Jean Vigo| 1hr 29min

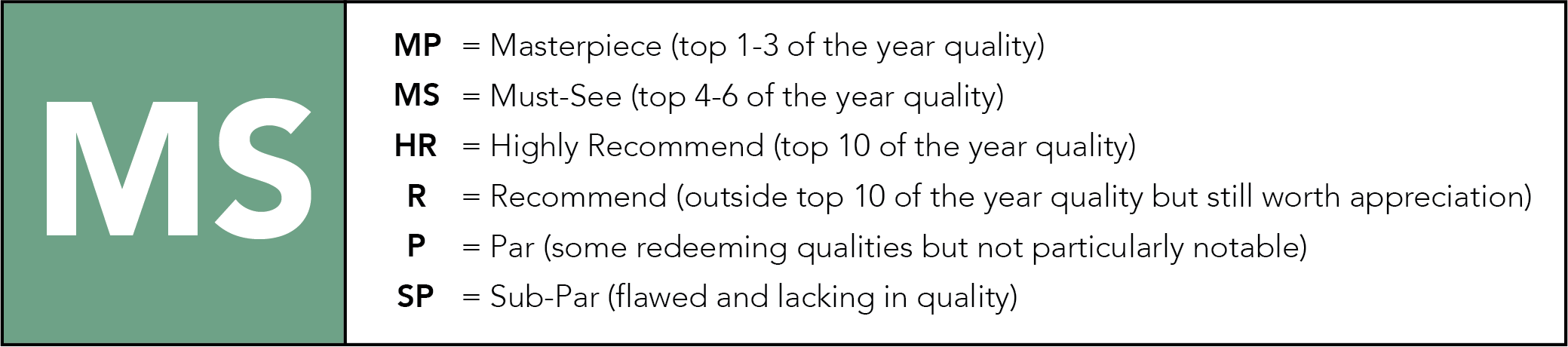

Life aboard Jean’s canal barge L’Atalante is not quite the romantic escape that his young bride Juliette dreamed it would be. The men who sail it up and down the Seine are clearly unaccustomed to female company – particularly the eccentric first mate Père Jules, whose horde of cats, hand-drawn tattoos, and uncouth mannerisms clash with her more refined sensibilities. She appears truly alone as the camera follows her in a tracking shot across the entire span of the ship, and there is barely room for privacy in the clutter of Jean Vigo’s interiors, as bottles, lamps, and tools crowd out every frame. His trademark high angles not only serve a practical purpose fitting multiple characters into the same shot, but from this vantage point, we also grasp the suffocating claustrophobia of Juliette’s new home

None of this is to suggest that the barge is an irredeemable prison though. L’Atalante is a fable of ruptured innocence, jealousy, and temptation, tugging at the seams of Jean and Juliette’s fragile relationship while illuminating a path to the marital bliss that has eluded them. Salvation does not lie in the city’s worldly flights of fancy, as alluring as they may be, but aboard that very boat which she longs to leave behind. For Jean as well, contentment is only found once the chains of insecurity and mistrust are shed, guiding him towards an appreciation of the woman he has married. Although this ship may feel like an oppressive enclosure at times, Vigo’s lyrical direction also reveals it to be a sanctuary of healing, freely drifting from port to port with no anchors to tether it down.

