Sergei Eisenstein | 1hr 15min

It is no coincidence that history’s most effective propaganda films have also featured fast-paced, avant-garde editing, and some of cinema’s finest at that. This device despicably valorised the Ku Klux Klan in The Birth of a Nation, celebrated Communist revolution in I Am Cuba, and stoked political conspiracy theories in Oliver Stone’s JFK – yet Battleship Potemkin nevertheless looms large among them all. The uprising of the working class against their Tsarist rulers is the central conflict here, and with Sergei Eisenstein labelling the oppressors “vampires” and “monsters,” it doesn’t take a great stretch of the imagination to realise where his loyalties lie.

This film is a product of the Soviet Union in its earliest years, not so much aiming to disseminate historical facts than to rouse passion and outrage from civilians. Under the purview of an artist who understands his craft on an intimate level though, Battleship Potemkin also transcends its own political message. The five methods of montage that Eisenstein developed in the early 1920s stand true across time, unaffected by shifting ideologies or opinions, and are cleanly distilled here in their purest forms. From this mechanical arrangement of moving images, he composes a narrative that disengages from conventional notions of heroic individualism, and in true socialist fashion identifies the collective masses as their own champions.

If we are to pick a protagonist from the vast ensemble gathered in Battleship Potemkin though, that label must fall on sailor Vakulinchuk, who leads his crew’s initial rebellion against the cruel commanding officers. Even then though, his presence after Act II is largely symbolic, spurring on the Bolshevik cause as a martyr. Besides the obvious political dramatisation, Eisenstein represents the story of the real Vakulinchuk relatively accurately here, using a little-known historical event as the foundation of his artistic experimentations.

