Ken Russell | 1hr 51min

The French Wars of Religion had long since passed by the time the fortified town of Loudon became the epicentre of lingering tension between Catholics and Protestants in the 17th century, setting the scene in The Devils for a battle fought not with weapons, but political and religious manipulation. Urbain Grandier, the outspoken priest charged with defending the statehood of Loudon, is popular among the people for standing firmly with its high Protestant population, while making enemies of those Catholic authorities who deem him a threat. If Loudon is to be demolished and subjected to the rule of the Catholic Church though, then it would take more than an assassination to undermine Grandier’s influence. The priest must be so thoroughly discredited to the point of humiliation that no one can stand by his side without suffering the same ostracisation, thus bringing the rest of the town to its knees in feeble surrender.

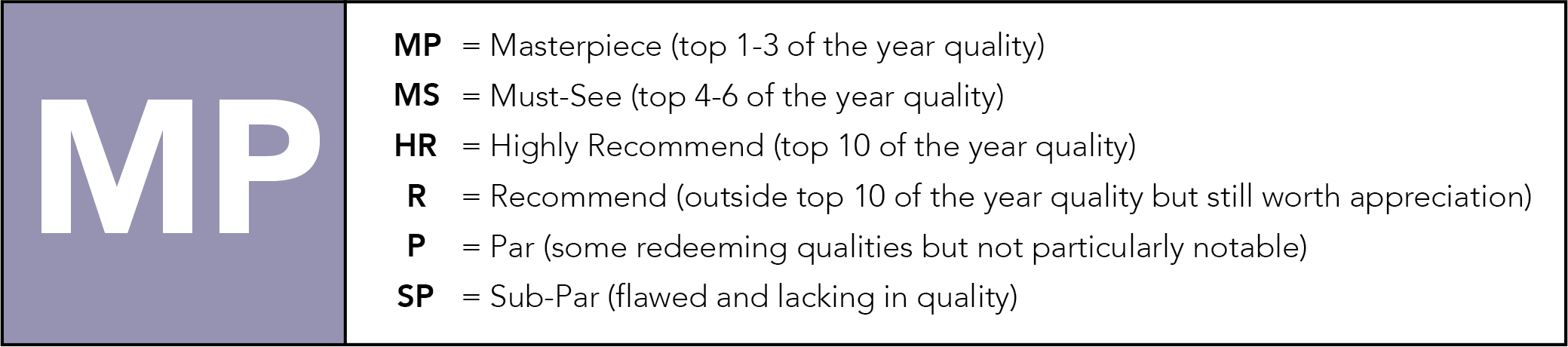

It is incredibly good timing then that Sister Jeanne des Anges should come forward with baseless accusations of witchcraft aimed squarely at Grandier right as the Church begins conspiring against him. Though she is the abbess of the local Ursuline convent in Loudon, she is an outsider among her own nuns, tormented by sexual desire for Grandier and filled with self-loathing over her hunchback. “Take away my hump!” she prays in screaming agony, longing to be seen for once as beautiful. As such, when she discovers that Grandier has married another local woman, her furious, vindictive jealousy is unleashed.

Ken Russell’s narrative and characters here are rooted heavily in recorded history, yet the parallels shared between The Devils and Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible are extremely visible. Both storytellers are heavily concerned with humanity’s natural tendency towards irrational fear, and how it drove the discrimination against individuals in a pair of 17th century settings. Where Miller sought to write an allegory for 1950s McCarthyism by studying the infectious hysteria of the Salem witch trials though, Russell feverishly opposes 1970s religious conservatism in The Devils, treading far more explicit ground with violence and nudity that triggered the censors to come down hard with an X rating.

