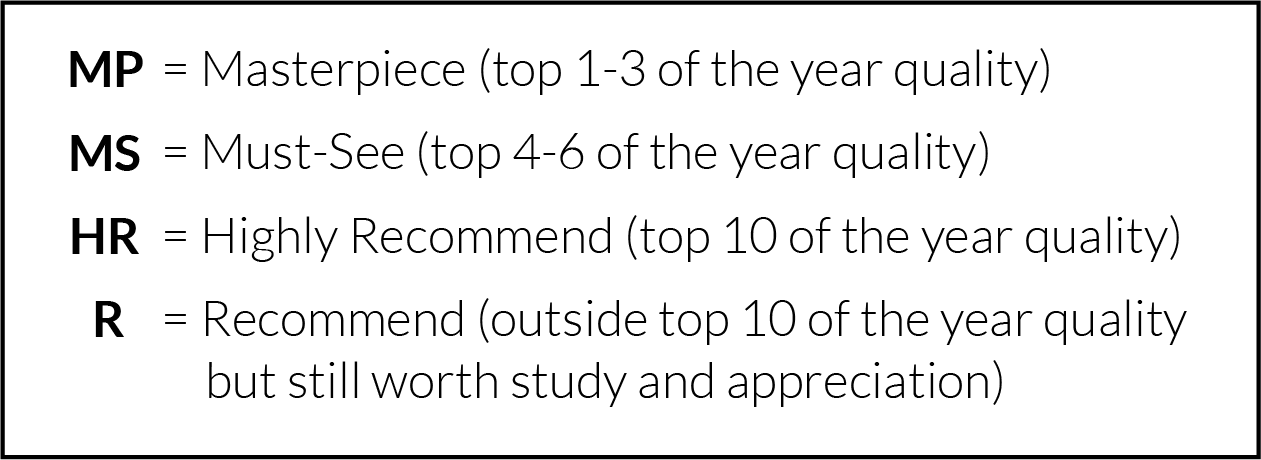

“Film as dream, film as music. No art passes our conscience in the way film does, and goes directly to our feelings, deep down into the dark rooms of our souls.”

