80s slasher movies in MaXXXine, satirically examining the cutthroat violence that underlies America’s celebrity culture, and ending his trilogic interrogation of the horror genre’s history with intoxicating, gaudy sensationalism.