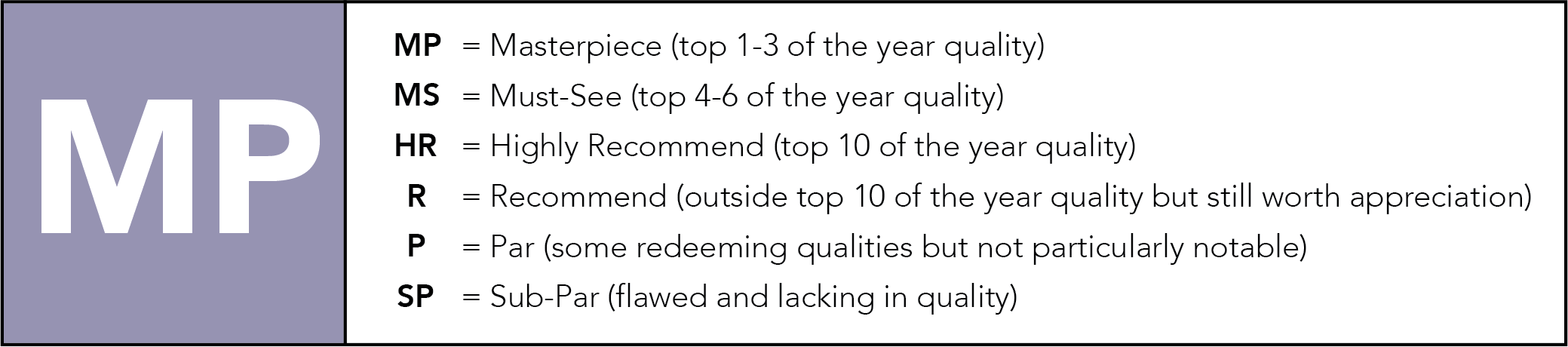

Mikhail Kalatozov | 1hr 37min

There is no known horror greater than that faced by soldiers on the frontlines of war, and as Veronika learns through the excruciating loss of her loved ones back home, there may be no loneliness like the grief suffered by its survivors. At least in the early morning of 22nd June 1941, the last few hours of her innocence are peacefully spent exploring Moscow and watching cranes fly overhead with her boyfriend Boris, only to be disrupted by the news of Germany’s invasion. He will surely be exempt from serving, she believes, yet he barely needs a push to offer up his services. Before she knows it, he is whisked away without so much as a farewell, and Veronika is left to make sense of this unfamiliar, upside-down world.

Life is incredibly fragile in The Cranes are Flying, but so too is the spirit of a nation subjected to unfathomable trauma, and Mikhail Kalatozov’s dynamic camerawork does not spare us from the immediacy of this anguish. Ultra wide-angle lenses are his primary aesthetic of choice here, delivering a crispness in close-ups which cross the boundaries of personal space, and in long shots reveal the sheer scale of Moscow’s overwhelming affliction. What was a once a city that Veronika wandered freely rapidly transforms into an urban dystopia of sandbags and anti-tank obstacles, imposing harsh, angular beams of steel on the environment and bouncing their jagged reflections off wet pavement.

High and low angles dramatically intensify scenes like these, and particularly when paired with a deep focus, they also draw attention to the raw, elemental textures of mud, water, and concrete that Kalatozov’s characters tread across. His rapid, handheld camera movements generate a visceral sense of whiplash here too, efficiently adjusting shots without ever sacrificing their severe clarity. Canted angles and delirious montages further disorientate us in Kalatozov’s hyper-stylised sequences, forcing us to adopt the mindset of those driven to the brink of madness and despair. When Boris is tragically shot in battle, long dissolves uneasily bridge spinning point-of-view shots and slow-motion dreams of marrying Veronika, while her own attempted suicide later adopts a similarly kinetic frenzy.

Kalatazov is wise to hold off on these more turbulent visuals until later in the film though, instead approaching Veronika’s first major loss with brisk tracking shots as she anxiously runs through smoke, debris, and emergency workers to reach her bombed-out apartment building. The edifice is still on fire when she climbs its crumbling stairs, and the reveal of her home reduced to nothing but rubble and open-air is devastating. All at once, a future without her family suddenly comes into focus, and she is sent reeling into a state of numbing shock.

Within the icon of ravaged innocence that is Veronika, The Cranes Are Flying places the soul of the Russian people, and actress Tatyana Samoylova plays each beat with understated sensitivity. Kalatozov is not quite a realist when it comes to cinematic style, though his penchant for capturing faces in intimate detail still allows for more naturalistic performances, giving the impression of an ordinary world falling prey to man’s corrosive madness.

Nowhere is this more evident either than in Veronika’s rape at the hands of Boris’ cousin Mark, set against the backdrop of a violent storm of lightning, billowing drapes, and a crashing sound design. The visual direction here verges on expressionistic, lifting our heroine far outside her comfort zone and inevitably isolating her even further, as she is forced to marry the man who has effectively stolen what little of herself she has left. Meanwhile, her forced relocation to a cramped cabin in Siberia with Boris’ disapproving family severs her last remaining link to the simple life she once knew back in Moscow, leaving her agonisingly unaware of whether her true sweetheart is even alive.

Still, somehow within all this fear and guilt, there remains salvation in a future that reveres the past. It is surely more than just coincidence which lands an orphan auspiciously named Boris in Veronika’s path when she is at her lowest, pushing her to make the first step towards rebuilding the family she lost. Neither is Kalatozov so cruel as to let her dwell in broken-hearted misery when she finally learns of her boyfriend’s tragic fate. As returning troops disembark trains and greet their families, his camera hangs steady on her teary face moving through the joyful yet suffocating crowd, striking a jarring contrast that feels almost unfair to Boris’ memory. As his friend Stepan takes the podium though, his words deliver a rousing assurance that the legacies of the fallen will become the foundation of a new promise – that no one will ever have to feel this pain again.

“We shall do everything to ensure that sweethearts will never again be parted, that mothers may never again fear for their children’s lives, that our brave fathers may not secretly hold back their tears. We are victorious and live on, not in the name of destruction, but in the name of building a new life!”

Veronika’s wounds may not be healed, but we can see this peace fill her up from within as the camera gently eases off its close-up. As she hands out the flowers she had brought for Boris, her eyes are directed upwards, and there Kalatozov recalls the innocence from the film’s opening scene that we had assumed was irrecoverable. Flying over Moscow in a v-formation, another flock of cranes heralds a new era for the Soviet Union. Maybe not an era for Boris, or even for Veronika who will never be the same as she was before, but one which will see both give to younger generations the blissful, idyllic lives that the horrors and tragedies of war have stolen from them.

The Cranes Are Flying is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.