Park Chan-wook | 2hr 9min

Given that the title Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance could refer to either one of its two main characters, the challenge it poses is particularly fraught with self-contradictions. To have sympathy for the deaf-mute factory worker Ryu is to recognise the desperate circumstances he has found himself in with a group of dishonest black-market organ dealers, driving him to raise money for his sister’s kidney transplant by taking take a young girl hostage. Even if his actions are cruel, his motivations are reasonable, though such nuances are irrelevant to wealthy business owner Park Dong-jin. After all, it is his daughter who has been targeted, and now he too is set on a path of retribution against her kidnapper.

Expressing sympathy for both men is a tricky balance to strike, but it is one which Park Chan-wook achieves by transmuting it into a new feeling – pity. Of all the films in his Vengeance trilogy, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance may be the purest distillation of his nihilistic ethos, recognising humanity’s innate yet self-destructive need for violent anger in its formal mirroring between two angry, wounded men at odds with each other.

One could draw parallels between Park and his Austrian contemporary Michael Haneke in their icy, detached depictions of violence, often sitting in remote wide shots that distance us from both aggrieved tormentors and victims, yet there is a very clear division in their aesthetics. Where Haneke is rigorously committed to the humourless minimalism of such acts, Park injects them with a wry sardonicism, relishing the elegant grotesqueness of a white shirt slowly turning red from attempted seppuku, or the clouds of blood left behind a body being pulled through running water.

The riverbank set piece we return to multiple times might even be interpreted as a sacrificial altar of sorts given that it hosts much of the film’s body count. If there is any god being served here though, then maybe it is our own human desire to see suffering dealt out as a form of justice. In that sense, Park’s recurring overhead shots serve a brilliant formal purpose in placing us above these characters, like divine witnesses to the dramatic irony playing out across Ryu and Dong-jin’s parallel plotlines. The gentle stream of water, the loose stones, and the curved rock platforms of the river look breathtaking from these high angles, compelling us to revel in the perverse beauty of cold, dead bodies returning to nature.

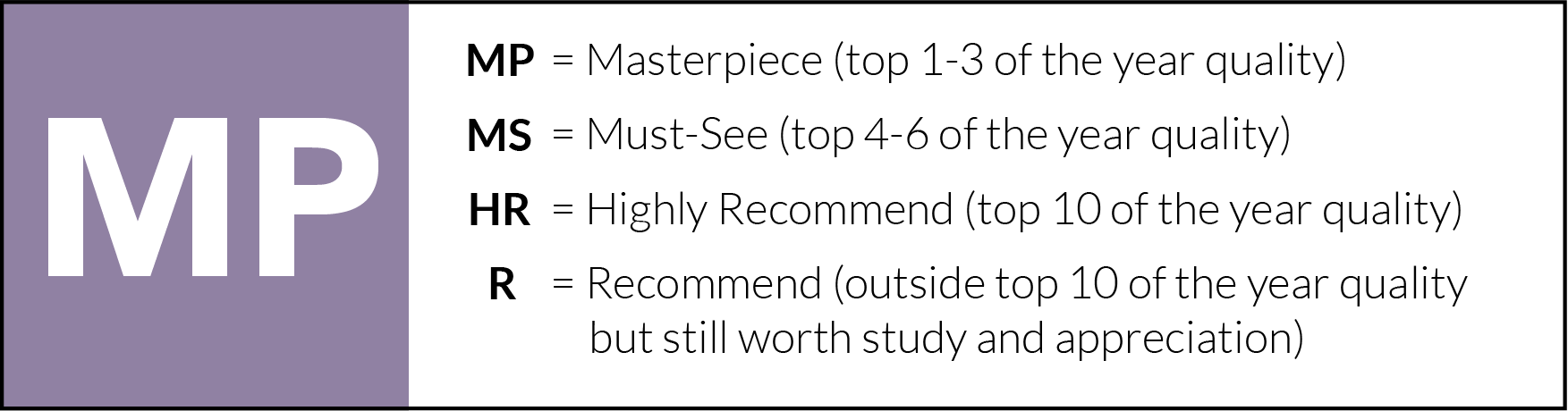

Through this godlike, omniscient perspective, Park expands the world of Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance to a magnificent extent. While Dong-jin comes from the prestigious upper end of Korean society, Ryu is confined to a small, messy apartment that shares a wall with four other young men, denying any of them the right to privacy. At some points the shifting of Park’s camera between various points-of-view underscores a dark dramatic irony, positioning us with the neighbours who masturbate to what they interpret as screams of pleasure, before physically crossing the barrier to show Ryu’s sister crying in pain from her kidney infection. Later, Park formally recalls this moment in reverse when Dong-jin presses his ear against the wall to hear what he believes is an investigator speaking to neighbours, while the camera dollies to the other side and reveals the source as a radio news report.

