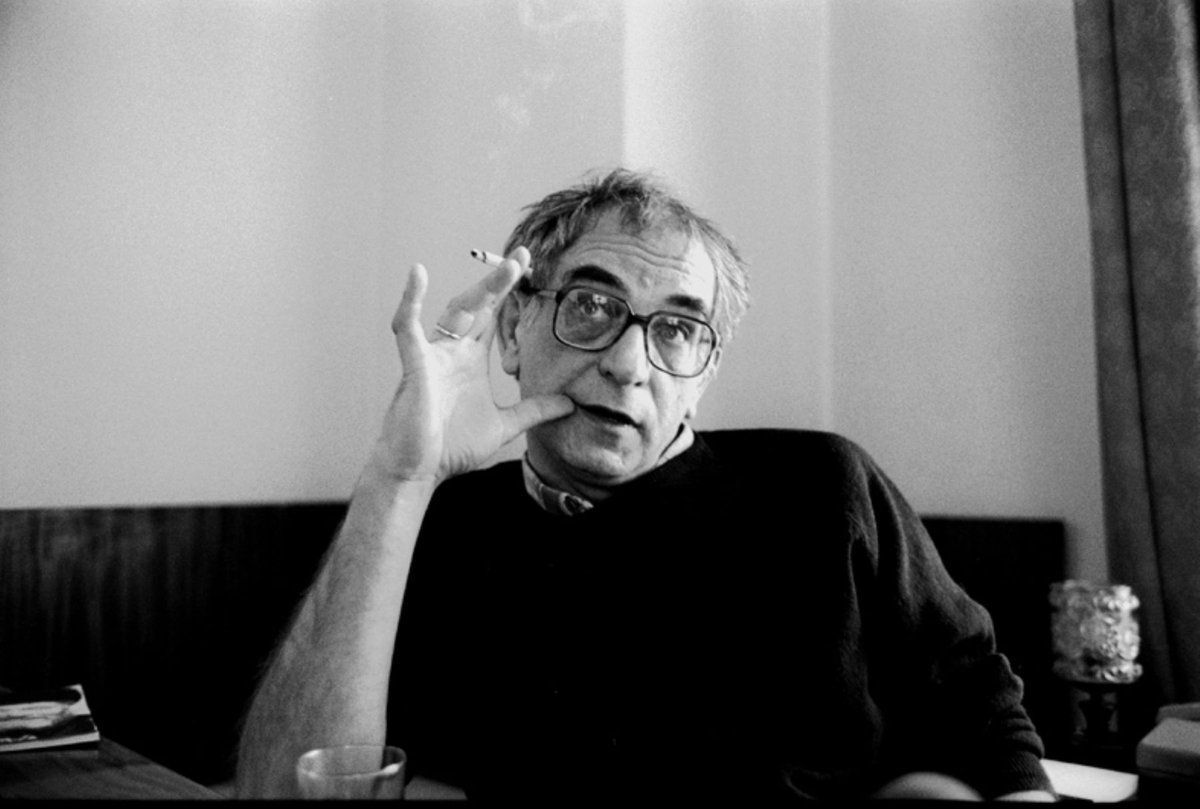

“If I have a goal, then it is to escape from this literalism. I’ll never achieve it; in the same way that I’ll never manage to describe what really dwells within my character, although I keep on trying.”

Krzysztof Kieslowski

Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. A Short Film About Killing | 1988 |

| 2. Dekalog | 1989 |

| 3. The Double Life of Veronique | 1991 |

| 4. Three Colours: Blue | 1993 |

| 5. Three Colours: Red | 1994 |

| 6. Three Colours: White | 1994 |

| 7. A Short Film About Love | 1988 |

| 8. Blind Chance | 1981 |

| 9. No End | 1985 |

| 10. Camera Buff | 1979 |

Best Film

A Short Film About Killing. It is not just a highpoint of the Dekalog series, but of Kieslowski’s entire career, delivering a punishing treatise on the injustice of the death penalty through a sickly, jaundiced filter. This vision of Warsaw is a barren wasteland of corruption, and that seeps all through Kieslowski’s grotesque photography and methodical staging. The story is split in two halves, each ending with a brutal murder, and the formal mirroring is impeccable. The destruction of human life is a sacrilegious transgression of nature in his eyes, every bit as repulsive as the desolate society which either passively or righteously condones it.

