Carl Theodor Dreyer | 1hr 15min

Caught in the transition from silent to sound film, Carl Theodor Dreyer constructs a peculiar aberration of a horror film in Vampyr, absorbing us into a waking nightmare that only occasionally disrupts its eerie quiet with isolated lines of dialogue. Though it is a work of primal, symbolic imagery, it still presents exposition to us through intertitles, lifting passages from the book that occult fanatic Allan Gray is given at the start of the film – “The Strange History of Vampires.” Accounts of these creatures’ enslaved victims and mortal weaknesses are divulged here, guiding Allan through a supernatural conspiracy located in the castles and villages of rural France, and weaving an astoundingly cryptic allegory of European fascism.

Still, Vampyr cannot be so easily reduced to its plot or politics, both being relatively minimal compared to Dreyer’s hallucinatory dreamscape of shadows and shapes. While directors like James Whale and Tod Browning were establishing genre conventions within 1930s Universal monster movies, Dreyer’s horror was holding his audience at an obscure distance, calling on existential fears of violated self-agency repressed deep in our subconscious. If any stylistic comparison is to be made, then Vampyr draws on a heavy influence from F.W. Murnau’s silent expressionism, referencing the Gothic iconography of Nosferatu and traversing intricate sets in steady, measured camera movements like Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. Conversely, the dark spirituality interrogated here would also prove foundational to Ingmar Bergman’s severe minimalism a couple of decades later, sinking the warped souls of humanity into a lifeless, misty greyscale.

As for Dreyer himself, Vampyr marks an odd follow-up to The Passion of Joan of Arc, shifting from an aesthetic primarily consisting of close-ups to intricate wide shots composed with haunting precision. Interiors come alive with dancing shadows cast by invisible beings, while spoked wheels, curved scythes, and clawed angels imprint geometric shapes on giant canvases of negative space. Being shot on location in the pastoral commune of Courtempierre, much of the architecture here is authentically carved from stone and wood, and the sparsely patterned wallpaper of fleur-de-lis subtly infuses the setting with an air of historic French nobility too.

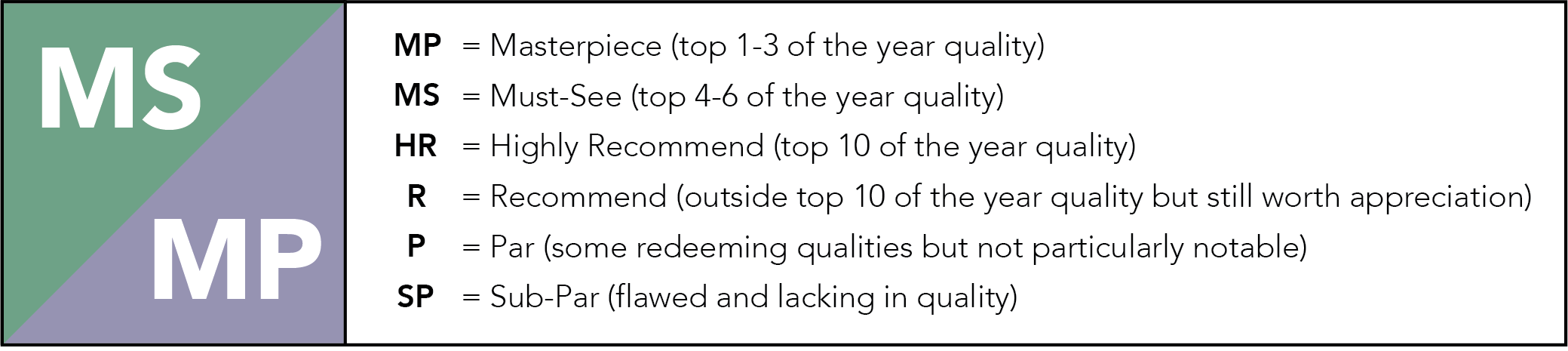

Even Dreyer’s characters frequently appear ornamental to his mise-en-scène, striking vivid poses and expressions in true silent cinema fashion. Our two main villains, the vampire Marguerite Chopin and the ghostly Lord of the Manor, are both withered old crones preying on the vitality of youth, which Dreyer archetypally represents here in the innocent Léone and her virginal white robes. After she is found wandering the castle grounds in a daze with a pair of bite marks on her neck, she begins acting erratically, baring her teeth in a sinister grin as her gaze mysteriously drifts across the ceiling. For our leading man Allan, it is his wide, curious eyes that capture our attention, and which also become the filter through which Vampyr’s second half is distorted into surreal visions of skeletons and corpses.

It is here that the influence on Bergman becomes even more apparent, particularly in Allan’s nightmarish discovery of his own body in a coffin which mirrors a strikingly similar dream in Wild Strawberries. Dreyer’s avant-garde experimentations express a deep mortal terror, lifting our hero outside of his body through an eerie double exposure effect, and directly taking his point-of-view from inside a coffin as he is carried to a grave and buried.