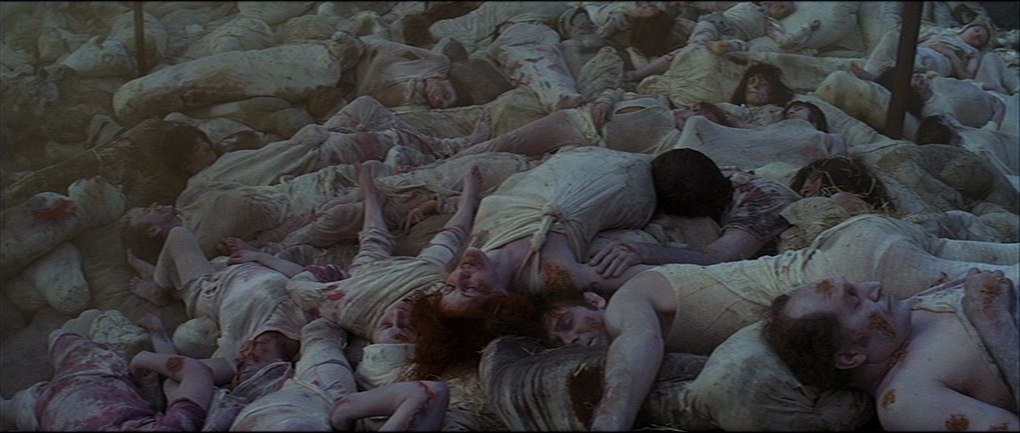

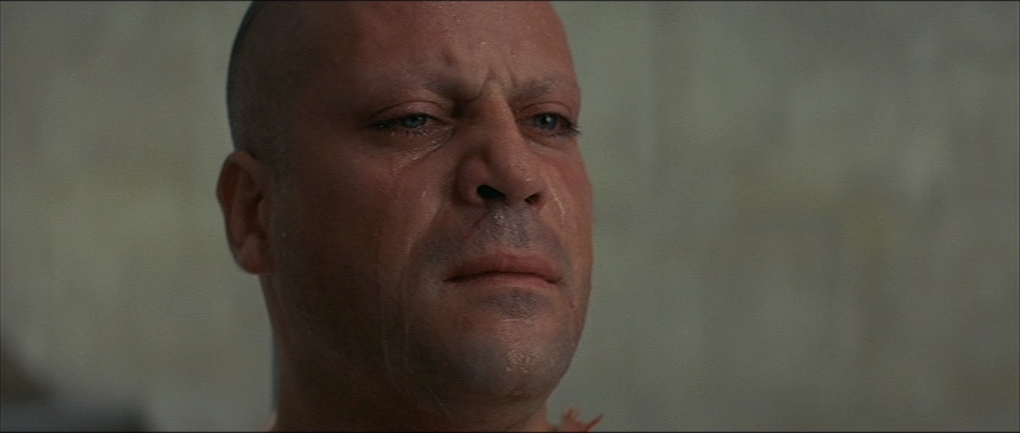

From Russell’s perspective though, the outrage that surrounded The Devils would have been far more justified had it been directed at the harsh subject matter it is depicting. He particularly expressed frustration over the deletion of the scene he called the “Rape of Christ,” in which Sister Jeanne masturbates using the charred femur of the deceased Grandier following his execution. Even without this though, Christianity’s perversion of its own spiritual icons rings loudly throughout The Devils, framing Grandier as a persecuted saviour being punished for the sins of the world. Vanessa Redgrave may steal every one of her scenes with Sister Jeanne’s hunched posture and seething contempt, but Oliver Reed’s commanding presence is a steady, unwavering force among Russell’s visual chaos, taking to the screen with the booming confidence of a seasoned theatre actor. As he is cruelly interrogated by the Church, he delivers monologues with resounding gravitas, shamefully confessing his flaws as a prideful, even lecherous man while meeting Sister Jeanne’s accusations of sneaking into her bed with righteous indignation.

“Call me vain and proud, the greatest sinner to ever walk in God’s Earth! But Satan’s boy I could never be! I haven’t the humility. I know what I have done, and I am prepared for what I shall reap. But do you, Reverend Mother, know what you must give to have your wish about me fulfilled? I will tell you. Your immortal soul to eternal damnation. May God have mercy on you.”

