-

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Through his indisputable talent as an avant-garde storyteller, Kubrick accomplishes a formal rigour and aesthetic precision in 2001: A Space Odyssey that so few artists have ever come close to, revealing a glimpse of humanity’s infinite potential through a staggering feat of filmmaking that measures up to the transcendent, cosmic scale it is representing.

-

Cries and Whispers (1972)

Ingmar Bergman’s wrestling with matters of faith and tortured female relationships has never been so vividly illustrated as it is in Cries and Whispers, confining its three sisters and their maid to the crimson-saturated dreams of their family home, and surreally interrogating the fractures which only deepen with their parallel suffering.

-

Throne of Blood (1957)

Akira Kurosawa’s landscapes of ambition, fate, and consequences make for a perfect marriage with Shakespeare’s Macbeth in Throne of Blood, formally integrating the narrative’s treacherous power plays with historical elements of Japanese Noh theatre, and mounting the forces of nature and destiny against the dishonourable samurai at its centre.

-

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002)

Violent retribution is not a solution in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, but an endless chain of wounded victims seeking mutually assured destruction, delineated with cool precision in Park Chan-wook’s murky green palette, measured pacing, and formal mirroring of two parallel men on futile quests for justice.

-

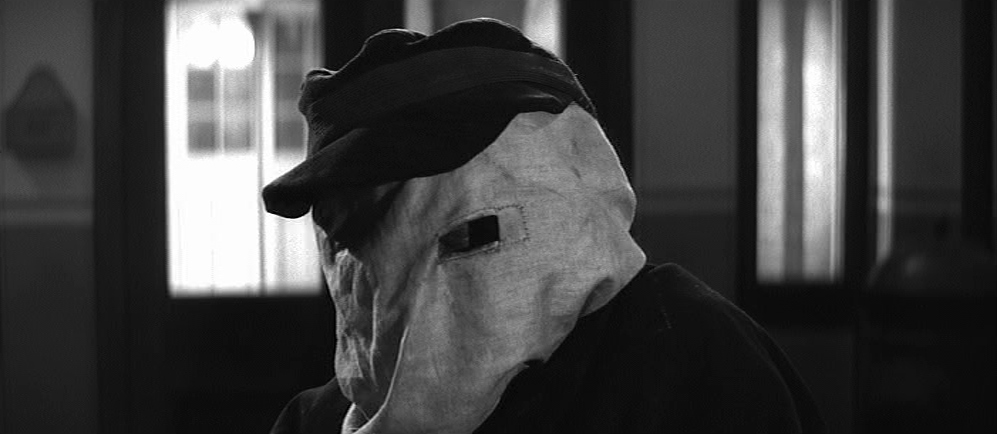

The Elephant Man (1980)

At first glance, The Elephant Man does not hold to David Lynch’s usual trademark of dreamlike narrative structures, and yet a dark thread of surrealism nevertheless emerges in this gorgeously photographed biopic of the severely deformed John Merrick, locating the true key to his dignified self-acceptance through the hypnotic landscape of his own mind.

-

The Touch (1971)

The Touch may be one of Ingmar Bergman’s plainer stylistic efforts, but his wielding of theological symbolism to interrogate a broken love triangle is deft, bitterly driving the Madonna’s degraded image and a tainted Garden of Eden between his doomed lovers.

-

Notorious (1946)

There is remarkable dramatic tension in Notorious’ thickly plotted conflict of romance and thriller conventions that tugs a pair of post-war spies between deep passion and cold pragmatism, but through his motifs of seemingly innocuous refreshments Alfred Hitchcock also develops an even more intricate formal structure, containing darker secrets within them than one might expect.

-

Eraserhead (1977)

Within Eraserhead’s nightmares of mutant babies and urban isolation, it is the psychological impression of its surreal imagery which carries far more impact than any attempts to derive its literal meaning, as David Lynch mystifyingly manifests the dark subconscious of one young father existentially terrified of parenthood.

-

Ran (1985)

For all of Akira Kurosawa’s jaw-dropping historical battles staged with colourful splendour and imposing characters that fill out Ran’s immense narrative, at its core is a seething bitterness towards humanity’s existential isolation, propelling the dramatic power struggles between three jealous brothers in feudal Japan.

-

The Passion of Anna (1969)

Ingmar Bergman’s personal turmoil during production of The Passion of Anna infuses this chamber drama with a shaggy, improvisational quality, deconstructing its titular widow’s grief with the same imperfect honesty which he himself is guilty of, and bringing a raw vulnerability to complex characters straining against each other’s cruelty.