Ingmar Bergman

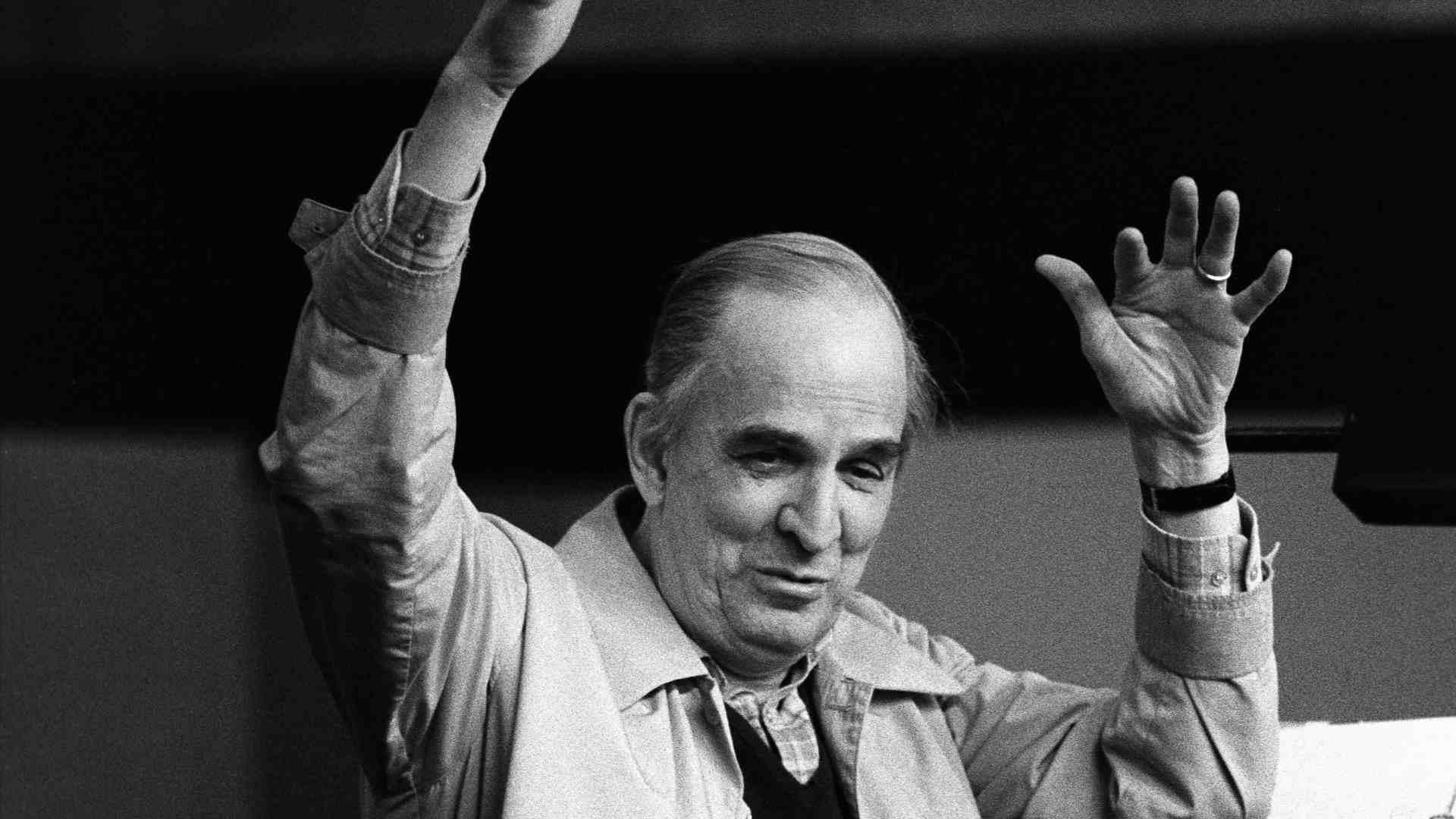

Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. Persona | 1966 |

| 2. The Seventh Seal | 1957 |

| 3. Fanny and Alexander | 1982 |

| 4. Cries and Whispers | 1972 |

| 5. Autumn Sonata | 1978 |

| 6. Winter Light | 1963 |

| 7. The Virgin Spring | 1960 |

| 8. The Silence | 1963 |

| 9. Wild Strawberries | 1957 |

| 10. Hour of the Wolf | 1968 |

Best Film – Persona

This may stand as the finest formal synthesis of Ingmar Bergman’s intimate visual style of close-ups and his deeply psychological subject matter, examining the perplexing duality which simultaneously defines humans as social beings and distinct individuals. All abstract truths conceived in one’s mind must be filtered through some sensory expression to reach the outer world, and Bergman does not discount his own film from that inevitable distortion. The raw materials of cinema itself become integral to Persona’s very form, fully recognising the impossible task of creating any pure representation of reality. It is deceitful in its purposeful manipulations, but also intricately designed to evoke truths through bold, symbolic expressions. Persona features career-best work from cinematographer Sven Nykvist, editor Ulla Ryghe, and actresses Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson, but it is in the way Bergman formally integrates every element of cinema at his disposal to create such an obscure, avant-garde interrogation of identity that places it right at the top.