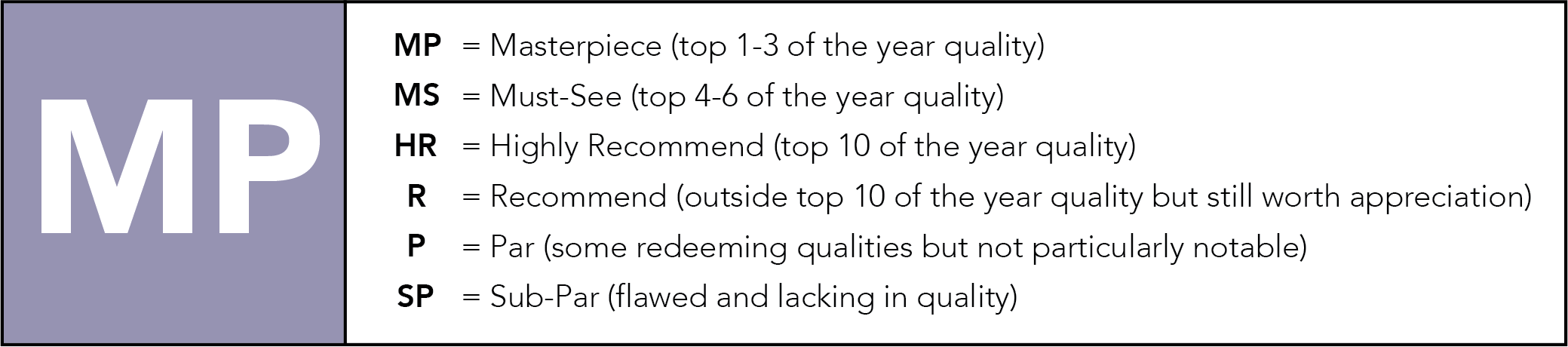

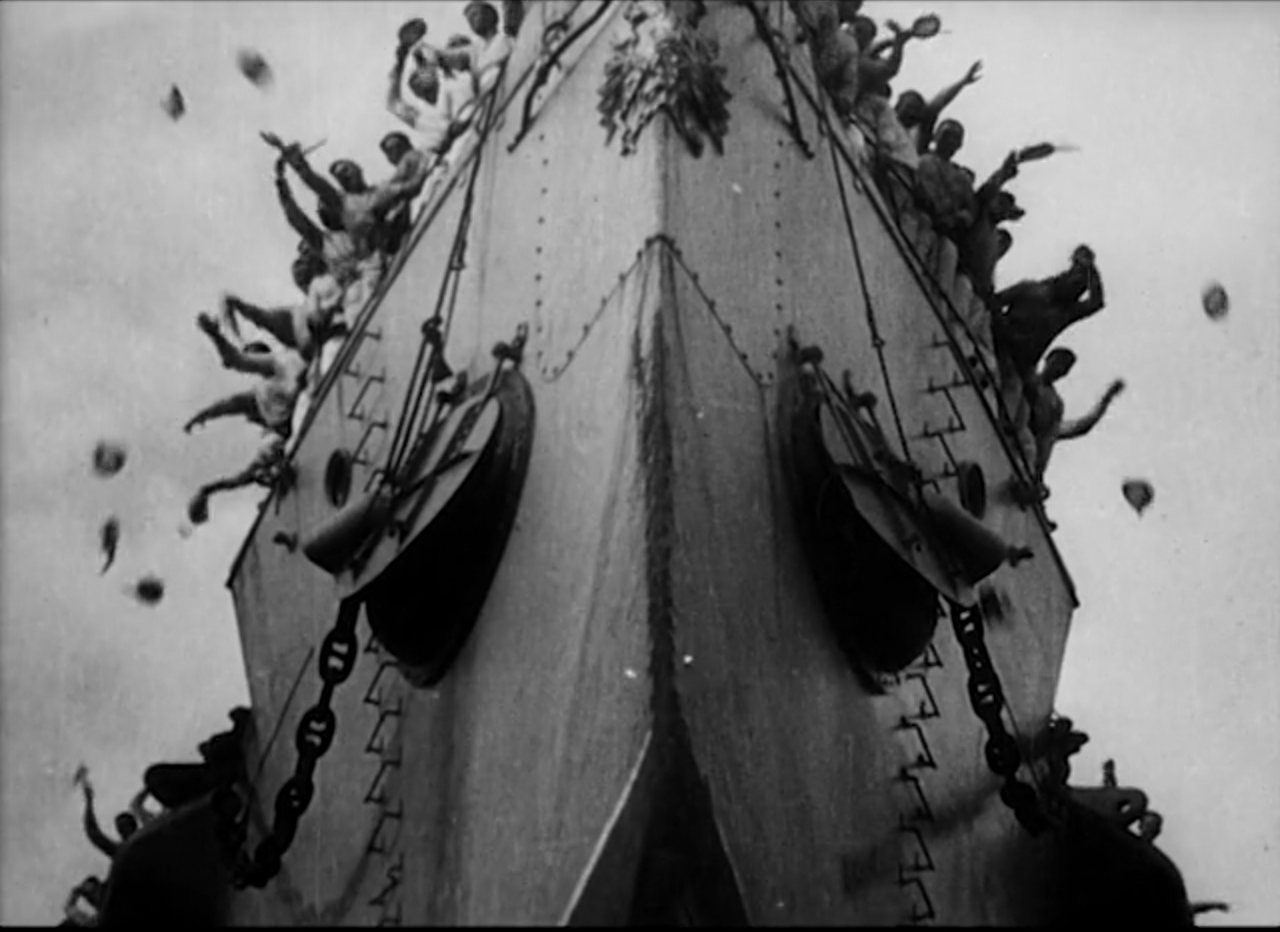

With Battleship Potemkin‘s dedication to packing hundreds of extras into the scenery and covering the full totality of this revolt, it may very well be one of the shortest epics ever put to screen, coming in well under 90 minutes. This can be mainly attributed to the sheer amount of visual information being thrown at us in the brisk, economical editing, though Eisenstein’s magnificent mise-en-scène shouldn’t be underrated either, particularly in scenes set upon that remarkable monument of naval warfare that is the Potemkin. Here, he carves out a rigorous array of geometric shapes from its industrial design, slicing through compositions with long, grey cannons and trapping its crew among vast webs of rope. Symmetry is crucial here as well, particularly in his blocking of the crew in militaristic formations along both sides of the deck, while his immense depth of field capture them in motion across multiple levels of the ship.

