Federico Fellini | 1hr 58min

Every evening on the same Roman street, Giuletta Masina’s lonely prostitute passes time with her fellow ladies of the night, and waits to be picked up by men. Her birth name is Maria, but at some point between being orphaned as a young girl and taking on her current profession, Cabiria became the moniker which her friends and clients came to know her by. Elsewhere in the same city, a shrine to the Madonna draws believers from far and wide who desperately throw themselves on the ground and beg for their prayers to be heard. “Viva Maria!” they zealously cry out, and as Cabiria awkwardly joins the multitude to plead for a better life, Federico Fellini draws a striking parallel between the two women.

Here he presents a virgin and a prostitute – both named Maria, both drawn to God, and both embodying intrinsic goodness. In a symbolic rendering of the Madonna-whore complex though, the name that is shouted in passionate ardour through the churches of Rome refers only to one of them. Men have their fun with Cabiria for a time, but too often they discard her just as easily as they pick her up, cruelly twisting the knife on their way out. She is treated with all the dignity of a used rag, while the Virgin Mary continues garnering respect thousands of years after her death.

Of course, the modern-day Rome of Nights of Cabiria would never accept this irony. Fellini’s love of the city’s history and culture is only outdone by his disgust at its hypocrisy, and six films deep into his directorial career, that cynicism is only increasing as he watches it destroy icons of innocence. Though the narrative is far more straightforward than his later films, it is still very much a character piece, relying heavily on Masina’s extraordinary ability to command our awe and empathy as the tragically forsaken Cabiria.