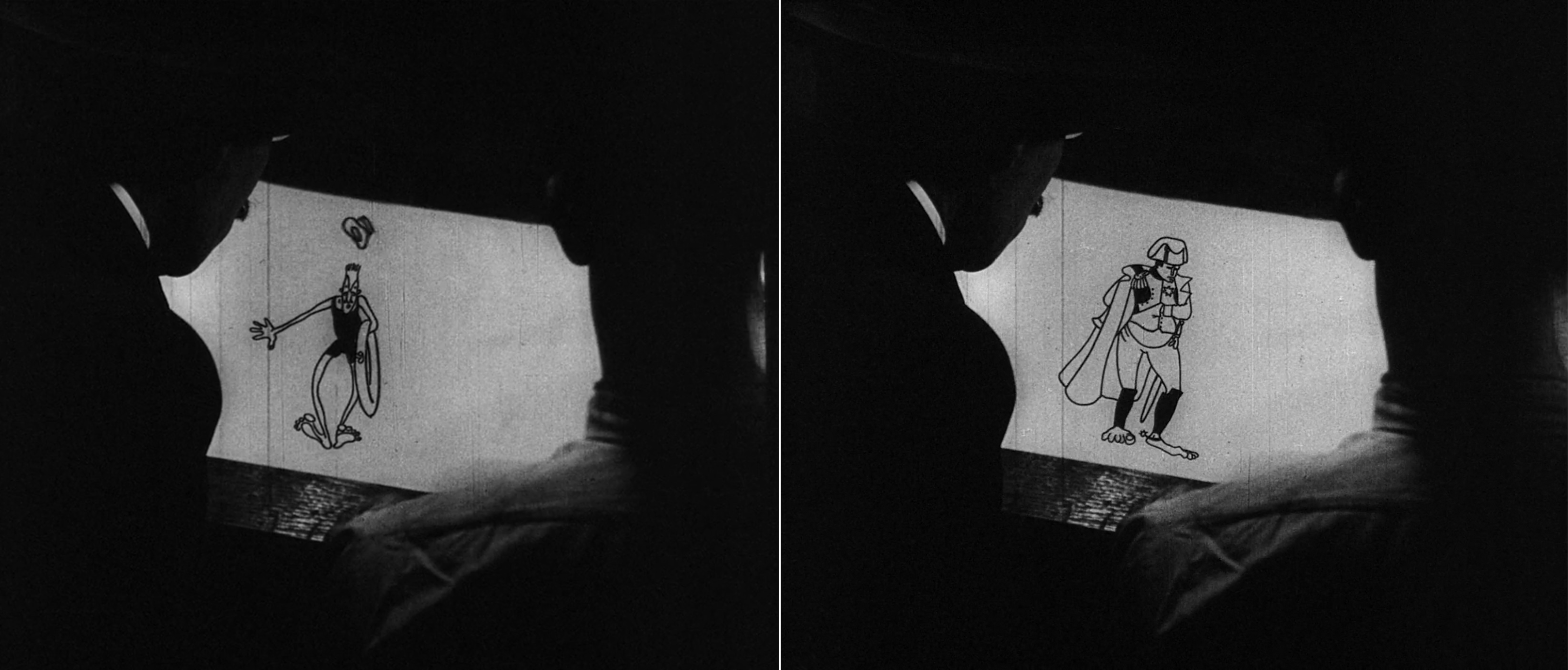

Quite ironically, the character that L’Atalante affords the most personable qualities is Jules, who transcends mere comic relief and becomes Juliette’s closest friend aboard the boat. As subtly expressive as Dita Parlo’s performance may be, Michel Simon outshines both leads here, fully realising the endearing humanity in Jules’ idiosyncrasies. This is a man who joyfully dances around in a skirt that Juliette has sewn, and later on falls victim to a prank when he is astounded by his apparent ability to produce music by tracing a vinyl record, only for Vigo to reveal the cabin boy playing his accordion from the other side of the room. In his own time, Jules is also a collector of souvenirs from his travels across the world, ranging from a jar of grotesque, pickled hands to a mechanical puppet which conducts an imaginary orchestra. Wherever the camera sits in this wondrous cabin of curiosities, ornaments frequently obstruct our view, reframing what initially seemed to be a hoarder’s palace into a museum of exotic tales and warm conversation.

Not that Jean is particularly happy about the hospitality which Juliette finds in his first mate’s quarters. It doesn’t take long after getting married for his envy to spike, smashing up Jules’ cabin upon catching them together, and glowering at flirtatious strangers when they journey into Paris. The camera glides with them into a dance hall where a handsome street peddler entertains Juliette with magic tricks, a song, and a dance, and even after Jean pushes him to the floor, he persistently seeks to lure her deeper into the city.

