Zach Cregger | 2hr 8min

When seventeen children from a single third-grade class rise from bed at 2.17am, walk out their front doors, and run into the night with their arms outstretched, we feel as if we are witnessing something deeply primordial unfold. George Harrison’s sombre, mellow vocals accompany the montage, cautioning the town to ‘Beware the Darkness’ – and indeed, this is only the beginning of the trauma soon to be inflicted on this fragmented community. The child’s eerie narration which recounts these events even frames it as a twisted fairy tale, albeit one that it claims to be a “true story,” daring us to accept the reality that no grieving parent ever wants to confront.

Following on from his debut Barbarian, Zach Cregger is once again exposing the horrors hidden beneath America’s suburban façade in Weapons, though this time ambitiously branching his narrative out further than before. Its structure is a shattered mirror, split into six pieces which reflect the perspectives of different individuals – the bewildered teacher, the bereaved parent, the unassuming principal, the feckless police officer, the homeless witness, and the single, surviving child from the decimated class. Each segment offers answers to questions raised in others, though due to their non-linear arrangement, it is the act of piecing them together which reveals the full scope of this collective nightmare. Unlike so many other contemporary horror films, Weapons cannot be pinned down to a straightforward allegory, instead building its formal strength upon the ingenuity of its disquieting, fractured storytelling.

With that said, there is a thematic undercurrent of addiction which runs strong through multiple characters here, beginning with the teacher whose entire class almost entirely disappeared overnight – Justine. The anguish of losing these children is only compounded by the scrutiny of a town desperate for a scapegoat, driving her back to the familiar refuge of liquor stores and bars. Her ex-boyfriend Paul suffers from similar vices, while wandering vagrant James seems wholly dedicated in his mission to score meth, and even the junk food that decorates Principal Marcus’ home subtly underscores his surrender to unhealthy habits. Of them all though, it is Archer who is most passionately dedicated to his obsession, consumed by grief and zealously seeking answers to his son’s disappearance.

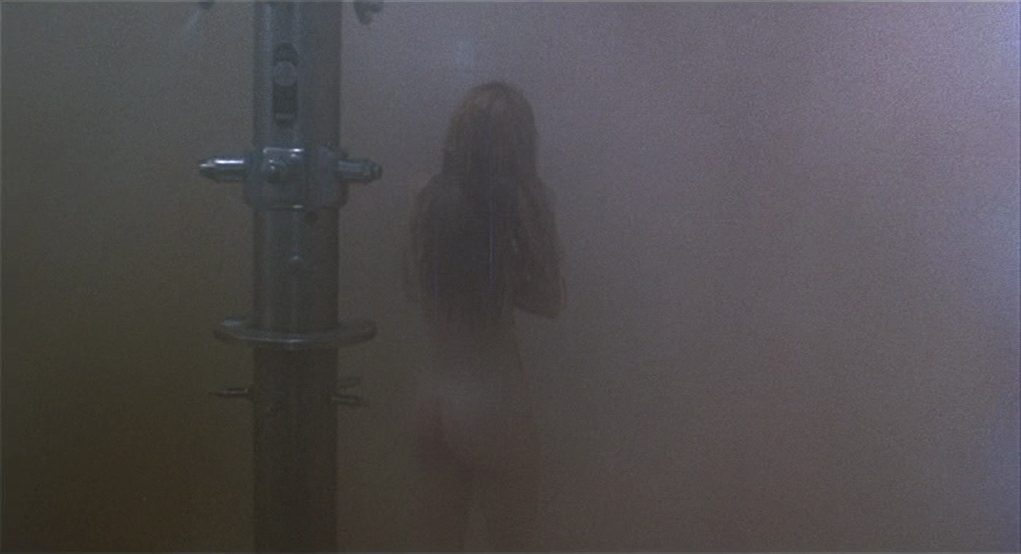

Justine’s lesson on parasites and the documentary that Marcus watches about mind-controlling fungi serve as eerie foreshadowing here, echoing the underlying fear which runs deep in Weapons – total loss of physical and psychological control. Cregger deftly teases out the terror which lurks within the home of the class’s only survivor, Alex, only gradually revealing its domestic decay to be a manifestation of addiction’s corrosive grip. Though no fault lies with his immediate family, it is as if a spirit has drained this house of all joy and love, rendering its occupants empty vessels of their former selves.