Most Overrated

Nothing. Everything from Kieslowski is either well-rated on the TSPDT list or underrated. Given the formal complexity of much of his work, it is naturally more likely that audiences will miss his genius rather than overestimate it.

Most Underrated

A Short Film About Killing. This currently sits at #8 of 1988, which is a significant miss from the critical consensus. It deserves to be in the top 3 (along with Distant Voices, Still Lives and Dead Ringers), if not sitting at number 1. It was also the first theatrical cut of a Dekalog episode, so my guess is that many critics are divided over whether they should consider it as part of the series or on its own. My vote obviously goes to the latter.

Gem to Spotlight

Dekalog. The cinematic launchpad for the rest of Kieslowski’s great career can’t be overlooked. Few television series have reached this level of artistic accomplishment, as Kieslowski dedicates each of its individual episodes to one of the Ten Commandments, crafting an epic drama around a set of strangers living in a single Warsaw apartment complex. We are gifted an omniscient perspective into their stories, each one of which possesses its own distinct style while being bound together by a series of common motifs. Kieslowski’s characteristic use of iconography and cutaways also lend spiritual significance to these characters’ journeys, wrestling with complex moral dilemmas that attempt to reconcile traditional moral imperatives with modern cultural values.

Key Collaborator

Krzysztof Piesiewicz. It is hard to glean how much of a coincidence it is that Kieslowski’s great artistic breakthrough with the Dekalog was also when he started co-writing his screenplays with Piesiewicz. Clearly Kieslowski’s stylistic accomplishments are his own, and the narrative fascinations with fate, death, and religion began long before his arrival, but it is evident that his work was far stronger when Piesiewicz was in the picture, who worked on every Kieslowski film from 1988 to his death. These screenplays are obscure and profound in their philosophical ambitions, centring complex characters being drawn towards predetermined fates far beyond their control.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

Targeting Polish Politics

As a film student with ambitions in the realm of political art, Kieslowski began his career making both short and feature-length documentaries, travelling Poland to research and shoot the day-to-day lives of labourers, soldiers, and city people. After recording interviews with workers protesting against food shortages, he quickly found himself being heavily censored by Polish Communist authorities, though this only incensed him further and pushed him to branch out into narrative filmmaking.

His non-documentary debut, Personnel, was broadcast on television and struck a chord at the Mannheim Film Festival, winning him first prize. It wasn’t until The Scar though that he was able to combine his intelligent political voice with artistic potency, setting him up as an important figure in the realm of social realism. Through his following films he developed a didactic and pointed cinematic style, targeting specific areas of Polish culture and politics unique to the time period such as the introduction of martial law, all the while continuing to wrestle with censors. Blind Chance was hit particularly hard with its release being delayed by authorities for six years, and not being seen by the public until 1987. Even today, there is still a single scene depicting the police beating up a citizen that has not been fully recovered.

Across the late 70s and mid 80s, Kieslowski continued dropping in pieces of conceptual philosophy and surrealism. There was already a hint of it in the sparse, ethereal score of The Scar, but in the parallel timelines of Blind Chance and the ghostly manifestations of No End, it became clear that he was starting to head in more metaphysical directions. Of course, this would all foreshadow the complete departure from politics in his later career, and a submission to personal, spiritual questions.

A Television Breakthrough

While Kieslowski was beginning work on his most ambitious project yet, the Dekalog series, he was asked by his producers to expand two of its episodes into feature-length films to make for easier international distribution, thus giving us A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love.