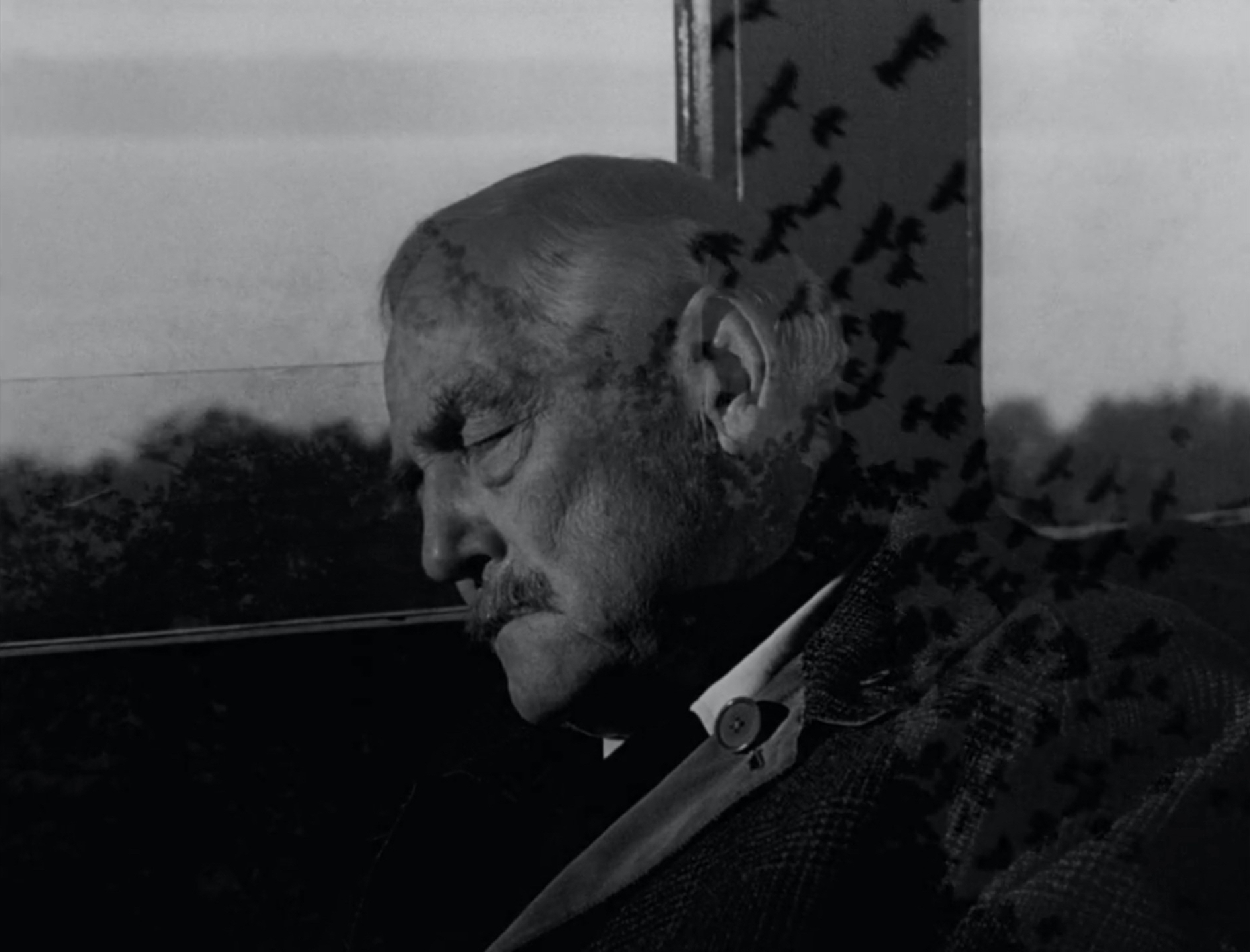

Most Overrated – Wild Strawberries

To be fair, this can only be considered overrated by comparing where it sits on my list versus the TSPDT ranking. There, the critical consensus places it as the 61st best film of all time, and Ingmar Bergman’s 2nd best film after Persona. I’ve got 8 other Bergman films ahead of it, but that has more to do with the strength of those than the weakness of Wild Strawberries, which is still a borderline masterpiece. There are very few negative criticisms that can be levelled at this beautifully surreal meditation on mortality, regret, and lost time.