Of course, the truth of the danger lies even deeper than Alex initially comprehends, and Cregger relishes unravelling it with a slow, suffocating dread. At some point during each of our six lead characters’ segments, he invariably hangs his camera on the back of their heads, attaching us to their overwhelmed psyches through steady, prolonged tracking shots. Formally, this device is also an extension of the subjectivity woven into the very narrative, matching its haunting mosaic of intersecting perspectives.

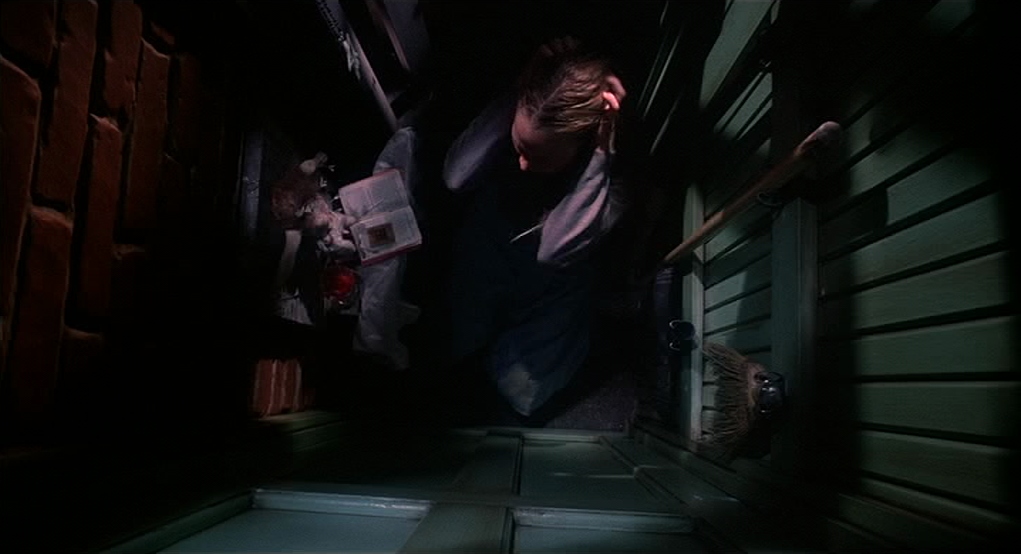

If there is any weakness to Weapons’ structure, then it lies in the digressions of some later chapters, swerving away from the single point-of-view conceit to revisit previously established characters. Nevertheless, it is a minor detail that Cregger efficiently smooths over with his parallel editing, and the emotional continuity carried by Julia Garner’s highly-strung presence certainly helps too. If any single performance takes the spotlight here, it is her portrayal of a deeply flawed schoolteacher, known for frequently overstepping boundaries with children yet unable to resist her own maternal instincts.