These films were released in 1988, a year before the Dekalog would make its television debut, and both marked a dramatic step up in artistic quality from his previous films, individually developing colour palettes that are formally tied to their narratives. This would go on to be an identifying characteristic of Kieslowski’s later work, even becoming the stylistic basis of his Three Colours trilogy in the 1990s. Here though, it was A Short Film About Killing which especially leapt out for its harsh depiction of Warsaw as a dystopian hellhole, laying vignettes over sepia images of social decay and violent murder, and making a powerful statement against the death penalty.

The arrival of the Dekalog series in 1989 only cemented the genius that took over film festivals the previous year. Inspired by a 15th century artwork that depicted the Ten Commandments in scenes from that period, Kieslowski strived to make a modern cinematic equivalent within the social and political context of late-Communist era Poland. This wasn’t just the start of his interest in God-like, omniscient perspectives that study the hidden interconnections between unassuming strangers. This was also the beginning of his commitment to long-form cinema, structuring series around cultural ideals whether they be religious imperatives or the colours of the French flag.

Questions of Faith and Philosophy

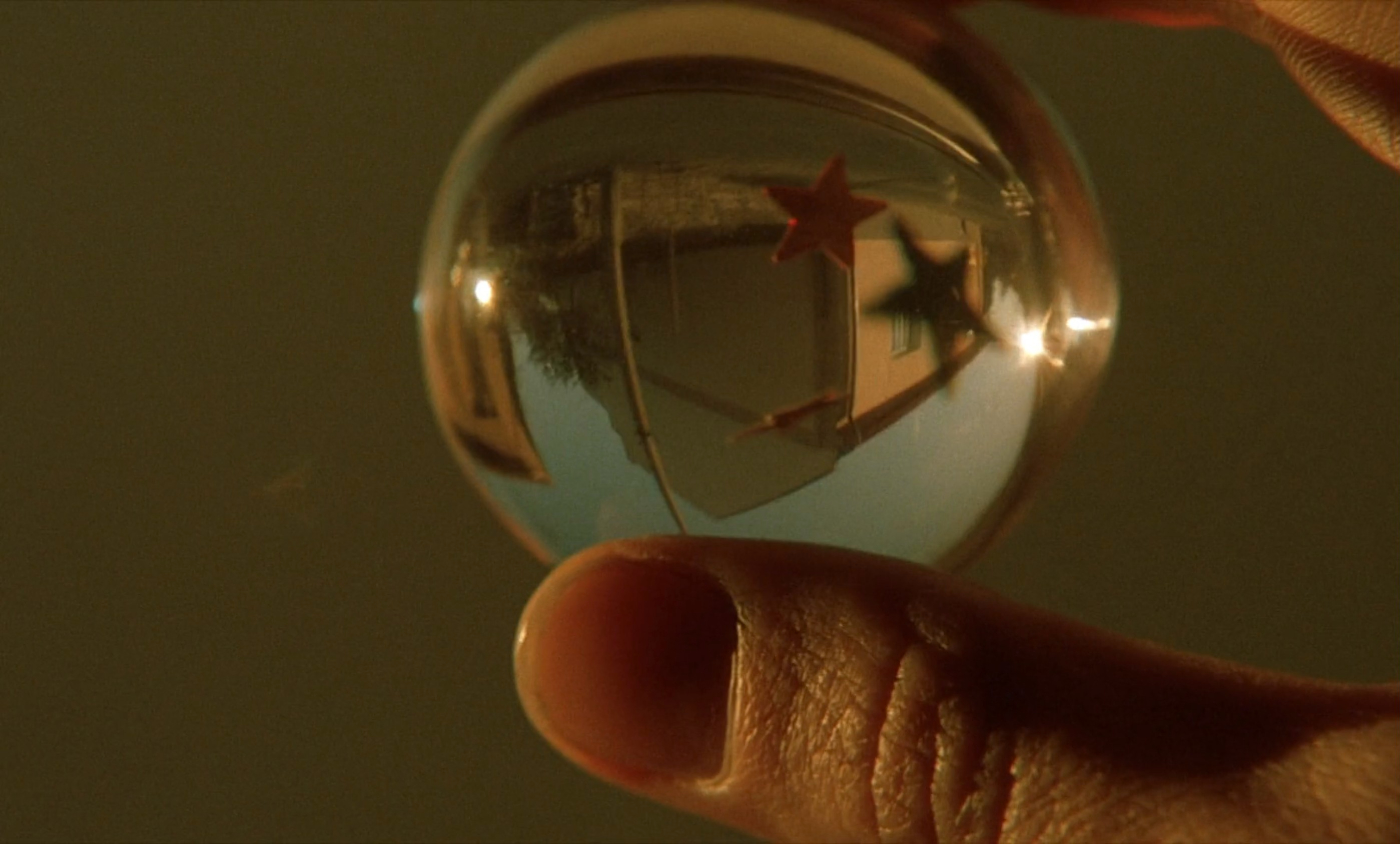

By the 1990s, Kieslowski was well and truly on a roll, delivering masterpiece after masterpiece. Despite being the only standalone film from the latter half of his career, The Double Life of Veronique stands as one of his finest cinematic accomplishments, displaying all of his most recognisable stylistic trademarks that would continue to be represented in his subsequent Three Colours trilogy. The use of glass to reflect and distort images is particularly characteristic of Kieslowski, gazing through orbs, lenses, and windows to empathetically consider alternate perspectives. It has a distancing effect as well though, as if to suggest we can never truly cross that barrier into other people’s lives.

In The Double Life of Veronique, Kieslowski frequently combines those glass shots with his cutaways, another distinguishing feature of his that stretches even further back to his earlier films. A dissolving sugar cube, a pair of grasped hands, a cracked glass of beer – these tiny, delicate representations of larger ideas offer deeper meanings to his stories and characters, stepping beyond the immediate plot to examine the ways human experiences are reflected in the micro-details of their surroundings. They also practically break up the flow of Kieslowski’s narrative, taking the time to retune our sensitivity and perspective, before letting us re-join our characters.