Most Underrated – All These Woman

This sits far outside the TSPDT top 1000 at #9283, putting it in the very bottom tier of Ingmar Bergman’s films on the site. It has also been critically panned from some great critics, including Roger Ebert who called it Bergman’s worst film. This brightly coloured pastiche is certainly about the furthest thing one could imagine from the black-and-white meditations on faith which have defined his greatest artistic triumphs up to this point. Even his previous comedies such as Smiles of a Summer Night carry a more eloquent wit than the slapstick and buffoonery he happily indulges in here, which we see one snobbish music critic awkwardly inflict on the film’s country chateau setting while visiting famed cellist Felix. Flawed it may be, but Bergman’s experimentations with colour palettes and irreverent self-reflexivity build towards a single, unified point – art has no real relevance to the narcissistic pretensions of artists.

Gem to Spotlight – Sawdust and Tinsel

This would later be topped by many other Ingmar Bergman films, but in 1953 it was his best film to date, and the strongest hint that he was capable of creating truly great cinema. Life is a circus that creates entertainment out of humiliation, he posits in its central metaphor, and in his rich staging and screenwriting he needles its existential drama with a finer, wittier point than ever before. He finds both sympathy and pity for its hapless fools doomed to eternal ridicule, yet continues to undercut their dreams of escape with constant reminders of their own inadequacy. If there is any solace to be found, at least the humiliating stories they accumulate will make for great comic fodder down the track, offering momentary distractions from their sad, squalid circumstances.

Key Collaborator – Sven Nykvist

There’s a good number of actors who could fill this slot too, including Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, Ingrid Thulin, and Gunnar Björnstrand, but from The Virgin Spring onward Sven Nykvist is Ingmar Bergman’s most frequent and consistent collaborator. If he isn’t history’s greatest cinematographer, then he’s at least in the top 3, proving his hand at capturing both the harsh austerity of Sweden’s barren scenery and the vibrancy of rigorously curated colour palettes. Most of all though, it is his intimate close-ups which define his aesthetic with Bergman, turning faces into landscapes with the potential to be shot in an unlimited number of angles, lighting setups, and arrangements within ensembles.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

Early Melodramas (1946 – 1950)

Although Ingmar Bergman’s love of cinema began during his years as a literature and art student at Stockholm University College, his fascination with human relations, faith, and dreams are rooted even more deeply in his childhood. The estrangement he felt from his father, a strict Lutheran minister, would manifest in many of his films as crushing emotional and spiritual isolation, especially taking the form of melodramas in his early years.

The development of his artistic voice was slow but sure. Many of the films from this era of his career were romances and tragedies that saw young love wither into resentment, with some mix of suicide, rape, trauma, and cheating thrown in the mix. These narratives also played heavily on flashbacks contrasting the innocence of youth against the depressing burden of reality, further expressed through some sharp yet eloquent eviscerations.

“I hate you so much that I want to live just to make your life miserable. Raoul was brutal. You took away my lust for life.”

Rut (Thirst, 1949)

Easily the most consequential stylistic trait that Ingmar Bergman would start developing around this time though was his blocking and framing of faces in close-ups. Port of Call is the earliest instance of this, but Thirst would push it a little further with Bergman’s first notable use of what would become one of his trademark shots – the profile of one face half-obscuring another behind it.

The Summer Years (1951 – 1955)

This is the most suitable title for the next stage of Ingmar Bergman’s career for two good reasons. From 1951 to 1955, he directed three films with Summer in the title – Summer Interlude, Summer with Monika, and Smiles of a Summer Night. Later in his career he would tick off the three other seasons with The Virgin Spring, Winter Light, and Autumn Sonata, but for now his fascination laid in this fleeting period of daylight, growth, and abundance that precedes darker, colder days.

This is also the era when his cinematic artistry and reputation began to lift off the ground, seeing him further refine his style and hit greater heights than he did in the 1940s. Romantic tragedies and melancholy flashbacks are often still very much at the centre of his work, meditating on the fickle nature of human desire that keeps his characters from establishing trust in their relationships, but so too is he broadening his range as well. Smiles of a Summer Night is his first comedy, taking a light-hearted spin on A Midsummer Night’s Dream with its intricate web of affairs between aristocrats, while Sawdust and Tinsel turns a circus troupe into an existential metaphor for life’s cruel farce.