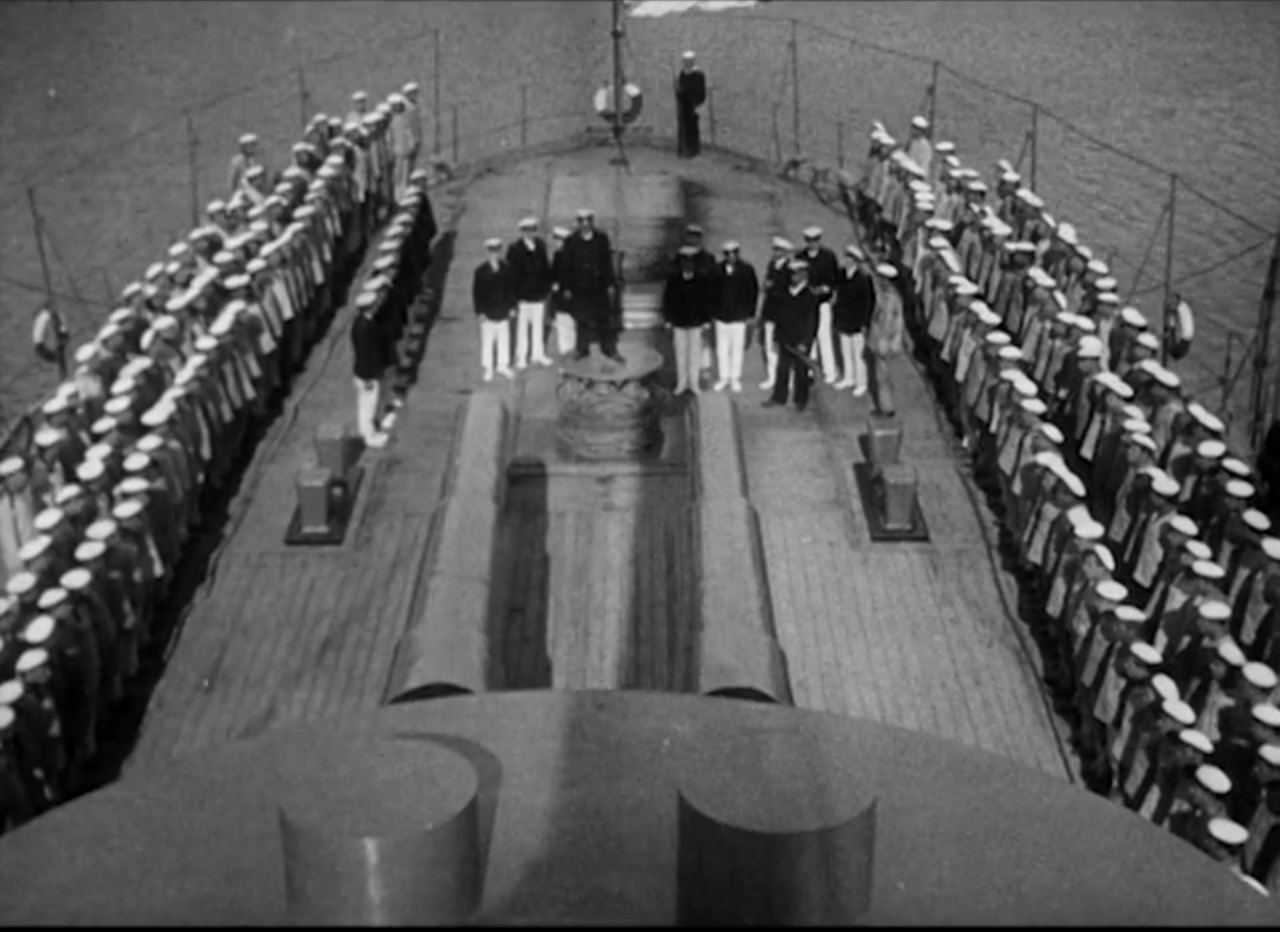

Inside the sleeping berth where Eisenstein’s story begins, the hammocks crowding the frame almost look like cocoons, hinting at the imminent emergence of newly born insurgents. Talk of revolution has been passing around for some time, and after they refuse to eat a hunk of rotten, maggot-infested meat, the threat of execution is visualised in a haunting dissolve of bodies hanging from the masts.

The rising tension here demonstrates the first of Eisenstein’s five methods, metric montage, which creates a tempo based on a specific number of frames for each shot. As a canvas cover is thrown over the condemned sailors and a firing squad marches out, the pacing accelerates, cutting between rifles raised in perfect rows, Vakulinchuk’s stirring fury, and the officers’ malicious grins. This immediate danger is what finally triggers the riot on the vessel, leading into the first of Battleship Potemkin’s bravura set pieces.

Eisenstein’s staging here is marvellous, navigating the multiple battles unfolding across the ship with rhythmic montage – the adjustment of each shot length according to the movement unfolding onscreen. Meanwhile, cutaways to the Russian Orthodox priest onboard reveal him holding his cross like a weapon, demonstrating intellectual montage through the symbolic association of juxtaposed shots. These sailors are not merely rebelling against the government or its armed forces, but are subverting organised religion itself, toppling the power structures which bolster the Tsarist rule.