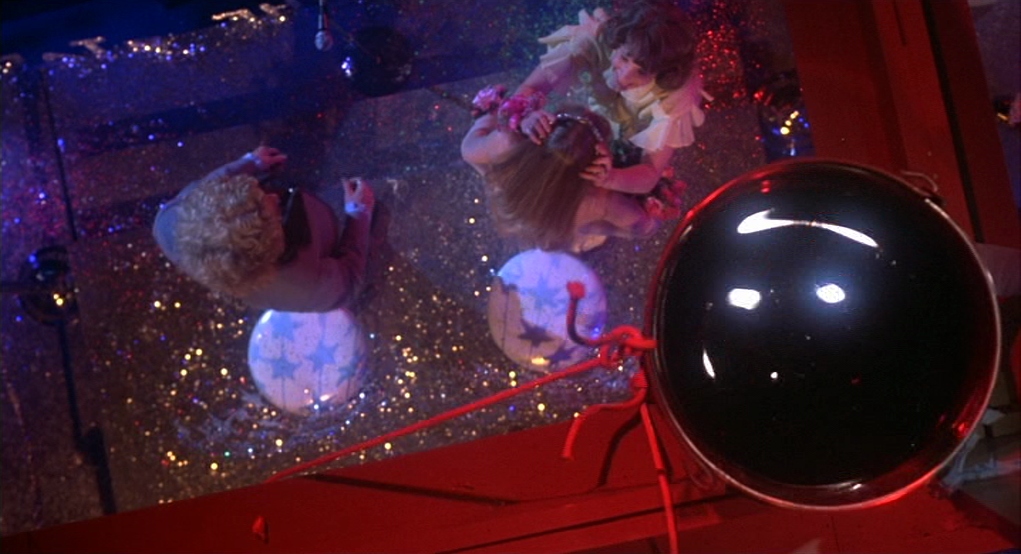

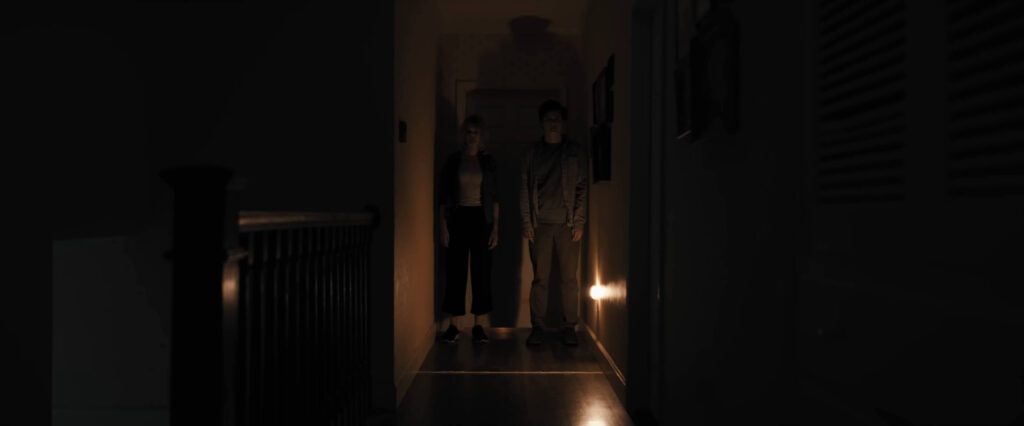

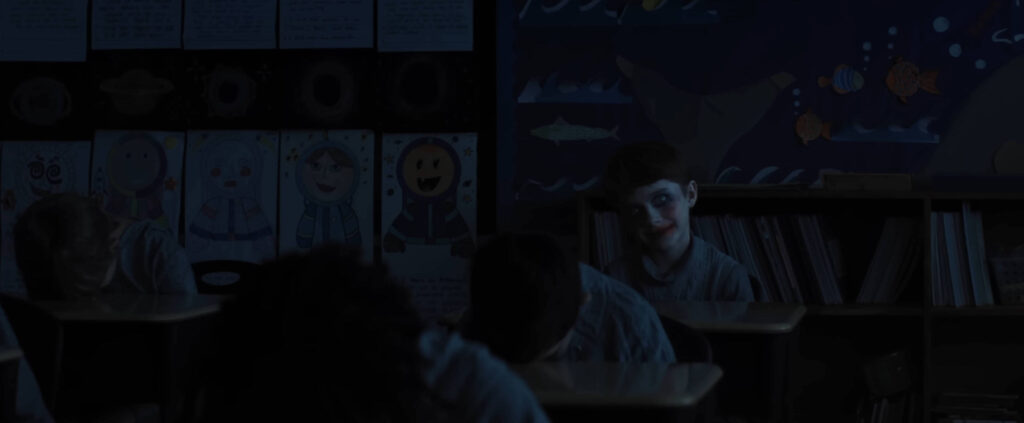

In terms of pure horror, Cregger’s splintered storytelling effectively heightens the element of the unknown too through chilling, elongated suspense. Although Justine investigates Alex’s house and finds two motionless silhouettes inside, it isn’t until James’ segment that we see their faces, and only once we reach Alex’s do we learn who they are. Similarly, visions of faces painted in clown makeup haunt the dreams of multiple characters, casting a chilling omen that finally comes into focus with the arrival of Alex’s flamboyant Aunt Gladys. Her bright orange wig, oversized glasses, and smeared lipstick might almost be mistaken for a drag queen’s getup if she did not project such a sinister aura, suggesting a far more malevolent force hiding beneath that mask of camp eccentricity.