“We make art. You make artifice. The lowest of us would spit on the best of you. Why? You only risk your lives. We risk our pride.”

Mr. Sjuberg (Sawdust and Tinsel, 1953)

Gunnar Fischer’s contributions as Ingmar Bergman’s regular cinematographer during this period must be noted, contributing his eye for barren landscapes and deep focus imagery. Another Bergman trademark emerges for the first time in Smiles of a Summer Night with the parallel faces lying side-by-side, while his actors’ performances flourish even more under the intimate inspection of his close-ups. Bibi Andersson, Eva Dahlbeck, and Gunnar Björnstrand each get their time in the spotlight here, but it is Harriet Andersson who truly defines this period for Bergman as an actress, exerting a feminine sexuality and emotional depth that was far from common in the 1950s.

Philosophical Dramas (1957 – 1963)

Before 1957, no one saw a masterpiece like The Seventh Seal coming from Ingmar Bergman. To then follow that up with Wild Strawberries in the same year makes for an accomplishment rivalled by very few in film history – one must think of Josef von Sternberg dominating 1930 with both The Blue Angel and Morocco, or Francis Ford Coppola releasing both The Godfather Part II and The Conversation in 1974.

These two films also mark a new trajectory for Bergman, who was now staring down the philosophical questions that had previously only lingered beneath the surface. The silence of God would occupy his thoughts in The Seventh Seal, and would become a running theme throughout the rest of this period until The Silence in 1963, while Wild Strawberries draws us into the dreams and memories of an elderly professor looking back on a life of regrets. Those flashbacks that Bergman had been using for so long by this point manifest with nightmarish unease here, similarly setting him down a path of cinematic surrealism.

“Is it so awfully unthinkable to conceive of God with one’s senses? Why should He conceal Himself in a fog of half-spoken promises and unseen miracles? How are we to believe the believers when we don’t believe ourselves? What will become of us who want to believe but cannot? And what of those who neither will nor can believe? Why can I not kill God within me? Why does He go on living within me in a painful, humiliating way, though I curse Him and want to tear Him out of my heart? Why does He remain a treacherous reality of which I cannot rid myself? Do you hear me?”

Antonius Block (The Seventh Seal, 1957)

Man’s faith in God, or the lack thereof, is clearly a subject that torments Ingmar Bergman in this period. It was already very clear that Bergman was an immensely talented writer of dialogue, but it wasn’t until this point that he started writing some of the greatest screenplays of all time. The Virgin Spring lays out a compelling allegory of Christ’s sacrifice, while Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence constitute his unofficial ‘Faith’ trilogy, each in conversation with each other on the matter. The resentment that his characters hold towards each other frequently spills over into poetic vitriol in these films, aimed at viciously tearing each other down, though frequently revealing more about the speaker than the target of their derision.

“I’m tired of your loving care. Your fussing. Your good advice. Your candlesticks and table runners. I’m fed up with your short-sightedness. Your clumsy hands. Your anxiousness. Your timid displays of affection. You force me to occupy myself with your physical condition. Your poor digestion. Your rashes. Your periods. Your frostbitten cheeks. Once and for all I have to escape this junkyard of idiotic trivialities. I’m sick and tired of it all, of everything to do with you.“

Pastor Tomas Ericsson (Winter Light, 1963)

The parallel move away from Summer-based films as well couldn’t be harsher – frozen landscapes, rural churches, and foreign hotels completely isolate his characters in unwelcome environments, cutting them off from God and the rest of humanity. His home island of Fårö features for the first time among these settings too in Through a Glass Darkly, becoming its own metaphor of emotional and spiritual solitude.

Two of Ingmar Bergman’s greatest actors join his troupe in this period around this time, with Max von Sydow making an enormous breakthrough as the disenchanted knight Antonius Block in The Seventh Seal, and Ingrid Thulin leaving a huge imprint on Wild Strawberries, Winter Light, and The Silence. So too does Sven Nykvist properly enter the picture here, taking the reigns from Gunnar Fischer and establishing a working relationship that would last for decades. He had done some very solid work before on Sawdust and Tinsel, but the severe minimalism of The Virgin Spring, Winter Light, and The Silence stands among some of Bergman’s finest visuals, delivering magnificent theological symbolism.