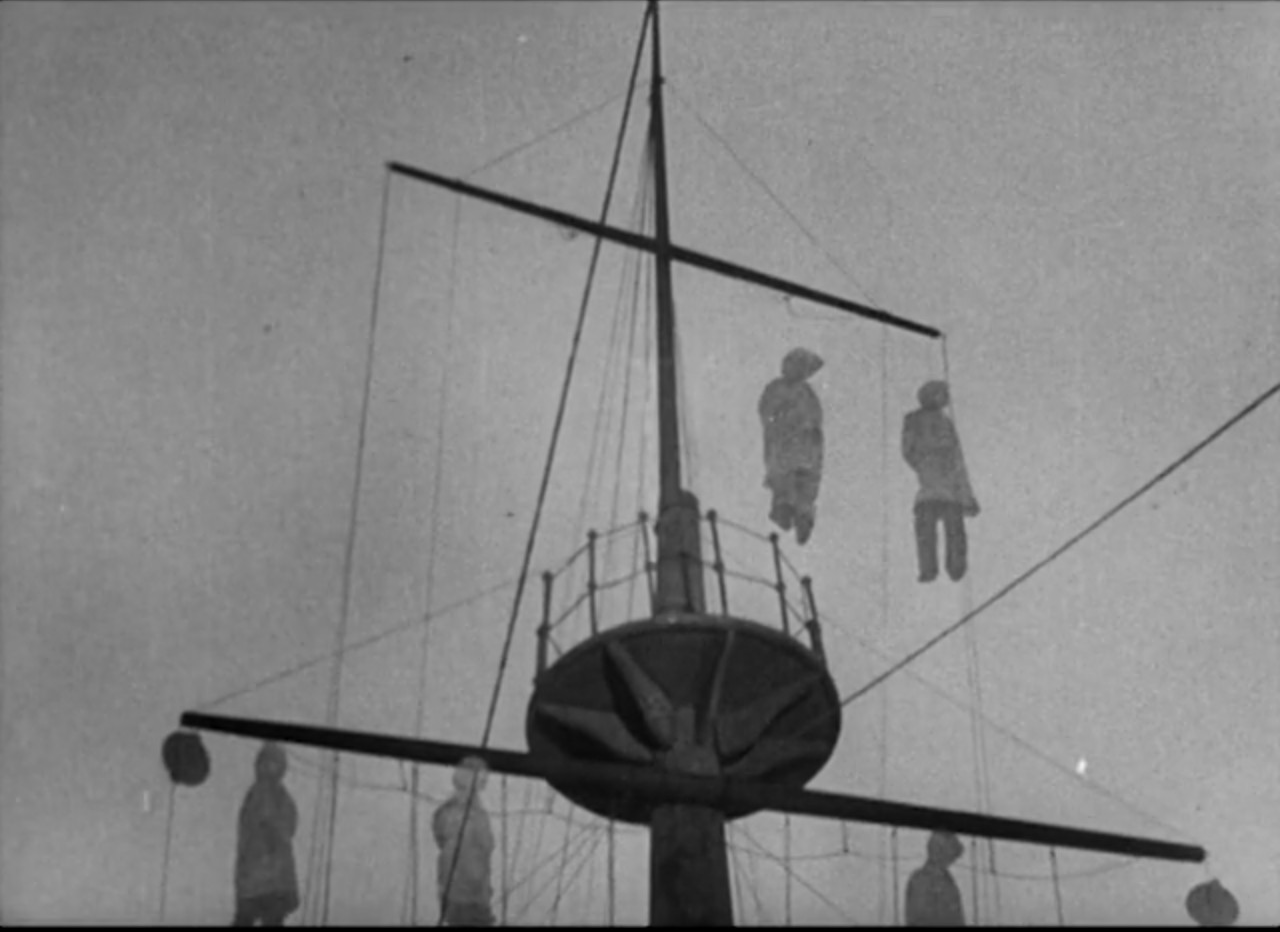

This mutiny is a victory for the Bolsheviks, yet for now celebrations must be put aside to mourn the loss of Valukinchuk, whose body is delivered to the Port of Odessa and set up inside makeshift shrine. Ships gently pass by as bereaved crowds gather, looking to pay respects in powerful solidarity. Eisenstein’s editing is not defined by tempo, continuity, or symbolism here, but rather uses complementary close-ups and long shots of unified crowds to capture the melancholy lament in the air, typifying his method of tonal montage. When one loudmouthed man tries to turn this wounded sorrow into antisemitic prejudice, fists clench and brows furrow, but not in support of his bigotry. Everyone can see that he is appropriating this tragedy for his own purposes, and thus he is promptly shut down.

