Roman Polanski | 1hr 41min

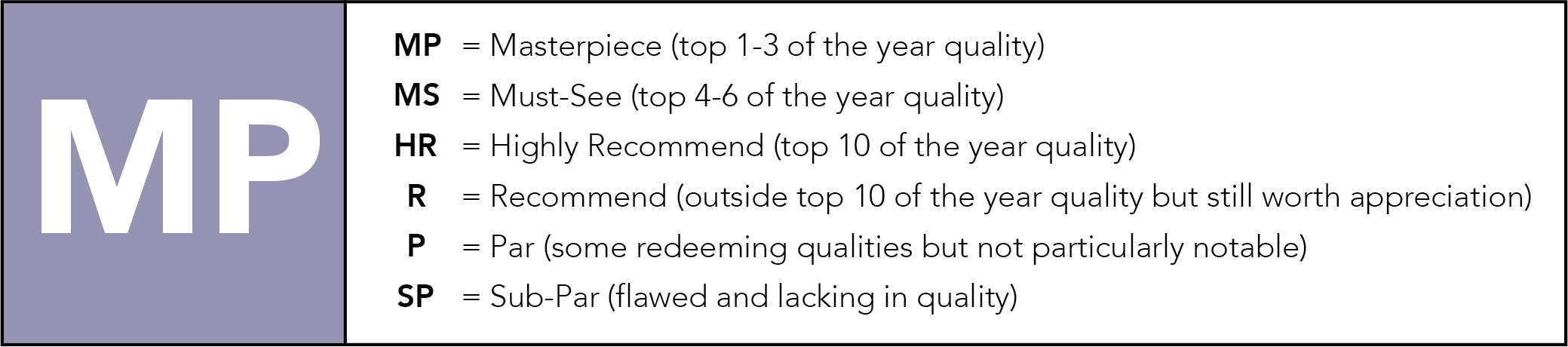

The moment that the mysterious, unnamed hitchhiker of Knife in the Water boards the yacht of upper-class couple Andrzej and Krystyna, Roman Polanski’s camera attaches to the switchblade he carries in his pocket. It proves its utility as a practical tool, cutting ropes when the boat ends up marooned in shallow water, and slicing up food during meals. The dangerous game the hitchhiker plays of Five Finger Fillet is surely an impressive feat of dexterity too, and although Andrzej puts an end to it with apparent concerns of ruining the deck, his competitive side soon emerges when they take turns throwing it at the wall. Going by the lingering close-ups that Polanski uses to suspensefully track the knife’s movement, it would be safe to assume that this is his Chekhov’s gun, and it indeed serves an integral role at the climax. Ultimately though, the symbolic weight that is placed in this phallic icon of masculinity far outweighs its physical danger, chillingly sinking a rocky marriage before it gets the chance to take a life.

Although the hitchhiker is spontaneously invited along as a plaything for the wealthy couple, the insecurity he sparks in Andrzej transcends class boundaries, both being men vying for the attention of Krystyna. Adding to the tension as well is the suggestion that Krystyna herself may not necessarily belong in this upper stratosphere of society, having married into money rather than being born into it. The egotism of her rich husband is as plainly evident to her as the hitchhiker’s jealous desire to become him, constantly drawing them into contest over that all-important knife.

