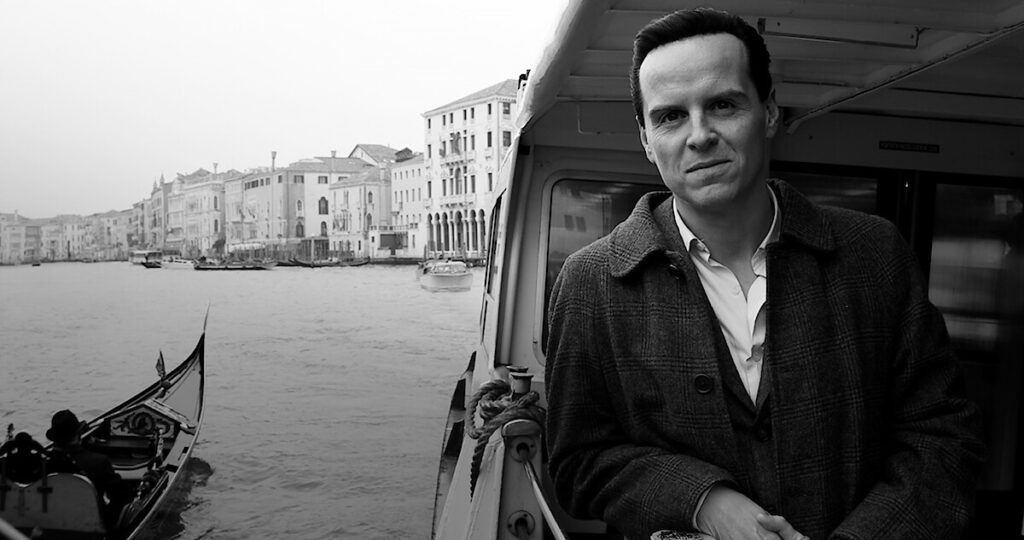

Ripley (2024)

The question of what exactly constitutes a fraud is meticulously woven throughout Steven Zaillian’s monochrome study of a New York con artist in Ripley, witnessing his unscrupulous attempts to ascend the social ladder by way of identity theft and murder, even as his own amoral corruption threatens to sink him into a dark, suffocating abyss.