Experiments in Form (1964 – 1982)

With The Silence capping the end of his thematic trilogy in 1963, Ingmar Bergman claimed he was done questioning the existence of God, and new avenues began to open that allowed him greater artistic freedom – not that his shifting focus was immediately met with widespread acclaim. All These Women is a huge swing in visuals and writing that is about as far from Bergman’s typical style as possible, comically indulging in slapstick and satire that is ridden with flaws, yet still sticks the landing. It is also his first film shot in colour, which he wouldn’t return to again until The Passion of Anna in 1969. From then on though, it became the default in his filmmaking, seeing him quickly become a master of colour in Cries and Whispers and Fanny and Alexander – two of the most beautifully shot films in history.

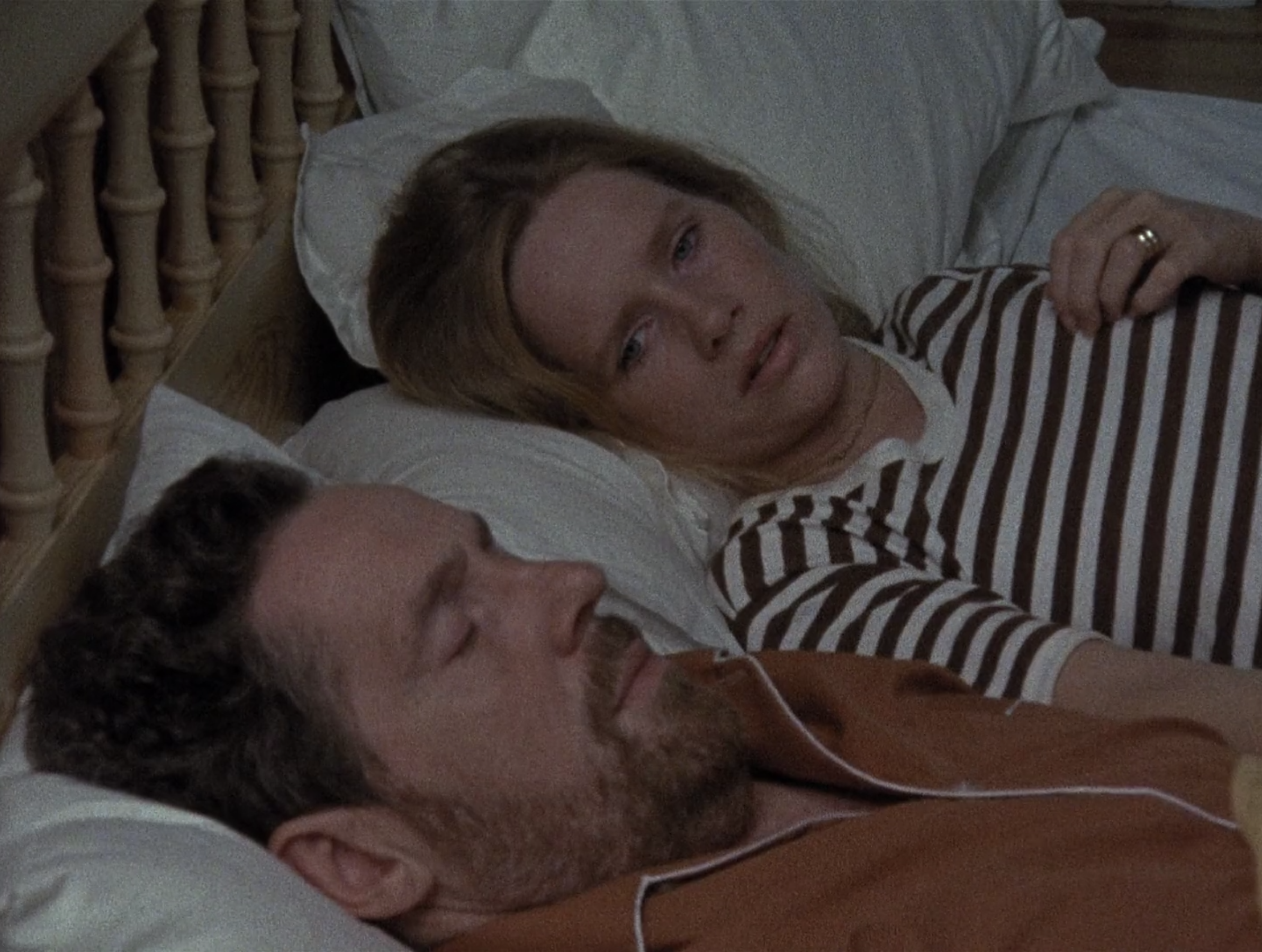

No longer sticking purely to philosophical dramas, Ingmar Bergman began exploring other genres as well. Hour of the Wolf sees him take command of psychological horror as an interrogation of mental illness, Shame witnesses a married couple emotionally ripped apart by war, and Scenes From a Marriage lays out an enormous marital epic that is viscerally uncomfortable in its realism. He had been examining the constraints of human relationships since his earliest days of filmmaking, but this is easily his purest distillation of these concerns, trapping us in confined rooms with a husband and wife on the verge of divorce.

“We’re emotional illiterates. We’ve been taught about anatomy and farming methods in Africa. We’ve learned mathematical formulas by heart. But we haven’t been taught a thing about our souls. We’re tremendously ignorant about what makes people tick.”

Johan (Scenes From a Marriage, 1973)

It is also with his production of Scenes From a Marriage that he became the first director to effectively make the leap from film to television while maintaining his artistic integrity, recognising the potential of the miniseries format. This is something he would repeat again in Face to Face and Fanny and Alexander, even though all three would also receive theatrical cuts for international distribution. Many of his other films frequently hover around the 90-minute mark, and so for this reason it is particularly impressive that he was so successful in creating long-form cinema too.