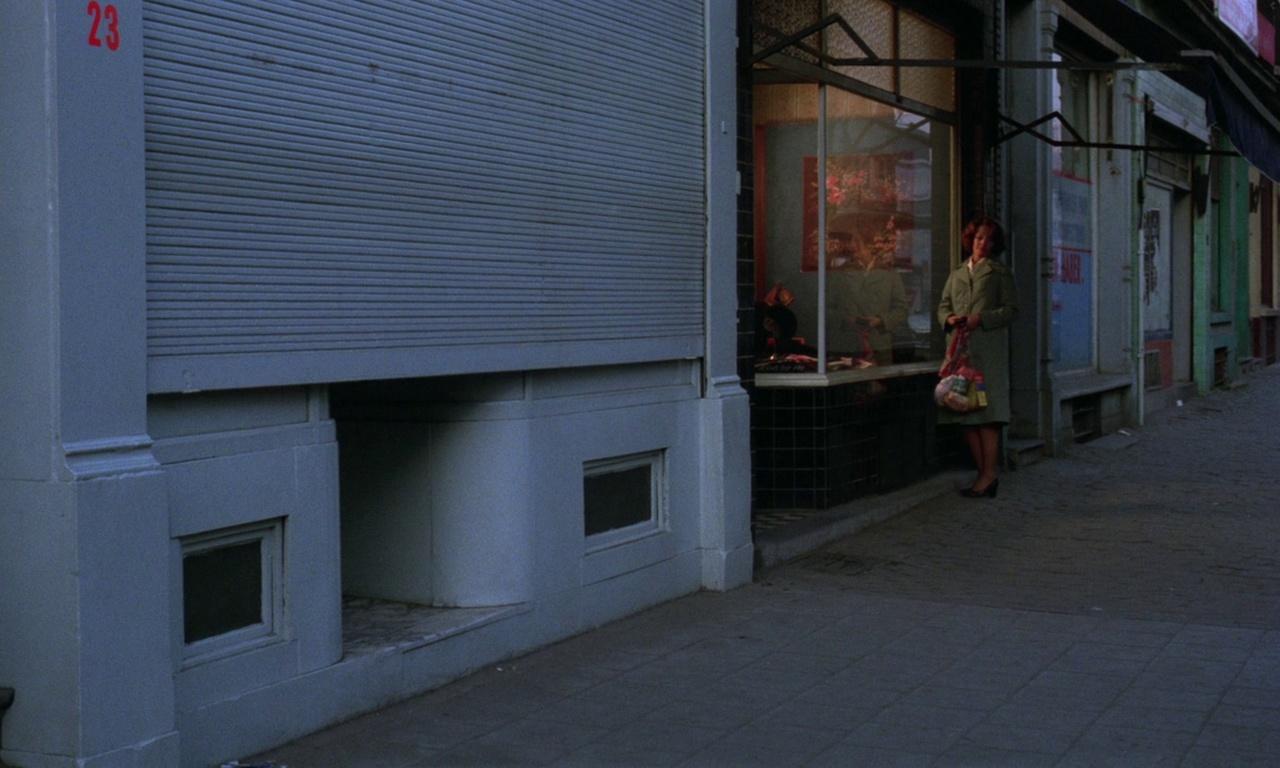

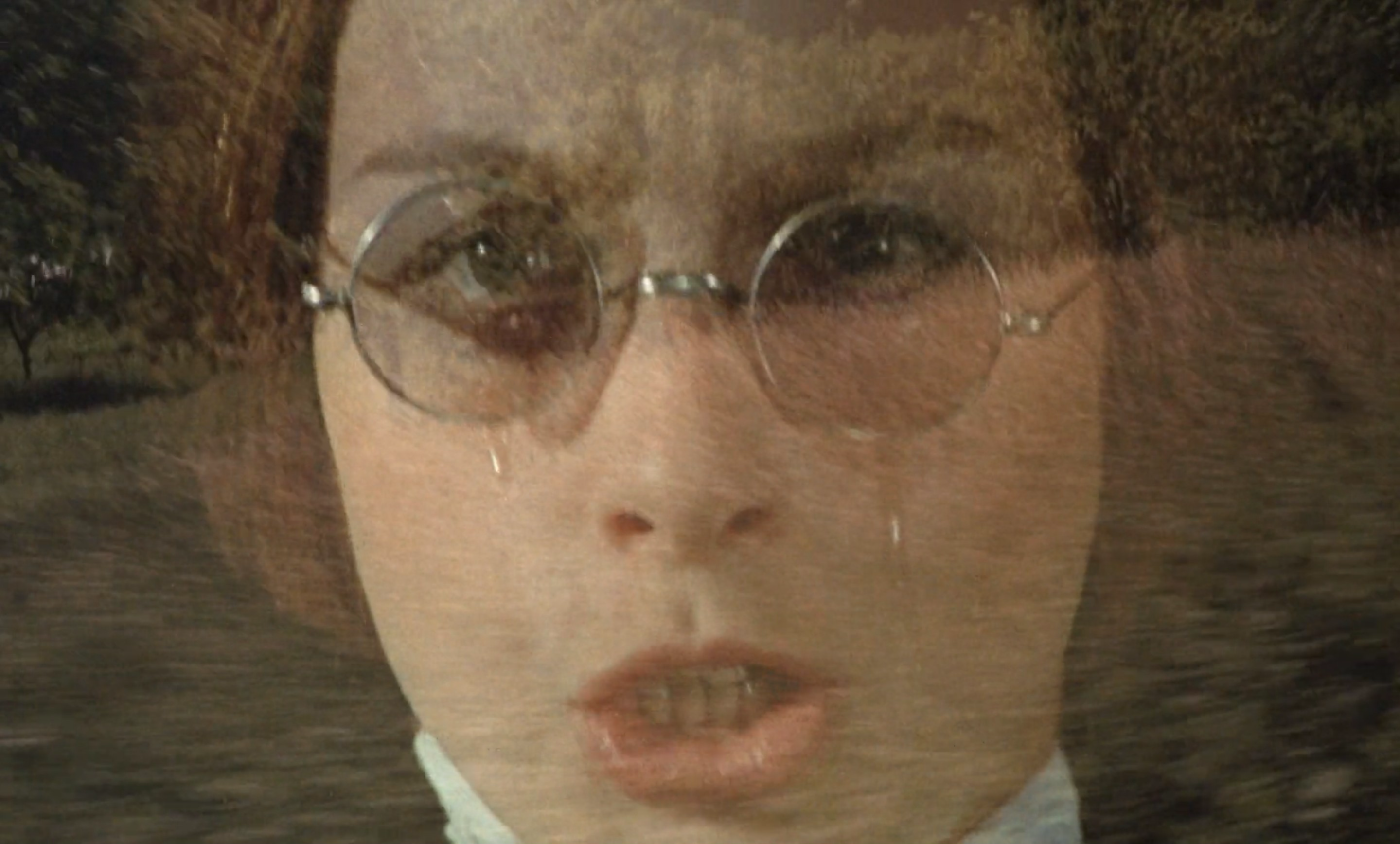

And lured she is – just as Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans portrayed the city as a metropolis of excitement and danger a few years earlier, so too does L’Atalante tantalise Juliette with its urban thrills. Vigo’s location shooting thrives along the Seine’s industrial ports, setting his drama against warehouses, chimneys, and steam trains, while her journey into the shopping district of live bands and window displays carries a vibrant energy that her husband’s boat lacks. Still, the exhilaration can only last so long. Having been left behind, she tries to buy a train fare to reach Jean’s next stop in Le Havre, yet the dark reality of Paris is alarmingly revealed when a thief steals her purse and she is forced to find work.