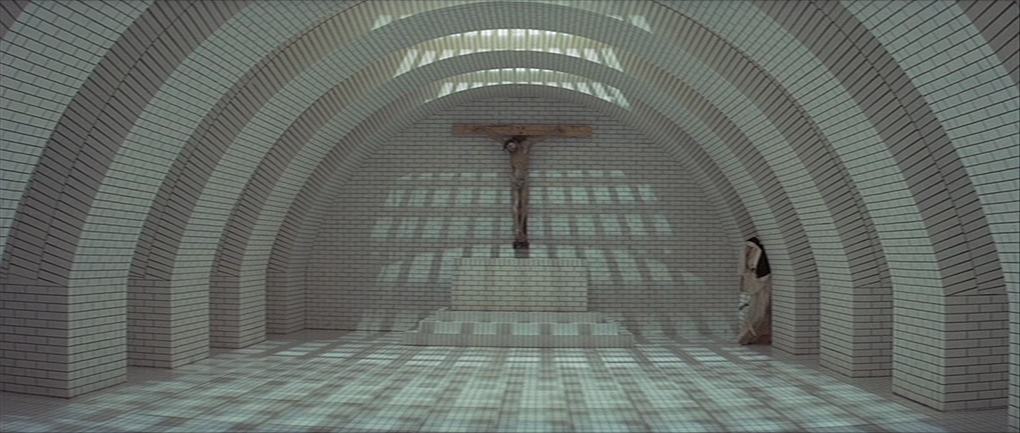

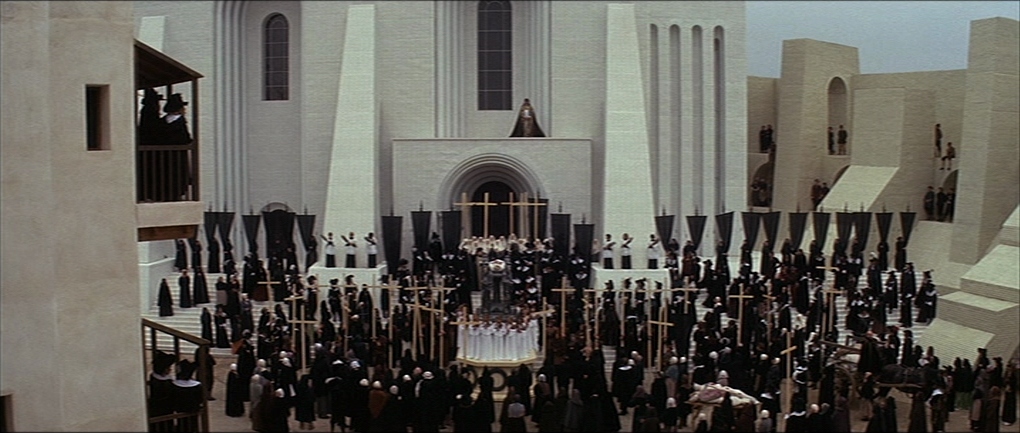

Grandier is far from sinless, but what man living at this time of religious corruption and violence isn’t? In their monochrome garments, Russell’s characters often blend in seamlessly with the clean white masonry and darkened rooms of Loudon, becoming one with the dominant palette that tangibly manifests their harsh moral binaries. The town of perfectly rounded arches and geometric skyline makes for a remarkable feat of production design too, combining the stark minimalism of The Passion of Joan of Arc with the architectural ambition of Metropolis, and formally drawing this austerity through rigorously blocked scenes of black-and-white crowds.

It is no coincidence that the one figure who doesn’t conform to Russell’s sparse visual design is the puppeteer of Loudon’s witch hunt, sitting high above the fray. Dressed in his blood-red robes and wheeled around by servants, Cardinal Richelieu appears to be the only true demon in this town’s vicinity, determined to destroy the man who stands between him and the demolition of Loudon’s walls. Where Sister Jeanne acts impulsively on a wounded ego and even attempts to hang herself late in the film, Richelieu carefully orchestrates Loudon’s descent into madness, chaotically underscored by a writhing, discordant cacophony of pipe organs, trumpets, and percussion. In this period setting, the anachronistic jazz of Peter Maxwell Davies does not seem so unholy as it does viciously anarchic, matching confronting scenes of nuns playing up their fake possession with an equally disturbing soundscape.