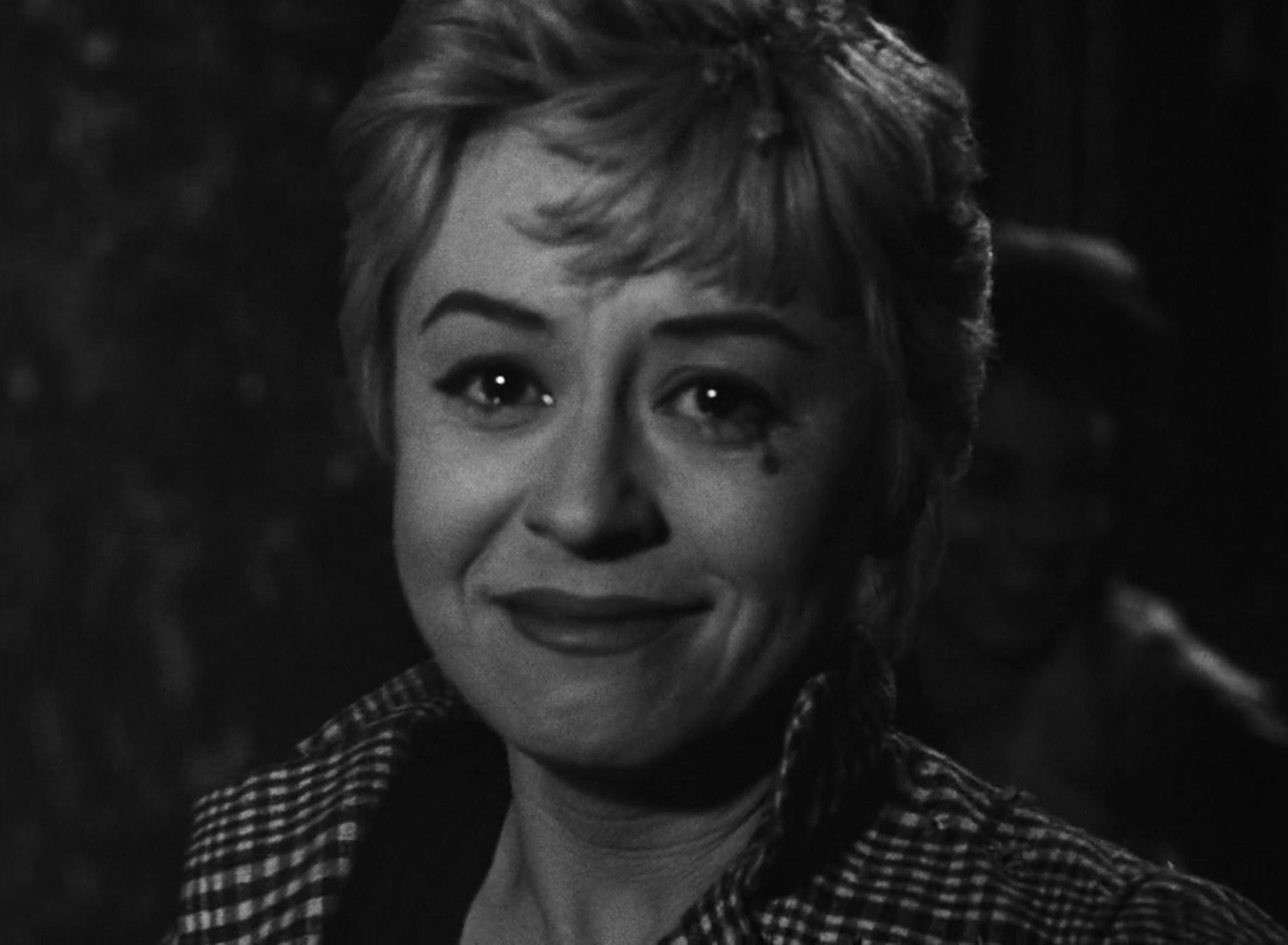

As always, Masina’s large, expressive eyes and dark eyebrows constantly project longing, joy, and anguish, though Cabiria is also far more world-weary than many of her previous characters. Where Gelsomina’s shattered innocence in La Strada leads to a tragic downfall, Cabiria wears her pessimism like a protective shell, even as she quietly searches for reasons to let some shred of hope through. Her high heels do little to lift her tiny stature as she shrinks beneath both men and women, but thanks to her feisty spirit that isn’t afraid to back down from petty fights, she rarely fades into any crowd.

As Cabiria is so often written off as simple-minded and cheap by those looking for an easy laugh, any instance where she is lifted off her street corner by a man and placed on a pedestal becomes a moment of ecstasy, and each time she fully believes that she has found acceptance within the society she both loathes and adores. So often does this happen in Nights of Cabiria that it virtually becomes part of its narrative structure, convincing her each time that this relationship will be the one to lift her out of poverty, only to deflate the fantasy the moment something more enticing catches their eye.

In the film’s very first scene, it is Cabiria’s boyfriend Giorgio who steals her purse and pushes her into a river, while later movie star Alberto Lazzari takes her home on a whim simply because she is the first woman he sees after breaking up with his girlfriend. His vast, lavish villa makes for a jarring visual contrast against the seedy neon signs and worn architecture of downtown Rome, and especially the city’s barren outskirts where she resides in a small hovel. Fellini indulges in the symmetry of its grand stairway, opulent mirrors, and exotic artwork, giving her a glimpse of luxury before Alberto’s woman comes home begging for forgiveness and she is forced to hide in the bathroom for the night. The scene would almost belong in a screwball comedy if it wasn’t so demeaning, revealing just how expendable Cabiria is compared to wealthier, more ‘respectable’ women.

Besides this brief but extravagant detour, Fellini’s location shooting out on the streets of Rome firmly entrench Nights of Cabiria in the harsh realities of the working class and their tedious routines. His deep focus lenses allow for some magnificently staged compositions of prostitutes loitering around cars and curbs, while the occasional addition of black umbrellas to these shots underscores the cold, wet discomfort of their lifestyles.