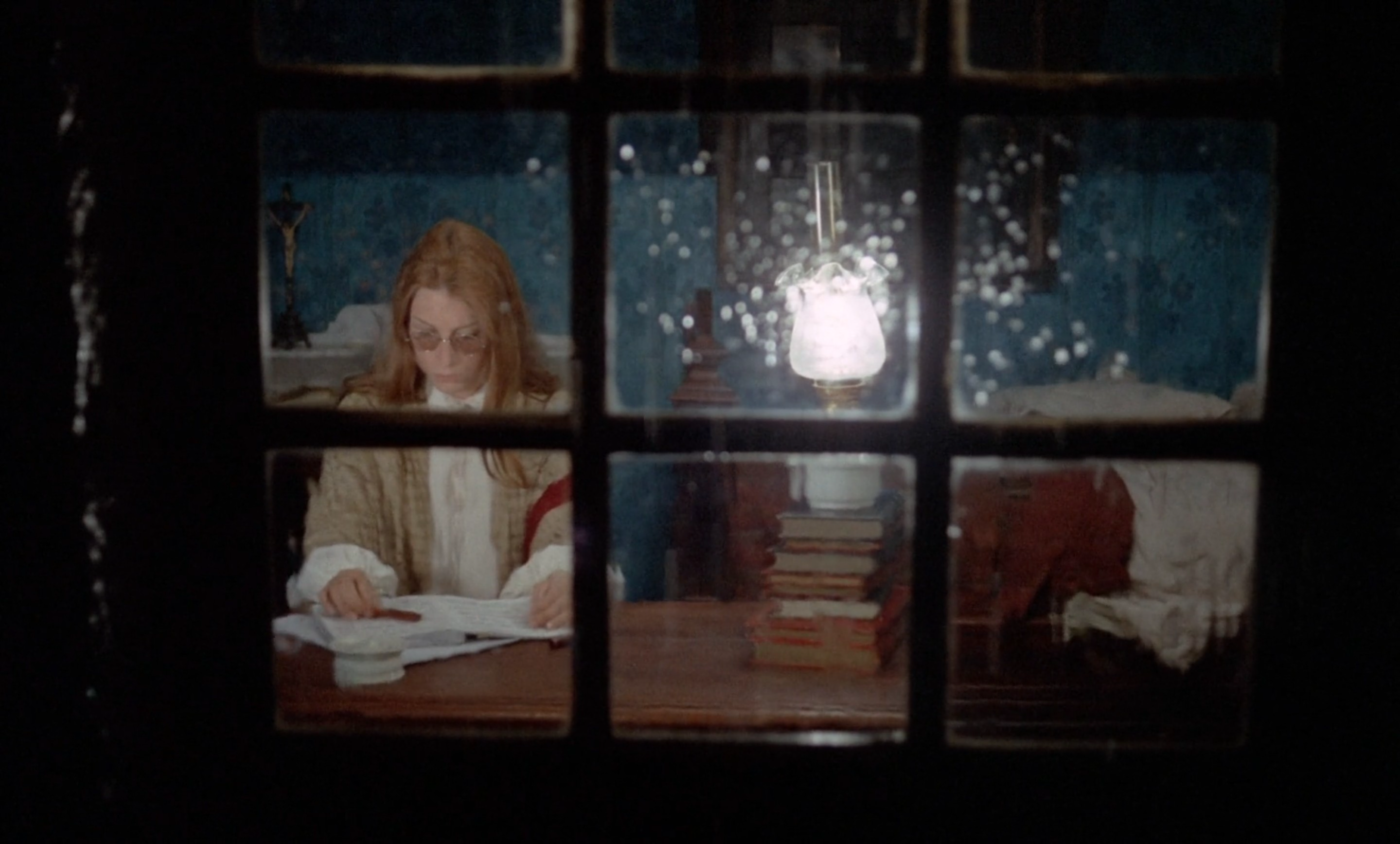

It doesn’t take long for regret to strike her jealous husband either, driving him into a deep depression. Wholeheartedly believing the myth that it is possible to glimpse the face of one’s lover in water, Jean impulsively dives overboard, and Vigo capitalises on the opportunity to sink us into his aching, dreamy mind through surreal dissolves and double exposure effects. There in the depths of the Seine, she floats like a doll suspended in the currents, and a light breeze ruffles her blonde hair as she lets out a silent laugh. Trying to cheer up his skipper, Jules plays a romantic melody on his phonograph, which Vigo further uses to underscore a montage intercutting their yearning search for each other. More long dissolves bridge match cuts between their restless tossing and turning, unable to get a good night’s sleep in each other’s absence, before finally ending this astounding sequence with a dishevelled Jean facing up to his displeased company manager.

Perhaps it is fate that ultimately draws friends and lovers together after their lonely parallel journeys, or maybe love really is that powerful a force in L’Atalante that it echoes across canals, calling them back home. After all, ‘The Bargeman’s Song’ not only provides comfort to Juliette during her visit to a music booth, evoking memories of her days with men who regularly sung this familiar tune on the boat. It also draws the attention of Jules, who happens to be passing by at the exact moment the melody is playing through a speaker on the street. In Juliette and Jean’s embrace, past misgivings are finally forgiven, rapidly dissolving all heartache. At last, their tiny vessel becomes a home where love takes root once more, and quiet freedom is found in its gentle, unanchored drift.

L’Atalante is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.