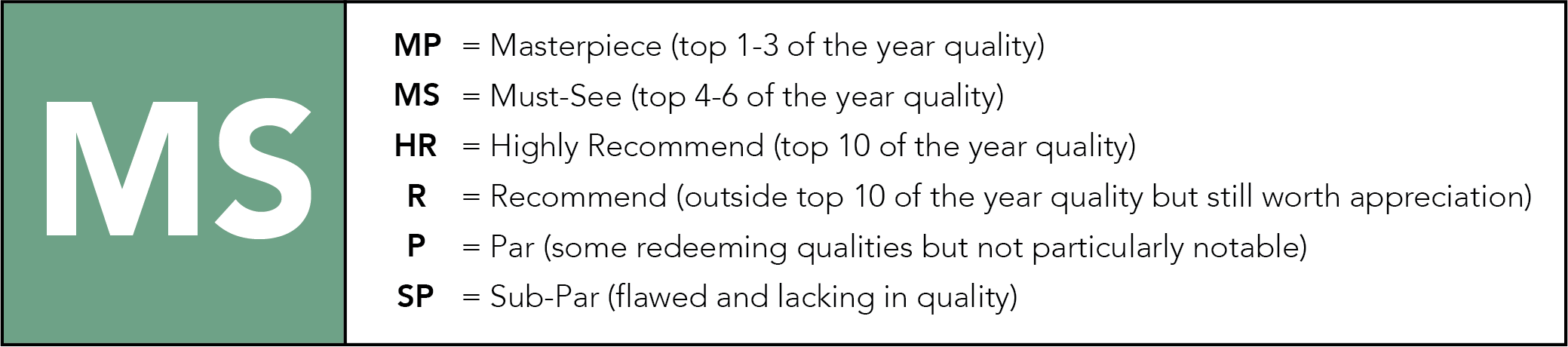

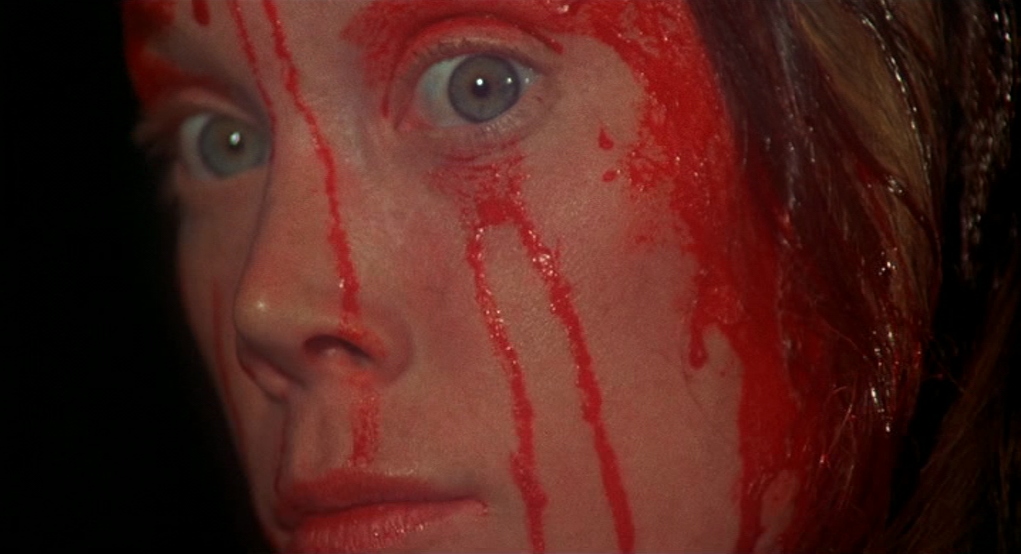

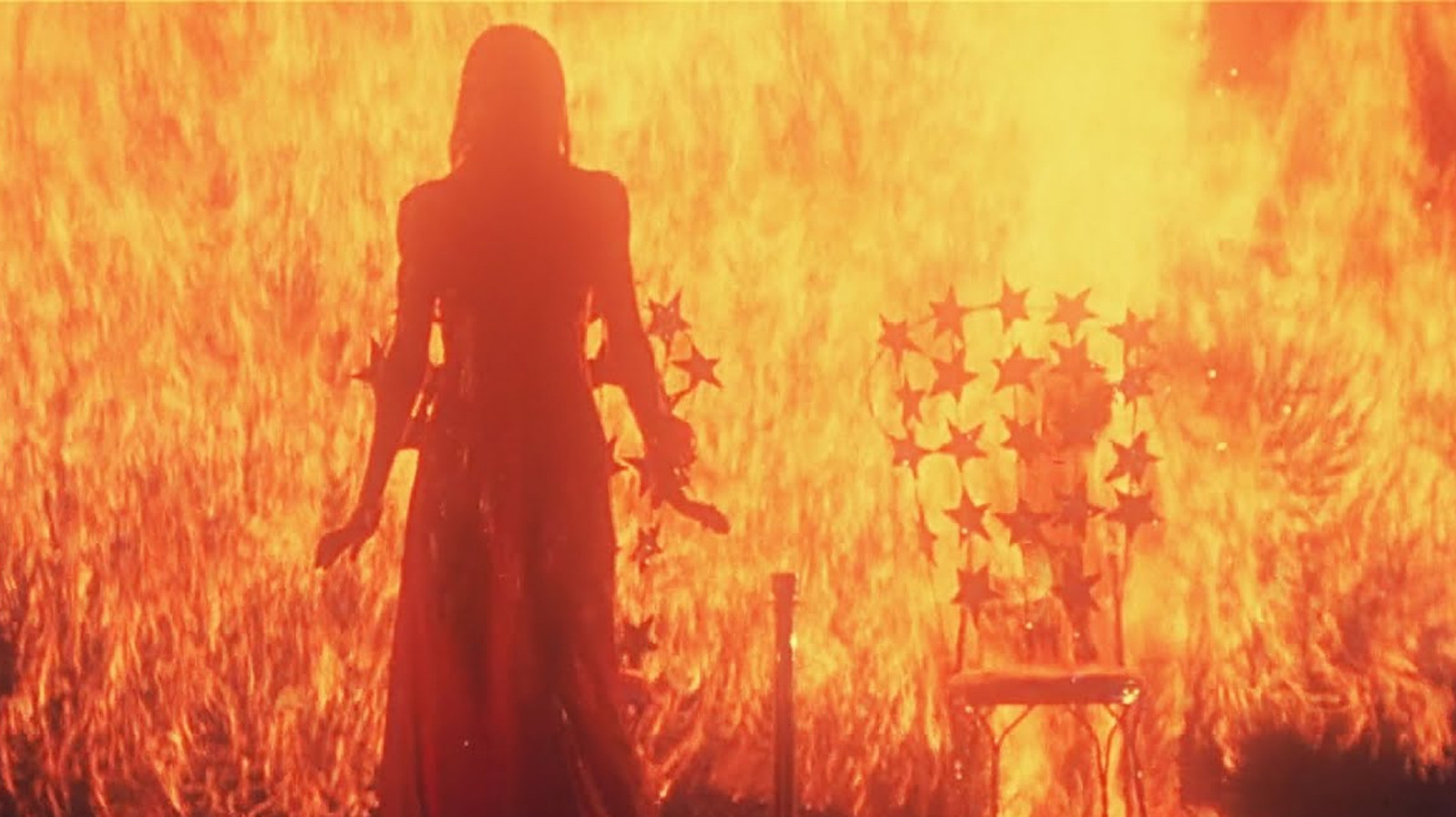

This is a film of searing, unshakable images after all, not so easily forgotten thanks to their uncanny distortion of the familiar. There is no soul behind the bulging eyes of one possessed victim, their mouth black with vomit and face grotesquely bloodied, nor is there any humanity in the jerky movements of a woman staggering through the darkness towards an unconscious target. Cregger knows when to hold a shot, and it is especially in that latter scene where the lingering camera draws the tension to a breaking point, refusing to reveal who or what this figure is shambling towards us.

Perhaps most frustrating of all is the helplessness of these adults in addressing the local catastrophe. We are consistently led to place our trust in authority figures, yet each time we are let down, watching them fall prey to an unfathomable force not even they can grasp. As such, Weapons is also lightly imbued with the spectre of a school shooting metaphor, seeing parents desperately try and fail to rationalise the inexplicable destruction of innocence – yet this explanation alone does not capture the complete, psychological disorientation that saturates the film. Even when the peril is finally driven into the light and comically mocked, the lifelong trauma remains, reminding the community of their existential fragility. Grief is a corrosive, all-consuming affliction after all, and Cregger renders its sprawling impact with sinister precision in Weapons, hollowing out a forsaken town suspended between denial and dread.

Weapons is currently playing in cinemas.