Under Park’s idiosyncratic direction, such keen visual storytelling is precisely choreographed and thrillingly executed, eschewing dialogue for large stretches of time while we cut between this pair of lone wolves doggedly hunting down their prey. His editing and camera movements are measured as this narrative unfolds to the sounds of the Uhuhboo Project’s experimental score, but virtually every shot he lands on possesses its own visual eccentricity too in wide-angle lenses, unconventional framing, and one of the greatest modern uses of deep focus photography.

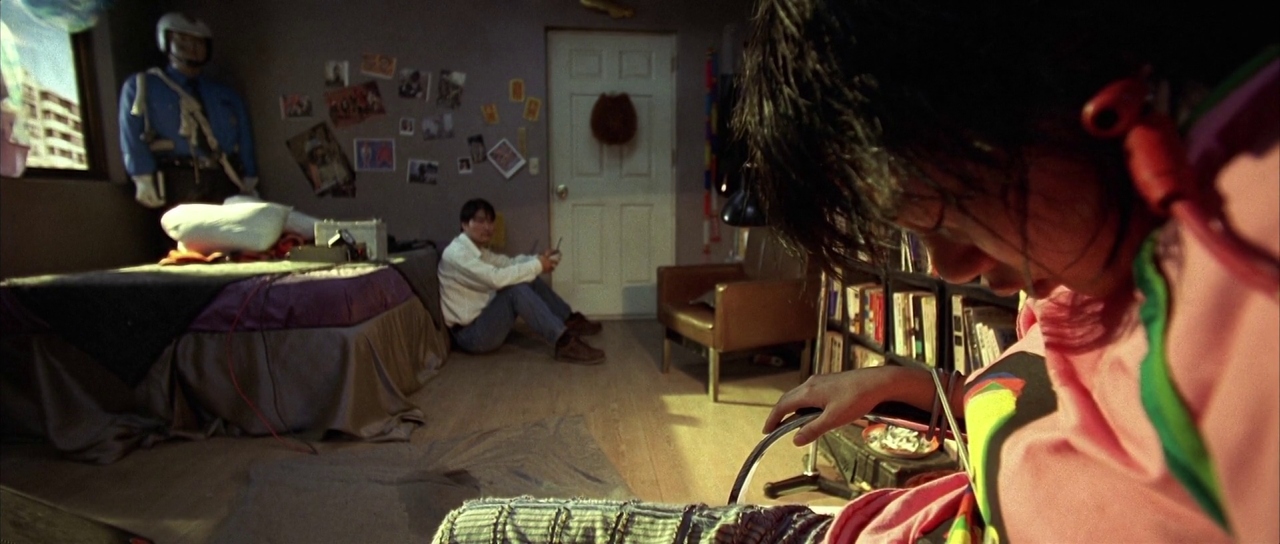

Perhaps the most astoundingly rigorous of all Park’s creative choices though is the palette of murky greens that this morally tainted culture is so steeped in. This is a level of world building akin to Krzysztof Kieslowski, deeply engaged with the metaphysical connections between strangers united within common circumstances, and tonally expressed in a set of formally binding aesthetics. Here, green tones light up Ryu’s dyed hair like a mint-coloured beacon and verdantly illuminate his shabby apartment, while on Dong-jin’s side they accompany him through up-class urban environments and into the crematory where he mournfully bids farewell to his daughter. While we suffer one gut punch after another with these characters and watch them fall into retaliatory anger, Park’s cool tones and sustained pacing maintain a calm, chilly composure.

It is the perfect stylistic match for the film’s visceral, pessimistic humour too, predominantly keeping us at a distance while intermittently making us flinch. For what is supposedly a godless universe, it certainly enjoys rubbing each character’s reckless mistakes in their faces, opening a spot for Ryu’s sister on the hospital waitlist almost immediately after he loses his money to the black-market, and later incidentally landing him next to the sheet-covered corpse of his girlfriend, Yeong-me, on an elevator. It isn’t that he and Dong-jin are ineffective in accomplishing their quests for revenge, but both are victims of their own short-sightedness, refusing to see the long-term consequences of their actions. Especially for Dong-jin, the warning of his comeuppance is right there in front of him when a half-dead Yeong-me begs for mercy.

“If anything happens to me, my organisation is a terrorist group. They’ll kill you. For sure. I gave them your picture. If you want to live, just leave me. This is for your sake.”

This is also the threat which haunts him in the final scene after his vicious murder of Ryu at the river, materialising in a daunting composition of four resolute faces staggered into the background, knowingly staring at him. Retribution is not a solution in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, but an endless chain of victims seeking mutually assured destruction, foolish enough to believe that they might escape the destinies they have chosen. Then again, maybe we can find some pity for these poor creatures governed by their basic human instincts, futilely hoping that it might satiate their innate, bloodthirsty hunger for justice.

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is not currently streaming in Australia.

2 thoughts on “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002)”