It is worth noting the yellow and green hues that hang in the air in The Double Life of Veronique, but the colour palettes which permeate the Three Colours trilogy go without saying. In representing the French flag as a film series, Kieslowski is able to take the time to examine philosophical applications of its national values – liberty, equality, and fraternity. Red in particular stands out as being most in line with his previous metaphysical fascinations as laid out in Blind Chance, the Dekalog, and The Double Life of Veronique, studying the passing connections between strangers and the alternate lives we could have lived were it not some twist of fate or divine intervention. Much like the ending of Blind Chance, the conclusion of Red sees Kieslowski gather a small ensemble of characters we have been following but who are unknown to our main protagonist, uniting the Three Colours trilogy within a single scene.

It was at the premiere of Red at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival that Kieslowski announced his retirement from film, claiming his belief that literature could achieve greater things than cinema. Evidently there was a change of heart at some point, as he began to work on a new trilogy with films based on the concepts of Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory. Though he had finished writing them, he passed away in 1996 from a heart attack, and two of the three screenplays were later adapted by other filmmakers.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1976 | The Scar | R |

| 1979 | Camera Buff | R |

| 1981 | Blind Chance | R |

| 1985 | No End | R |

| 1988 | A Short Film About Love | HR |

| 1988 | A Short Film About Killing | MP |

| 1989 | Dekalog | MP |

| 1991 | The Double Life of Veronique | MP |

| 1993 | Three Colours: Blue | MP |

| 1994 | Three Colours: White | MS |

| 1994 | Three Colours: Red | MP |

Brilliant work here again, especially love the way you’ve structured this director page and how much depth you explore not only his filmography but also some bits of his personal life. Sadly the only work I’ve seen from Kieslowski is Double Life of Veronique, but I do plan to check out the 3 Colors Trilogy soon, which I’m excited for. Keep it up mate!

Thanks Chase, much appreciated! Keen to hear your thoughts on the Three Colours trilogy, Kieslowski is a very rewarding filmmaker to get into. I hadn’t seen anything from him before beginning my study.

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green