It is Persona that stands tall as the centrepiece of this period, marking Bergman’s greatest cinematic experiment in what many have described as the Mount Everest of film analysis. It is obscure in its formal patterns and rich in its crisp visual style, studying the human face like a filter through which emotions may be either honestly expressed or deceitfully masked. The blending of identities previously explored in Wild Strawberries and The Silence also reaches a pinnacle here, and it is fascinating to see how Bergman would continue to use this device to specifically get to the root of his female characters, as we later see in Cries and Whispers. Usually if he was going to feature music in his films, it would be existing classical pieces, but it is fitting that both this and Hour of the Wolf were the two films he chose to involve avant-garde composer Lars Johan Werle, emphasising their existential terror through a pair of dissonant, experimental scores.

There is another unofficial trilogy which forms too between Hour of the Wolf, Shame, and The Passion of Anna, considering a trio of couples with artistic inclinations lost in spiritual crises. Quite significantly, this is where Liv Ullmann started working with Bergman, acting besides Max von Sydow in all three films. Later she would also follow Bergman to Hollywood when he made The Serpent’s Egg, his second English-language film after The Touch. Neither are major artistic achievements, but still demonstrate his willingness to keep moving outside his comfort zone.

Finally, Bergman’s surrealism began to settle on a series of recognisable traits during these years. Silent sequences of characters wandering empty hotels, manors, apartments, and houses turn these spaces into dreamy limbos, located somewhere within their uneasy subconscious. The sounds of ticking clocks often accompany these scenes too, implying the imminence of death even in these apparently timeless realms. The first time we witness this device may have been in The Silence, but he continues to draw it through Cries and Whispers, Face to Face, and Fanny and Alexander too, uncovering the psychological root of his characters’ fears and desires.

