Akira Kurosawa | 1hr 50min

Akira Kurosawa’s cynical landscapes of ambition, fate, and consequences make for a perfect marriage with Shakespeare’s grand historical tragedies. “This is a wicked world. To save yourself you often first must kill,” decrees Lady Asaji to her husband General Washizu in Throne of Blood, respectively standing in for Lady and Lord Macbeth, and possessing the same cutthroat megalomania. Like their literary counterpoints, Washizu and Asaji’s futures are written out by the prophecies of mysterious, supernatural forces far beyond their comprehension, raising them to great heights before sending them plummeting back to Earth as mortals terrorised by their own guilty consciences. The formal groundwork is there for a narrative steeped in centuries-old storytelling traditions, and yet it is through Kurosawa’s adaptation of the Scottish tragedy that Throne of Blood takes on new dimensions within feudal Japanese history, warping the doomed General Washizu into a figurehead of samurai brutality.

Especially significant to this reinterpretation of Macbeth is its fresh setting during the Sengoku period – a time of civil wars through the 15th and 16th century which saw samurai clans fight for political control of Japan. The romanticised code of honour they are often nostalgically associated with bears no relevance here, and instead leaves a moral vacuum for treacherous social climbers looking to exploit weakened political structures.

Kurosawa stages such power plays against bleak, greyscale landscapes of giant wooden fortresses and overgrown forests in Throne of Blood, spilling personal conflicts out into monumental battle scenes featuring hundreds of extras. Just because his visual stylisation doesn’t reach the level of Seven Samurai or Rashomon doesn’t mean his talent for deep focus blocking isn’t on lush display, but even more deserving of praise is his his aesthetic use of weather to confront his characters with the might of the natural world.

Most prominently, thick clouds of fog roll across his barren hills and valleys, obscuring horizons and disorientating Washizu as he makes his way home from war at the start of the film. It has an almost ethereal quality to it, seeming to emanate from that evil spirit which sits in a cage of bamboo and forecasts the samurai commander’s rise to power. Rather than taking the form of a witch, this soothsayer is far more ghostly in appearance, and later even wispily floats through a misty forest crowded with dense, black branches as it delivers the fateful second half of its prophecy.

The other spectre who materialises in Throne of Blood belongs to Washizu’s friend, Miki, who he kills out of paranoid concern for his own security. The ghost’s supernatural arrival unfolds in one smooth dolly shot at a banquet, pushing forward past an empty seat towards Washizu’s anxious face, and then pulling back to reveal Miki’s spirit now occupying that space. Whether he is an apparition that has come to haunt his murderer or merely a psychological manifestation of guilt, his mysterious appearance heralds even severer weather, with rain whipping the castle in a violent gale and lightning flashing across the sky.

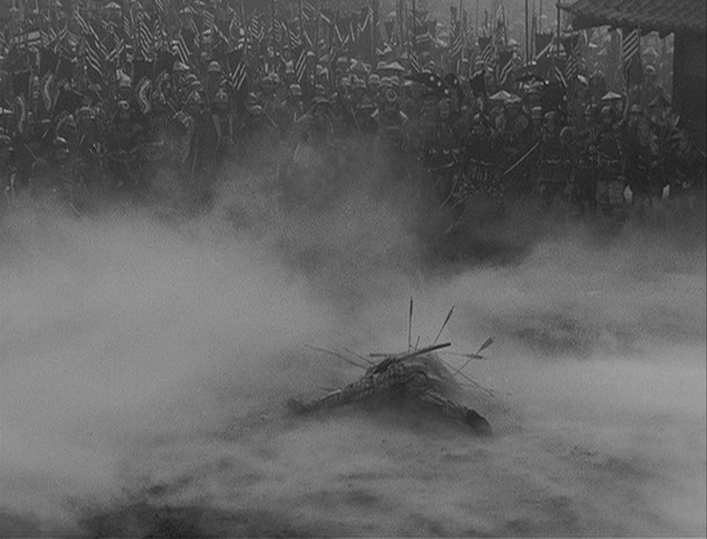

Even Kurosawa’s direction of the final act’s foretold ‘moving forest’ arrives like a primal force of nature, emerging from the thick fog and advancing with the heavy wind towards Washizu’s fortress. It is a smart choice for Throne of Blood to omit the passage from Macbeth which plainly describes the enemy’s disguise, as Kurosawa instead hits us with the frightening sight of these trees coming to life at the exact moment that Washizu recognises his own impending mortality. His ego and power may be mighty, but even that cannot stand up against the power of the ancient, formidable powers of fate.

Motivated as much by fear as he is ambition and arrogance, the crazed Washizu does not waver, and neither does Toshiro Mifune in his single greatest moment as this Japanese incarnation of Macbeth. His fiery eyes light up the screen as a gleeful snarl stretches across his face, while behind him Kurosawa sets a majestic military backdrop of samurai raising flags and banners in crumbling fealty. This leads into another alteration of Shakespeare’s original text, and perhaps the most significant. With the prophecy that ‘no man of woman born can harm Macbeth’ absent, Washizu’s death is placed in the hands of his own disillusioned men, imbuing this legend with a revolutionary turmoil that grounds it even deeper in Japan’s politically unstable Sengoku period.

In extreme contrast to Mifune’s wide, crazed eyes, Isuzu Yamada displays Lady Asaji’s expressions like wooden masks, not unlike those worn by performers of Noh theatre. The guilt she exhibits is of an entirely different kind to Mifune’s fierce insecurity – rather than lashing out, she is found delusionally trying to clean her hands of blood that isn’t there, with her face contorted into the static image of a demonic hannya mask and her honed gestures mimicking those of Noh tradition.

Kurosawa continues to weave these elements of Japanese theatre even deeper into its structure through his austere musical bookends, summarising Throne of Blood’s narrative into a couple of short, choral verses as fog continues to roll through the grey scenery.

“Look on the ruins,

Of the castle of delusion.

Haunted now only,

By the spirits of the dead.

Once a scene of carnage,

Borne of consuming desire,

Never changing,

Now and for eternity.”

Like the music of Noh theatre, these chants are limited in tonal and dynamic range, moving through repetitive patterns that restore a sense of order to Kurosawa’s world of subversive chaos. Tradition is the bedrock of these cultures, as ingrained in their social structures as it is in the laws of a calm yet overwhelming universe, and continuing to be carried out by forces of nature and destiny when humans fail to uphold its rigorous standards. Few films have truly captured the cinematic potential of Shakespeare onscreen in the art form’s history, and perhaps none with as much creative formal finesse as Kurosawa’s cynical exposure of the treacherous dishonour entrenched in samurai history.

Throne of Blood is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green