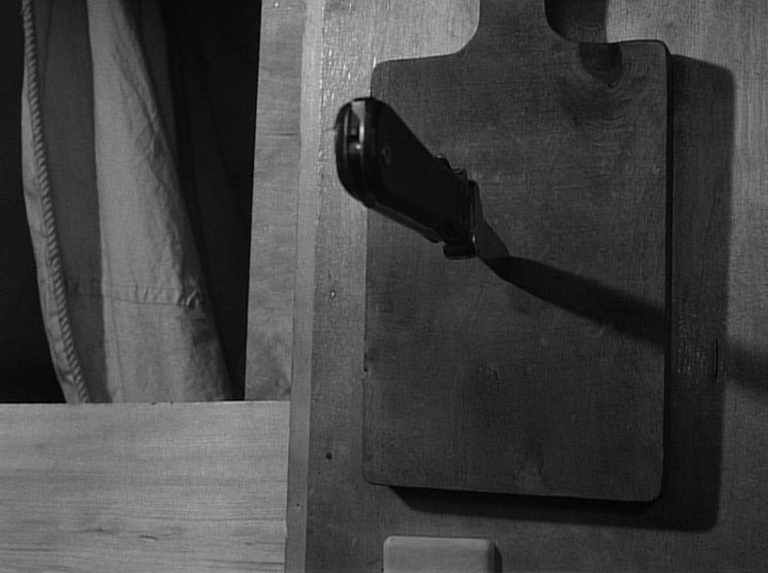

The only evidence that might hint at Knife in the Water being Polanski’s directorial debut is the clearly limited budget that confines much of his narrative to the yacht, though there are few single-location films as visually inventive and resourceful as this. No doubt this is in part due to his keen study of cinema’s greats, with his manipulation of suspense through tracking shots and editing bearing the mark of Alfred Hitchcock, and the incredible depth of field across extreme camera angles pointing to Orson Welles. Even the shrewd framing of multiple faces in close-ups delivers a hypothetical answer to the question of what a psychological thriller might look like if it were directed by Ingmar Bergman, and was grounded in social critique rather than existential horror. Quite remarkably though, Polanski’s visuals do not merely dwell in the shadow of his influences, but are given a new, distinctive shape that sits alongside some of their finest works.

The yacht itself is a fascinatingly geometric set piece bound by ropes, poles, and sails, and yet Polanski prefers using his actors’ bodies as obstructions and frames in the mise-en-scène. Legs, heads, and arms are often isolated in the foreground, reflecting their fluctuating power dynamics as they take turns dominating the scenery, and disconnecting the characters from each other. Polanski intimately presses us against their bare skin from low camera positions, while high angles alternately lay their vulnerable, half-dressed bodies out on the deck, like sacrifices prepared on an altar. Being surrounded by open water, they are obviously not trapped in any physical confines, and yet within Polanski’s claustrophobic blocking they are all victims of a parasitic social environment that they have created for themselves.

After all, each passenger has something to selfishly gain from the others in this allegory of class and gender, letting us carefully scrutinise the complex web of desire and contempt that lies between them. When Andrzej first notices the hitchhiker on the road, he decides to teach him a lesson by swerving dangerously close to where he is standing, and when he invites the young man onboard, he wields his position of boat captain with smarmy authority. It is all a game to him, until he notices his dominance being undermined by the hitchhiker’s mocking jabs, minor rebellions, and flirty pursuit of Krystyna, who alternates in the middle between amusement and apprehension.

Along with his nerve-wracking knife motif, Polanski skilfully uses these interactions to formally lay the groundwork of their eventual reckoning. The hitchhiker’s inability to swim is ominously underscored as a key plot point, while the fact that Andrzej has named his boat after his wife subtly marks them equally as his property, turning any competition for one into a contest for both. Andrzej fully realises the masculine power that resides in the hitchhiker’s switchblade when he steals it for himself, making a potentially deadly struggle all but inevitable when tensions eventually boil over and send his guest overboard. With no sign of him resurfacing, Andrzej immediately assumes the worst, briefly considering covering the tracks of his apparent murder before resolving to swim to shore and fetch police. As a result, a window of opportunity finally opens to the surviving hitchhiker who has secretly clung to a nearby buoy. With Andrzej out of the picture, he reboards the yacht, sleeps with Krystyna, and thus takes the rich man’s wife and boat as his own.

Even after the boat is returned to shore and Krystyna is reunited with her husband, Polanski’s social critique doesn’t lose its savage edge. With Andrzej’s image of masculine and financial power complete damaged in his wife’s eyes, his insecurity as a weak, jealous man has also been exposed, desperately reducing women and lower-class citizens to toys so that he may wield a flimsy control over them. There is nothing left for him to say as they drive back home, nor any way he can mend the brittle foundations of this relationship. At a road intersection, he brings the car to a complete standstill, as reluctant to continue forward as he is scared to move back. Murder would be far too clean a resolution to Knife in the Water’s thrilling acute interrogation of class and marital breakdown. By the time Polanski has stripped away all pretensions of dignity in his ensemble, so too have they lost their ability to confront complex situations with decisive action, and revealed the critical emptiness of their moral character.

Knife in the Water is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the Blu-ray is available to purchase on Amazon.

You have interpreted the ending wrong. It is ambiguous. The crossroad is a decision making point that we do not see on screen. One road leads to the Police station. The other to their home. He didn’t stop the car because he was reluctant to continue forward or scared to move back. The episode with the hitchhiker is over. He isn’t trying to find the hitchhiker again or try to murder him.

Thanks, I’ll have to give it another watch.

I also wanted to add even though it is a small production it was a very tough and technical shoot. The technique to shoot people inside the car with the car going forward was not yet available. So to achieve this the car had to be driven by only seeing the trees/environment sideways while the crew was taking the shot from the front.

Also a very expensive camera was lost while taking an overhead shot from the boat.

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green