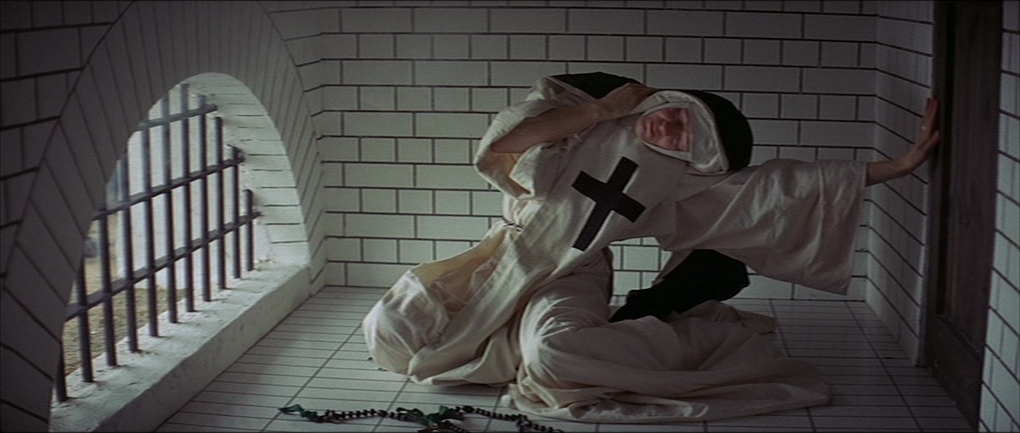

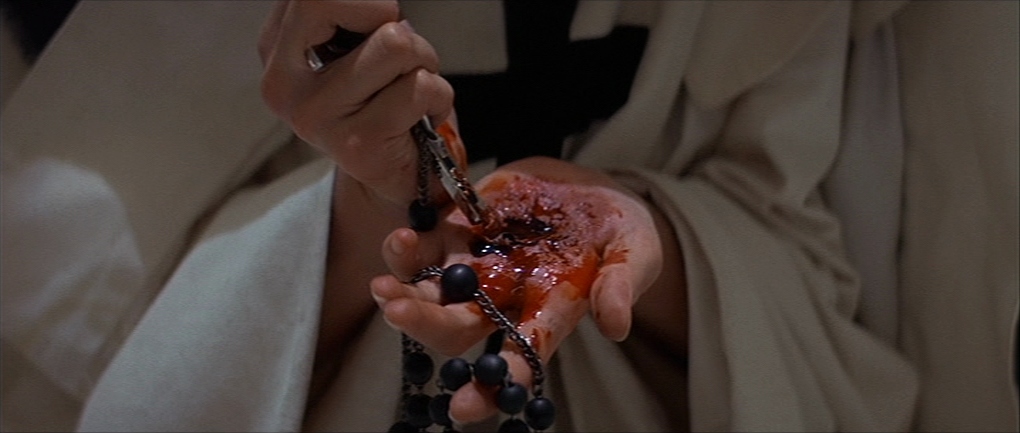

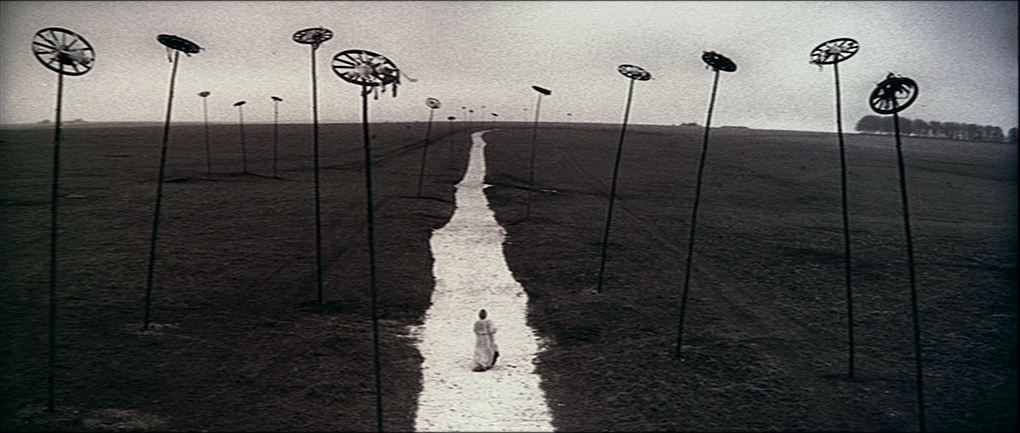

Only when Grandier has perished through fiery injustice at the stake does silence settle over the town again, albeit one that is despairingly lifeless. His refusal to confess to the false charges may be the only solace to be taken from this, as it is with his last breath that the walls of Loudon come crumbling down in chilling synchronicity, ushering in apocalyptic scenes of ruin and suffering. Right to the final frame, Russell’s theological symbolism continues to inform his magnificent visuals and narrative, as his camera sits on a long shot of Grandier’s wife Madeleine approach an opening in the town’s demolished fortifications.

No longer drawing a clean divide between its shades of black and white, The Devils’ bleak scenery sinks into a dirty greyscale, as the widow trudges over a mountain of debris and exits what was once a vice-ridden yet relatively sheltered Garden of Eden. No longer do the strings and woodwinds clash in fervent rhythms, yet still they whine and wander through dissonant harmonies as Madeleine shuffles forward into an uncertain future. The Devils may be set in 17th century France, and yet with his final note Russell’s mourning of what religious tyranny has destroyed continues to escape a narrow relegation to the distant past, infusing his cautionary tale with a bitter, anachronistic timelessness.

The Devils is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

What are other Oliver Reed films/performances you would recommend?

It’s very much a supporting role, but he is great as Vulcan in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. I haven’t seen Oliver yet but I’m interested to see him as Bill Sykes there too.

I thought he was quite good in Nic Roeg’s Castaway…