Living in environments as inhospitable as these, it is no wonder Cabiria is so awed by acts of altruism, even being stirred to seek mercy at the aforementioned shrine of the Madonna after observing one mysterious stranger feeding the homeless just outside the city. Much like the men in her life though, religion simply turns out to be another disappointment, leaving her and all the other hapless worshippers she prays with in the same destitute position as before. Maybe she just didn’t ask properly, one priest unhelpfully suggests, but she believes the problem goes deeper than that – she is simply too small and insignificant to live in God’s grace.

On the other hand, there is not exactly any sanctuary to be found in Satan’s seductive allure either, taking the symbolic form of a magic show run by a devil-horned hypnotist. As she stands onstage under his spell, Fellini fades the background into darkness, leaving only her face illuminated by a single spotlight beckoning from the void. For the first time, her peaceful, dreamy expression is wiped completely of any doubt, being entirely absorbed in the perfect world the magician has built for her. To the amusement of the audience, she dances a waltz through a garden with an imaginary man called Oscar, and inadvertently reveals her most personal fantasies for the world to laugh at.

Cabiria’s humiliation at being turned into cheap entertainment might almost be the end of her were it not for the near-mystical manifestation of the man from her dream, astoundingly also called Oscar. Fellini has firmly established his narrative’s pattern of broken and mended hearts by this point, so we are aligned in Cabiria’s initial suspicion around this seemingly perfect man, but she can only keep her naïve idealism at bay for so long before falling in deep love all over again. It isn’t long before she is accepting a marriage proposal and selling her small house to move far away, partly realising how naïve she is being, and yet nevertheless committing enthusiastically to her dream of new beginnings.

Upon a clifftop, Cabiria and Oscar’s silhouetted figures look out at the sun setting over a peaceful lake, and a happy ending finally seems within reach – but Fellini is no writer of fairy tales. This magical backdrop is undeserving of the brutal narrative pay-off that taints its scenery, formally mirroring the film’s first scene as Cabiria once again faces the threat of being robbed and thrown into the water. The mercy that Oscar takes on her is not out of love, but rather sheer pity as she willingly hands over her purse and begs to be killed, her heart unable to sustain any more pain.

Still, even at Cabiria’s lowest and Fellini’s most cynical, the rekindling of hope need not be some naïve submission to the same cycle of suffering that has perpetuated throughout Nights of Cabiria. After several hours laying and sobbing on the cliff edge, the pieces of a broken woman pick themselves up again, and she dejectedly continues down a nearby road. Very gradually, the sound of Italian folk music fills the air, and she is surrounded by musicians rapturously playing and dancing alongside her. For once she is part of a crowd that is not only acknowledging her, but delighted to have her present. A single tear forms in the corner of her left eye, black with mascara, and as she looks directly at the camera in the final seconds, we find an unfamiliar self-acceptance in her tender smile. This is not the end of Cabiria’s tragedies, though for as long as she holds onto the hope that keeps her alive, neither will it be the end of her profound joy.

Nights of Cabiria is currently streaming on Kanopy, and the Blu-ray is available to purchase on Amazon.

Have you seen Juliet of the Spirits yet?

If yes what’s your verdict of it. I think it’s a monumental Masterpiece. Belongs seat at the table with 8 1/2. It’s the most underrated movie by Fellini and one of the single most underrated movies of all time.

I have not though definitely keen to get to a few more Fellini films. Maybe towards the second half of this year or beginning of next once my Bergman study is all tied up.

Is Bergman page is coming soon?

Is Ingmar Bergman page coming soon?

Probably still a while away. I’m not rushing this one, going through about one Bergman film a week and currently up to Wild Strawberries. So the page may not come out till about September given his 40+ films.

I did a Bergman study a while ago. Didn’t get to every single one of his films but almost all.

My favorite period for sure is after Persona. His work with Liv Ullmann.

Really excited to get to that period, once you get to The Seventh Seal it really looks like one great film after another.

You’ll also really love Winter Light and The Silence. They’ll be like gems no one talks about.

I’m also really excited to know your thoughts on highly underrated Face to Face (1976).

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1950s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green