Television Specials (1984 – 2003)

There are few filmmakers who have kept up as great a level of creative stamina across a large span of time as Ingmar Bergman, though in the last couple decades of his life even he began to grow tired, and the quality of his work declined. Despite Fanny and Alexander being intended as his last film before committing himself entirely to theatre, he did keep working on television projects. He had touched on this before in specials like From the Life of Marionettes, but from here it became his entire career. Unfortunately, most of these films have very little artistic merit, plainly revealing their limited budgets in their poor cinematography and uncharacteristically messy writing.

Two exceptions stand here. The first is After the Rehearsal, which is deeply in touch with Bergman’s love of theatre. Though he sets it entirely on a stage and thus compromises its cinematic power, his formal manipulations of time through dreams and flashbacks remain strong, slipping an ageing theatre director back through time to an old relationship.

The other exception is Saraband – the last film of Bergman’s entire career, and a fitting return to form. Though often described as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage, it is much more an observation of the imprint its aged divorcees have left on the younger generations now carrying their legacies. Bergman had contemplated the regrets of old age before, but this feels far more grounded in his firsthand experience than the surreal meditations of Wild Strawberries and Autumn Sonata, now finding peace in the act of introspective reminiscence and his longstanding adoration of classical music.

Many of his usual trademarks are present in Saraband, including savage dialogue viscerally thrown between wounded characters, but in the very final minutes there are no such acts of spiritual desecration to be found. With two of his greatest actors by his side, Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson, Bergman finally appreciates the pure bond between lovers, parents, children, and friends that transcends all other worldly distractions.

Four years later, Ingmar Bergman passed away in his sleep at his home on Fårö. The date was 30 July, 2007 – the same day as Michelangelo Antonioni’s passing. His influence as one of the all-time great directors and screenwriters continues to be felt in the work of virtually every filmmaker working today, from the severe aesthetic precision of Paweł Pawlikowski’s films Ida and Cold War, to Paul Schrader’s direct evocation of Winter Light in First Reformed.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1946 | It Rains on Our Love | R |

| 1947 | A Ship Bound for India | R |

| 1948 | Port of Call | R |

| 1949 | Thirst | R |

| 1950 | To Joy | R |

| 1951 | Summer Interlude | R/HR |

| 1953 | Summer with Monika | HR |

| 1953 | Sawdust and Tinsel | HR/MS |

| 1954 | A Lesson in Love | R |

| 1955 | Dreams | HR |

| 1955 | Smiles of a Summer Night | HR |

| 1957 | The Seventh Seal | MP |

| 1957 | Wild Strawberries | MS/MP |

| 1958 | The Magician | R/HR |

| 1960 | The Virgin Spring | MP |

| 1961 | Through a Glass Darkly | HR |

| 1963 | Winter Light | MP |

| 1963 | The Silence | MP |

| 1964 | All These Women | HR/MS |

| 1966 | Persona | MP |

| 1968 | Hour of the Wolf | MS |

| 1968 | Shame | MS |

| 1969 | The Passion of Anna | HR |

| 1971 | The Touch | R |

| 1972 | Cries and Whispers | MP |

| 1973 | Scenes from a Marriage | MS |

| 1976 | Face to Face | MS |

| 1977 | The Serpent’s Egg | R |

| 1978 | Autumn Sonata | MP |

| 1980 | From the Life of Marionettes | R |

| 1982 | Fanny and Alexander | MP |

| 1984 | After the Rehearsal | R |

| 2003 | Saraband | HR |

Simply, wow.

Glad you like the page!

Awesome work, if you can do a study this big then you nothing should be off-limits to you.

Thanks Harry, virtually every other director seems less daunting in comparison haha

Fantastic work, Declan! SceneByGreen is becoming a better website and resource with every post – you should be proud. And this study is remarkable. It’s nice to see a completed piece with your thoughts and rankings since we kinda studied him at the same time; I loved the journey and I’m sure you did, too. It’s funny to see what we disagree on, but ultimately I think we’re on the same page: Bergman is him!

Thanks Pedro! I look forward to building it out with more director studies and lists in the future. As austere as he is, Bergman was a lot of fun to study haha. He’s got a great sense of humour beneath all the heaviness.

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green