-

Videodrome (1983)

David Cronenberg’s blending of intellectual musings on modern mass media with grotesque body horror makes Videodrome’s dire warnings all the more visceral, robbing brainwashed individuals of their humanity by fusing them with the technology they have become reliant on, and marking a triumphant success in transgressive genre filmmaking for the young auteur.

-

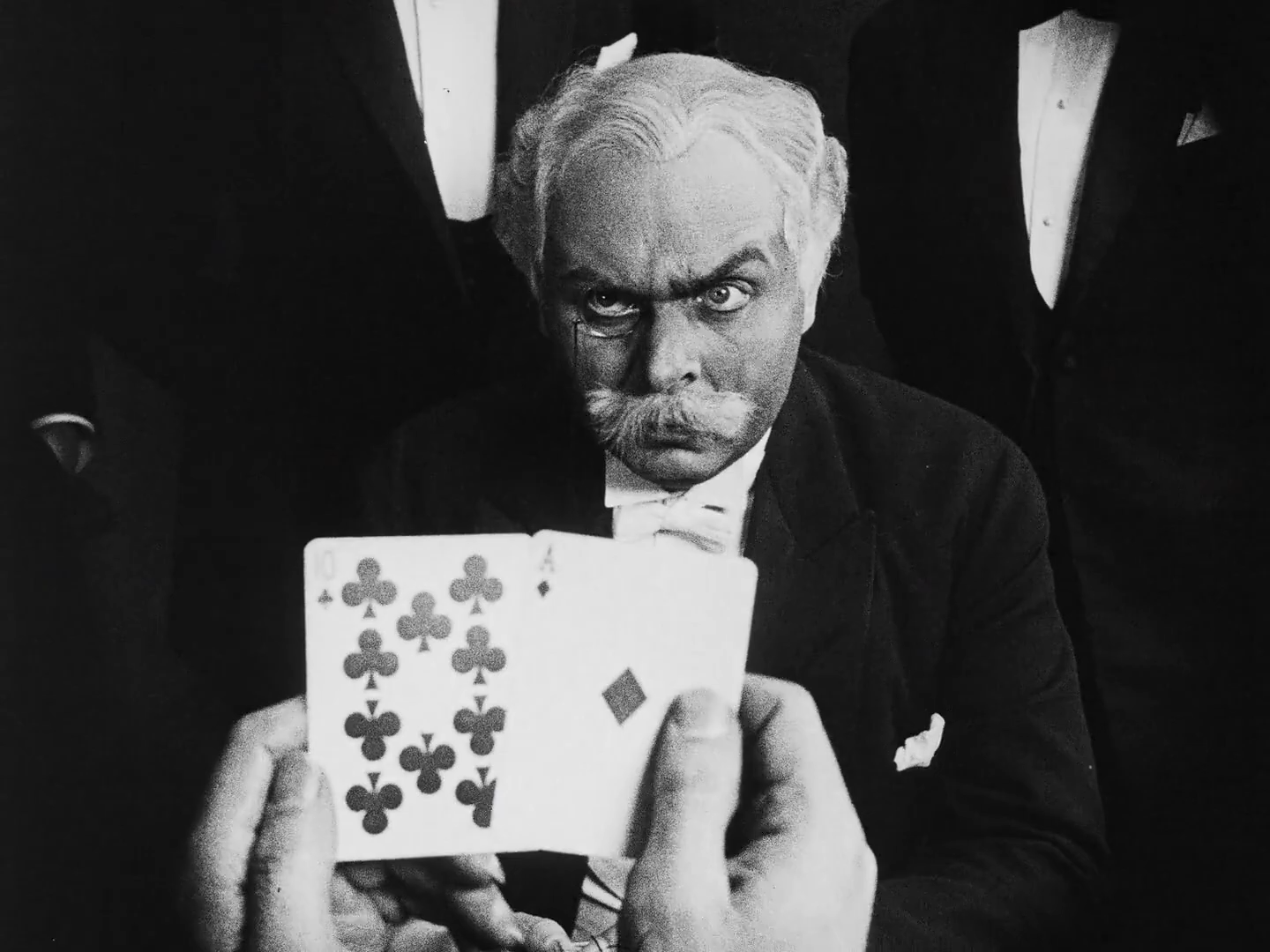

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922)

Fritz Lang distils the fearful mistrust of authority in Weimar Germany down to a single criminal mastermind in Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, painting out an expressionistic world under his hypnotic control with dark, jagged strokes, and setting the proto-noir standard of elaborately plotted crime narratives.