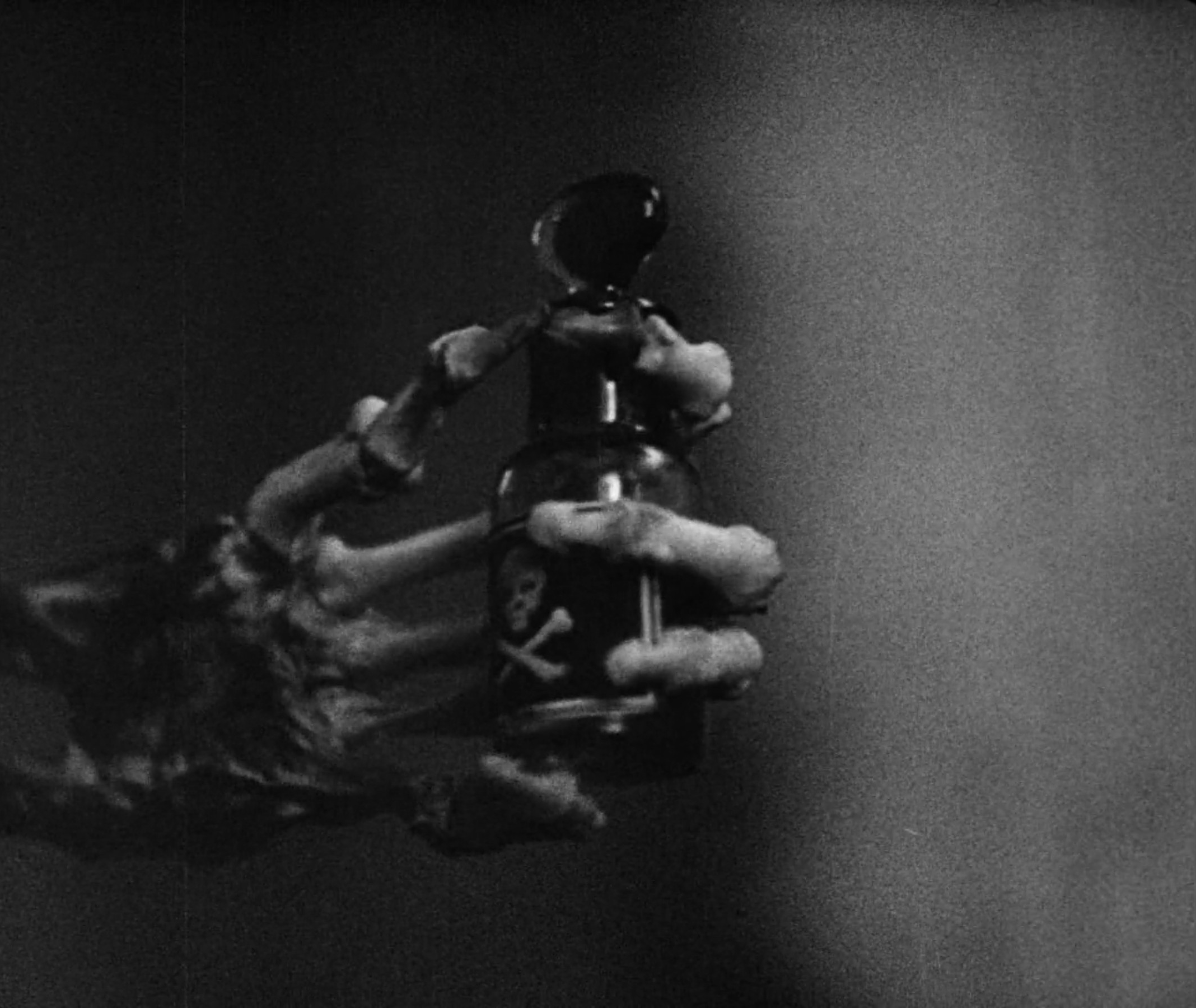

If there is any hope to be found in this bleak scenery, then it is smothered by the dense, grey clouds observed in Dreyer’s formal cutaways, holding back the daylight from reaching the village. Only when Allan eventually drives a large, metal stake through Marguerite’s heart do sunrays begin to pour through, beckoning him across a foggy river with a rescued Léone to a bright clearing on the other side. At the end of a long, dubious path of existential horrors, Allan finds love, heroism, and salvation, and yet it is only by exploring his nightmares that any of this was made possible to begin with. Whether Dreyer’s horror is to be interpreted as a political allegory, a spiritual fable, or merely a hypnotic progression of expressionistic images, Vampyr is designed to lull us into the same impressionable state as its victims, eerily calling upon our own subconscious desire for complete, psychological submission to the darkness.

Vampyr is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the Blu-ray can be purchased on Amazon.

One thought on “Vampyr (1932)”