As the Potemkin docks at the Port of Odessa and its locals gather in camaraderie, Eisenstein continues to navigate these swells of emotion with remarkable dexterity, even injecting colour in 108 frames of a waving red flag that he hand-tinted himself. As such, the shift from enamoured celebration to terror arrives with a jolt, heralded by a woman’s head violently spasming in uneven jump cuts as she is shot down by an advancing Cossack army. Before we can even register the threat, the infamous massacre upon the Odessa Steps has begun, seeing Eisenstein pull out every montage technique at his disposal to deliver seven minutes of raw editing genius.

From either end of this Soviet landmark, the stairway appears to stretch far into the distance, forcing citizens to flee towards either the infantry descending from above or the cavalry waiting to pick them off below. Eisenstein’s camera does not offer these soldiers the same empathetic close-ups as it does their victims, only ever taking their perspective by descending the steps with their steadfast regiment, and moving in a line as unyielding as the geometric formations of their raised rifles.

While this wall of white uniforms mows down everyone in their path, children are horrifically crushed in the stampede, pushing one devastated mother to pick up the broken body of her son and face her assailants. She stands alone in their long, dark shadows, begging them to end this terror, and for a brief moment we wonder whether she has at least slightly stirred their hearts. Within this fable of good and evil though, Eisenstein leaves no room for moral ambiguity – this mother is shot dead on the spot, and the Cossacks continue their forward march.

As the Odessa Steps sequence torpedos towards its climax, Eisenstein demonstrates the fifth type of montage that he defined as a young film theorist, inducing a more complex emotional response than metric, rhythmic, or tonal montages on their own. Overtonal montage combines all three here, suspensefully inching a baby carriage closer to the steps, following the motion of its uncontrolled descent, and spreading panic among onlookers who helplessly watch on in terror. The pacing accelerates as we cut from the baby’s face to the spinning wheels, and then just as it tips over, we are confronted by a snarling Cossack soldier striking the camera. Denying us the clean resolution of a long shot, Eisenstein instead chooses to end this sequence on a dissonant note, tightly framing a gasping woman with shattered, blood-streaked spectacles before fading to black.

More than any political message or isolated image, Eisenstein recognises that emotion in film is derived from the timing and arrangement of these shots, congealing into a sweeping indictment of the merciless Tsarist regime. Beyond the disenfranchised men leading the Bolshevik cause, the innocence of women and children are at stake in Battleship Potemkin, and with it, the lifeblood of the very nation.

If the government considers this slaughter the best course of action to quell growing dissent among civilians, then they underestimate the furious passion of the Bolsheviks. “The ship’s guns roared into reply to the massacre,” the intertitles read, before we witness the Potemkin’s cannons shatter the Odessa Opera House into pieces.

That night as its sailors rest and prepare for an imminent confrontation with the Tsarist squadrons, Eisenstein settles an anxious tranquillity across the ship, silhouetting men against moonlit skies and slowing his montage editing down to a gentle lull. When that fleet of enemy ships begins to emerge over the horizon though, Battleship Potemkin launches into its final set piece, fearfully anticipating the gunfire that will surely sink this vessel of hope.

Machines whir and black smoke billows from the warship’s chimneys, hanging a dark, ominous cloud overhead as it steers towards the squadron with nothing but a tiny destroyer by its side. Rather than meeting them with violence though, another far riskier tactic is considered. “Signal them to join us!” the sailors call out, raising flags and beseeching peaceful passage.

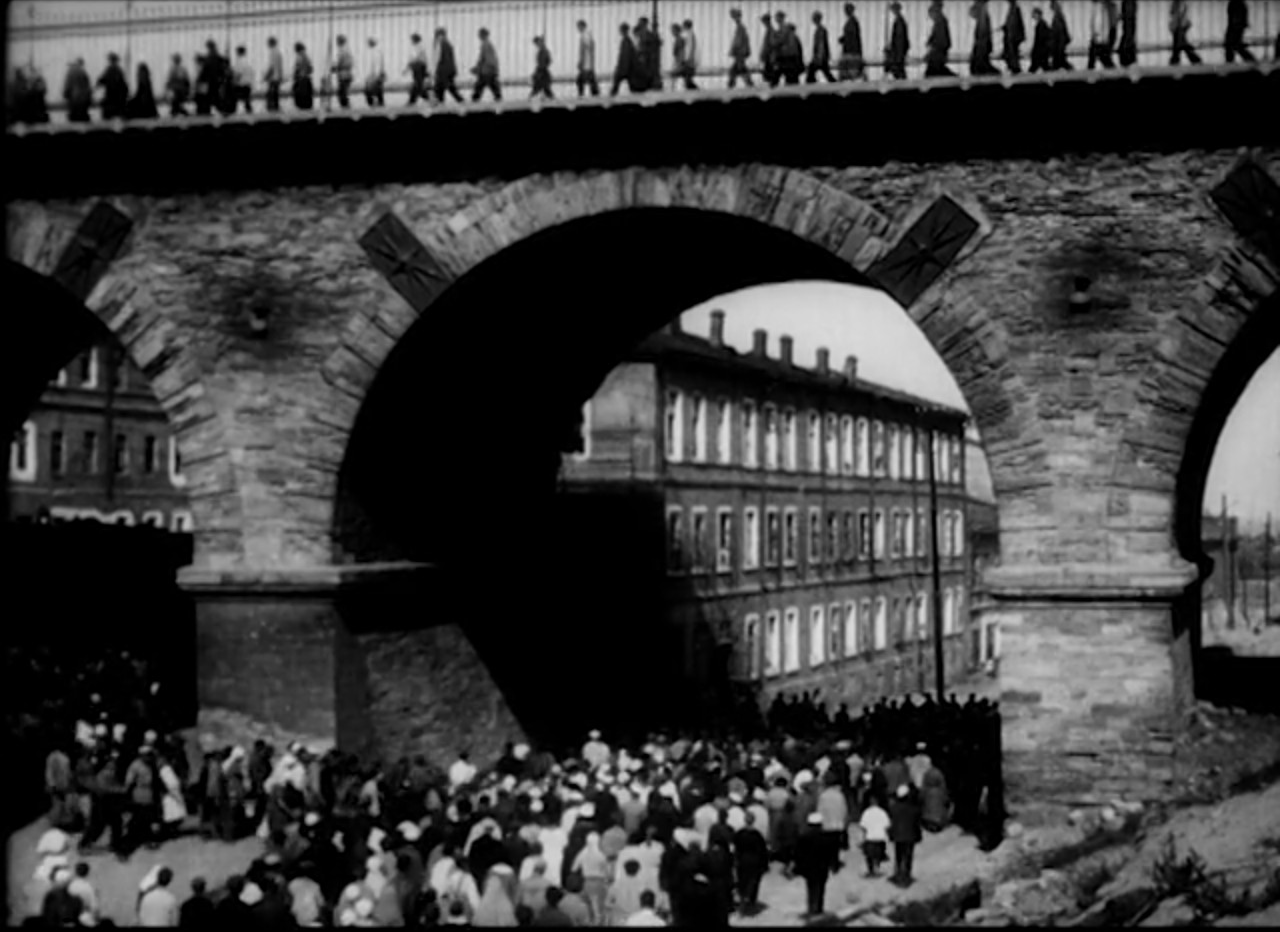

Once again, Eisenstein uses his metric montage to drive up tension, weaving close-ups of rotating gun turrets and rising cannon muzzles among long shots of the naval battleground – though this time bloodshed does not eventuate. “Brothers!” the sailors of the Potemkin call to their comrades aboard the Tsarist fleet, who eagerly allow them to pass between their ships. Hanging from the railings and crow’s nests, crews from both sides wave to each in solidarity, spurring on the Bolshevik movement which in years to come will take over all of Russia.

Such bright optimism marks a notable shift from the bleak cynicism which ended Eisenstein’s previous film Strike, though if anything it simply proves the versatility of his editorial orchestrations, coordinating hundreds of dynamic images into fervent expressions that span humanity’s full emotional spectrum. In the hands of this young Soviet film theorist, cinema becomes a symphony of notes, rhythms, and textures, and Battleship Potemkin towers within the art form as the peak of such visual, kinetic innovation.

Battleship Potemkin is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Didn’t realize Strike and Battleship Potemkin came in the same year 1925

Yep it was a big year for Eisenstein.